Ayrton crossed the deck with a sure step

Ayrton crossed the deck with a sure step

Ayrton appeared. He crossed the deck with a sure step and climbed the stairs to the quarterdeck. His eyes were dark, his teeth clenched, his fists closed convulsively. His demeanour was neither boastful nor humble. When he came into the presence of Lord Glenarvan, he folded his arms, mute and calm, waiting to be questioned.

“Ayrton,” said Glenarvan. “Here we are, you and us, on the Duncan you wanted to deliver to Ben Joyce’s convicts!”

At these words, the quartermaster’s lips trembled slightly. A quick flush coloured his impassive features. Not the redness of remorse, but the shame of failure. On this yacht, which he had planned to command as its master, he was a prisoner, and his fate would be decided in a few moments.

However, he did not answer. Glenarvan waited patiently, but Ayrton persisted in keeping an absolute silence.

“Speak, Ayrton. What do you have to say?” asked Glenarvan.

Ayrton hesitated; the creases of his brow furrowed deeply. Eventually, he spoke in a calm voice. “I have nothing to say, My Lord. I was foolish enough to let myself be captured. Act as you please.”

His answer given, the quartermaster turned his gaze to the coast to the south,1 and he affected a profound indifference to everything that was going on around him. To look at him, you would think that he was a stranger to this serious affair. But Glenarvan had resolved to remain patient. He had a strong desire to know some of the details of Ayrton’s mysterious past, especially his connection with Harry Grant and the Britannia. He resumed his interrogation, speaking with extreme gentleness, and imposing the most complete calm over the violent irritation of his heart.

“I think, Ayrton, that you will not refuse to answer some of the questions I want to ask you,” he said. “But first, should I call you Ayrton or Ben Joyce? Yes or no, are you the quartermaster of the Britannia?”

Ayrton remained impassive, watching the coast, deaf to any questions.

Glenarvan, his eyes flashing, continued to question the quartermaster.

“Will you tell me how you left the Britannia? Why were you in Australia?”

The same silence; the same imperturbability.

“Listen to me, Ayrton,” said Glenarvan. “It’s better for you if you talk. You should be aware that frankness is your last recourse. For the last time, do you want to answer my questions?”

Ayrton turned his head to Glenarvan and looked him in the eyes “My Lord, I do not have to answer. It is up to justice, and not to me, to provide evidence against me.”

“The proofs will be easy!” said Glenarvan.

“Easy, My Lord?” said Ayrton mockingly. “It seems to me that Your Honour is a great deal ahead of himself. Me, I affirm that the best judge at the bar would be embarrassed to have me before him! Who can say how I came to Australia, since Captain Grant is no longer here to tell it? Who will prove that I am this Ben Joyce sought by the police, since the police have never held me in their hands, and my companions are at liberty? Who, except you, will report a single crime or blameworthy action against me? Who can say that I wanted to seize this ship and deliver it to the convicts? Nobody, hear me. Nobody! You have suspicions, true, but you need certainty to convict a man, and you have no certainties. Until proven otherwise, I am Ayrton, quartermaster of Britannia.”

Ayrton stopped talking, and he soon returned to his previous indifference. He no doubt imagined that his statement would terminate the interrogation, but Glenarvan spoke again.

“Ayrton, I am not a prosecutor charged with indicting you. It’s not my business. It is important that our respective positions are clearly defined. I’m not asking you for anything that could compromise you. That’s the concern of justice. But you know the search that I’m pursuing, and with a word you can put me back on the trail I lost. Do you want to talk?”

Ayrton shook his head like a man determined to remain silent.

“Will you tell me where Captain Grant is?” asked Glenarvan.

“No, My Lord,” said Ayrton.

“Will you tell me where the Britannia ran aground?”

“Nothing more.”

“Ayrton,” said Glenarvan, almost imploringly, “will you at least, if you know where Harry Grant is, tell his poor children, who are just waiting for a word from your mouth?”

