Captain John Mangles

These pieces of paper, half destroyed by the sea-water, had only a few legible words, the indecipherable remains of lines almost entirely erased. Lord Glenarvan examined them carefully for a few minutes; he turned them around; he held them up to the light; he observed the least traces of writing left by the sea; then he looked at his friends, who regarded him anxiously.

“There are three distinct documents here,” he said. “Apparently copies of the same document in three different languages. One in English, the second in French, and a third in German. The few words that have survived leave me in no doubt about it.”

“But can you make any sense out of them?” asked Lady Helena.

“That’s hard to say, my dear Helena; the words remaining on these documents are very incomplete.”

“Maybe they compliment each other?” said the Major.

“Very likely they will,” said John Mangles. “It is unlikely for sea-water to have gnawed these pages precisely in the same places, and by bringing these fragments of phrases together, we may find an intelligible meaning.”

“That is what we are going to do,” said Lord Glenarvan. “But let us proceed methodically. Here is the first document.”

The document had the following layout, and words:

June 27, 1862. The three-master Britannia, of Glasgow, sank fifteen hundred leagues from Patagonia, in the Southern Hemisphere, stranding two sailors and their skipper, Harry Grant. They have landed on Maria Theresa Island. Continually plagued by cruel poverty, they threw this document into the sea at 153° of longitude and 37° 11’ of latitude. Bring them assistance, or they are lost.1

“That doesn’t mean much,” said the Major, disappointedly.

“But in any case,” said the captain, “it is English.”

“There’s no doubt of it,” said Glenarvan. “The words ‘sank,’ ‘land,’ ‘this,’ and, ‘lost’ are intact; ‘skipp’ is evidently part of the word skipper, and most likely the captain of the shipwrecked vessel’s name begins with ‘Gr’.”

“The meanings of ‘docum’ and ‘sistance’, have plain interpretations, as well,” said Captain Mangles.

“We’ve made good progress, already,” said Lady Helena.

“Yes, but unfortunately we are missing whole lines,” said the Major, “How do we find the name of the lost ship? The place of the sinking?”

“We’ll get to that, in due course,” said Lord Edward.

“I don’t doubt it,” replied the Major, who was naturally agreeable. “But how?”

“By comparing one document with the other.”

“Let’s find out,” said his wife.

The second piece of paper was even more damaged than the first; only a few scattered words remained here and there.

It ran as follows:

27 Juni 1862, die dreimastige Britannia aus Glasgow, verlor sich fünfzehnhundert Meilen von der Patagonien in der südlichen hemisphäre. Auf dem Boden zwei Matrosen und die Kapitän Grant erreichte Tabor Island, dort ständig von grausamer Armut geplagt, Sie warfen dieses Dokument um 153 ° Länge und 37 ° 11 ‘von Breitengrad. bring ihnen Hilfe, aber sie sind verloren.

“This is written in German,” said John Mangles as soon as he glanced at the paper.

“And you know that language, John?” asked Lord Glenarvan.

“Perfectly, Your Honour.”

“Then tell us what these words mean.”

The captain examined the document carefully. “Well, first we have a date: ‘7 Juni’ means June 7; and if we put that before the figures ‘62’ from the English document, it gives us the complete date: 7th of June, 1862.”

“Excellent!” exclaimed Lady Helena. “Go on, John!”

“On the next line,” continued the young captain, “there is the syllable ‘Glas’ and if we add that to the ‘gow’ we found in the English paper, we get the whole word Glasgow. The documents evidently refer to some ship that sailed out of the port of Glasgow.”

“That is my opinion,” said the Major.

“The next line is entirely missing,” said the captain; “but further down are two important words: ‘zwei,’ which means two, and ‘atrosen,’ likely matrosen, the German for sailors.”

“Then I suppose it is about a captain and two sailors,” said Lady Helena.

“It seems so,” replied Lord Glenarvan.

“I must confess, Your Honour, that the next word, ‘grau,’ puzzles me. I can make nothing of it. Perhaps the third document may throw some light on it. The last two words are plain enough. ‘Bring ihnen’ means bring them, and if we combine them with the line of the English paper where we had assistance, we get: Bring them assistance.”

“Yes, that must be it,” said Lord Glenarvan. “But where are the poor fellows? We have not the slightest indication of the place, nor of where the catastrophe happened.”

“Let’s hope that the French copy will be more explicit,” said Lady Helena.

“Here it is, then,” said Lord Glenarvan, “and that is in a language we all know.”

Here is the exact facsimile of the third document:

27 juin 1862, le trois-mâts Britannia, de Glasgow, s’est perdu à quinze cents lieues de la Patagonie, dans l’hémisphère austral. Portés à terre, deux matelots et le capitaine Grant ont atteint à l’île Tabor, là, continuellement en proie à une cruelle indigence, ils ont jeté ce document par 153° de longitude et 37° 11′ de latitude. Venez à leur secours, ou ils sont perdus.

“There are numbers!” cried Lady Helena. “See gentlemen! See!”

