The casucha was an adobe cube, twelve feet on a side

Anyone but MacNabbs might have passed beside, around, or even over the hut a hundred times without noticing it. It was covered in a carpet of snow, and scarcely distinguishable from the surrounding rocks. It had to be cleared, but after half an hour of hard work, Wilson and Mulrady succeeded in digging out the opening to the casucha and the little troop snuggled inside.

The casucha was an adobe cube, twelve feet on a side

This casucha had been built by the Indians from adobes: mud bricks baked in the sun. It was cube shaped, twelve feet on each side, and standing on a block of basalt. A stone stair led up to the door, the only opening, and narrow as this door was, the wind, snow, and hail found their way in when the temporales were unleashed in the mountains.

Ten people could easily fit inside it, and though the walls might be none too water-tight in the rainy season, at this time of the year, at any rate, it was sufficient protection against the intense cold, which, according to the thermometer, was ten degrees below zero1. There was a sort of fireplace in it, with a chimney of bricks, badly enough put together, certainly, but it still allowed for a fire to be lit.

“This will be enough shelter,” said Glenarvan, “even if it is not very comfortable. Providence has led us here, and we can only be thankful.”

“I’d call it a perfect palace,” said Paganel. “We only lack the sentries and courtiers. We shall do capitally here.”

“Especially when we get a good fire blazing in the hearth,” said Tom Austin. “For we are colder than we are hungry, right now. For my part, I would rather see a good faggot than a slice of venison, just now.”

“Well, Tom, we’ll try and get something that will burn,” said Paganel.

Mulrady shook his head doubtfully. “Fuel on the top of the Cordilleras?”

“Since there is a chimney in the casucha,” said the Major, “it’s likely that we can find something to burn in it.”

“Our friend MacNabbs is right,” said Glenarvan. “Get everything ready for supper, and I’ll go out and turn lumberjack.”

“Wilson and I will go with you,” said Paganel.

“Do you want me?” asked Robert, getting up.

“No, my brave boy, rest yourself,” said Glenarvan. “You’ll be a man, when older people are still children.”

Glenarvan, Paganel, and Wilson left the casucha. It was six o’clock in the evening. In spite of the perfect calmness of the air, the cold was stinging. The blue of the sky was already darkening, and high peaks of the Andes mountains were lit by the last rays of the setting sun. Paganel, had brought his barometer; consulting it showed 495 millimetres of mercury. This corresponded to an elevation of 11,700 feet.2 This region of the Cordilleras had an elevation only 4,100 feet3 lower than Mont Blanc. But if these mountains had the hazards with which the giant of Switzerland is bristling, if its blizzards had been unleashed against them, not one of the travellers would have survived the crossing of the great mountain chain of the New World.

On reaching a little mound of porphyry, Glenarvan and Paganel stopped to gaze about them and scan the horizon on all sides. They were now at the summit of the Cordilleras, and overlooked an area of 400 square miles4. To the east, the slopes descended in gentle ramps down which the peons would slide for several hundred yards at a time. In the distance, longitudinal streaks of stone and erratic blocks, pushed back by the sliding glaciers, formed immense lines of moraines. The valley of the Colorado was already lost in shadows from the setting sun. The relief of the ground, the projections of peaks and spires were disappearing as night was fast drawing her mantle over the eastern slopes of the Andes. The buttresses that supported the sheer walls of the western flanks of the mountains were illumined by the rays of the setting sun; the peaks and glaciers bathed in its radiance were a dazzling sight. Toward the north rippled a confusion of summits which blended together, like a trembling line drawn by an incompetent artist. But to the south the view was magnificent, and with the fading light, it was becoming more so. Across the wild valley of the Torbido, about two miles away, rose the volcano of Antuco. The mountain roared like the leviathan of Revelation, and vomited fiery smoke, mixed with torrents of sooty flame. The surrounding peaks appeared to be on fire. Showers of incandescent stones, clouds of reddish vapour and rockets of lava combined into sparkling streams. The apparent brightness increased from moment to moment, as daylight faded. A dazzling explosion filled this vast arena with its intense reverberations, while the sun, gradually stripped of its crepuscular rays, disappeared like a star extinguished in the shadows of the horizon.