Ayrton hesitated. His features contracted, but in a low voice he murmured “I can not, My Lord.” And he added violently, as if he had reproached himself for a moment of weakness “No! I will not talk! Hang me if you want!”

“Hang!” exclaimed Glenarvan, overcome by a sudden flash of anger. Then, mastering himself, he continued in a low voice. “Ayrton, there are neither judges nor executioners here. At the first port of call, you will be handed over to the English authorities.”

“That’s all I ask!” said the quartermaster.

He returned quietly to the cabin which served as his prison, and two sailors were placed at his door with orders to watch his slightest movements. The witnesses of this scene retired, indignant and desperate.

Since Glenarvan had just failed against Ayrton’s obstinacy, what was left for him to do? Obviously to continue the plan formed at Eden to return to Europe, even if to resume this unsuccessful enterprise later, because the traces of the Britannia seemed to be irrevocably lost. The document did not lend itself to any new interpretation. There was no other country to search on the path of the 37th parallel. All that remained was for the Duncan to return to Scotland.

Glenarvan, after consulting with his friends, dealt with the specifics of returning with John Mangles. John inspected his bunkers; they had no more than fifteen days supply of coal remaining. They needed to refuel at the next opportunity.

John proposed to Glenarvan that they set sail for Talcahuano Bay, where the Duncan had already refuelled once, before embarking on her circumnavigation voyage. It was a direct journey and precisely on the 37th degree. Then the yacht, fully stocked, could go south to double Cape Horn, and return to Scotland via the Atlantic.

This plan was adopted, and the order was given to the engineer to build his pressure. Half an hour later, they set course for Talcahuano on a sea worthy of its Pacific name, and at six o’clock in the evening the last mountains of New Zealand disappeared in the warm mists of the horizon.

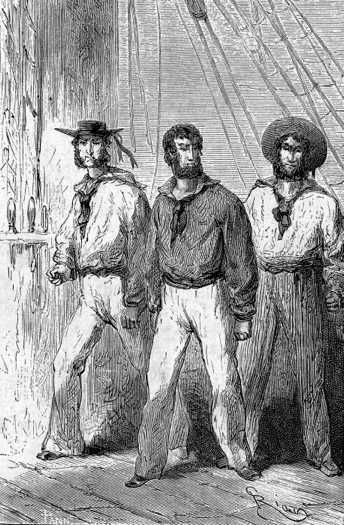

The searcher’s route across New Zealand

Thus, the return journey began. It was a sad crossing for those brave seekers returning to port without bringing back Harry Grant! The crew, so happy and confident at at the outset, was now returning to Europe vanquished and discouraged. Of these brave sailors, no one felt moved by the thought of seeing his country again, and they all would have been willing to continue facing the perils of the sea for a long time, to find Captain Grant.

The cheers that had hailed Glenarvan on his return, were soon followed by discouragement. There were no more of those incessant discussions between the passengers, none of those conversations which once brightened up the journey. Everyone was keeping aloof, in the solitude of their cabins, and rarely did anyone appear on the Duncan’s deck.

Paganel: the man in whom the feelings on board, painful or joyful, were usually exaggerated, Paganel: who, if need be, had invented hope, remained dull and silent. He was seldom seen. His natural loquacity and his French vivacity had changed into muteness and despondency. He seemed even more completely discouraged than his companions. If Glenarvan spoke of resuming his search, Paganel shook his head like a man who does not hope for anything, and who seemed convinced as to the fate of the castaways of the Britannia. He believed them irrevocably lost.

There was one man on board who could provide the last word on this catastrophe, but who maintained his silence. It was Ayrton. There was no doubt that this wretch knew, if not the truth about the present situation of the captain, at least the place of the shipwreck. But Grant would obviously be a witness against him, if found, so he stubbornly kept quiet. Hence a seething anger grew, especially among the sailors, who wanted to deal summarily with him.

