They stopped at an abandoned rancho

The Argentinian Pampas extend from the 34th to the 40th degree of southern latitude. The word pampa, of Araucanían origin, means “grass plain”, and justly applies to the whole region. The mimosas growing on the western part, and the substantial grasslands on the eastern, give those plains a peculiar appearance. The vegetation is rooted in a layer of soil covering sandy red or yellow clay. The geologist would find rich treasures in the tertiary strata here, for it is full of antediluvian bones, which the Indians attribute to some extinct large armadillo species that lived in a past age, and been buried beneath layers of vegetable remains.

The South American Pampas are a geographical region similar to the African savannahs, or Siberian steppes. Its climate has more extremes of heat and cold than that of the province of Buenos Aires, being more continental. For, according to the explanation given by Paganel, the heat absorbed by the ocean in the summer is released during the winter, giving islands a more uniform temperature than the interior of continents.1 Because of this, the climate of the western Pampas does not have the consistency that it has on the coasts, thanks to the proximity of the Atlantic. It is subject to sudden excesses, and rapid changes, which constantly drive the thermometer from one extreme to the other. In autumn, during the months of April and May, torrential rains are frequent, but at this time of the year the weather was very dry and the temperature very warm.

They set off at dawn. Except for the road, itself, the soil of the region was held in place by shrubs and bushes. There were no medanos, nor the sand of which they were formed, nor the dust for the wind to suspend in the air. The horses went on at a good pace through the thick paja-brava, the pampas grass par excellence, so high and thick that the Indians find shelter in it from storms. The shallow basins were becoming rarer. These marshes were lined with willows, and Gynerium argenteum, a tall grass which thrived in the presence of fresh water. Here the horses drank their fill, taking the opportunity when it came. Thalcave went first to beat the bushes and frighten away the cholinas, a dangerous species of viper, whose bite will kill an ox in less than an hour. The agile Thaouka leapt over the undergrowth and helped her master clear a passage for the other horses.

They travelled quickly and easily over these boring and flat plains. No change occurred in the nature of the meadow; not a stone, nor pebble was seen for a hundred miles. It was the most monotonous landscape any of them had ever encountered, and it seemed to go on, and on. There was no change to the scenery, nor to anything found in it. You had to be a Paganel, one of those enthusiastic scientists who see wonders where there is nothing, to take interest in the details of this road. About what there was to excite him he could not explain. A bush, at most! A blade of grass, maybe. These sufficed to excite his inexhaustible enthusiasm, and to to give him something to teach Robert, who liked to listen to him.

On October 29th, the plain unfolded before the travellers with its infinite uniformity. About two o’clock, they came upon the remnants of a herd of oxen, their bones heaped up and bleached. The remains were not spread out in a winding line, such as such might be left by animals at the end of their strength and falling gradually on the path. Nobody knew how to explain this collection of skeletons in a relatively small space, neither Paganel, nor any of the others. He questioned Thalcave, who was able to answer him.

A “Pas possible!” from the scholar, and an emphatic affirmative sign from the Patagonian intrigued their companions.

“What is it?” they asked.

“The fire of Heaven,” replied the geographer.

“What? Lightning could have produced such a disaster?” said Tom Austin. “A herd of five hundred heads lying on the ground?”

“Thalcave affirms it, and Thalcave is a reliable witness. I believe it, moreover, because the storms of the Pampas are known to all for their fury. I hope we don’t encounter any!”

“It’s hot,” said Wilson.

“The thermometer,” said Paganel, “must mark thirty degrees in the shade.2

“It does not surprise me,” said Glenarvan; “I feel the heat penetrating me. I hope this temperature will not hold.”

“Oh, no!” said Paganel. “We must not count on a change of weather, since the horizon is free of all clouds.”

“Never mind,” replied Glenarvan, “for our horses are not much affected by the heat. You’re not too hot, boy?” he added, addressing Robert.

“No, My Lord,” replied the little fellow. “I like heat, it’s a good thing.”

“Especially in the winter,” the Major pointed out, blowing smoke from his cigar into the sky.

