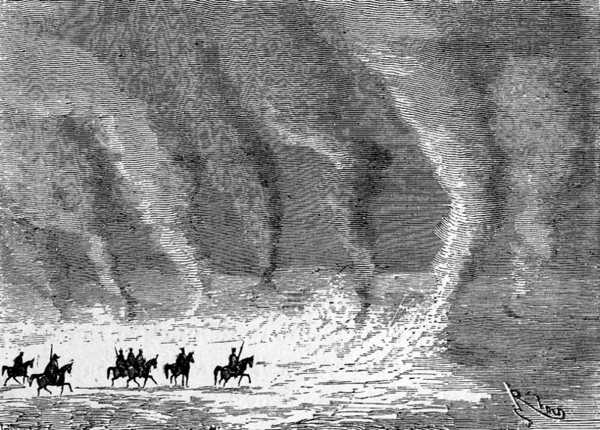

Dust-devils of the medanos

Next day, the 22nd of October, at eight o’clock in the morning, Thalcave gave the signal for departure. Between the 22nd and 42nd degrees the Argentinian ground slopes eastward, and all the travellers had to do was to follow the gentle incline down to the sea.

When the Patagonian had refused Glenarvan’s offer of a horse, he had supposed that it was because Thalcave preferred to walk, as some guides do, but this turned out not to be the case.

When they were ready to set out the Patagonian gave a peculiar hissing whistle, and a magnificent Argentinian bay mare1 came bounding out of a grove close by. The animal was a perfect beauty; proud; brave and spirited; her lively head tossed, her nostrils flared, her eyes were bright; she had wide legs, good withers, a high chest, and long pasterns: all the qualities that make for strength and flexibility in a horse. The Major, a connoisseur of horses, admired this specimen of the Pampean breed without reservation, and considered that, in many respects, it greatly resembled an English hunter. This splendid creature was named “Thaouka,” which means “bird” in Patagonian, and she was well named.

When Thalcave was in the saddle, his horse leaped beneath him. The Patagonian was a consummate rider, magnificent to see. His recado saddle had two of the hunting weapons commonly used on the Argentinian plains mounted to it: the bolas and the lasso. The bolas consists of three balls fastened together by a leather strap, attached to the front of the recado. The Indians will often fling it a hundred paces or more at an animal or enemy they are pursuing, and with such precision that they wrap around their legs and knock them down in an instant. It is a formidable weapon, that they handle with surpassing skill. The lasso on the other hand, is always retained in the hand. It is simply a rope, thirty feet long, made of tightly twisted leather, with a slip knot at the end, which passes through an iron ring. This noose was thrown with the right hand, while the left holds the rope, the other end of the rope is fastened to the saddle. A long rifle, with a shoulder strap completed the weapons of the Patagonian.

Thalcave, without noticing the admiration produced by his natural grace, his ease, and his proud carelessness, took the head of the troop. They set off, sometimes going at a gallop, sometimes a walk, for the trot seemed to be unknown to these horses. Robert proved to be a bold rider, and completely reassured Glenarvan as to his ability to keep his seat.

The Pampas begin at the very foot of the Cordilleras. They can be divided into three parts. The first extends from the chain of the Andes, and stretches 250 miles covered with low trees and bushes; the second 450 miles is clothed with magnificent grasslands, and stops about 180 miles from Buenos Aires; The third part of the Pampas stretches from this point to the sea, where the traveller’s footsteps trod over immense prairies of alfalfa and thistles.

