“Amigos!” said the Patagonian

For two hours the ombú navigated the immense lake without reaching land. The flames which had been devouring it were gradually extinguished. The main danger of their frightful passage had disappeared. The Major went so far as to say that he should not be surprised if they were saved after all.

The direction of the current remained unchanged, always carrying them to the northeast. The profound darkness was illumined now and then by a parting flash of lightning. Paganel searched in vain for some landmark on the horizon. The storm was nearly over. The rain had given way to light mists, which a breath of wind dispersed. The heavy masses of cloud had separated, and now streaked the sky in long bands.

The ombú was carried quickly by the heedless current, as if some powerful locomotive engine was hidden in its trunk. It seemed possible that they might drift this way for days. However, at about three o’clock in the morning, the Major noticed that the roots were beginning to graze the ground occasionally. Tom Austin, with a long branch began sounding the depth, and it was getting shallower. Twenty minutes later, the ombú ran aground with a violent jolt.

“Land! land!” shouted Paganel, in a ringing tone.

The tips of the charred limbs had struck a hillock, and never were sailors more glad of a grounding; the bank was like a harbour to them.

Already Robert and Wilson had leaped onto the dry land. They howled with joy when they heard a well-known whistle. The gallop of a horse resounded over the plain, and the tall form of Thalcave emerged from the darkness.

“Thalcave!” cried Robert, and the others joined in with one voice.

“Amigos!” said the Patagonian

“Amigos!” said the Patagonian, who had been waiting for the travellers here in the same place where the current had landed him.

As he spoke he lifted up Robert in his arms, and hugged him to his breast, never imagining that Paganel was hanging on to him. A general and hearty hand-shaking followed, and everyone rejoiced at seeing their faithful guide again. Then the Patagonian led the way into the shed of a deserted estancia, where there was a good, blazing fire to warm them, and a substantial meal of fine, juicy slices of venison soon broiling, of which they did not leave a crumb. When their minds had calmed down a little, and they were able to reflect, none of them could believe that they had escaped this adventure of so many different dangers: the flood, fire, and formidable caimans of the Argentinian rivers.

Thalcave, in a few words, gave Paganel an account of himself since they parted, entirely ascribing his deliverance to his intrepid horse. Then Paganel tried to make him understand their new interpretation of the document, and the consequent hopes they were indulging. Whether the Indian actually understood his ingenious hypothesis was in question; but he saw that they were glad and confident, and that was enough for him.

As can easily be imagined, after their compulsory rest on the ombú, the travellers did not want to delay getting back on the road. At eight o’clock they set off. No means of transport being procurable so far south, they were compelled to walk. However, it was not more than forty miles1 that they had to go now, and Thaouka would not refuse to give a lift occasionally to a tired pedestrian, or two if need be. In thirty-six hours they might reach the shores of the Atlantic.

The low-lying tract of marshy ground, still under water, soon lay behind them, as Thalcave led them upward to the higher plains. Here the Argentinian territory resumed its monotonous appearance. A few clumps of trees, planted by European hands, might chance to be visible among the pasturage, but quite as rarely as in the Tandil and Tapalquem Sierras. The native trees are only found on the edge of long prairies and about Cape Corrientes.

Next day, though still fifteen miles distant, the proximity of the ocean was felt. The virazon, a peculiar wind which blows regularly half of the day and night, bowed the tall grasses. The thin soil supported scattered woods, small arboreal mimosas, acacia bushes and bouquets of curra-mabol. They had to skirt around some saline lagoons that shimmered like broken glass, but made walking difficult. They pushed on as quickly as possible, hoping to reach Lake Salado on the shores of the ocean. The travellers were all rather tired when, at eight o’clock in the evening, they saw the sand dunes, twenty yards high, which skirt the coast. Soon the long murmur of breaking waves reached their ears.

“The ocean!” exclaimed Paganel.

“Yes, the ocean!” said Thalcave.

The exhausted men forgot their fatigue, and ran up the dunes with surprising agility.

But it was getting quite dark already, and their eager gaze could discover no traces of the Duncan on the gloomy expanse of water.

“But she is there, for all that,” said Glenarvan, “waiting for us, and running along this coast.”

“We shall see her tomorrow,” said MacNabbs.

Tom Austin hailed the invisible yacht, but there was no response. The wind was very high and the sea rough. The clouds were scudding along from the west, and the spray of the waves dashed up even to the sand-hills. It was little wonder, then, if the Duncan was at the appointed rendezvous, that her lookout could neither hear nor make himself be heard. The coast offered no shelter. Neither bay nor cove, nor port; not so much as a creek. It consisted of long sand-banks which ran out into the sea, and were more dangerous to a ship than rocky shoals. The sand-banks raised the waves into high rolling breakers that could dash any grounded ship to pieces.