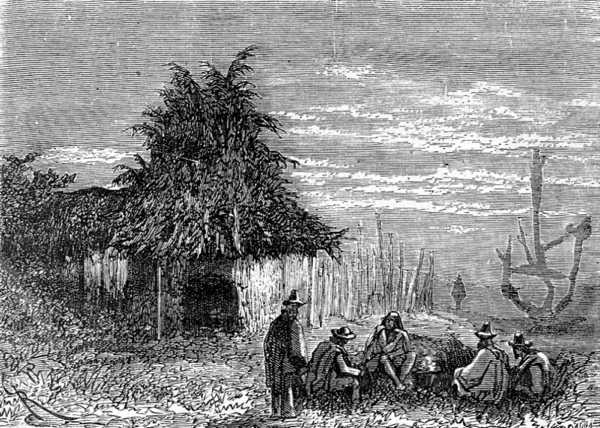

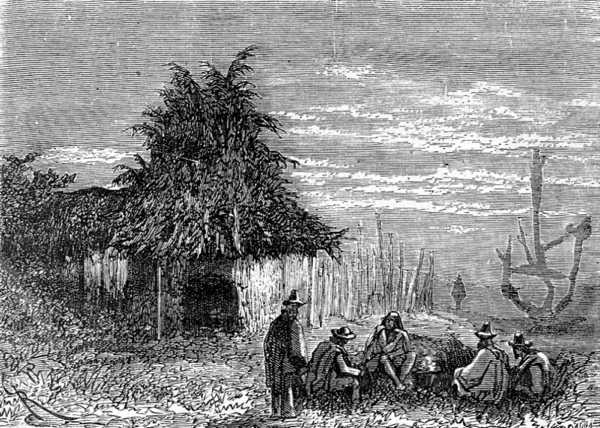

They stopped at an abandoned rancho

That evening, they stopped at an abandoned rancho, a wattle and daub hut roofed with thatch. This hut was beside an enclosure of half-rotten posts, which sufficed to protect the horses during the night against attacks from foxes. Not that they had anything to fear from these animals, but the malignant beasts gnawed their halters, and the horses would take advantage of that to escape.

There was a hole dug a few steps from the rancho that served as a kitchen and contained cold ashes from a fire. Inside, there was a bench, a leather pallet, a pot, a spit, and a maté kettle. Maté is a hot drink consumed in South America. It’s Indian tea. It consists of an infusion of fire-dried leaves, and is sucked up like American drinks, through a straw. At Paganel’s request, Thalcave prepared a few cups of this beverage, which was a very good accompaniment to their usual rations and was declared excellent.

The next day, October 30th, the sun rose in a fiery haze and poured its warming rays on the ground. The temperature rose quickly, and the plain offered no shelter. They resumed their eastward trek in spite of this. Several times they came across immense herds which, not having the strength to graze under this oppressive heat, remained lying lazily on the ground. These herds were guarded by dogs, which were accustomed to suckle the sheep when thirst prompted them. They watched, without supervision, these numerous herds of oxen, cows, and bulls. These animals had a mild humour, and do not have that instinctive horror of red which distinguishes their European cousins.

“It probably comes from grazing the grass of a republic!” said Paganel, delighted with his joke … a little too French perhaps.

Toward the middle of the day they couldn’t help but notice some changes occurring in the Pampas. Grasses became rarer. They gave way to meagre burdocks and gigantic thistles, nine feet high, which would have delighted all of the donkeys of the earth. Sparse plants sprouted here and there in the dry soil, stunted bushes and other thorny shrubs of a dark green. The clay of the grasslands had previously held enough moisture to maintain the thick and luxurious carpet of grass across the meadows, but now, this carpet was becoming worn and torn in many places, exposing the underlying weft, and spreading distress of the soil. These symptoms of increasing drought could not be ignored, and Thalcave pointed them out.

“I’m not sorry for this change,” said Austin. “All this grass, always grass; it becomes sickening in the long run.”

“Yes, but always grass, means always water,” said the Major.

“Oh, we are not short,” said Wilson, “and we will find some river on our way.”

If Paganel had heard this, he would not have failed to say that rivers were rare between Rio Colorado and the sierras of the Argentinian province; but at this moment he was explaining to Glenarvan a fact which had just caught his attention.

For some time, the atmosphere seemed to be imbued with a smell of smoke. However, no fire was visible on the horizon; no smoke betrayed a distant fire. Glenarvan could not therefore attribute a natural cause to this phenomenon. Soon the smell of burning grass became so strong that it astonished all the travellers, except Paganel and Thalcave. The geographer was, as always, quick to share his knowledge.

“We do not see the fire,” he said, “and yet we smell the smoke. Now, there’s no smoke without fire, and the proverb is as true in America as in Europe. So there is a fire somewhere. But these Pampas are so flat that nothing hinders the wind, and what we perceive is the smell of grasslands that burn at a distance of nearly seventy-five miles.3

“Seventy-five miles?” said the unconvinced Major.