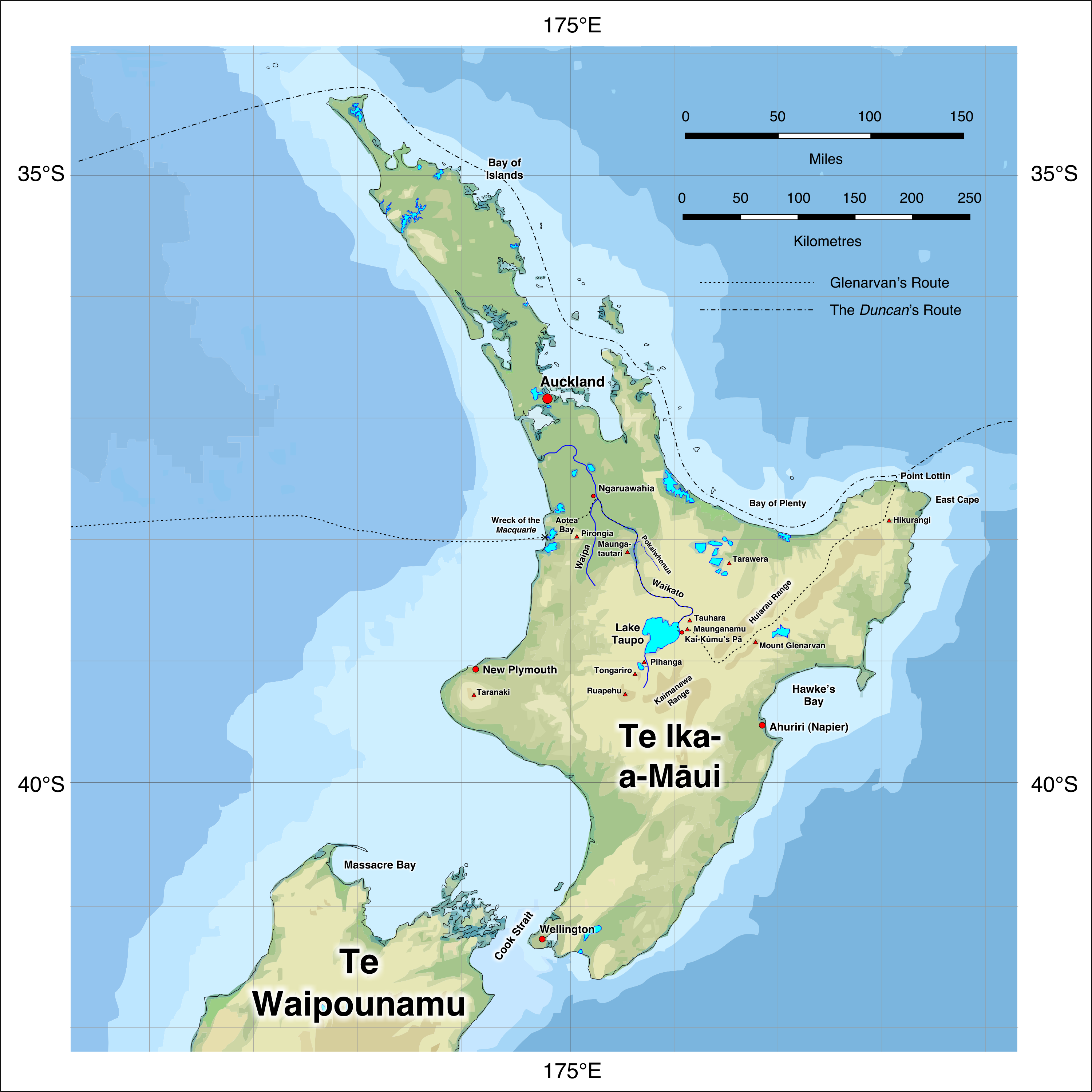

The two women remained shut up with the quartermaster for an hour

Several times Glenarvan renewed his attempts with the quartermaster. Promises and threats were useless. Ayrton’s refusal to speak was so complete, and inexplicable, that the Major came to believe that he knew nothing. This opinion was shared by the geographer, corroborating his particular ideas of Harry Grant’s fate.

