The conical peak of Tristan looked black against the bright sky

If the yacht had followed the line of the equator, the 196 degrees which separate Australia from America, or, more correctly, Cape Bernouilli from Cape Corrientes, would have been equal to 11,760 nautical miles1; but along the 37th parallel these same degrees, owing to the shape of the earth, only represent 9,480 nautical miles2. From the American coast to Tristan da Cunha is 2,100 miles3 — a distance which John Mangles hoped to cross in ten days, if east winds didn’t slow the yacht. But any worry on that score was soon allayed, for toward evening the breeze noticeably lulled and then changed, and the Duncan was able to display all her incomparable speed on a calm sea.

The passengers had resumed their ordinary shipboard life, and it hardly seemed as if they had been gone for a whole month. Instead of the Pacific, the Atlantic stretched itself out before them, and there was scarcely a shade of difference in the waves of the two oceans. The elements, after having handled them so roughly, now seemed to be uniting in their favour. The ocean was peaceful, and the wind was on the beam, so that the yacht could spread all her canvas, to lend its aid to the indefatigable steam stored up in the boiler.

The crossing was completed without incident or accident. The closer they came to Australia, the more their confidence grew. They began to talk of Captain Grant as if the yacht were going to take him on board at their Australian port of call. His cabin was prepared, and berths for his men. Mary delighted in arranging and decorating it with her own hands. It had been ceded to him by Mr. Olbinett, who was now sharing a cabin with his wife. This cabin was next to the famous number six, which Paganel had taken possession of instead of the one he had booked on the Scotia.

The learned geographer spent most of his time shut up in his cabin. He was working from morning till night on a work entitled Sublime Impressions of a Geographer in the Argentine Pampas. They could hear him repeating elegant phrases aloud before committing them to the white pages of his notebook; and more than once, unfaithful to Clio, the muse of history, he invoked in his transports the divine Calliope, the muse of epic poetry.

Paganel made no secret of it, either. The chaste daughters of Apollo willingly left the slopes of Helicon and Parnassus at his call. Lady Helena paid him sincere compliments on his mythological visitants, and so did the Major.

“But above all,” he added, “no distractions, my dear Paganel. And if by chance you take a fancy to learn Australian, don’t go and study it in a Chinese grammar!”

Things went smoothly on board. Lady Helena and Lord Glenarvan watched the growing attraction between John Mangles and Mary Grant with interest. There was nothing to be said against it, and, indeed, since John remained silent, it was best not to mention it to him, either.

“What will Captain Grant think?” Lord Glenarvan asked his wife one day.

“He will think that John is worthy of Mary, my dear Edward, and he’ll be right.”

The yacht was making rapid progress. Five days after losing sight of Cape Corrientes on the 16th of November, they fell in with fine westerly breezes, the very ones which take the ships which round the tip of Africa against the regular south-easterly winds. The Duncan covered herself with canvas, and under her foresail, brigantine, topsail and topgallant, studsails, jibs and stays, she ran on the port tack with daring speed. Her screw was barely biting the receding waters cut by her bow, as if she were running a race with the Royal Thames Yacht Club.

Next day, the ocean was covered with immense sea-weeds, looking like a vast pond choked with grass. It was one of those sargasso seas formed of the debris of trees and plants torn off the neighbouring continents that Commander Murray had described. The Duncan seemed to be gliding over a broad prairie, which Paganel compared to the Pampas, and her speed slackened a little.

Twenty-four hours later, at dawn, the man on the look-out was heard calling out “Land ho!”

“In what direction?” asked Tom Austin, who was on watch.

“Leeward!” said the sailor.

This excited cry had everyone popping up on deck. Soon a telescope made its appearance, followed immediately by Jacques Paganel.

The scientist pointed his instrument in the direction indicated, but could see nothing that resembled land.

“Look in the clouds,” said John Mangles.

“Ah,” said Paganel. “Now I do see it. A sort of peak, but very indistinctly.”

“It is Tristan da Cunha,” said John Mangles.

“Then if my memory serves me right, we must be eighty miles from it,” said Paganel. “For Tristan’s peak, seven thousand feet high, is visible at that distance.”

“Precisely,” said Captain John.

The conical peak of Tristan looked black against the bright sky

Some hours later, the sharp, lofty crags of the group of islands stood out clearly on the horizon. The conical peak of Tristan looked black against the bright sky which seemed all ablaze with the splendour of the rising sun. Soon the main island emerged from the rocky mass, its triangular peak inclining toward the north-east.