“Let us be orderly,” said Lord Glenarvan, “and begin at the beginning. I think we can make out from the incomplete words in the first line that it is a three-master, whose name, from the fragments of the English papers is the Britannia. As to the next two words, ‘gonie’ and ‘austral,’ it is only austral2 that has any meaning to us.”

“That is a precious detail,” said John Mangles. “The shipwreck occurred in the southern hemisphere.”

“That’s vague,” said the Major.

“Well, we’ll go on,” resumed Glenarvan. “Here is the word ‘abor’; that is clearly the root of the verb aborder. The poor men have landed somewhere; but where? ‘Contin.’ Does that mean continent? ‘Cruel’!”

“Cruel!” interrupted John Mangles. “I see now what ‘grau’ is part of in the second document. It is grausam, the word in German for cruel!”

“Let us go on! Let us go on!” said Lord Glenarvan, becoming quite excited over his task, as the meanings of the incomplete words took form. “’Indi.’ Is it India where they have been shipwrecked? And what can this word ‘ongit’ be part of? Ah! I see! It is longitude; and here is the latitude, ‘37° 11′.’ That is a precise indication at last, then!”

“But the longitude is missing,” said MacNabbs.

“But we can’t have everything, my dear Major; and it is something at any event, to have the exact latitude. The French document is decidedly the most complete of the three; and it is plain enough that each is the literal translation of the other, for they all contain exactly the same number of lines. What we have to do now is to put together all the words we have found, translated into one language, and try to ascertain their most probable and logical meaning.”

“Well, what language shall we choose?” asked the Major. “English, German, or French?”

“I think we had better keep going in English, as that was evidently the native tongue of the author, as well as ours.”3

“Your Honour is correct,” said John Mangles.

“Very well. I am going to write this document by bringing together these remnants of words and fragments of sentences, respecting the intervals which separate them, completing those whose meaning can not be doubtful; then, we will compare and judge.”

Glenarvan immediately took the pen, and a few minutes later he presented to his friends a paper on which were drawn the following lines:

June 7, 1862, the three-master Britannia, of Glasgow, sank fifteen hundred leagues distant from Patagonie, in the southern hemisphere. on the coast, two sailors and their skipper Grant landed on Tabor Island. There, continually preyed by cruel indigence, they thrown this document at 153° of longitude and 37° 11′ of latitude. Bring them assistance, or they are lost.

As he was finishing, one of the sailors came to inform the captain that the Duncan was entering the Firth of Clyde, and to ask what were his orders.

“What are Your Honour’s intentions?” asked John Mangles, addressing Lord Glenarvan.

“To get to Dumbarton as quickly as possible, John; Lady Helena will return to Malcolm Castle, while I go on to London and lay this document before the Admiralty.”

Captain John Mangles

John Mangles gave his orders accordingly, and the sailor went to deliver them to the mate.

“Now, friends,” said Lord Glenarvan, “let us continue our research, for we are on the trail of a great catastrophe, and the lives of several men may depend on our wisdom. We must put all our intelligence into the solution of this enigma.”

“We are ready, my dear Edward,” said Lady Helena.

“First of all, there are three very distinct things to be considered in this document. One, the things we know; two, the things we may conjecture; and three, the things we do not know.

“What are those we know? We know that on the 7th of June a three-mast vessel, the Britannia of Glasgow, sank; that two sailors and the captain threw this document into the sea at 37° 11′ of latitude, and they ask for help.”

“Perfectly,” said the Major.

“What can we conjecture?” said Glenarvan. “First, that the shipwreck occurred in the southern seas; and here I would draw your attention at once to the incomplete word gonie. Doesn’t the name of a country strike you even in the mere mention of it?”

“Patagonia!” exclaimed Lady Helena.

“Undoubtedly.”

“But is Patagonia crossed by the 37th parallel?” asked the Major.

“That is easy to check,” said the captain, unfolding a map of South America. “Yes, it is; Patagonia just touches the 37th parallel. It cuts through Araucanía, goes over the Pampas — northern Patagonian lands — and loses itself in the Atlantic.”

“Well, let’s continue with our conjectures. The two sailors and the captain land … land where? Contin … on a continent; on a continent, mark you, not an island. What becomes of them? There are two letters here providentially which give a clue to their fate: ‘pr,’ that must mean prisoners, and cruel Indian is evidently the meaning of the next two words. These unfortunate men are captives in the hands of cruel Indians. Don’t you see it? Don’t the words seem to come of themselves, and fill in the blanks? Isn’t the document quite clear now? Isn’t the meaning self-evident?”

Glenarvan spoke with conviction, and his eyes burned with confidence. His enthusiasm was contagious, for the others all exclaimed, “Yes, it’s obvious, quite obvious!”

After a moment, Lord Edward went on. “All these hypotheses, my friends, seem to me extremely plausible; the disaster took place on the shores of Patagonia, but still I will have inquiries made in Glasgow, as to the destination of the Britannia, and we shall know if it is possible she could have been wrecked on those shores.”

