On the 26th of July, 1864, in a strong north-east breeze, a magnificent yacht was steaming over the waves of the North Channel. The English flag flapped at the mizzen-mast. At the top of the main mast flew a blue standard bearing the initials E. G., embroidered in gold, and surmounted by a ducal coronet. This yacht was the Duncan, and it belonged to Lord Glenarvan, one of the sixteen Scottish peers who sit in the Upper House, and the most distinguished member of the Royal Thames Yacht Club, so famous throughout the United Kingdom.

Lord Edward Glenarvan was on board with his young wife, Lady Helena, and one of his cousins, Major MacNabbs.

A huge fish frolicking in the wake of the yacht

The newly built Duncan had been making a trial trip a few miles outside the Firth of Clyde. She was returning to Glasgow, and the Isle of Arran already loomed in the distance, when the watchman pointed out a huge fish frolicking in the wake of the yacht. Captain John Mangles immediately informed Lord Edward, who climbed to the quarterdeck with Major MacNabbs, and asked the captain what he thought of this animal.

“Really, Your Honour,” said Captain Mangles, “I think it’s a shark, and a fine large one, too.”

“A shark in these waters?”

“There is nothing unusual about that,” said the captain. “If I’m not much mistaken it’s a ‘balance-fish,’1 and those rascals are known in all latitudes, and seas! If Your Honour agrees, and Lady Glenarvan wishes to witness a novel hunt, we’ll soon know what it is.”

“What do you say, MacNabbs?” asked Lord Glenarvan. “Shall we try to catch it?”

“If it pleases you,” said the Major calmly.

“The more of those terrible creatures that are killed the better,” said John Mangles, “so let’s seize the chance. It will not only give us a little diversion, but be doing a good turn.”

“Do it, John,” said Lord Glenarvan, and sent for his wife.

Lady Helena soon joined her husband on deck, quite tempted at the prospect of such exciting sport. The sea was magnificent; the rapid movements of the shark, every vigorous plunge and dart, could easily be followed on its surface.

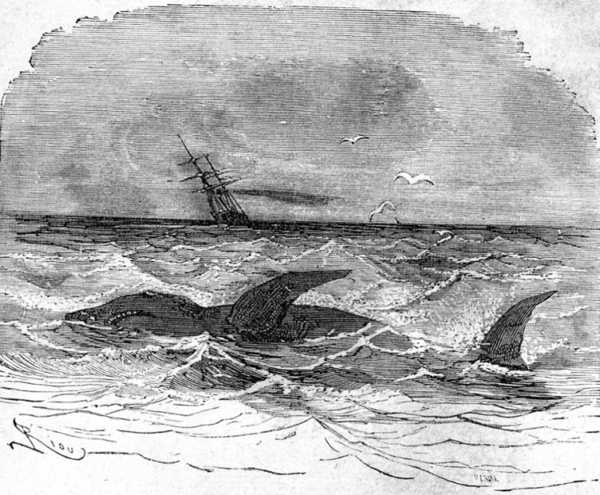

John Mangles gave his orders. The sailors threw a strong rope over the starboard side of the yacht with a big hook at the end of it, concealed in a thick lump of bacon. The shark sensed the bait immediately, though it was still a full fifty yards off. It made rapidly for the yacht, beating the waves violently with its fins, grey at the end, black at their base, while its tail held it in a perfectly straight line. As it got nearer, its great projecting eyes could be seen inflamed with greed, and its gaping jaws uncovered a quadruple row of teeth. Its head was large, and shaped like a double headed hammer. Captain Mangles was right: this was the most voracious specimen of the family of sharks, what the English call the balance-fish.

The passengers and sailors on the Duncan followed all the shark’s movements with keen interest. It soon came within reach of the bait, turned over on his back to seize it, and the bacon and hook vanished into its vast throat. It gave a violent jerk on the rope, and the sailors hauled in the enormous shark by means of tackle attached to the yardarm.

The shark struggled desperately against being removed from its natural element, but its captors were prepared for its violence, and had a long rope ready with a noose which caught its tail and paralyzed its movements. In a few moments it was hoisted up over the side of the yacht and thrown on the deck. A sailor approached it cautiously, and with one powerful stroke of an axe, cut off its tail.

This satisfied the sailors’ vengeance, and there was no longer any reason to fear the shark, but their curiosity was not yet satisfied. It is customary on board any vessel to examine a shark’s stomach carefully. Sharks were well known for their voracious appetites, and the contents of a shark might be worth investigation.

Lady Glenarvan declined to be present at such a disgusting exploration, and withdrew to the cabin again. The fish lay gasping on the deck. It was ten feet long, and weighed more than six hundred pounds. This was nothing extraordinary, for though the balance-fish is not classed among the giants of the sharks, it is always reckoned among the most formidable.

The huge brute was soon unceremoniously ripped open with an axe. The hook had caught in the stomach, which was found to be absolutely empty. Obviously the animal had been fasting for a long time, and the disappointed sailors were just about to throw the remains overboard, when the boatswain’s attention was attracted by a large object sticking fast in its viscera.

“Hey! What’s that?” he cried.