Paganel and Glenarvan would have remained for a long time gazing at the magnificent struggle between the fires of earth and heaven if the more practical Wilson had not reminded them of the business at hand. There was no wood to be found, but the rocks were covered with a thin, dry species of lichen. They collected enough of this, as well as of a plant called yareta, whose root burns reasonably well. They brought this precious fuel back to the casucha and heaped it upon the hearth. The fire was difficult to light, and more difficult to keep burning. The air was so rarefied that there was scarcely enough oxygen in it to support combustion. At least, this was the reason assigned by the Major.

“On the other hand,” he added, “water will not need to be heated to one hundred degrees to boil. Those that want their coffee that hot will have to do without. At this height, water will boil at less than ninety degrees.”5

MacNabbs was right, as the thermometer proved, for it was plunged into the kettle when the water boiled, and the mercury only rose to 87. Coffee was soon ready, and eagerly gulped down by everyone. The dry meat seemed poor fare, and Paganel couldn’t help making a reasonable, yet impractical comment on it.

“Parbleu,” he said, “I wouldn’t mind some grilled llama. They say that llama is a good substitute for beef or mutton, and I would like learn if it is so for myself.”

“You’re not content with your supper, most learned Paganel?” asked the Major

“Enchanted with it, my brave Major; still I must confess I should not say ‘no’ to a dish of llama.”

“You are a sybarite.”

“Guilty as charged. But I’m sure that whatever you say, you wouldn’t object to a beefsteak yourself, would you?”

“Probably not.”

“And if you were asked to stand on watch all night in the cold and the darkness, you would do it without thinking?”

“Of course, if you want me to…”

MacNabbs’ companions had hardly time to thank him for his obliging good nature, when distant howls were heard. They went on for a long time, and were not the cries of a few animals, but those of an entire herd, approaching quickly. Paganel wondered if Providence was about to supply them with supper, after providing them with the hut. Glenarvan damped his optimism by pointing out that the herds of the Cordillera never ventured this high.

“Then where does the noise come from?” asked Tom Austin. “Don’t you hear them getting nearer!”

“An avalanche?” suggested Mulrady.

“Impossible,” said Paganel. “Those are real cries of animals.”

“Come,” said Glenarvan.

“And let’s go hunting,” said MacNabbs, who took his rifle.

They all rushed out of the casucha. Night had completely set in, dark and starry. The moon, now in her last quarter, had not yet risen. The peaks on the north and east had disappeared from view, and nothing was visible save the fantastic silhouette of some towering rocks here and there. The wails, clearly the cries of terrified animals, were redoubled. They came from the dark part of the Cordilleras. What could be going on there? Suddenly a furious avalanche arrived, an avalanche of living animals mad with fear. The whole plateau seemed to tremble. There were hundreds, perhaps thousands, of these animals, and in spite of the rarefied atmosphere, their noise was deafening. Were they wild beasts from the Pampas, or herds of llamas and vicuñas? Glenarvan, MacNabbs, Robert, Austin, and the two sailors just had time to throw themselves flat on the ground before the living whirlwind swept a few feet over them. Paganel, who, as a nyctalope, had remained standing to see better, was knocked down in the twinkling of an eye.

At the same moment the report of a firearm was heard. The Major had fired, and it seemed to him that an animal had fallen close by, while the whole herd, yelling louder than ever, had disappeared down the slopes lit by the reverberations of the volcano.

“Ah, I’ve got them,” said a voice: the voice of Paganel.

“Got what?” asked Glenarvan.

“My spectacles, parbleu! I wouldn’t have cared to lose them after such a tumult as this.”

“Are you hurt?”

“No, a little trampled, but by what?”

“By this,” said the Major, dragging the animal he had shot behind him.

They all hastened eagerly into the hut, to examine MacNabbs’ prize by the light of the fire.

It was a pretty creature, like a small camel without a hump. The head was small and the body flattened, the legs were long and slender, the skin fine, and the hair the colour of café au lait. The underside of its belly was spotted with white.

Paganel barely glanced at it. “A guanaco!”

“What sort of beast is a guanaco?” asked Glenarvan.

“One you can eat,” said Paganel.

“Is it good?”

