The sun had just set behind the sparkling mists of the western horizon

Jacques Paganel’s story was applauded by everyone, but it didn’t change anyone’s opinion. They were in agreement on one point: they had to make do with their tree, as they had neither a palace, nor a hut.

The evening had advanced while they talked. All that remained for them to close out this eventful day was to get a good sleep. The guests of the ombú were not only tired by the ordeal of the flood, but overwhelmed by the heat of the day, which had been excessive. Their winged companions were already setting an example; the jilgueros, those nightingales of the Pampas, ceased their melodious roulades, and all the birds of the tree had disappeared into the the thick foliage. It was best to imitate them.

The sun had just set behind the sparkling mists of the western horizon

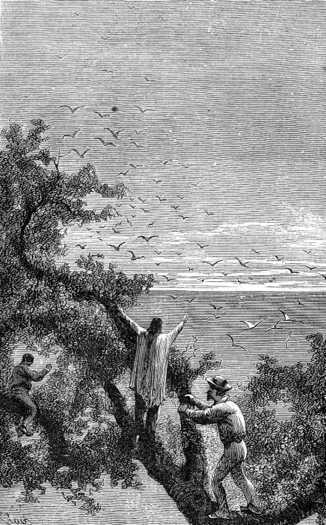

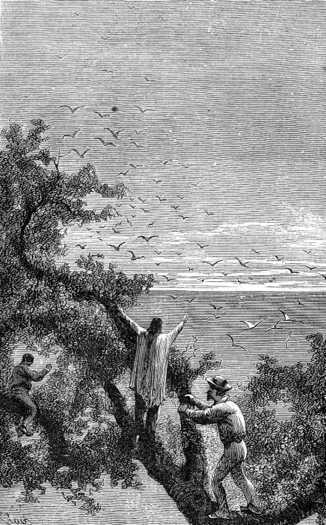

Before retiring “to their nest,” as Paganel had called it, he, Robert, and Glenarvan climbed up into his observatory to have one more inspection of the liquid plain. It was about nine o’clock; the sun had just set behind the sparkling mists of the western horizon. All this half of the celestial sphere, from the horizon to the zenith, was drowning in hot steam. The brilliant constellations of the southern hemisphere seemed veiled with light gauze, and were only partially visible. Nevertheless, they were distinct enough to be recognized, and Paganel pointed out the splendid stars of this circumpolar zone for the elucidation of Robert and Glenarvan. Among others, he showed them the Southern Cross, a group of four stars of first and second magnitude, arranged in rhombus, that orbited around the pole; the Centaur, where you could find the nearest star of the earth, 8,000 billion leagues away;1 the clouds of Magellan, two vast glowing nebulae, the largest of which covers an area two hundred times as large as the apparent size of the moon; then, finally, the “Coalsack”, a dark nebula where there seemed to be no stars at all, obscuring part of the Milky Way.

To his great regret, Orion, which can be seen from both hemispheres, had not yet risen; but Paganel taught his two pupils a curious peculiarity of Patagonian cosmography. In the eyes of the Indian poets, Orion represented an immense lasso and three bolas thrown by the hand of a hunter who traverses the celestial meadows. All these constellations, reflected in the mirror of the flood waters, were a beautiful sight, like a double sky surrounding them.

While Paganel discoursed on the stars, the eastern horizon was gradually assuming a most stormy aspect. A thick dark bar of cloud was rising higher and higher, and gradually extinguishing the stars. Before long half the sky was overspread. The cloud seemed to be advancing under its own power, for there was not a breath of wind. Absolute calm reigned in the atmosphere; not a leaf stirred on the tree, not a ripple disturbed the surface of the water. There seemed to be scarcely any air even, as though some vast pneumatic machine had rarefied it. High voltage electricity saturated the atmosphere, and every living thing felt it running along its nerves.

“We are going to have a storm,” said Paganel.

“You’re not afraid of thunder, are you, Robert?” asked Glenarvan.

“No, My Lord!”

“Good, the storm is not far off.”

“And a violent one, too,” added Paganel. “Judging by the look of things.”

“It is not the storm that worries me,” said Glenarvan, “so much as the torrents of rain that will accompany it. We shall be soaked to the skin. Whatever you may say, Paganel, a nest won’t do for a man, and you will learn that soon, to your cost.”

“With the help of philosophy, it will,” replied Paganel.

“Philosophy will not keep you from getting drenched.”

“No, but it will warm you.”

“Well,” said Glenarvan, “we had better go down to our friends, and advise them to wrap themselves up in their philosophy and their ponchos as tightly as possible, and above all, to lay in a stock of patience, for we shall need it before very long.”

Glenarvan gave a last glance at the threatening sky. The clouds now covered it entirely; only a dim streak of light from the setting sun shone faintly in the west. A dark shadow lay on the water, and it could hardly be distinguished from the thick vapours above it. There was no sensation of light or sound. All around was darkness and silence.