It was natural, then, that the Duncan would keep far away from such a coast. John Mangles was too prudent a captain to get too near. Tom Austin was of the opinion that she would keep five miles out.

The Major advised his impatient relative to resign himself to circumstances. Since there was no means of dispelling the darkness, what was the use of straining his eyes by vainly endeavouring to pierce through it.

The Major organized the night’s encampment sheltered by the dunes. They prepared and ate the last meal of their journey with their remaining provisions. Afterward, each, following the Major’s example, dug an improvised bed in a comfortable hole, and, bringing his huge sand blanket up to his chin, fell into a heavy sleep.

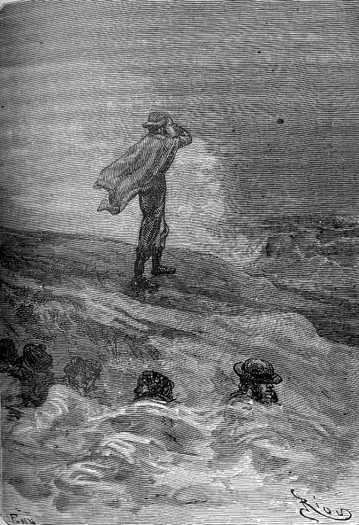

Glenarvan kept watch

But Glenarvan kept watch. There was still a stiff breeze, and the ocean had not yet settled from the recent storm. The waves broke upon the beach with a noise like thunder. Glenarvan could not rest, knowing the Duncan was so near him. It was unimaginable that she had not arrived at the appointed rendezvous. Glenarvan had left Talcahuano Bay on the 14th of October, and arrived on the shores of the Atlantic on the 12th of November. He had taken thirty days to cross Chile, the Cordilleras, the Pampas, and the Argentinian plains, giving the Duncan ample time to double Cape Horn, and arrive on the eastern coast. There was no conceivable delay that could have kept her away. Certainly the storm had been very violent, and its fury must have been terrible on such a vast battlefield as the Atlantic, but the yacht was a good ship, and the captain was a good sailor. She was bound to be there, and she would be there.

These reflections, however, did not calm Glenarvan. When the heart and reason are struggling, it is generally the heart that wins. The laird of Malcolm Castle felt all those he loved to be near in this darkness: his dear Helena, Mary Grant, the crew of his Duncan. He wandered up and down the lonely strand. He gazed, and listened, and even fancied he caught occasional glimpses of a faint light.

“I am not mistaken,” he said to himself; “I saw a ship’s light, one of the lights on the Duncan! Oh! why can’t I see in the dark?”

All at once the thought rushed across him that Paganel said he was a nyctalope, and could see at night. He went to go and wake him.

The scientist was sleeping as soundly as a mole in his hole when a strong arm pulled him up out of the sand.

“Qui va là?” he cried.

“It’s me.”

“Qui, vous?”

“Glenarvan. Come, I need your eyes.”

“My eyes?” Paganel tried to rub the sleep out of them.

“Yes, I need your eyes to make out the Duncan in this darkness, so come on.”

“Au diable with the nyctalopia!” Paganel muttered to himself, though he was pleased to be of any service to his friend.

He got up, shook his stiffened limbs, and stretching and yawning as most people do when roused from sleep, followed Glenarvan to the shore.

Glenarvan begged him to examine the distant horizon across the sea, which he did most conscientiously for some minutes.

“Well, do you see anything?” asked Glenarvan.

“Not a thing. Even a cat couldn’t see two paces in this darkness.”

“Look for a red light or a green one — her larboard or starboard light.”

“I see neither a red nor a green light, all is pitch dark.” Paganel’s eyes involuntarily began to close.

For half an hour he followed his impatient friend, mechanically letting his head frequently drop on his chest, and raising it again with a start. At last he neither answered nor spoke. His unsteady steps made him reel about like a drunken man. Glenarvan looked at him, and found he was asleep on his feet!

Glenarvan took him by the arm, and, without waking him, took him back to his hole, where he comfortably buried him.

At dawn, everyone was startled awake by a loud cry.

“The Duncan, the Duncan!” shouted Glenarvan.

They rushed to the shore, shouting “Hurrah, hurrah!”

There she was, five miles out, her lower sails carefully reefed, and her steam half up. Her smoke was lost in the morning mist. The sea was so rough that a vessel of her tonnage could not have ventured safely nearer the beach.

