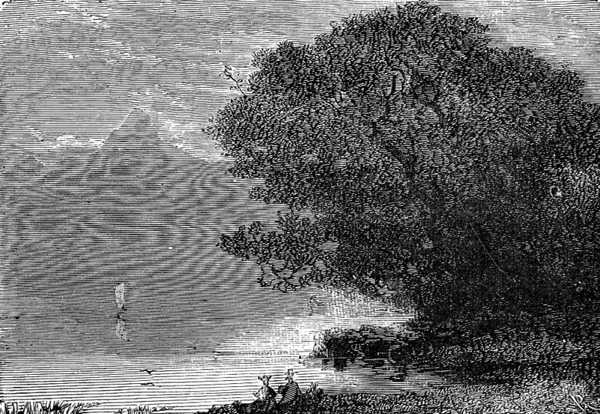

Loch Lomond in moonlight

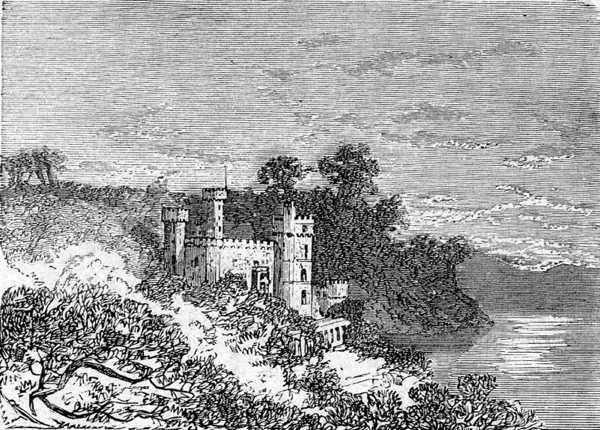

Malcolm Castle, one of the most poetic in the Highlands, is located near the village of Luss, where it dominates the pretty valley. The limpid waters of Loch Lomond bathe the granite of its walls. Since time immemorial it belonged to the Glenarvan family, who kept the old ways of the heroes of Walter Scott in the country of Rob Roy and Fergus MacGregor. At the time when the social revolution was taking place in Scotland, many people were driven off the land who could not pay heavy rents to the old clan chiefs. Some died of hunger; some became fishermen; others emigrated. It was a time of great despair.

The Glenarvans believed that fidelity bound the great and the small, and they remained faithful to their tenants. No one was evicted from the home in which he had been born, nor from the land where his ancestors rested; all remained in the clan of their old lords. At this time, in this century of disaffection and disunity, the Glenarvan family considered the Scots at Malcolm Castle as well as on board the Duncan, as their own people. All were descended from vassals of MacGregor, MacFarlane, MacNabbs, and MacNaughton. They were children of the counties of Stirling and Dumbarton: brave people, devoted body and soul to their master, and some of whom still spoke the Gaelic of Old Caledonia.

Loch Lomond in moonlight

Lord Glenarvan’s fortune was enormous, and he spent it to do much good. His kindheartedness was even greater than his generosity, for the one knew no bounds, while the other, of necessity, had its limits. As Lord of Luss and “laird” of Malcolm, he represented his county in the House of Lords; but, with his Jacobite ideas, he little pleased the House of Hanover, and he was looked upon coldly by the statesmen of England, because of the tenacity with which he clung to the traditions of his forefathers, and his energetic resistance to the political encroachments of Southerners.

And yet he was not a man behind the times, and there was nothing little or narrow-minded about him; but while always keeping his ancestral county open to progress, he remained Scottish at heart, and it was for the honour of Scotland that he competed in the yacht races of the Royal Thames Yacht Club.

Edward Glenarvan was thirty-two years old. He was tall in person, and had rather sharp features; but there was an exceeding sweetness in his look, and a stamp of Highland poetry about his whole bearing. He was known to be brave to excess, enterprising, chivalrous, a nineteenth-century Fergus; but his goodness excelled every other quality, and he was more charitable than St. Martin himself, for he would have given his entire cloak to the poor people of the Highlands.