“Let us go down,” said Glenarvan. “The lightning will soon burst over us.”

On returning to the bottom of the tree, they found themselves, to their great surprise, in a sort of dim twilight, produced by myriads of luminous specks which appeared buzzing confusedly over the surface of the water.

“Phosphorescence?” said Glenarvan.

“No, but phosphorescent insects,” said Paganel. “A sort of glow-worm — living diamonds — which the ladies of Buenos Aires convert into magnificent ornaments.”

“What!” exclaimed Robert. “Those sparks flying about are insects!”

“Yes, my boy.”

Robert caught one in his hand, and found Paganel was right. It was a kind of large drone, an inch long, and the Indians call it “tuco-tuco.” This curious specimen of the Coleoptera sheds its radiance from two spots in the front of its breast-plate, and the light is sufficient to read by. Holding his watch close to the insect, Paganel saw distinctly that the time was 10 P. M.

On rejoining the Major and his three sailors, Glenarvan warned them of the approaching storm, and advised them to secure themselves in their beds of branches as firmly as possible, for there was no doubt that after the first clap of thunder the wind would become unchained, and the ombú would be violently shaken. Though they could not defend themselves from the waters above, they might at least keep out of the rushing current beneath.

They wished one another “good-night,” though without much hope for it, and then each one rolled himself in his poncho and lay down to sleep.

But the approach of a great phenomena of nature excites vague anxiety in the heart of every sentient being, even the strongest. The guests of the ombú felt agitated and oppressed, and not one of them could close his eyes. The first peal of thunder found them wide awake. They heard the first distant rumbling at about eleven o’clock. Glenarvan ventured to creep out of the sheltering foliage, and made his way to the extremity of the horizontal branch to take a look round.

The deep blackness of the night was already scarified with sharp bright lines, which were reflected back by the water with unerring exactness. The clouds had rent in many parts, but noiselessly, like some soft fluffy fabric. After observing both the zenith and horizon, which were merged in equal darkness, Glenarvan returned to the centre of the trunk.

“Well, Glenarvan, what’s your report?” asked Paganel.

“I say it is beginning in good earnest, and if it goes on so we shall have a terrible storm.”

“So much the better,” replied the enthusiastic Paganel. “I love a good show, since we can’t run away from it.”

“That’s another of your theories that will burst,” said the Major.

“And one of my best, MacNabbs. I am of Glenarvan’s opinion, that the storm will be superb. Just a minute ago, when I was trying to sleep, I recalled several facts to my memory that make me hope it will, for we are in the region of great electrical tempests. For instance, I have read somewhere, that in 1793, in this very province of Buenos Aires, lightning struck thirty-seven times during one single storm. My colleague, M. Martin de Moussy, counted fifty-five minutes of uninterrupted thunder.”

“Watch in hand?” asked the Major.

“Watch in hand,” said Paganel. “There is one thing that worries me — not that worrying will change anything — and that is that the culminating point of this plain is this very ombú where we are. A lightning rod would be very useful to us at present. For it is this tree especially, among all that grow in the Pampas, that the lightning has a particular affection for. Besides, I need not tell you, friend, that learned men tell us never to take refuge under trees during a storm.”

“Well,” said the Major, “It’s a little late to change that.”

“I must confess, Paganel,” added Glenarvan, “that you might have chosen a better time for this reassuring information.”

“Bah!” said Paganel. “Every moment is good for learning! Ha! Now it’s beginning.”

More violent bursts of thunder had interrupted this inopportune conversation. At first came the low grave rumbles like distant bass drums, but higher moderato snares soon joined in, accented with the crash of cymbals. The atmospheric strings added their strident accompaniment. The sky was on fire, and in this conflagration it was impossible to associate the reverberations of the thunder echoing across the sky to the electric flash of lightning that generated it.

The incessant flashes of lightning took various forms. Some darted down perpendicularly from the sky five or six times in the same place. Others would have thrilled the interest of any scholar, for though Arago, in his curious statistics, only cites two examples of forked lightning, it was visible here hundreds of times. Some of the flashes branched out in a thousand different directions, making coralliform zigzags, and threw out wonderful trees of light.

Soon the whole sky from east to north was underlined by a brilliant band of phosphorescence. This fire gradually spread over the entire horizon, igniting the clouds like a mass of combustible matter which was mirrored in the waters beneath. It formed an immense globe of fire, with the ombú at its centre.

Glenarvan and his companions gazed silently at this terrifying spectacle. They could not make their voices heard, but the sheets of white light which enwrapped them every now and then, revealed the face of one or another: sometimes the calm features of the Major; sometimes the eager, curious glance of Paganel; or the energetic face of Glenarvan; and at others, the frightened face of Robert, and the untroubled looks of the sailors, illuminated suddenly with spectral light.