Tristan da Cunha is situated at 37° 8′ of southern latitude, and 10° 44′ of longitude west of the Greenwich meridian.4 Inaccessible Island is eighteen miles to the southwest, and Nightingale Island is ten miles to the southeast. They make up a solitary little group of islets in the Atlantic Ocean. Toward noon, the two principal landmarks which are used as recognition points by sailors were sighted: a rock, shaped like a ship under sail on Inaccessible Island, and two islets similar to a ruined fort at the northern point of Nightingale Island. At three o’clock the Duncan entered Falmouth Bay of Tristan da Cunha, that the tip of Bon-Secours point shelters from westerly winds.

A few whaling ships were lying quietly at anchor there, for the coast abounds in seals and other marine animals.

John Mangles’ first concern was to find good anchorage, for this bay is very vulnerable to northwest and northwesterly winds. It was at precisely this place that the English brig Julia was lost in 1829. The Duncan came to rest half a mile from shore, and anchored in twenty fathoms on a bed of rocks. All the passengers, both ladies and gentlemen, got into the long boat and were rowed ashore. They stepped out on a beach covered with fine black sand, the debris of the volcanic rocks of the island.

The capital of the Tristan da Cunha group consists of a little village overlooking the bay, on a large, murmuring brook. There were about fifty houses, quite clean, and arranged with the geometrical regularity which seems to be the last word in English architecture. Behind this miniature town lay 1,500 hectares of meadow, bounded by an embankment of lava. The conical peak rose 7,000 feet above this plateau.

Lord Glenarvan was received by a governor from the English colony at Cape Town. He inquired at once respecting Harry Grant and the Britannia, and found the names entirely unknown. The Tristan da Cunha Islands are out of the shipping lanes, and therefor rarely visited. Since the famous wreck of the Blendon Hall on the rocks of Inaccessible Island in 1821, two vessels have stranded on the main island — the Primanguet in 1845, and the American three-master Philadelphia in 1857. These three events comprise the whole catalogue of maritime disasters in the annals of the da Cunhas.

Lord Glenarvan had not expected to glean any more precise information, and only asked the governor for the sake of thoroughness. He even sent the boats to make the circuit of the island, the circumference of which was not more than twenty-five miles.5 London or Paris wouldn’t fit on the island, even if it were three times larger.

In the interim the passengers walked about the village and the neighbouring coast. The population didn’t exceed 150 inhabitants, and consisted of Englishmen and Americans, married to Hottentots from Cape Town, who leave nothing to be desired in terms of ugliness. The children of those heterogeneous households are very disagreeable compounds of Saxon stiffness and African darkness.

The tourists extended their promenade along the shore, glad to feel the firm ground beneath their feet. Wide spreading pastures stretched upward from the beach, the only part of the island which was cultivated. Everywhere else the coast was composed of steep, craggy, lava cliffs, where enormous albatrosses and stupid penguins congregated in hundreds of thousands.

The visitors, after examining the igneous rocks, went up to the plain. Sparkling, murmuring brooks ran here and there, fed by the eternal snows which crowned the cone. Green bushes on which the eye could count almost as many sparrows as flowers, enlivened the meadows. One species of tree, a kind of Phylica grew twenty feet high, and the Spartina arundinacea, or tussac grass, grew in large bamboo like clumps in the fertile pastures. Acaena, a low bush with reddish flowers and a fruit covered in barbs that clung to clothing, a few perennial shrubby plants whose balsamic scents filled the breeze with penetrating scents, mosses, wild celery, and ferns formed a small but opulent flora. Eternal spring seemed to smile on the island. Paganel enthusiastically maintained that this was the famous Ogygia sung of by Homer. He proposed that Lady Glenarvan should seek a grotto, like Calypso, and asked for no other use for himself than to be “one of the nymphs who served her.”

The party returned to the yacht at nightfall, talking, and admiring the natural riches displayed on all sides. Herds of cattle and sheep grazed in the neighbourhood of the village. Fields of wheat, maize, and vegetables, imported forty years before, spread their wealth to the edges of the capital.

The boats returned to the Duncan as Lord Glenarvan was coming back aboard. They had gone around the entire island in a few hours, without coming across a trace of the Britannia. The only result of this circumnavigation was to strike the name of Tristan Island from the search programme.