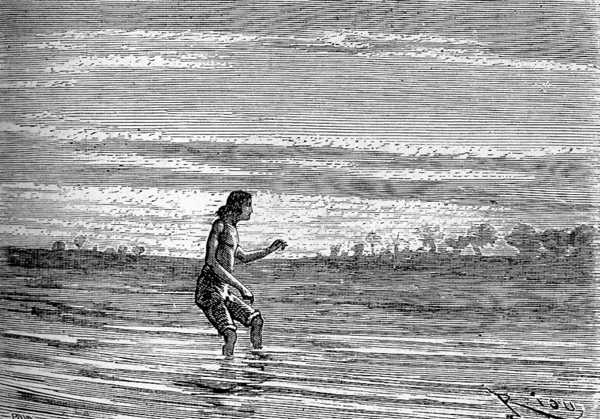

Dust-devils of the medanos

On leaving the gorges of the Cordilleras, Glenarvan and his band first encountered plains of sand dunes, called medanos, lying in ridges like waves on the sea, and moving with the wind where not secured by the roots of plants. The sand was so extremely fine that the slightest breeze picked up the light particles, and sent them flying in clouds that rose in dust-devils of considerable height. It was a spectacle which caused both pleasure and pain for the eyes. Nothing could be more extraordinary than to see these whirlwinds wandering over the plain, colliding and mingling with each other, or falling and rising in wild confusion. On the other hand, nothing could be more disagreeable than the dust which was thrown off of these innumerable medanos, which was so fine that it even found its way through closed eyelids.

This phenomenon lasted the greater part of the day, driven by a strong north wind. Nevertheless, they made good progress, and by six o’clock the Cordilleras lay a full forty miles behind them, their dark outlines almost lost in the evening mists.

They were all somewhat fatigued with the journey, and glad enough to halt for the night on the banks of the Rio Neuquén, a troubled torrent flowing between high red cliffs. The Neuquén is called Ramid, or Comoe by certain geographers and its source was known only to the Indians.

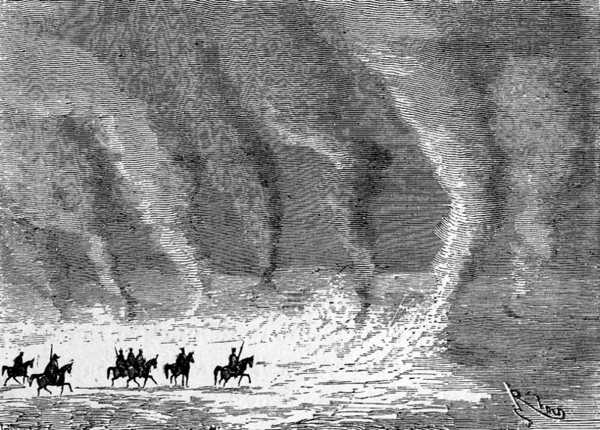

They rode quickly over the firm ground

That night, and the next morning passed without any noteworthy incidents. They rode well and fast. The firm ground, and moderate temperature made for trouble-free progress. The afternoon grew warmer, the sun’s rays became scorching, and when evening came, a bar of clouds streaked the southwestern horizon, a symptom of a change in the weather. The Patagonian pointed it out to the geographer.

“Yes, I know,” said Paganel. He turned to his companions. “See, a change of weather is coming! We are going to have a taste of pampero.”

He explained that this pampero is very common in the Argentinian plains. It is an extremely dry southwest wind.

Thalcave was right, for the pampero blew violently all night, making things very uncomfortable for men sheltered only by their ponchos. The horses lay on the ground, and the men stretched themselves beside them in a close group. Glenarvan was afraid they would be delayed if this hurricane continued, but Paganel reassured him, after consulting his barometer.

“The pampero generally brings a storm which lasts three days, and may be always foretold by the depression of the mercury,” he said. “But when the barometer rises — and it is — all we should expect is a few violent blasts. So you can make your mind easy, my good friend; by sunrise the sky will be quite clear again.”

“You talk like a book, Paganel,” said Glenarvan.

“And I am one; and what’s more, you are welcome to browse through me whenever you like.”

The book was right. At one o’clock in the morning the wind calmed, and the weary men fell asleep. They awoke at daybreak, refreshed and invigorated. Paganel stretched and cracked his joints with a joyous noise like a puppy.