As yet, no rain had fallen, and the wind had not risen in the least. But soon the cataracts of the sky opened, and vertical stripes stretched like the threads of a weaver against the black background of the sky. These large drops of water, striking the surface of the lake, were reflected in thousands of sparks illuminated by the fire of lightning.

A burning globe the size of a fist appeared at the end of the horizontal branch

Was the rain the finale of the storm? Would Glenarvan and his companions escape with nothing more than a vigorous shower? No. At the height of the struggle of the aerial fires, a burning globe, the size of a fist and surrounded by black smoke, suddenly appeared at the extremity of the horizontal branch. This ball, after spinning round and round for a few seconds, burst like a bombshell, and with so much noise that the explosion was distinctly audible above the general din. A sulphurous smoke filled the air, and complete silence reigned for a moment. It was broken by Tom Austin.

“The tree is on fire!” he shouted.

Tom was right. In a moment, as if some fireworks were being ignited, the fire ran along the west side of the ombú. The dead wood, nests of dried grass, and the spongy sapwood fed the hungry flames.

The wind rose, and fanned the flames. It was time to flee, and Glenarvan and his party hurried away to the eastern side of their refuge, which so far was untouched by the fire. They were all silent, troubled, and terrified as they watched branch after branch shrivel, and crack, and writhe in the flame like living serpents, and then drop into the swollen torrent, still red and gleaming, as it was borne swiftly away on the rapid current. The flames sometimes rose to a prodigious height, until they were lost in the conflagration of the atmosphere, and sometimes, beaten down by the hurricane, closely enveloped the ombú like a robe of Nessus. They were all terrified. A thick smoke suffocated them; an intolerable heat burned them; the fire gained on their side of the lower frame of the tree. Nothing could stop, or extinguish it! Finally, the situation was no longer tenable, and of the two deaths, it was necessary to choose the least cruel.

“Into the water!” yelled Glenarvan.

Wilson, who was nearest the flames, had already plunged into the lake, but next minute he screamed out in the most violent terror:

“Help! Help!”

Austin rushed to him, and with the assistance of the Major, dragged him back up onto the tree.

“What’s the matter?”

“Alligators! Alligators!” said Wilson.

The whole foot of the tree appeared to be surrounded by these formidable saurians. Their scales shimmered in the fire light; their tails vertically flattened, their heads like a spearhead, their eyes protruding, their jaws split as far as the back of the ear. The animals were instantly recognized by Paganel, as a ferocious species of alligator peculiar to America, called caimans in the Spanish territories. About ten of them lashed the water with their powerful tails, and attacked the ombú with the long teeth of their lower jaw.

At this sight the hapless men felt lost. A frightful death was in store for them. They must either be devoured by the fire or by the caimans.

Even the Major said, in a calm voice “This may well be the end for us.”

There are circumstances in which men are powerless, when the unchained elements can only be combated by other elements. Glenarvan’s haggard gaze shifted between the fire and the water leagued against him, hardly knowing what deliverance to implore from Heaven.

The violence of the storm had abated, but a considerable quantity of vapours had accumulated in the atmosphere, to which electricity was about to communicate immense force. In the south an enormous whirlwind, a cone of mists, was forming — the point at the bottom, and base at the top, which connected the turbulent water and the angry clouds. It soon began to move forward, spinning with terrifying speed, and sweeping up a column of lake water into its centre, while its whirling motion made all the surrounding currents of air rush toward it.

The gigantic water-spout threw itself on the ombú

A few seconds later the gigantic water-spout threw itself on the ombú, and caught it up in its whirl. The tree shook to its roots. Glenarvan could fancy the caimans’ teeth were tearing it up from the soil; for as he and his companions held on, each clinging firmly to the other, they felt the towering ombú give way, and fall. Its flaming branches plunged into the tumultuous water with a terrible hiss. It was over in an instant. Already the water-spout had passed, to carry on its destructive work elsewhere. And drawing its waters up as it went, it seemed to empty the lake in its passage.

The ombú lying in the water, began to drift rapidly along, impelled by wind and current. All the caimans had fled, except one that was crawling over the upturned roots, and coming toward the poor refugees with wide open jaws. But Mulrady, seizing hold of a branch that was half-burned off, struck the animal so hard that he broke its back. The caiman fell away into the eddies of the torrent.

Glenarvan and his companions — rescued from the voracious saurians — stationed themselves on the branches windward of the conflagration, while the ombú sailed along like a blazing fire-ship through the dark night, the flames spreading themselves like sails before the breath of the hurricane.

1. Close. The Alpha Centauri system is 4.37 light years from Earth, which is 10,300 billion leagues. Proxima Centauri — which had not yet been discovered, and is not visible to the naked eye — is slightly closer, at 10,000 billion leagues.