He was a tall, thin, withered-looking man, about forty years old

The ocean was rough on the Duncan’s first day at sea, and the yacht tossed and pitched in the waves. The wind freshened toward evening, so the ladies didn’t appear on the quarterdeck, but chose to remain in their cabins.

But the wind changed the next morning, and Captain Mangles ordered the men to put up the foresail, topsail, and topgallant, which steadied the vessel on the waves, lessening her rolling and pitching. Lady Helena and Mary Grant were able to join Lord Glenarvan, Major MacNabbs, and the captain on the deck at dawn.

The sunrise was magnificent. The day star rose from the ocean like an electroplated golden disc from its immense voltaic bath. The Duncan slipped through this splendid irradiation with her sails stretched out to catch the sun’s rays. The yacht’s passengers watched the rising of the radiant star in a silent contemplation.

“What a beautiful sight!” said Lady Helena. “This is the beginning of a beautiful day. May the winds continue to blow fair for the Duncan.”

“It would be impossible to desire a better one, my dear Helena,” said Lord Glenarvan, “and we have no reason to complain of this beginning of the journey.”

“Will the crossing be long, my dear Edward?”

“It’s up to Captain John to answer us,” said Glenarvan. “Do we go well? Are you satisfied with your ship, John?”

“Very satisfied, Your Honour,” replied John. “It is a marvellous ship, and a sailor likes to feel the sea under his feet. Never have I felt a hull and engine better matched. You see how smooth the wake of the yacht is, and how easily she cuts through the waves? We sail at seventeen knots. If we maintain this speed, we will cross the Equator in ten days, and in five weeks we will have doubled Cape Horn.”

“You hear, Mary,” said Lady Helena. “Five weeks!

“Yes, Madame,” said the girl, “I hear, and my heart beats very hard at the captain’s words.”

“And how do you find the sea, Miss Mary?” asked Lord Glenarvan.

“Pretty well, My Lord. I am not very much inconvenienced by it. Besides I shall soon get used to it.”

“And our young Robert?”

“Oh, as for Robert,” said the captain, “whenever he is not poking about down below in the engine room, he is perched somewhere aloft among the rigging. A youngster like that laughs at sea-sickness. Why, look at him this very moment! Do you see him?”

The captain pointed toward the foremast, and sure enough there was Robert, hanging on the yards of the topgallant, a hundred feet above the deck. Mary involuntarily gave a start.

“Oh, don’t be afraid, Miss Mary," said the captain. “He is all right, take my word for it. I’ll have a capital sailor to present to Captain Grant before long, for we’ll find the worthy captain, depend upon it.”

“Heaven grant it, Mr. John,” said the young girl.

“My dear child,” said Lord Glenarvan, “there is something so providential in the whole affair, that we have every reason to hope. We are not going, we are led; we are not searching, we are guided. And look at all the brave men who have enlisted in the service of this good cause. We shall not only succeed in our enterprise, but there will be little difficulty in it. I promised Lady Helena a pleasure trip, and if I am not mistaken, I will keep my word.”

“Edward,” said his wife, “you are the best of men.”

“Not at all, but I have the best of crews and the best of ships. Do you not admire the Duncan, Miss Mary?”

“On the contrary, My Lord, I do admire her, and I’m a connoisseur in ships,” said the young girl.

“Indeed?”

“Yes. I have played all my life on my father’s ships. He should have made me a sailor, for I dare say, at a push, I could reef a sail or braid a lanyard, easily enough.”

“Do you say so, miss?” asked John Mangles.

“If you talk like that you and John will be great friends, for he can’t think any calling is equal to that of a seaman; he can’t fancy any other, even for a woman. Isn’t it true, John?”

“Quite so,” said the young captain, “and yet, Your Honour, I must confess that Miss Grant is more in her place on the poop than reefing a topsail. But for all that, I am quite flattered by her remarks.”

“And especially when she admires the Duncan,” said Glenarvan.

“Well, really,” said Lady Glenarvan, “you are so proud of your yacht that you make me wish to look over all of it; and I should like to go down and see how our brave men are lodged.”

“Their quarters are first-rate,” said John. “They are as comfortable as if they were at home.”

“And they really are at home, my dear Helena,” said Lord Glenarvan. “This yacht is a portion of our old Caledonia, a fragment of Dumbartonshire, making a voyage by special favour, so that in a manner we are still in our own country. The Duncan is Malcolm Castle, and the ocean is Loch Lomond.”