“Tasty! A meal from Olympus! I knew we would have fresh meat for dinner, and such meat! But who is going to butcher the beast?”

“I will,” said Wilson.

“Then I will grill it,” said Paganel.

“Are you a cook, Monsieur Paganel?” asked Robert.

“Parbleu, my boy. I am French, and in every Frenchman there is always a cook.”

Five minutes later Paganel began to grill large slices of venison on the coals produced by the yareta’s root. Ten minutes later he served up to his companions this very appetizing meat, under the name of “guanaco cutlets.” No one stood on ceremony, but fell to with a hearty good will.

To the absolute stupefaction of the geographer, however, the first mouthful was greeted with a general grimace, accompanied by a “pouah!”

This was followed by a chorus of “It is horrible!” “It’s inedible!”

The poor scientist, whatever may be, was obliged to admit that this barbecue could not be enjoyed, even by hungry men. They began to banter about his “Olympian dish,” and indulge in jokes at his expense, which he did not contradict. All he cared about was to find out how it was that the flesh of the guanaco — which was reputed to be such good and edible food — had turned out so badly in his hands, when a sudden thought occurred to him.

“Eh parbleu!” he cried. “Of course! I have it!”

“The meat was too old, was it?” asked MacNabbs, quietly.

“No, parochial Major, but the meat had worked too much. How could I have forgotten that?”

“What do you mean?” asked Tom Austin.

“I mean this that the guanaco is only good for eating when it is killed in a state of rest. If it has been long hunted, and run a long way before it is captured, it is no longer edible. I can affirm the fact by the mere taste, that this animal has come a great distance, and consequently the whole herd has.”

“You are certain of this?” asked Glenarvan.

“Absolutely certain.”

“But what could have frightened the creatures so, and driven them from their haunts, when they ought to have been quietly sleeping?”

“That is a question, my dear Glenarvan, I could not possibly answer. Take my advice, and let us go to sleep without troubling our heads about it. For my part, I am very tired. I say, Major, shall we go to sleep?”

“Yes, we’ll go to sleep, Paganel.”

Each one, thereupon, wrapped himself up in his poncho, and the fire was banked for the night. Loud snores in every tune and key soon resounded from all sides of the hut, the deep bass contribution of Paganel completing the harmony.

But Glenarvan could not sleep. Uneasiness kept him in a continual state of wakefulness. His thoughts reverted involuntarily to those frightened animals flying in one common direction, impelled by one common terror. They could not be pursued by wild beasts, for at such an elevation there were scarcely any, and of hunters still fewer. What terror could have driven them toward Antuco’s abysses? Glenarvan felt a premonition of approaching danger.

But gradually he fell into a half-sleeping state, and his fears gave way to hope. He saw himself on the morrow on the plains of the Andes, where the search would actually commence, and perhaps success was close at hand. He thought of Captain Grant and his two sailors, and their deliverance from cruel bondage. As these images passed rapidly through his mind, every now and then he was roused by the crackling of the fire, or sparks flying out, or some little jet of flame would suddenly flare up and illuminate the faces of his slumbering companions. Then his premonitions came back with more intensity, and he listened anxiously to the sounds outside the hut.

At times he thought he could hear distant growls, rumbling noises in the distance, dull and threatening like the mutterings of thunder before a storm. Here, those sounds could only be a storm raging down below at the foot of the mountains. He got up and went out to see.

The moon was rising. The air was pure and calm. Not a cloud visible either above or below. Here and there was a passing reflection from the flames of Antuco, but there was neither storm nor lightning, and myriads of bright stars glittered overhead. Still the rumbling noises continued. They seemed to be getting closer and running through the Andean range. Glenarvan returned to the casucha more worried than ever, wondering what the connection could be between these sounds and the flight of the guanacos. He looked at his watch and found it was about two o’clock. Not being certain of any immediate danger, he did not wake his companions, whom fatigue held fast asleep, and after a little, dozed off himself, and slumbered heavily for some hours.

A violent crash made him start to his feet, a deafening noise like the roar of artillery. He felt the ground giving way beneath him, and the casucha rocked, and crumbled around them.

