The condor’s spiral path was converging on an inaccessible crag

The eastern side of the Cordilleras of the Andes consists of a series of long slopes, that blend down almost imperceptibly into the plain on which the portion of the massif had suddenly stopped. In this new country, the soil is carpeted in rich pasture, and bristling with magnificent trees. Many of these were forests of apple trees, planted during the European conquest, and sparkling with golden fruit. It was as if a corner of Normandy had been transplanted to this plateau. The sudden transition from a desert to an oasis, from snowy peaks to verdant plains, from winter to summer, could’t fail to strike the traveller’s eye.

The ground, moreover, had recovered its immobility. The earthquake had subsided, though there was little doubt the subterranean forces were carrying on their devastating work further on, for the Andes are never entirely free from earthquakes. This time the shock had been extremely violent. The outline of the mountains was wholly altered. A new panorama of peaks, ridges, and pinnacles was outlined against the blue background of the sky, and a Pampas guide would have vainly searched it for his accustomed landmarks.

A magnificent day had dawned. The sun was just emerging from its oceanic bed. It had glided beneath the continent and was now rising from the Atlantic. Its bright rays streamed over the Argentinian plains. It was eight o’clock in the morning.

Lord Glenarvan and his companions, revived by the Major’s efforts, gradually came back to life. They were all dizzy, and disoriented, but had sustained no serious injury. They had come down the Cordilleras, and would have applauded how rapidly they had reached the plain, if only the smallest and weakest member of their party, Robert Grant, hadn’t been missing from the roll call.

The brave boy was beloved by everybody. Paganel was particularly attached to him, and so was the Major, for all his apparent coldness. As for Glenarvan, he was desperate when he heard of his disappearance, and pictured the child lying in some deep abyss, wildly crying for help from his second father.

Glenarvan could barely restrain his tears. “My friends! We must look for him. We must look until we find him! We cannot leave him to his fate. Every valley, precipice and abyss must be searched thoroughly. I will be tied with a rope, and go down myself. I insist upon it, you understand, I insist upon it! Heaven grant Robert may be still alive! If we lose the boy, how could we ever dare to meet the father? What right have we to save the captain at the cost of his son’s life?”

Glenarvan’s companions listened to him in silence. They knew that he was looking to them for reassurance that Robert would be found alive, but none of them felt any hope of it.

“Well, you heard me,” said Glenarvan. “What do you have to say? Do you mean to tell me that you have no hope — not the slightest?”

Again there was silence, until MacNabbs asked “Can any of you remember when Robert disappeared?”

No one could say.

“At least,” said the Major, “can one of you tell be who the child was beside during our descent of the Cordilleras?”

“Beside me,” said Wilson.

“Very well. How long did you see him near you? Try to remember.”

“All that I can recollect is that Robert Grant was still by my side, holding fast by a tuft of lichen, less than two minutes before the shock which finished our descent.”

“Less than two minutes? Are you certain? I dare say a minute seemed a very long time to you. Are you sure you are not making a mistake?”

“I don’t think I am. No; it was less than two minutes.”

“Good!” said MacNabbs. “And was Robert to your right or your left?”

“On my left. I remember his poncho whipping past my face.”

“And where were you, with respect to the rest of us?”

“On the left also.”

“So Robert must have disappeared on this side,” said the Major, turning toward the mountain and pointing toward his right. “And considering the time that has elapsed since his disappearance, that the spot where he fell is about two miles up. That is where we must search, dividing the different zones among us, and that’s where we’ll find him.”

Not another word was spoken. The six men commenced their search, keeping constantly to the line they had made in their descent, examining closely every fissure, and going into the very depths of the abysses, choked up though they partly were with fragments of the plateau; and more than one came out again with their clothes torn to rags, and feet and hands bleeding. For long hours they scrupulously searched all this portion of the Andes, with the exception of a few inaccessible crags, without any thought of resting. But it was all in vain. It seemed that the child had not only found his death on the mountain, but also been sealed forever in a stone tomb.

About one o’clock, Glenarvan and his defeated companions met again at the bottom of the valley. Glenarvan was completely crushed with grief. He scarcely spoke. The only words that escaped his lips amid his sighs were “I shall not leave! I shall not leave!”

Every one of the party understood his feelings, and shared them.

“Let us wait,” said Paganel to the Major and Tom Austin. “We will take a little rest, to restore our strength. We need it either way, whether to stay and search some more, or to continue our journey.”

“Yes,” said MacNabbs, “and we will stay, since Edward wishes to stay. He still has hope, but what is it he hopes for?”

“God knows!” said Tom Austin.