“Very well, my dear Edward, do us the honours of the Castle then.”

“At your service, Madame; but let me tell Olbinett first.”

The steward of the yacht was an excellent butler, a Scot, who might have been French for his airs of importance, but he discharged his functions with zeal and intelligence. He appeared promptly when summoned.

“Olbinett, we are going to have a tour of the ship before breakfast.” said Glenarvan, as if he was proposing a walk to Tarbert or Loch Katrine. “I hope we shall find the table served when we come back.”

Olbinett bowed gravely.

“Are you coming with us, Major?” asked Lady Helena.

“If you command me,” said MacNabbs.

“Oh, the Major is absorbed in his cigar,” said Lord Glenarvan. “You mustn’t tear him from it. He is an inveterate smoker, Miss Mary, I can tell you. He is always smoking, even while he sleeps.”

The Major gave an assenting nod, and Lord Glenarvan and his party went below.

MacNabbs remained alone, talking to himself, as was his habit, but never contradicting himself. Soon he was enveloped in thick clouds of smoke. He stood motionless, watching the wake of the yacht. After some minutes of this silent contemplation he turned around, and suddenly found himself face to face with a stranger. Certainly, if any thing could have surprised him, this encounter would, for he had never seen the man before in his life.

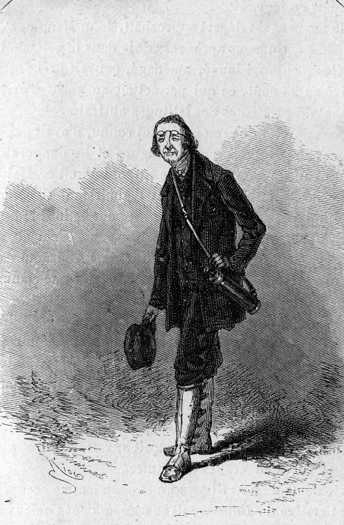

He was a tall, thin, withered-looking man, about forty years old

He was a tall, thin, withered-looking man, about forty years old, resembling a long nail with a big head. His head was large and thick, his forehead high, his nose long, his mouth wide, his chin strongly hooked. His eyes were concealed by enormous round spectacles, and his eyes seemed to have that particular uncertainty of the nyctalop1. His countenance announced that he was an intelligent and happy man. He did not have the forbidding expression of those grave individuals who never laugh on principle, and cover their dull-wittedness with a mask of seriousness. He looked far from that. His careless, good-humoured air, and easy, unceremonious manners, showed plainly that he knew how to take men and things at their best. Though he had not yet opened his mouth, he gave the impression of being a great talker, and moreover, one of those absent minded folks who neither see though they are looking, nor hear though they are listening. He wore a travelling cap, and stout yellow buskins with leather gaiters. His pantaloons and jacket were of brown velvet, and their innumerable pockets were stuffed with note-books and diaries, books, wallets, and a thousand other things as cumbersome they were useless, not to mention a telescope, which he carried slung from a baldric.

The stranger’s excitement was a strong contrast to the Major’s placidity. He walked around MacNabbs, looking at him and questioning him with his eyes without eliciting one remark from the imperturbable Scot, or awakening his curiosity in the least to know where he came from, and where he was going, and how he had got on board the Duncan.

The stranger drew out his telescope and began gazing at the horizon

Finding all his efforts confounded by the Major’s indifference, the mysterious passenger seized his telescope, drew it out to its fullest extent, about four feet, and began gazing at the horizon, standing motionless with his legs wide apart. After gazing at the horizon for five minutes, he lowered the telescope, set it up on deck, and leaned on it as if it had been a cane. The telescope immediately collapsed in on itself so suddenly that he fell full length on deck, and lay sprawling at the foot of the mainmast.

Anyone but the Major would have at least smiled at such a ludicrous sight, but MacNabbs never moved a muscle of his face.

This was too much for the stranger.

“Steward!” he called, with an clearly foreign accent.

He waited a minute, but nobody appeared, and he called again, still louder, “Steward!”

Mr. Olbinett was passing that moment on his way to the galley in the forecastle. He was astonished at hearing himself addressed like this by a lanky individual of whom he had no knowledge, whatever.

“Where can he have come from? Who is he?” he thought to himself. “He can not possibly be one of Lord Glenarvan’s friends?”

However, he went up on the poop, and approached the stranger.

“Are you the steward of this vessel?“

“Yes, sir,” said Olbinett; “but I have not the honour of—”

“I am the passenger in cabin six.”

