It has been said that Lady Helena had a brave and generous soul, and what she had just done proved it without a doubt. Her husband had good reason to be proud of this noble woman, who complemented him in every way. The idea of going to Captain Grant’s rescue had occurred to him in London when his request was refused. It was only the thought of leaving Helena that had prevented him from making the suggestion himself. But now that she, herself, proposed to go, all of his hesitation was gone. The servants of the Castle had hailed the project with loud acclamations — for it was to save their brothers: Scots, like themselves — and Lord Glenarvan cordially joined his cheers with theirs, for the Lady of Luss.

With the decision made, there was not an hour to lose. A telegram was immediately dispatched to John Mangles, with Lord Glenarvan’s orders to take the Duncan to Glasgow right away, and to make preparations for a voyage to the South Seas, and possibly around the world, for Lady Helena was correct that the Duncan was built with such strength and speed that she could safely attempt the circumnavigation of the globe, if necessary.

The Duncan was the finest class of steam yacht. She displaced 210 tons, and the first ships that had landed in the New World, or made the great voyages of the age of exploration — those of Columbus, Vespucci, Pinçon, or Magellan — were much smaller.1

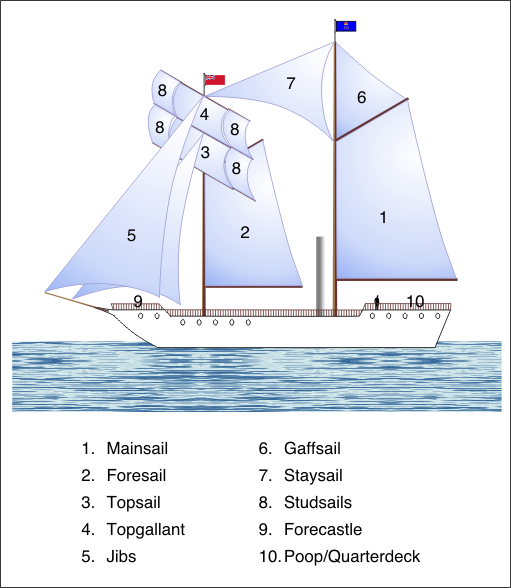

She was a twin masted, topsail schooner. Her mainmast had a fore-and-aft rigged mainsail, and a gaff rigged topsail. Her foremast had a fore-and-aft mainsail, and square rigged topsail and topgallant, like those of a brigantine. She also boasted large and small jibs, and staysails. Her sails allowed her to ride the winds like an ordinary clipper, taking advantage of any favourable breeze, but her main motive power came from her steam engine. This engine, of the latest high-pressure design, produced 160 horsepower, driving a double bladed helical screw. During her trials in the Firth of Clyde the patent-log2 indicated her speed as 17 knots.3 As she was, the Duncan was quite capable of sailing around the world, so John Mangels had only to see to her interior fittings and provisioning, to prepare her for her journey.

His first task was to enlarge the bunkers to carry as much coal as possible, for it might be difficult to get fresh supplies en route. He had to do the same with the store-rooms, and managed so well that he succeeded in laying in enough provisions for two years. Lord Glenarvan had granted him a generous budget, and enough money remained to buy a pivot cannon, which he mounted on the forecastle. There was no knowing what might happen, and it is always good to be able to send an eight pound cannonball over four miles.

John Mangles understood his business. Though he was only the captain of a pleasure yacht, he was one of the best skippers in Glasgow. He was thirty years old, and his rough countenance expressed both courage and goodness. He had been brought up at the castle by the Glenarvan family, and had become an excellent sailor, having already shown skill, energy, and composure in multiple long voyages. When Lord Glenarvan offered him the command of the Duncan, he jumped at the chance, for he loved Lord Glenarvan like a brother, and this was an opportunity to serve him as he had always wanted to.

Tom Austin, the mate, was an old sailor, worthy of all confidence. The crew, consisting of twenty-five men, including the captain and mate, were all from Dumbartonshire, experienced sailors, and all came from the Glenarvan estate. They formed a regular clan, and even carried a traditional bagpiper4 with them. They made a loyal crew for Lord Glenarvan, skilled in their calling, devoted, full of courage, and as practiced in handling fire-arms as maneuvering a ship; a valiant little troop, ready to follow him anywhere, even on the most dangerous expeditions. When the crew heard where they were bound, they could not restrain their enthusiasm, and the rocks of Dumbarton rang again with their joyous outbursts of cheers.

While John Mangles made the stowage and provisioning of the yacht his chief business, he did not forget to arrange the apartments of Lord and Lady Glenarvan for a long trip, as well. He had to prepare cabins for Captain Grant’s children too, for Lady Helena could not turn down Mary’s request to follow her aboard the Duncan.