It was the 24th of October, and the tenth day since they had left Talcahuano. They were still ninety-three miles2 from the point where the Rio Colorado crosses the 37th parallel, about three days’ journey. Glenarvan kept a sharp lookout for any Indians, hoping to question them about Captain Grant through Thalcave, as Paganel was beginning to be able to communicate well enough with him. But the track they were following was little used by the natives. The Pampas roads between the Argentinian Republic and the Cordilleras were to the north of them. They also didn’t come across any wandering Indians or sedentary tribes living under the law of the caciques. If by chance some nomadic horseman came in sight in the distance, he fled quickly, not caring to talk with strangers. Such a troop must have seemed suspicious to anyone who ventured in the plain. Small bandit bands would consider a group of eight well armed and mounted men too dangerous to attempt to rob, and any lone honest traveller in these deserted lands would see them as potential bandits, so it was impossible to approach either honest men, or bandits. Glenarvan also would have preferred being at the head of a band of rastreadores3 if any conversation might begin with rifle shots.

However much, in the interests of his search, Glenarvan might have regretted the absence of Indians, an incident soon occurred which amply justified his interpretation of the document.

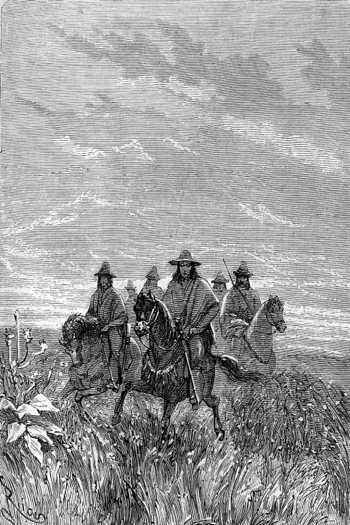

The road from Carmen to Mendoza

Several times the expedition’s route cut across other trails of the Pampas, among them the road from Carmen to Mendoza. The road was demarcated by the bones of domestic animals: mules, horses, sheep and oxen, that bordered it with their remains disintegrating under the beaks of birds of prey, and bleached by the sun. There were thousands of them, and no doubt more than a few human skeletons confusing their dust with the dust of the humblest animals.

Until then, Thalcave had made no observations on the route strictly followed by the party. He understood that the path they followed would not bring them in contact with any town, village, or settlement of the Argentinian Pampas. Every morning they set out straight toward the rising sun, travelled through the day without deviating from that line, and every evening the sun set directly to their west. It must have struck Thalcave that instead of being the guide he was the guided. If he was astonished by this, his natural reserve kept him from commenting on it, but on reaching this road, he stopped his horse.

“The Carmen road,” he said to Paganel.

“Yes, my brave Patagonian,” replied Paganel in his best Spanish. “the route from Carmen to Mendoza.”

“We are not going to take it?”

“No,” replied Paganel.

“Where are we going then?”

“Always to the east.”

“That’s going nowhere.”

“Who knows?”

Thalcave was silent, and gazed at the scientist with an air of profound surprise. He had no suspicion that Paganel was joking, for he was always serious, and it didn’t occur to him that others weren’t.

“You are not going to Carmen, then?” he added, after a moment’s pause.

“No.”

“Nor to Mendoza?”

“No, nor to Mendoza.”

Glenarvan came up to ask why they had stopped, and what Paganel and Thalcave were discussing.

“He wanted to know whether we were going to Carmen or Mendoza, and he is astonished at my negative reply to both questions.”

“Well, our route must seem odd, to him.”

“I think so. He says we’re not going anywhere.”

“Well, Paganel, could you not explain to him the object of our expedition, and why we are always going east.”

“That would be a difficult matter,” said Paganel, “for an Indian knows nothing about degrees, and the finding of the document would appear to him a mere fantastic story.”

“Is it the story he would not understand, or the storyteller?” asked MacNabbs, quietly.

“Ah, MacNabbs, I see you still have little faith in my Spanish.”

“Well, try it, my good friend.”

“So I will.”