He had scarcely been married three months, and his bride was Miss Helena Tuffnell, the daughter of William Tuffnell, the great traveller, one of the many victims of geographical science and of the passion for discovery.

Miss Helena did not belong to a noble family, but she was Scottish, which was worth more than nobility in the eyes of Lord Glenarvan. The Lord of Luss had made this charming, courageous, devoted young woman his life’s companion. When he first met her, she was an orphan, alone, almost without fortune, in her father’s house at Kilpatrick. He saw that the poor girl would be a valiant woman; he married her. Miss Helena was twenty-two years old; she was a fair-haired young woman with blue eyes like the water of Scottish lakes on a beautiful spring morning. Her love for her husband outweighed her gratitude. She loved him as if she had been the rich heiress, and he the abandoned orphan. As for his tenants and servants, they were ready to give their lives for whom they called “our good Lady of Luss.”

Malcolm Castle

Glenarvan and Lady Helena lived happily at Malcolm Castle, amid the beautiful nature of the wild Highlands. They walked in the dark alleys of chestnut and sycamore trees, and on the banks of the lake where rang the pibrochs1 of the old days. They explored the depths of uncultivated gorges in which the history of Scotland is written in secular ruins. They would lose themselves in the birch or larch woods, or amidst the vast fields of yellow heather. They would climb the steep summits of Ben Lomond, or ride on horseback through the abandoned glens; studying, understanding, admiring this poetic land — all these famous sites so valiantly sung of by Walter Scott — still called “the country of Rob Roy.”

In the evening, at nightfall, when “the lantern of MacFarlane”2 was lit on the horizon, they would wander along the bartizans — an old circular gallery that made a chain of battlements to Malcolm Castle — and there, thoughtful, forgotten, and as if alone in the world, they would sit on some detached stone in the midst of the silence of nature while daylight faded from the the summits of the darkening mountains, and the pale moon shone down upon them. They lost themselves in the ecstasy and intimate rapture that loving hearts alone have the secret to on earth.

They walked on the banks of the lake

But Lord Glenarvan did not forget that his wife was the daughter of a great traveller, and he thought it likely that she would inherit her father’s predilections. In the first month of their marriage he had the Duncan built expressly that he might take his bride to the most beautiful lands in the world, and complete their honeymoon by sailing the Mediterranean, and through the clustering islands of the Archipelago. Lady Helena had been overjoyed when her husband showed her the Duncan. What greater happiness could there be than to walk with one’s love through those charming regions of Greece, and to see the honeymoon rise on the enchanted shores of the East?

Lord Glenarvan had gone now to London. The lives of the shipwrecked men were at stake, and Lady Helena was too much concerned about them, herself, to begrudge her husband’s temporary absence. A telegram next day gave her hope that he would return soon, but a letter came that evening that warned her that he might be further delayed, and the morning after brought another, in which he openly expressed his dissatisfaction with the Admiralty.

Lady Helena became anxious as the day wore on. In the evening, when she was sitting alone in her room, Mr. Halbert, the house steward, came in and asked if she would see a young girl and boy who wanted to speak to Lord Glenarvan.

“Local people?” asked Lady Helena.

“No, Madame,” said the steward, “I do not know them. They have just arrived by rail to Balloch, and walked the rest of the way to Luss.”

“Tell them to come up, Halbert.”

In a few minutes a girl and boy were shown in. They were evidently brother and sister, for the resemblance was unmistakable. The girl was about sixteen years old. Her tired pretty face, sorrowful eyes, resigned but courageous look, as well as her neat though poor attire, made a favourable impression. The boy she held by the hand was about twelve, but his face expressed such determination that he appeared quite his sister’s protector.

The girl seemed too shy to utter a word at first, but Lady Helena quickly relieved her embarrassment by saying, with an encouraging smile: “You wish to speak to me, I think?”

“No,” replied the boy, in a firm tone. “Not to you, but to Lord Glenarvan.”

“Excuse him, Madame,” said the girl, with a look at her brother.