As for young Robert, he would have smuggled himself in the hold of the Duncan, rather than be left behind. It was impossible to resist the little fellow, and indeed, no one tried. He refused to go as a passenger, but insisted that he must serve in some capacity: as a cabin-boy, like Nelson or Franklin; an apprentice, or a sailor; he did not care which. So he was put in the charge of John Mangles, to be properly trained for his vocation.

“And I hope he won’t spare me the ‘cat-o-nine-tails’5 if I don’t do properly,” said Robert.

“Rest easy on that score, my boy,” said Lord Glenarvan, gravely. He did not add, that this mode of punishment was forbidden on board the Duncan, and moreover, was quite unnecessary.

Next on the roll of passengers was Major MacNabbs. The Major was about fifty years of age, with a calm face and regular features. He was a man who did whatever he was told, of an excellent, even temper; modest, silent, peaceable, and amiable; agreeing with everybody on every subject, never arguing, never getting angry. He wouldn’t move a step quicker, or slower, whether he walked upstairs to bed or mounted a breach. Nothing could excite him, and nothing could disturb him, not even a cannon ball, and no doubt he would die without ever having known a passing feeling of irritation.

This man was endowed in eminent degree not only with ordinary animal courage, that physical bravery of the battle-field, but he had what is far nobler: moral courage, firmness of soul. If he had any fault it was his being so intensely Scottish from head to toe, a pure Caledonian, an obstinate stickler for all the ancient customs of his country. This was the reason he would never serve in England, and he gained his rank of major in the 42nd regiment, the Highland Black Watch, composed entirely of Scottish noblemen. As a cousin of Glenarvan’s, he lived in Malcolm Castle, and as a major it was quite natural that he went with the Duncan.

Such, then, were the personnel of this yacht, so unexpectedly called to make one of the most marvellous voyages of modern times. From the hour the Duncan reached the steamboat quay at Glasgow, she completely monopolized the public attention. A considerable crowd visited her every day, and the Duncan was the only topic of interest and conversation, to the great irritation of the other captains in the port, especially of Captain Burton, in command of the Scotia, a magnificent steamer lying close beside her, and soon to depart for Calcutta.

Considering her size, the Scotia might justly look upon the Duncan as a mere fly-boat,6 and yet this pleasure yacht of Lord Glenarvan’s was the centre of attention, and the excitement about her increased daily.

John Mangles’ work brought the moment of departure quickly upon them. A month after her tests in the Firth of Clyde, the Duncan, stowed, stocked, and laid out, was ready to go to sea. The departure was set for August 25th, which would have the yacht arriving in the southern hemisphere at the beginning of spring.

Many people opposed Lord Glenarvan, as soon as his plan was made public, and warned him of the difficulties and dangers of the journey as he prepared to leave Malcolm Castle. The majority declared itself for the Scottish lord, and all the newspapers, with the exception of the “government organs,” unanimously condemned the conduct of the Admiralty in this affair. Lord Glenarvan was indifferent to either criticism or praise; he did his duty as he saw it, and cared little for the rest.

On August 24th, Lord Glenarvan, Lady Helena, Major MacNabbs, Mary and Robert Grant, Mr. Olbinett — the Yacht Steward — and his wife Mrs. Olbinett — attached to the service of Lady Glenarvan — left Malcolm Castle, having received the touching farewells of the servants of the family. A few hours later, they were on board the Duncan. The people of Glasgow welcomed Lady Helena, the young and courageous woman who renounced the tranquil pleasures of a life of luxury and flew to the rescue of the castaways.

The apartments for Lord Glenarvan and his wife occupied the rear quarter of the Duncan in the poop. They consisted of two bedrooms, a parlour, and two washrooms. Then there was a common saloon, surrounded by six cabins, five of which were occupied by Mary and Robert Grant, Mr. and Mrs. Olbinett, and Major MacNabbs. John Mangles and Tom Austin had cabins in the forecastle, which opened onto the deck. The crew was comfortably lodged below deck, for the yacht carried no cargo other than her coal, provisions, and arms. John Mangles had not stinted on the interior fittings.