Paganel returned to the Patagonian and began his narrative, frequently interrupted by the lack of words, by the difficulty of translating certain peculiarities, and by explaining to a half-ignorant savage details which were very difficult for him to understand. It was a curious sight. He gesticulated, he articulated, he struggled in a hundred ways, and big drops of sweat cascaded down his forehead onto his chest. When his tongue failed, his arms were called to aid. Paganel got down on the ground and traced a map on the sand, showing where the lines of latitude and longitude cross and where the two oceans were, where the Carmen road ran. Never was a teacher in such a quandary. Thalcave watched his antics calmly, without showing whether he understood or not. The geographer’s lesson lasted more than half an hour. When he came to the end of it, Paganel fell silent, mopped his face, which was dripping with sweat, and looked at the Patagonian.

“Does he understand?” asked Glenarvan.

“We will see,” said Paganel, “but if he doesn’t, I give up.”

Thalcave did not move. He did not speak. His eyes remained fixed on the lines drawn on the sand, now being erased by the wind.

“Well?” Paganel asked him.

Thalcave did not seem to hear him. Paganel could already see the ironic smile forming on the Major’s lips, and was about to recommence his geographical illustrations, when the Indian stopped him by a gesture.

“Looking for a prisoner?” he said.

“Yes,” replied Paganel.

“And just on this line between the setting and rising sun?” added Thalcave, pointing out by comparison with the Indian fashion the road from west to east.

“Yes, yes, that’s it.”

“And it is your God,” continued the guide, “that has sent you the secret of this prisoner on the waves of the vast sea?”

“God himself.”

“His will be done, then,” said Thalcave, solemnly. “We will march to the east, and if necessary, to the sun.”

Paganel, triumphing in his pupil, immediately translated Thalcave’s replies to his companions.

“What an intelligent race!” he said. “All my explanations would have been lost on nineteen in every twenty of the peasants in my own country.”

Glenarvan urged Paganel to ask the Patagonian if he had heard of any foreigners who had fallen into the hands of the Pampas Indians.

Paganel made the request, and awaited an answer.

“Maybe,” said the Patagonian.

At this word, Thalcave found himself surrounded by the seven travellers, questioning him with eager looks.

Paganel was so excited, he could hardly find words, and resumed his interrogation. He gazed at the grave Indian as if he could read the reply before it was spoken.

Each Spanish word spoken by Thalcave was instantly translated, so that the whole party seemed to hear him speak in their mother tongue.

“And what about the prisoner?” asked Paganel.

“He was a foreigner.”

“You have seen him?”

“No, but I have heard the Indians speak of him. He was a brave man. He had the heart of a bull.”

“The heart of a bull!” said Paganel. “Ah, this magnificent Patagonian language. You understand him, my friends, he means a courageous man.”

“My father!” exclaimed Robert Grant. “How do you say ‘It is my father.’ in Spanish?”

“Es mio padre,” replied the geographer.

Immediately taking Thalcave’s hands in his own, the boy said, in a soft voice:

“Es mio padre.”

“Suo padre,”4 replied the Patagonian, his face lighting up.

He took the child in his arms, lifted him up on his horse, and gazed at him with peculiar sympathy. His intelligent face was full of quiet feeling.

But Paganel still had many unanswered questions. “This prisoner, where was he? What was he doing? When did you hear of him?” All these questions poured out of him at once.

The answers were quick in coming, and Paganel learned that the European was a slave in one of the Indian tribes that roamed the country between the Colorado and the Rio Negro.

“But where was the last place he was in?”

“With the Cacique Calfoucoura.”

“In the line we have been following?”

“Yes.”

“And who is this Cacique?”

“The chief of the Poyuches Indians, a man with two tongues and two hearts.”

“That’s to say false in speech and false in action,” said Paganel, after he had translated this beautiful figure of the Patagonian language.

“And can we rescue our friend?” he added.

“Perhaps, if he is still in the hands of the Indians.”

“And when did you last hear of him?”

“A long while ago; the sun has brought two summers since then to the Pampas.”

Glenarvan’s joy could not be described. This reply agreed exactly with the date of the document. But one question still remained for him to put to Thalcave.