“Or more,” said Paganel. “These conflagrations can spread quickly, and often cover vast areas.”

“Who sets fire to the meadows?” asked Robert.

“Sometimes lightning, when the grass is parched by heat; sometimes the Indians.”

“Why?”

“They claim — I do not know how well founded this claim is — that the pampas grasses grow better after a fire. It is a means of revitalizing the soil with the ashes. For my part, I believe that these fires are intended to destroy billions of ticks: parasitic insects that particularly inconvenience herds.”

“But this aggressive technique must cost the lives of some of the cattle that roam the plain,” said the Major.

“Yes, it burns a few; but what does that matter out of the multitudes?”

“I’m not worried about them,” said MacNabbs. “It’s their business, but it might be hard on travellers crossing the Pampas. What if they are surprised and enveloped by the flames?”

“Just so!” said Paganel, with an air of visible satisfaction. “It happens sometimes, and, for my part, I would not be sorry to see such a spectacle.”

“This is our learned man,” said Glenarvan. “He would follow science to the point of being burnt alive.”

“No, my dear Glenarvan, but I have read my Cooper, and Leatherstockings has taught us the means of stopping the spread of flames by tearing the grass around you within a radius of a few fathoms. Nothing is simpler. I do not fear the approach of a fire. I wish for it!”

But Paganel’s desires were not to be realized, and if he was half roasted, it was only in the heat of the sun’s rays, which poured down with an unbearable intensity. The horses were panting under the influence of this tropical temperature. There was no shadow to hope for, unless it came from some rare cloud veiling the burning disc; the shadow then ran on the level ground, and the horsemen, pushing their horses, tried to keep themselves in the shade which the westerly winds drove before them. But the horses would soon be left behind, and the unveiled star showered a new rain of fire on the parched ground of the Pampas.

When Wilson had said that their supply of water would not fail, he hadn’t counted on the unquenchable thirst that consumed his companions during that day. When he added that they would meet some river on the road, he had gone too far. In fact, there were no rivers, for the flatness of the terrain offered them no favourable bed. The artificial pools dug by the Indians were also dried up. Seeing the symptoms of drought increase from mile to mile, Paganel made these observations to Thalcave, and asked him where he expected to find water.

“At Laguna Epecuén4,” replied the Indian.

“And when shall we get there?”

“Tomorrow evening.”

When the Argentinians travel in the Pampas they generally dig wells, and find water a few feet below the surface. But the travellers could not fall back on this resource, not having the necessary tools. They were therefore obliged to husband the small provision of water they still had left, and deal it out in rations, so that no one became too thirsty, even if they couldn’t quench their thirst completely.

They halted that evening after travelling thirty miles and eagerly looked forward to a good night’s rest to compensate for the tiring day. But their slumbers were invaded by swarms of mosquitoes and gnats, which gave them no peace. They came with a change of the wind which had shifted to the north. These accursed insects generally disappeared with a south or southwest breeze.

Even these petty ills of life could not ruffle the Major’s equanimity, but Paganel was indignant at this teasing of fate. He damned the insects desperately, and deplored the lack of some acid lotion which would have eased the itching of their bites. The Major did his best to console him by reminding him of the fact that they had only to put up with two species of insect, among the 300,000 naturalists count. Paganel would not be soothed, and awoke the next morning in a very bad temper.

Paganel was quite willing to start at daybreak, despite the unrestful night, for they had to get to Laguna Epecuén before sundown. The horses were tired and dying for water, and though their riders had stinted themselves for their sakes, still their ration was insufficient. The drought grew deeper, and the heat no less intolerable under the dusty breath of the north wind, a Pampas simoon.

There was a brief interruption this day to the monotony of the journey. Mulrady, who was in front of the others, rode hastily back to report the approach of a troop of Indians. The news was received with very different feelings by Glenarvan and Thalcave. Glenarvan was glad of the chance of gleaning some information about the Britannia shipwreck, while Thalcave was not very happy to find the nomadic prairie Indians in his path. He considered them plunderers and thieves, and only sought to avoid them. Following his orders, the little troop massed, and prepared their weapons.