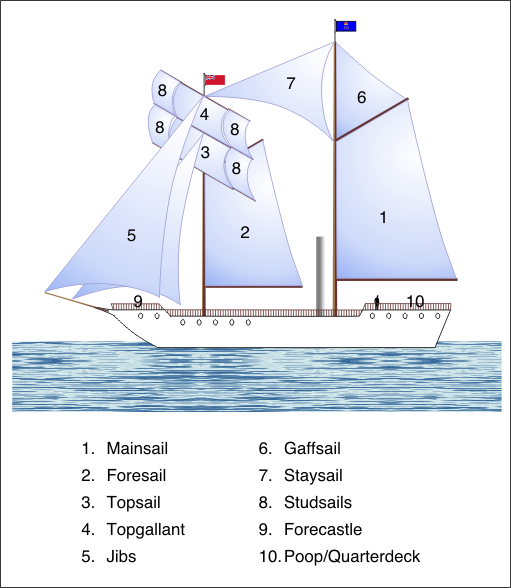

Reverend Morton implored the blessings of Heaven and put the expedition under the care of Providence

The Duncan was to leave at three o’clock on the morning tide of August 25th. But before that, the people of Glasgow witnessed a moving ceremony. At eight o’clock in the evening of the 24th, Lord Glenarvan and his guests, the whole crew, from the stokers to the captain — all who were to take part in this journey — abandoned the yacht and went to St. Mungo’s, the old Glasgow Cathedral. This ancient church, so marvellously described by Walter Scott, remains intact amid the ruins of the Reformation. It was there, in the grand nave beneath its lofty arches, in the presence of an immense crowd, and surrounded by tombs as thickly set as in a cemetery that Reverend Morton implored the blessings of Heaven, and put the expedition under the care of Providence. There was a moment when Mary Grant’s voice rose in the old church. The girl prayed for her benefactors and poured before God the sweet tears of gratitude. The assembly was deeply moved as it withdrew.

At eleven o’clock the passengers and crew returned on board the Duncan. John Mangles and the crew began their final preparations. At midnight, the boilers were lit, and soon billows of black smoke mingled with the mists of the night. The sails of the Duncan had been furled and carefully stowed in canvas holsters to protect them from the pollution of the coal, for the wind was blowing from the southwest. She would depart under steam power alone.

At two o’clock the Duncan began to shudder with the quivering of her boilers; the pressure gauge indicated a full head of steam, with a pressure of four atmospheres; the heated steam whistled through relief valves; the tide was running; the twilight already made it possible to see the Clyde channel between the beacons and the biggings7 whose lanterns were gradually fading before the dawn. It was time to leave.

John Mangles called Lord Glenarvan, who immediately climbed the bridge.

Soon the ebb-tide was felt; the Duncan blew vigorous whistles in the air, dropped her moorings, and separated herself from the surrounding ships. The screw was set in motion and pushed the yacht into the river channel. John had not taken on a pilot, for he knew the channels of the Clyde well, and no one on board was better able to maneuver her. The yacht responded silently and surely to his slightest touch, with his right hand controlling the engine order telegraph, and his left the helm. Soon the last factories of Glasgow gave way to the villas raised on the riverine hills, and the rumours of the city faded in the distance.

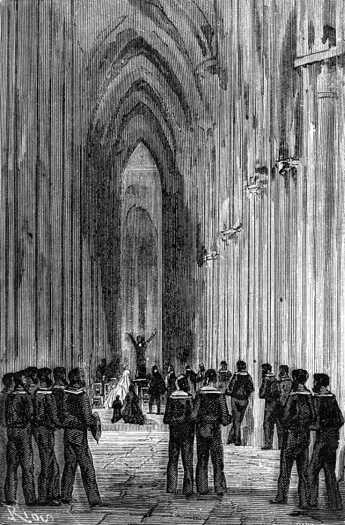

The Duncan doubled the Mull of Cantyre, and sailed into the open ocean

An hour after departing Glasgow, the Duncan raised the rocks of Dumbarton; two hours later she was in the Firth of Clyde; at six o’clock in the morning she doubled the Mull of Cantyre, left the northern channel, and sailed into the open ocean.

1. The fourth voyage of Christopher Columbus was undertaken with four ships. The largest, the caravel Capitana, commanded by Columbus, displaced 70 tons; the smallest only 50. They were real coasters.

2. The patent-log is an instrument which, by means of needles rotating on a graduated circle, indicates the speed of the ship.

3. 17 nautical miles per hour. The nautical mile being 1852 metres, 17 knots is nearly 32km/h, or 20mph.

4. The bagpiper who still exists in Highlander regiments.

5. It is a martinet composed of nine belts, very much in use in the English navy.

6. Riverboat.

7. Small mounds of stones marking the channel of the Clyde.

I can find no reference to “biggings” as any sort of channel marker, but I'm assuming that it’s a perfectly cromulent, if obscure, word for such things, since Verne used it, but still felt the need to footnote it. — DAS