“Lord Glenarvan is not at the castle just now,” said Lady Helena, “but I am his wife, and if I can do anything for you—”

“You are Lady Glenarvan?” asked the girl.

“Yes, miss.”

“The wife of Lord Glenarvan, of Malcolm Castle, that put an announcement in the Times about the shipwreck of the Britannia?”

“Yes, yes,” said Lady Helena, eagerly. “And you?”

“I am Mary Grant, Madame, and this is my brother, Robert.”

“I am Mary Grant, Madame, and this is my brother, Robert.”

“Miss Grant, Miss Grant!” exclaimed Lady Helena, drawing the young girl toward her, and taking both her hands and kissing the boy’s rosy cheeks.

“What is it you know, Madame, about the shipwreck? Tell me, is my father still living? Shall we ever see him again? Oh, tell me,” said the girl.

“My dear child,” replied Lady Helena. “Heaven forbid that I should answer lightly such a question. I would not delude you with vain hopes.”

“Oh, tell me all, tell me all, Madame. I’m proof against sorrow. I can bear to hear anything.”

“My poor child, there is but a faint hope; but with the help of Almighty Heaven it is just possible you may one day see your father again.”

“My God! My God!” exclaimed Miss Grant, who could not contain her tears, while Robert covered Lady Glenarvan’s hands with kisses.

As soon as they grew calmer, the girl asked countless questions. Lady Helena told them the story of the document. How the Britannia was lost on the shores of Patagonia; how, after the shipwreck, the captain and two sailors, the only survivors, must have reached the continent; and finally, how they implored the help of the whole world in this document, written in three languages, and abandoned to the caprices of the ocean.

Robert Grant devoured Lady Helena with his eyes while she recited her story, hanging on her every word. His childish imagination evidently retraced all the scenes of his father’s shipwreck. He saw him on the deck of the Britannia, and then struggling with the waves, then clinging to the rocks, and lying at length exhausted on the beach.

More than once he cried out, “Oh, papa! my poor papa!” and hugged his sister close.

Mary Grant sat silent and motionless through Lady Helena’s account, with clasped hands, and all she said when the narration ended, was: “Oh, Madame, may I see the paper, please?”

“I do not have it anymore, my dear child,” said Lady Helena.

“You do not have it?”

“No. Lord Glenarvan has taken it to London, for the sake of your father; but I have told you all it contained, word for word, and how we managed to make out the complete meaning from the fragments of words left — all except the longitude, unfortunately.”

“We can do without that,” said the boy.

“Yes, Mr. Robert,” rejoined Lady Helena, smiling at the child’s sure tone. “And so you see, Miss Grant, you know the smallest details now just as well as I do.”

“Yes, Madame, but I should like to have seen my father’s writing.”

“Well, tomorrow, perhaps tomorrow, Lord Glenarvan will be back. My husband determined to lay the document before the Lords of the Admiralty, to induce them to send out a ship immediately in search of Captain Grant.”

“Is it possible, Madame,” exclaimed the girl, “that you have done that for us?”

“Yes, my dear Miss Grant, and I am expecting Lord Glenarvan back any minute now.”

“Oh, Madame! Heaven bless you and Lord Glenarvan,” said the young girl, fervently, overcome with grateful emotion.

“My dear girl, we deserve no thanks; anyone in our place would have done the same. I only pray the hopes we are leading you to entertain may be realized, but until my husband returns, you will remain at the Castle.”

“Oh, no, Madame. I could not abuse the sympathy you show to strangers.”

“Strangers, dear child!” interrupted Lady Helena. “You and your brother are not strangers in this house, and I should like Lord Glenarvan, when he returns, to be able to tell the children of Captain Grant himself, what is going to be done to rescue their father.”

It was impossible to refuse an invitation given with such heart, and Miss Grant and her brother consented to await the return of Lord Glenarvan to Malcolm Castle.

1. A form of Scottish bagpipe music involving elaborate variations on a theme, typically of a martial or funerary character.

2. The full moon.