Paganel brushed away a tear. “Poor Robert!”

The valley was thickly wooded, and the Major chose a clump of tall carob trees under which they made their temporary camp. All they had remaining were a few blankets, weapons, and a little dried meat and rice. Not far off there was a river, which supplied them with water, though it was still somewhat muddy after the disturbance of the avalanche. Mulrady soon had a fire lit on the grass, and a warm and comforting drink to offer his master. But Glenarvan refused to touch it, and lay stretched prostrate on his poncho.

So the day passed, and night came on, calm and peaceful as the preceding had been. While his companions were lying motionless, though wide awake, Glenarvan ascended once more the slopes of the Cordilleras, listening intently in hope that some cry for help reach him. He ventured high and alone, sometimes placing his ear to the ground, straining to hear anything between the beats of his own heart. He called out in a desperate voice.

He wandered all night in the mountains. Sometimes the Major followed him, and sometimes Paganel, ready to lend a helping hand among the slippery peaks and dangerous chasms into which his recklessness drew him. All his efforts were in vain, and the only response to his repeated cries of “Robert! Robert!” was an echo.

Day dawned, and it was necessary to drag Glenarvan back to the camp from the distant plateaus, in spite of himself. His despair was terrible. None would dare speak to him of departing from this fatal valley. Yet their provisions were exhausted, and the Argentinian guides and horses promised by the catapez to take them across the Pampas were not far off. Backtracking would be more difficult than going forward. Besides, the Duncan would be waiting in the Atlantic. These were strong reasons against any long delay; indeed it was best for all parties to continue the journey as soon as possible.

MacNabbs undertook the task of rousing Lord Glenarvan from his grief. For a long time he spoke without his friend seeming to hear him. At last Glenarvan shook his head, and said, almost inaudibly.

“Go?”

“Yes! Go.”

“Another hour!”

“Yes, we’ll search another hour,” said the worthy Major.

When the hour had passed, Glenarvan begged again for another hour. He sounded like a convict begging for a delay of his execution. They continued like this until noon. MacNabbs and the rest agreed that they could delay no longer. All of their lives depended on setting out at once.

“Yes, yes!” replied Glenarvan. “Let’s go! Let’s go!”

But he spoke without looking at MacNabbs. His gaze was fixed intently on a certain dark speck in the heavens.

“There! There!” Glenarvan extended an arm, pointing to the sky. “Look! Look!”

All eyes turned turned toward the sky in the direction indicated so imperiously. The dark speck was growing. It was a large bird hovering high above them.

“A condor,” said Paganel.

“Yes, a condor,” said Glenarvan. “Who knows? It is coming down. It is getting lower! Let us wait.”

What did Glenarvan hope? Did his reason go astray? “Who knows?” he had said.

Paganel was correct. It was a condor, and getting closer every moment. This magnificent bird, once revered by the Incas, is the king of the southern Andes. It attains an extraordinary size, and prodigious strength in those regions. It has often driven oxen into the depths of chasms. It attacks sheep, colts, and young calves browsing on the plains, and carries them off to inaccessible heights. It is not uncommon for it to hover twenty thousand feet above the ground, far beyond human reach, and it could discern the smallest objects on the ground beneath it. The power of its vision astonished naturalists.

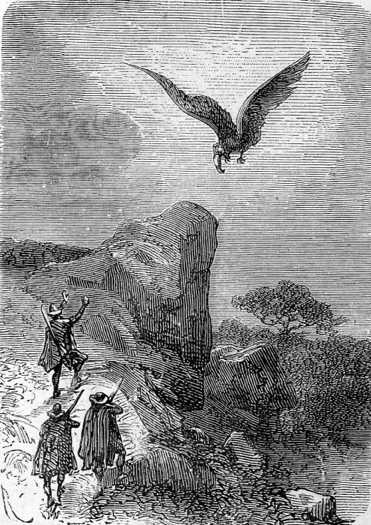

The condor’s spiral path was converging on an inaccessible crag

What had this condor discovered then? Could it be the corpse of Robert Grant? “Who knows?” repeated Glenarvan, keeping his eyes fixed on the bird. The enormous creature was fast approaching, sometimes hovering, and sometimes plummeting like a stone. Presently it began to wheel around in wide circles, less than a hundred fathoms from the ground. They could see it distinctly. It had a wingspan of more than fifteen feet, and its powerful wings bore it along without beating, for it is the prerogative of large birds to fly with calm majesty, while insects have to beat their wings a thousand times a second.