“You spoke of a prisoner,” said Paganel. “But were there not three?”

“I do not know,” said Thalcave.

“And you know nothing of his present situation?”

“Nothing.”

This ended the conversation. It was possible that the three men had become separated long ago. But what was known from the information given by the Patagonian was that the Indians spoke of a European who had fallen into their power. The date of his captivity, the place he was supposed to be, all the way to the Patagonian phrase used to express his courage, obviously applied to Captain Harry Grant.

The next day, the 25th of October, the travellers resumed their eastward journey with a fresh determination. The plain, always monotonous, formed one of those endless spaces which are called travesias in the language of the country. The clay soil was scoured smooth by the wind; not a stone, not even a pebble, rose above the level except in some arid and dry ravines, or on the edge of artificial pools dug by the Indians. Low forests, with black crowns pierced here and there by white carob trees whose pods contained a sweet, pleasant and refreshing pulp, appeared at long intervals. Sparse patches of terebinths, chanares, wild brooms, and all kinds of thorny trees whose thinness betrayed the infertility of the soil became more common.

The 26th was a long, tiring day. The travellers were determined to win the Rio Colorado. The horses, excited by their horsemen, made such an effort that by evening they reached the beautiful river of the Pampas, at 69° 45‘ of longitude. Its Indian name, the Cobu-Leubu, means “great river,” and after a long journey, it will empty into the Atlantic. There, at its mouth, a curious peculiarity occurs, for the volume of water in the river diminishes as it approaching the sea, either by soaking into the ground, or by evaporation, and the cause of this phenomenon is not yet determined.

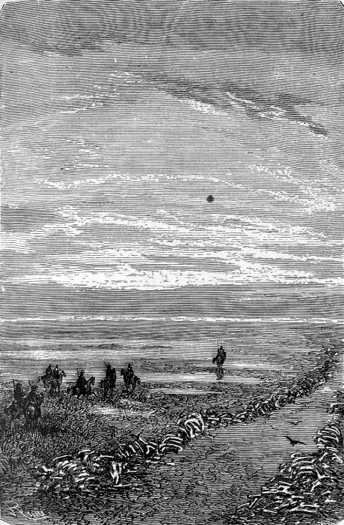

Paganel’s first ambition was to swim in its waters

Arriving at the Rio Colorado, Paganel’s first ambition was to swim “geographically” in its waters coloured by a reddish clay. He was surprised to find them so deep, still in flood from the melting mountain snow under the first summer sun. The river was too wide for the horses to swim across it. Fortunately, a few hundred yards upstream was a wicker bridge supported by leather straps and hanging in the Indian fashion. The little troop was able to cross the river and camp on the left bank.

Before falling asleep, Paganel took an exact measurement of the location of the Rio Colorado, and he marked it on his map with particular care, as a consolation for not finding the course of the Yarou-Dzangbo-Tchou, which flowed without him in the mountains of Tibet.

The next two days, the 27th and 28th of October, passed without incident. The land was monotonous, and sterile. Never was a landscape less varied, never more insignificant. The soil became very wet. It was necessary to pass canadas, kinds of flooded bottomlands, and esteros, permanent lagoons clogged with aquatic weeds. In the evening, the horses stopped at the edge of a large lake, with highly mineralized waters, the Ure-Lanquem, named “bitter lake” by the Indians, who in 1862 were witnessing cruel retaliation by Argentinian troops. They camped in the usual manner, and the night would have been good, but for the presence of alouatta monkeys5 and wild dogs. These noisy animals, no doubt in their honour, but certainly to the annoyance of European ears, performed one of those natural symphonies which would not have been disowned by a composer of the future.

1. A bit farther on Google will use “her” when referring to Thaouka, so I stuck “mare” in here. Even farther on I figured out that Google had made one of its mistakes, but decided to keep this change, and will continue referring to Thaouka as female.

2. 150 kilometres.

3. Raiders of the plain.

4. Your father.

5. Howler monkey.