“Cabin six?” repeated the steward.

“Certainly; and your name, what is it?”

“Olbinett.”

“Well, Olbinett, my friend, we must think of breakfast, and that pretty quickly. It is thirty-six hours since I have had anything to eat, or rather thirty-six hours that I have been asleep — pardonable enough in a man who came all the way, without stopping, from Paris to Glasgow. What is the breakfast hour?”

“Nine o’clock,” replied Olbinett, mechanically.

The stranger tried to pull out his watch to see the time, but it was not until he had rummaged through the ninth pocket that he found it.

“Ah, well,” he said, “it is not yet eight o’clock. Well then, Olbinett, a biscuit and a glass of sherry to wait, because I’m starving.”

Olbinett heard him without understanding what he meant, for the voluble stranger kept on talking incessantly, flying from one subject to another.

“The captain? Isn’t the captain up yet? And the chief officer? What is he doing? Is he asleep too? It is fine weather, fortunately, and the wind is favourable, and the ship goes on quite by herself—”

Just at that moment John Mangles appeared at the top of the stairs.

“Here is the captain!” said Olbinett.

“Ah! Enchanted, Captain Burton,” exclaimed the stranger. “Delighted to make your acquaintance.”

John Mangles stood stunned, as much at seeing the stranger on board as at hearing himself called “Captain Burton.”

But the newcomer went on in the most affable manner. “Let me shake your hand, sir; and if I did not do so yesterday evening, it was only because I did not wish to be troublesome when you were preparing to sail. But today, Captain, it gives me great pleasure to make your acquaintance.”

John Mangles opened his eyes as wide as possible, and looked back and forth between the stranger, and Olbinett.

“Now the introduction is made, my dear Captain, we are old friends,” the fellow rattled on. “Let’s have a little talk, and tell me how you like the Scotia.”

“What do you mean by ‘the Scotia’?” said John Mangles at last.

“By the Scotia why, the ship we’re on, of course — a good ship that has been commended to me, not only for its physical qualities, but also for the moral qualities of its commander, the brave Captain Burton. Would you be some relation of the famous African traveller2 of that name? A bold man. I offer you my congratulations.”

“Sir,” interrupted John. “I am not only no relation to Burton the great traveller, but I am not even Captain Burton.”

“Ah, is that so? Is it Mr. Burdness, the chief officer, that I am talking to at present?”

“Mr. Burdness?” repeated John Mangles, beginning to suspect the truth. He only wondered whether the man was mad, or some heedless rattle pate? He was about to explain the case in a categorical manner, when Lord Glenarvan, his wife, and Miss Grant came back up on the deck.

The stranger caught sight of them “Ah! Passengers!” he exclaimed. “Passengers! Excellent! I hope you are going to introduce me to them, Mr. Burdness!”

But he could not wait for anyone’s introduction, and going up to them with perfect ease and grace, said, bowing to Miss Grant, “Madame;” then to Lady Helena, with another bow, “Miss;” and to Lord Glenarvan, “Sir.”

Here John Mangles interrupted him, and said, “Lord Glenarvan.”

“My Lord,” said the stranger, “I beg your pardon for presenting myself to you, but at sea it is well to relax the strict rules of etiquette a little. I hope we shall soon become acquainted with each other, and that the company of these ladies will make our voyage in the Scotia appear as short as it is pleasant.”

Lady Helena and Miss Grant were too astonished to be able to utter a single word. The presence of this intruder on the poop of the Duncan was perfectly inexplicable.

“Sir,” said Lord Glenarvan, “to whom have I the honour of speaking?”

“To Jacques-Éliacin-François-Marie Paganel, Secretary of the Geographical Society of Paris, Corresponding Member of the Societies of Berlin, Bombay, Darmstadt, Leipzig, London, Petersburg, Vienna, and New York; Honorary Member of the Royal Geographical and Ethnographical Institute of the East Indies; who, after having spent twenty years of his life in geographical work at a desk, wishes to see active service, and is on his way to India to gain for science what information he can by following up the footsteps of great explorers.”

1. A person who has a peculiar construction of the eye which makes their sight imperfect in the day and better at night.

2. Sir Richard Francis Burton (not the actor). 1820 – 1890. Noted explorer, ethnologist, linguist, spy, and translator. One of many explorers who sought the source of the Nile in Central Africa, and known for translating One Thousand and One Arabian Nights, and the Kama Sutra into English.