The Major and Wilson had seized their rifles, but Glenarvan stopped them with a gesture. The condor’s spiral path was converging on an inaccessible crag about a quarter of a mile up the side of the mountain. It wheeled round and round with dizzying speed, opening and closing its formidable claws, and shaking his cartilaginous crest.

“He’s there, there!” yelled Glenarvan.

A sudden thought flashed across his mind.

“What if Robert’s still alive?” he cried. “The bird! Fire my friends! Fire!”

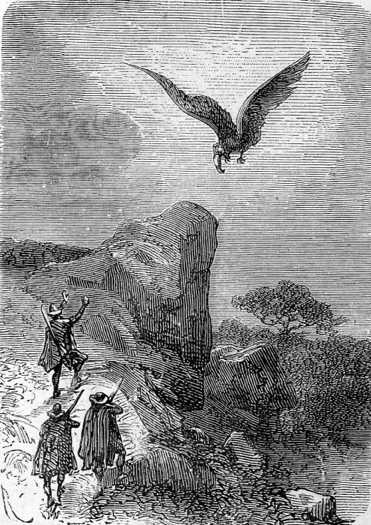

But it was too late. The condor had dropped out of sight behind the crags. Only a second passed, a second that seemed an age, and the enormous bird reappeared, flying slowly under the burden of a heavy load.

The condor had seized Robert by his clothes

A cry of horror rose on all sides. It was a human body the condor had in his claws, dangling in the air, and apparently lifeless — it was Robert Grant. The bird had seized him by his clothes, and was already one hundred and fifty feet in the air. It had caught sight of the travellers, and was flapping its wings violently, endeavouring to escape with its heavy prey.

“Argh!” cried Glenarvan. “It would be better that Robert were dashed to pieces against the rocks, rather than be a—”

He did not finish his sentence, but seizing Wilson’s rifle, took aim at the condor. His arms were trembling too badly, to draw a steady aim.

“Let me do it,” said the Major.

And with a calm eye, and sure hands and motionless body, he aimed at the bird, now three hundred feet above him in the air.

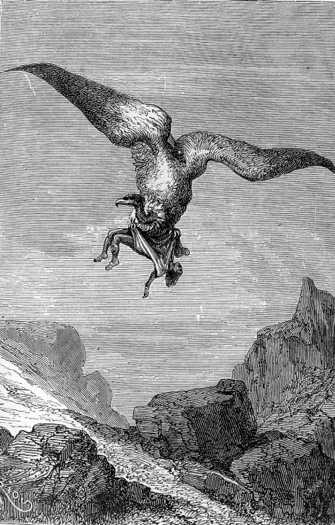

But before he had pulled the trigger the report of a gun resounded from the bottom of the valley. White smoke rose from between two masses of basalt, and the condor, shot in the head, began to fall, spinning, its great wings spread out like a parachute. It had not let go its prey, but gently sank down with it to the ground, about ten paces from the stream.

“We’ve got him, we’ve got him,” shouted Glenarvan; and without waiting to see where the providential shot had come from, he rushed toward the condor, followed by his companions.

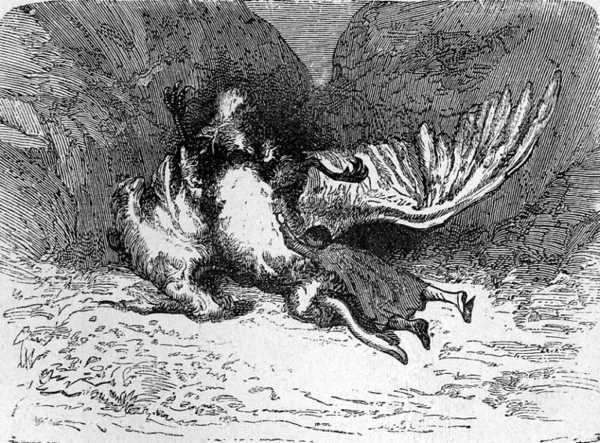

When they reached the spot the bird was dead, and Robert’s body was concealed beneath its broad wings. Glenarvan flung himself on the corpse of the boy, tore it from the condor’s grasp, placed it flat on the grass, and knelt down and put his ear to his chest.

It had not let go of its prey

But a wilder cry of joy never broke from human lips, than Glenarvan uttered the next moment, as he jumped to his feet.

“He’s alive! He’s still alive!”

The boy’s clothes were stripped off in an instant, and his face bathed with cold water. He moved slightly, opened his eyes, looked round and murmured, “Oh, My Lord! It’s you!” he said. “My father!”

Glenarvan could not reply. Emotion suffocated him. He knelt down weeping, beside the child so miraculously saved.