The nomads were ten in number

The nomads soon came in sight, and the Patagonian was reassured at finding they were only ten in number. They came within a hundred yards, and stopped. This was near enough to observe them distinctly. They were natives of the Pampean race, which had been almost entirely swept away in 1833 by General Rosas. Tall in stature, with arched forehead and olive complexion. They were dressed in skins of guanacos or skunks, and carried twenty foot lances, knives, slings, bolas, and lassos, and, by their dexterity in the management of their horses, showed themselves to be skilful riders.

They appeared to have stopped for the purpose of holding a council with each other, for they shouted and gesticulated at a great rate. Glenarvan determined to go up to them; but he had not crossed two fathoms before the whole band wheeled around, and disappeared with incredible speed.

“The cowards!” exclaimed Paganel.

“They scampered off too quick for honest folks,” said MacNabbs.

“Who are these Indians, Thalcave?” asked Paganel.

“Gauchos.”

“Gauchos!” said Paganel. He turned to his companions. “We need not have been so much on our guard; there was nothing to fear.”

“How is that?” asked MacNabbs.

“Because the Gauchos are harmless peasants.”

“You believe that, Paganel?”

“Certainly I do. They took us for robbers, and fled.”

“I rather think they did not dare to attack us,” replied Glenarvan, much annoyed at not being able to enter into some sort of communication with those Indians, whatever they were.

“That’s my opinion too,” said the Major. “If I am not mistaken, instead of being harmless, the Gauchos are formidable out-and-out bandits.”

“The idea!” exclaimed Paganel, and forthwith commenced a lively discussion of this ethnological thesis — so lively that the Major became excited, and, quite contrary to his usual suavity, said bluntly:

“I believe you are wrong, Paganel.”

“Wrong?” replied Paganel.

“Yes. Thalcave took them for robbers, and he knows what he is talking about.”

“Well, Thalcave was mistaken this time,” retorted Paganel, somewhat sharply. “The Gauchos are agriculturists and shepherds, and nothing else, as I have stated in a pamphlet on the natives of the Pampas, written by me, which has attracted some notice.”

“Well, you have committed an error, that’s all, Monsieur Paganel.”

“What, Mr. MacNabbs? You tell me I have committed an error?”

“A distraction, if you like, which you can put among the errata in the next edition.”

Paganel, highly incensed at his geographical knowledge being brought in question, and even jested about, allowed his ill-humour to get the better of him.

“Know, sir,” he said, “that my books have no need of such errata!”

“Indeed! Well, on this occasion they have, at any rate,” replied MacNabbs, quite as obstinate as his opponent.

“Sir, I think you are very annoying today.”

“And I think you are very crabby.”

The disagreement was in danger of growing far out of proportion to its merit. Glenarvan thought it was high time to intervene.

“Come, now, there is no doubt that one of you is very annoying and the other is very crabby, and I must say I am surprised at both of you.”

The Patagonian, without understanding the cause, could see that the two friends were quarrelling. He began to smile.

“It’s the north wind,” he said quietly.

“The north wind?” exclaimed Paganel. “What’s the north wind got to do with it?”

“Ah, it is just that,” said Glenarvan. “It’s the north wind that has put you in a bad temper. I have heard that, in South America, the wind greatly irritates the nervous system.”

“By St. Patrick, Edward, you are right,” said the Major, laughing heartily.

But Paganel, his temper roused, would not give up the contest, and turned upon Glenarvan, resenting this jesting intervention.

“And so, My Lord, my nervous system is irritated?” he said.

“Yes, Paganel, it is the north wind — a wind which causes many a crime in the Pampas, as the tramontane does in the Campagna of Rome.”

“Crimes!” returned the geographer. “Do I look like a man who would commit crimes?”

“That’s not what I said.”

“Are you afraid that I want to assassinate you?”

“Well,” replied Glenarvan, bursting into an uncontrollable fit of laughter. “I wasn’t previously. Fortunately, the north wind lasts only one day!”

Everyone joined in Glenarvan’s laughter. Paganel, still in a pique, went on ahead, alone. A quarter of an hour later his normal good mood returned, and he didn’t think about it again.

At eight o’clock in the evening, Thalcave, who was considerably in advance of the rest, saw in the distance the much-desired laguna. A quarter of an hour later, the little troop descended the banks of Laguna Epecuén, but a grievous disappointment awaited them — the laguna was dried up.

1. The winters of Iceland are therefore milder than those of Lombardy.

2. 86 degrees Fahrenheit — DAS

3. Thirty leagues. (120 kilometres — DAS)

4. Verne has Lake Salinas, but that lake is several degrees north of the our hero’s path, and Laguna Epecuén matches his location and description almost perfectly — DAS)