Glenarvan, armed with Paganel’s telescope, watched the Duncan’s progress. John Mangles had not yet seen them on the shore, for he did not alter his course, and continued to run, on port tack, under his topsails alone.

Thalcave fired his rifle, loaded with extra powder, in the direction of the yacht. They watched, and listened, but the Duncan gave no sign of having heard the shot. Thalcave fired a second, and third time. The reports of his gun echoed off the dunes.

At last a plume of white smoke was seen issuing from the side of the yacht.

“They see us!” cried Glenarvan. “That’s the Duncan’s gun.”

A few seconds later, a dull detonation came to die at the edge of the shore. The Duncan’s topsails were adjusted and the yacht came about, to come in as close to the shore as was safe.

Presently, through the glass, they saw a boat lowered.

“Lady Helena will not be able to come,” said Tom Austin. “It is too rough.”

“Nor John Mangles,” added MacNabbs; “he cannot leave the ship.”

“My sister, my sister!” cried Robert, stretching out his arms toward the yacht, which was now rolling violently.

“Oh, I can’t wait to get on board!” said Glenarvan.

“Patience, Edward! you will be there in a couple of hours,” replied the Major.

Two hours! But it was impossible for a boat, rowed with six oars, to make the return trip in a shorter space of time.

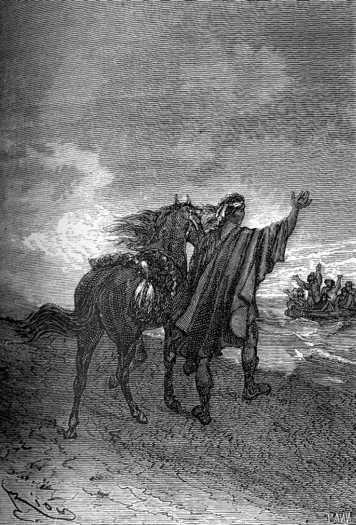

Glenarvan went back to Thalcave, who stood with his arms crossed beside Thaouka, calmly watching the waves.

Glenarvan took his hand, and pointing to the yacht, said “Come!”

The Indian gently shook his head.

“Come, friend,” said Glenarvan.

“No,” said Thalcave, softly. “Here is Thaouka, and there, the Pampas,” he added, embracing with a passionate gesture the wide-stretching prairies.

Glenarvan understood his refusal. He knew that the Indian would never forsake the prairie, where the bones of his fathers were whitening, and he knew the religious attachment of these sons of the desert for their native land. He therefore did not urge Thalcave longer, but simply squeezed his hand. Nor could he find it in his heart to insist, when the Indian, smiling as usual, would not accept the price of his services, pushing back the money, and saying:

“For friendship.”

Glenarvan could not reply; but he wished at least, to leave the brave Indian some souvenir of his European friends. What was there to give? Weapons, horses, he had lost everything in the disasters of the flood. His friends were no richer than him.

He was quite at a loss how to show his recognition of the selflessness of this noble guide, when an idea occurred to him. He drew from his wallet a precious medallion which surrounded an admirable portrait, a masterpiece of Lawrence, and he offered it to the Indian.

“My wife.”

The Indian gazed at it with a softened eye. “Good and beautiful,” he said.

Robert, Paganel, the Major, Tom Austin and the two sailors exchanged heartfelt farewells with the Patagonian. These good people were sincerely moved to leave this intrepid and devoted friend. Thalcave embraced them each, and pressed them to his broad chest. Paganel made him accept a map of South America and the two oceans, which he had often seen the Indian looking at with interest. It was the most precious thing the geographer possessed. As for Robert, he had only hugs to give, and these he lavished on his friend, not forgetting to give a share to Thaouka.

The boat from the Duncan was approaching, and in another minute had glided into a narrow channel between the sand-banks, and run ashore.

“My wife?” asked Glenarvan.

“My sister?” asked Robert.

“Lady Helena and Miss Grant are waiting for you on board,” replied the coxswain; “but we don’t have a minute to lose, Your Honour, for the tide is beginning to ebb.”

“Quien sabe?” said Thalcave

The last hugs were exchanged, and Thalcave accompanied his friends to the boat, which had been pushed back into the water. Just as Robert was going to step in, the Indian took him in his arms, and gazed tenderly into his face.

“Now go,” he said. “You are a man.”

“Goodbye, friend! Farewell” said Glenarvan, once more.

“Will we ever see each other again?” asked Paganel.

“Quien sabe?”2 said Thalcave, raising his arms to the sky.

Those were the Indian’s last words, dying away on the breeze. The boat pushed off. The boat moved away from the shore, carried by the receding tide.