He shouted to his companions, but they were already awake, and tumbling pell-mell over each other to escape the collapsing hut. They were being rapidly drawn down a steep slope. Day dawned and revealed a terrible scene. The shape of the mountains was changing. Cones were cut off. Tottering peaks disappeared as if some hatch had opened under their base. Because of a peculiar phenomenon of the Cordilleras,6 a massif, many miles wide, had been displaced entirely, and was sliding down toward the plain.

“An earthquake!” yelled Paganel.

The plateau rushed down the slope with the speed of an express

He was not wrong. It was one of those frequent cataclysms on the mountainous edge of Chile. It was in this region where Copiapó had been destroyed twice, and Santiago laid in ruins four times in fourteen years. This region of the globe is so underlaid with volcanic fires, and the volcanoes in this chain insufficient safety valves for the subterranean vapours, that shocks known as tremblores are a frequent occurrence.

The plateau to which the seven stunned and terrified men were clinging, holding on by tufts of lichen, was rushing down the slope with the swiftness of an express, at the rate of fifty miles an hour. Not a cry was possible, nor an attempt to get off or stop. They could not even have heard themselves scream. The internal rumblings, the crash of the avalanches, the clash of masses of granite and basalt, and the whirlwind of pulverized snow, made all communication impossible. Sometimes the massif went perfectly smoothly without jolts or jerks; sometimes it would reel and roll like a ship in a storm. It ran alongside abysses into which fragments of the plateau fell away. It tore up trees by the roots, and levelled, with the precision of an immense scythe, every projection of the eastern slope.

One wonders at the power of a mass weighing several billion tons, hurtling with ever-increasing speed down a slope at an angle of fifty degrees.

How long this indescribable descent would last, no one could calculate; nor what abyss it ultimately would end in. None of the party knew whether all the rest were still alive, or whether one or another were already lying in the depths of some abyss. Stunned by the speed of the descent, frozen by the cold air which pierced through their clothing, blinded with the whirling snow, they gasped for breath. Exhausted and nearly unconscious, they clung to the rocks by a powerful instinct of self-preservation.

The Major picked himself up

A shock of incomparable violence suddenly tore them from their grip on their slippery vehicle. They were thrown forward and rolled to a stop at the foot of the mountain. The plateau had stopped dead.

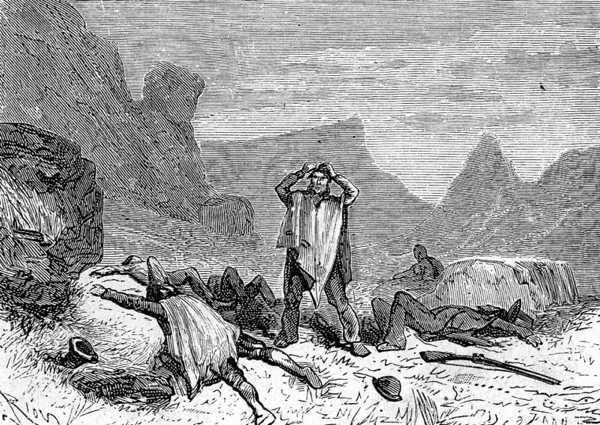

For some minutes no one stirred. At last one picked himself up, and stood on his feet, stunned by the shock, but still firm on his legs: the Major. He shook off the dust that blinded him and looked around. His companions lay in a close circle like the lead pellets from a shotgun, piled one on top of another.

The Major counted them. All except one lay on the ground around him. The one missing was Robert Grant.

1. 14° Fahrenheit — DAS

2. 3,570 metres — DAS

3. 1,250 metres — DAS

Verne’s original French text has them 910 metres below the elevation of Mont Blanc. I adjusted the numbers to make them consistent with the true height of that mountain. — DAS

4. Verne has 40 square miles, but you can see that large an area from on top of a small hill. — DAS

5. The boiling point of water lowers by about 1 degree for every 325 metres of elevation.

6. An almost identical phenomenon occurred on the flanks of Mont Blanc in 1820, in a terrible disaster that killed three guides from Chamonix.

Verne appears to be referring to the Hamel Accident, of 1820 which killed three climbers on Mont Blanc in an avalanche with very little resemblance to what he describes happening to the Glenarvan party — DAS.