“That,” replied one of the sailors, “is a piece of rock the beast swallowed by way of ballast.”

“No!” said another sailor. “It’s a cannonball that the fellow has swallowed, and couldn’t digest.”

“Be quiet, all of you!” said Tom Austin, the mate of the Duncan. “Don’t you see that it’s a bottle! This animal was a drunkard, and in order not to lose anything he drank not only the wine, but also the bottle?”

“What!” said Lord Glenarvan. “Do you mean to say that the shark has got a bottle in his stomach?”

“What!” said Lord Glenarvan. “Do you mean to say that the shark has got a bottle in his stomach?”

“It’s really a bottle,” said the boatswain, “but not from the wine cellar.”

“Well, Tom, be careful how you take it out,” said Lord Glenarvan, “for bottles found in the sea often contain valuable documents.”

“You think?” said Major MacNabbs.

“It might, at any rate.”

“Oh! I’m not saying it doesn’t,” said the Major. “There may perhaps be some secret in it.”

“That’s just what we’re to see,” said Glenarvan. “Well, Tom?”

“Here it is,” said the mate, holding up a shapeless lump he had managed to pull, with some difficulty, from the shark’s stomach.

“Well, get the ugly thing washed, and bring it to the cabin.”

Tom obeyed, and this bottle — found in such singular circumstances — was placed on the table of the saloon, around which Lord Glenarvan, Major MacNabbs, Captain John Mangles, and even Lady Helena took their places, for women, they say, are always a little curious.

Everything is an event at sea. For a moment they all sat silent, gazing at this frail relic, wondering if it told a tale of sad disaster, or only an insignificant message entrusted to the mercy of the waves by some idle navigator?

The only way to know was to examine the bottle. Glenarvan set to work without further delay, with the care of a coroner2 making an inquest, as the most minute of details might lead to an important discovery.

He started with a close inspection of the exterior of the bottle. The neck was long and slender, and around the thick rim there was still an end of wire hanging, though eaten away with rust. The sides were very thick, and strong enough to bear great pressure. It was evidently of Champagne origin. With these bottles, the Aï or Epernay winemakers block carriage wheels, without any evidence of a crack. The bottle had thus been able to bear with impunity the chances of a long peregrination.

“That’s one of Clicquot’s bottles,” said the Major, and as he ought to know, no one contradicted him.

“My dear Major,” said Lady Helena. “What does it matter about the bottle, if we don’t know where it comes from?”

“We shall know that, too, my dear Helena,” said Lord Edward. “And we can already say that it comes from far away. Look at those petrifactions all over it, these different substances almost turned to mineral through the action of sea water! This waif had been tossing about in the ocean a long time before the shark swallowed it.”

“I quite agree with you,” said MacNabbs. “And this fragile vessel, protected by its stone envelope, has been able to make a long journey.”

“But where does it come from?” asked Lady Glenarvan.

“Wait a little, dear Helena, wait. We must have patience with bottles, but if I am not much mistaken, this one will answer all our questions.” And Lord Glenarvan began to scrape away the hard material protecting the neck. Soon the cork made its appearance, but much damaged by the sea water.

“That’s unfortunate,” said Lord Edward, “for if there are any papers in there, they’ll be in very bad shape.”

“That is to be expected,” said the Major.

“But it’s a lucky thing the shark swallowed them, I must say,” added Glenarvan; “for the bottle would have sunk to the bottom before long with such a cork as this.”

“No doubt,” replied John Mangles. “But it would have been better to have fished it up in the open sea. Then we might have found out the road it had come by taking the exact latitude and longitude, and studying the atmospheric and submarine currents; but with such a postman as a shark that goes against wind and tide, there’s no clue whatever to the starting-point.”

“We shall see.” Glenarvan gently pulled out the cork. A strong odour of salt water pervaded the whole saloon.

“Well?” asked Lady Helena.

“I was right!” said Glenarvan. “I see papers inside!”

“Documents! Documents!” exclaimed Lady Helena.

“Only, they seem to be eaten away by moisture,” said Glenarvan, “and it will be impossible to remove them, for they appear to be sticking to the sides of the bottle.”

“Let’s break it,” said the Major.

“I’d rather keep it intact.”

“No doubt you would,” said Lady Helena, “but the contents are more valuable than the bottle, and we’ll have to sacrifice the one for the other.”

The papers were carefully removed, and spread out on the table

“If Your Honour would break off the neck, I think we might remove the papers, without damaging them” suggested John Mangles.

“Try it, my dear Edward,” said Lady Helena.

Lord Glenarvan couldn’t see any other way to proceed, so he decided to break the neck of the precious bottle. He had to use a hammer, for the stony envelope had acquired the hardness of granite. Soon the debris fell on the table, and several pieces of paper were seen adhering to each other, and the inner walls of the bottle. Glenarvan carefully removed, separated, and spread them on the table, while Lady Helena, Major MacNabbs, and Captain Mangles crowded around him.

1. The balance-fish is so named by English sailors because its head has the form of a balance. It is more commonly known today as the hammerhead shark.

2. Officer who investigates criminal cases.