But if Ayrton knew nothing, why didn’t he confess his ignorance? It couldn’t be turned against him. His silence increased the difficulty of forming a new plan. Was it possible to deduce the presence of Harry Grant on the continent of Australia, from the meeting of the quartermaster there? It was decided that at all costs, Ayrton had to explain himself on that subject.

Lady Helena, seeing her husband’s failure, asked permission to take her own turn against the obstinacy of the quartermaster. Where a man had failed, perhaps a woman’s gentle influence might succeed. Is it not an eternal fable that while the strongest hurricane may not tear the cloak from a traveller’s shoulders, the slightest ray of sunshine will make him gladly shed it? Glenarvan, knowing the intelligence of his young wife, left her free to act.

On that day, March 5th, Ayrton was brought to Lady Helena’s saloon. Mary Grant attended the interview because the girl might have a great influence on him, and Lady Helena did not want to overlook any chance of success.

The two women remained shut up with the quartermaster of the Britannia for an hour, but nothing came from their conversation. What they said, the arguments they used to extract the convict’s secret, all the details of this interrogation remained unknown. Moreover, when Ayrton left them, they did not seem to have succeeded, and their faces showed a profound discouragement.

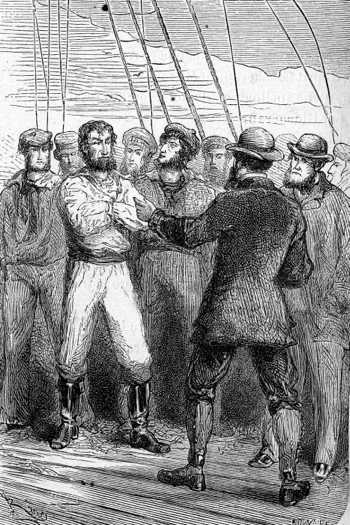

So when the quartermaster was escorted across the deck, back to his cabin, the sailors greeted him with violent threats. He only shrugged his shoulders, which increased the fury of the crew, and it took the intervention of John Mangles and Lord Glenarvan to restrain it.

Ayrton only shrugged his shoulders

But Lady Helena did not give up her campaign. She wanted to struggle to the end against this pitiless soul, and the next day she went to Ayrton’s cabin herself, to avoid a repetition of the last day’s scene on the deck.

For two long hours the good and gentle Scottish woman remained alone, face to face, with the chief of the convicts. Glenarvan, in nervous agitation, lurked outside the cabin, sometimes determined to see this last chance for success through to the end, sometimes to tear his wife away from this painful conversation.

But this time, when Lady Helena reappeared, her features exuded confidence. Had she stirred the last threads of pity in the heart of this wretch, and snatched the secret?

MacNabbs, who saw her first, could not restrain a very natural expression of incredulity.

Yet the rumour spread quickly among the crew that the quartermaster had finally yielded to Lady Helena. It was like an electric shock. All the sailors assembled on deck faster than if Tom Austin’s whistle had called them there.

Meanwhile Glenarvan rushed up to his wife.

“He spoke?” he asked.

“No,” said Lady Helena. “But, yielding to my pleas, Ayrton wants to see you.”

“Ah! Dear Helena, you have succeeded!”

“I hope so, Edward.”

“Have you made any promise that I must ratify?”

“Only one, my friend. It is that you will use all your influence to soften the fate of this unfortunate man.”

“Good, my dear Helena,” he said. Lady Helena retired to her cabin, accompanied by Mary Grant.

“Have Ayrton brought to me, right now.”

The quartermaster was led to the saloon, where Lord Glenarvan was waiting for him.

1. Verne has “west” here, but Point Lottin is on the northern coast of the northeastern tip of New Zealand — DAS