“Oh, there’s no need to send so far to find that out,” said John Mangles. “I have the Mercantile and Shipping Gazette here, which should tell us all about it.”

“Come on, let’s see!” said Lady Glenarvan.

John Mangles took a bundle of newspapers from the year 1862 and quickly flipped through it. His search did not take long, and soon he said with a tone of satisfaction: “May 30, 1862, Peru-Callao, with cargo for Glasgow, the Britannia, Captain Grant.”

“Grant!” exclaimed Lord Glenarvan. “That is the bold Scot who wanted to found a New Scotland in the Pacific Seas!”

“Yes,” replied John Mangles, “The same person who, in 1861, sailed from Glasgow in the Britannia, and has not been heard of since.”

“No doubt! No more doubt!” said Glenarvan. “It’s him. The Britannia left Callao on the 30th of May, and on the 7th of June, eight days after her departure, she is lost on the coast of Patagonia. We find her entire story in these remnants of words that seemed indecipherable. You see, my friends, our conjectures hit the mark very well; we know all now except one thing, and that is the longitude.”

“That is not needed now,” said John Mangles. “We know the country. With the latitude alone, I could undertake to go straight to the scene of the sinking.”

“We know everything, then?” said Lady Helena.

“All, my dear Helena; and those blanks that the sea has left between the words of the document, I will fill without difficulty, as if Captain Grant were dictating to me.”

Lord Glenarvan picked up the pen, and he wrote the following note:

“On the 7th of June, 1862, the three-master, Britannia, of Glasgow, has sunk on the coast of Patagonia, in the southern hemisphere. Making for the shore, two sailors and Captain Grant are about to land on the continent, where they will be taken prisoners by cruel Indians. They have thrown this document into the sea, at longitude ___ and latitude 37° 11′. Bring them assistance, or they are lost.”

“Very good, dear Edward,” said Lady Helena. “If these wretches see their country again, it is you that they will have to thank for it.”

“And they will see it again,” said Lord Glenarvan. “The statement is too explicit, too clear, and too certain for England to hesitate about going to the aid of her children castaway on a desert coast. What she has done for Franklin4 and so many others, she will do today for these poor shipwrecked men of the Britannia.”

“But these wretches doubtless have families who mourn their loss,” said Lady Helena. “Maybe this poor Captain Grant has a wife, children…”

“Very true, my dear lady, and I’ll not forget to let them know that there is still hope. But now, friends, we had better go up on deck, as we must be getting near the harbour.”

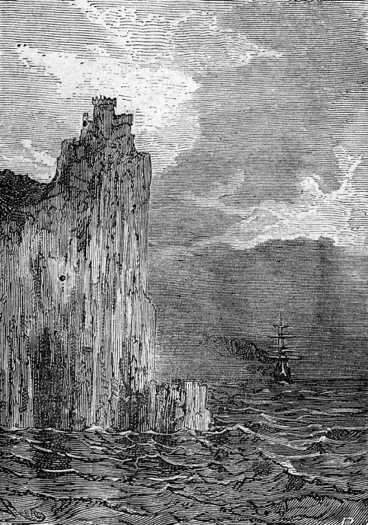

She anchored at the foot of the basaltic rock of Dumbarton

In fact, the Duncan was now following the shores of the Isle of Bute at full steam, and passing Rothesay off her starboard side, with its charming little town lying in its fertile valley; then she rushed into the narrowed passes of the gulf, sailed before Greenok, and at six o’clock she anchored at the foot of the basaltic rock of Dumbarton, crowned by the famous Wallace Castle, of the Scottish hero.

A carriage was hitched there, to take Lady Helena and Major MacNabbs to Malcolm Castle. Lord Glenarvan after kissing his young wife, rushed to catch the express train to Glasgow.

But before leaving he had given a faster agent an important notice, and a few minutes afterward it flashed along the electric telegraph to London, for the following words to appear next day in the Times and Morning Chronicle:

“For information on the fate of the three-master Britannia, of Glasgow, Captain Grant, apply to Lord Glenarvan, Malcolm Castle, Luss, Dumbartonshire, Scotland.”

1. I have made minor tweaks to the wording and formatting of the English version of the document. I don’t know how good Verne’s English was, and some of the word choices in his original look to me like they were translated into English by someone who didn’t know the language very well. Verne had sink instead of sank, aland instead of e land, and that monit (which John took to obviously be a fragment of monition, meaning ‘document’) instead of this docum — DAS

2. French words whose meanings were clear to Lord Glenarvan, and the others: trois: three, austral: southern, jeté: thrown. (Verne had a footnote giving the French translation of some of the legible words in the English document) — DAS

3. Verne’s characters decide to work in French, as that was the language he was writing in — DAS

4. The Franklin Expedition disappeared in the Canadian Arctic in 1845, searching for a Northwest Passage. Their fate remained unknown for many years, and many expeditions were mounted to search for survivors. None were ever found. The wrecks of his two ships, The Erebus, and the Terror, were not found until 2014, and 2016 — DAS