For a long time, Thalcave’s dark, motionless silhouette stood out against the sky, through the white, dashing spray of the waves. Then by degrees his tall form began to diminish in size, until at last his friends lost sight of him, altogether.

An hour afterward Robert was the first to leap on board the Duncan. He flung his arms round Mary’s neck, amid the loud, joyous hurrahs of the crew on the yacht.

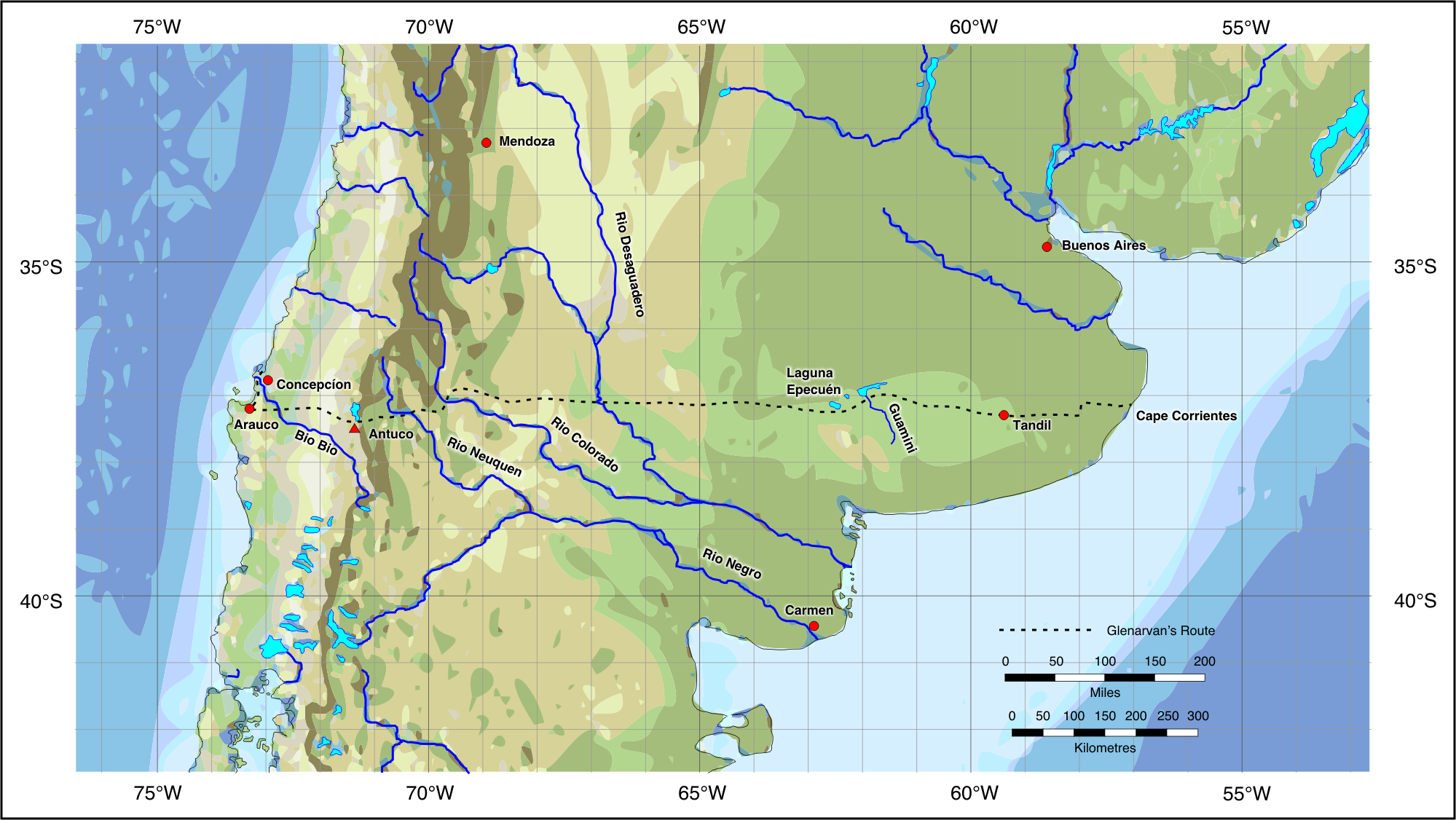

Thus the crossing of South America was accomplished, scrupulously following the 37th parallel. Neither mountains nor rivers had made the travellers change their course; and though they did not have to combat any ill-will from men, their determination had been roughly put to the test often enough by the fury of the unchained elements.

End of Book One

1. About fifteen leagues. (60 kilometres — DAS)

2. Who knows?

The searcher’s route across Chile and Argentina at the 37th parallel