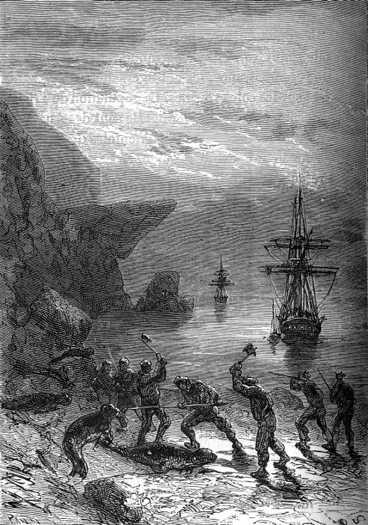

The Duncan could now leave these African Islands, and resume her course eastward. The reason that she did not set sail that same night was that Glenarvan had given permission to his crew to hunt the innumerable seals which, under the name of calves, lions, bears, and marine elephants, crowd the shores of Falmouth Bay. Right whales, too, were formerly very numerous about the island, but they have been chased and harpooned by so many ships’ crews, that scarcely any were left. Amphibious animals, on the other hand, gathered there in herds, and the crew of the yacht resolved to spend the whole night in hunting them, and to devote the next day to making a good supply of oil. So the Duncan’s departure was postponed until November 20th.

During supper, Paganel gave some interesting details about the Tristan Islands. He informed his listeners that the group was discovered in 1506 by a Portuguese mariner, named Tristão da Cunha, one of Albuquerque’s companions, but they remained unexplored for more than a century. These islands were believed, and not without reason, to be the nests of tempests, and had no better reputation than Bermuda. They were scarcely ever approached, and no ship landed there, unless driven by Atlantic gales.

In 1697, three Dutch ships of the East India Company stopped there, and determined their coordinates, leaving to the great astronomer Halley the task of reviewing their calculations in the year 1700. From 1712 to 1767, some French navigators became acquainted with them, and La Pérouse6 visited them during his famous voyage of 1785.

It was not until 1811, that an American, Jonathan Lambert, undertook to colonize them. He and two others landed there in the month of January, and courageously commenced their labours as colonists. The English governor of the Cape of Good Hope, hearing that they prospered, offered them the protection of England, which Jonathan accepted, and hoisted the British flag over his hut. He seemed to have reigned peacefully over his people, namely an old Italian and a Portuguese mulatto, until one day during a reconnaissance of the shores of his empire he either drowned himself or was drowned; it is not known which. Then came the year 1816, when Napoleon was imprisoned at St. Helena, and to guard him more securely, the English government placed a garrison on Ascension Island, and another on Tristan da Cunha. At Tristan the garrison consisted of a Cape artillery company and a detachment of Hottentots. In 1821, on the death of Napoleon, the troop was sent back to Cape Town.

“A solitary European, who was a corporal, and a Scot—”

“Ah, a Scot!” said the Major, always interested in his countrymen.

“His name was William Glass,” said Paganel, “and he remained alone on the island with his wife and two Hottentots. Not long afterwards, two Englishmen, a sailor and Thames fisherman, and an ex-dragoon in the Argentinian army, joined the little party, and, in 1821, one of the survivors of the shipwrecked Blendon Hall and his young wife took refuge on the island. This raised the number of inhabitants to six men and two women. In 1829, there were seven men, six women, and fourteen children. In 1835, the number rose to forty, and now the population is tripled.”

“So begin nations,” said Glenarvan.

“To complete the history of Tristan da Cunha, I will add that this island deserves to be called a Robinson Crusoe island as much as Juan Fernandez, for if two sailors were castaways successively on Juan Fernandez, two scholars narrowly escaped being left on Tristan da Cunha. In 1793, one of my countrymen, the naturalist Aubert Dupetit-Thouars, carried away by his passion for botanical research, lost himself, and only managed to rejoin his ship at the very moment the anchor was being lifted. In 1824, one of your compatriots, my dear Glenarvan, a skilful draughtsman, named Augustus Earle, was left on the island for eight months. The captain of his ship had forgotten he was on land, and sailed for Cape Town without him.”

“Well, that’s what I call an absent-minded captain,” said the Major. “Probably one of your parents, Paganel.”

“If he was not Major, he deserved to be!”

The Duncan’s crew had a good hunt

During the night the Duncan’s crew had such good hunting that upward of fifty large seals were caught; and as Glenarvan had authorized the hunt, he could not but allow his men to make the most of it. The following day was spent in dressing the skins, and in preparing the oil of the lucrative animals. The passengers used the day for a second excursion around the island. Glenarvan and the Major took their rifles with them in hopes of finding game. This walk extended to the foot of the mountain, on a soil strewn with broken rocks, slag, porous and black lava, and all sorts of volcanic detritus. The foot of the mountain was a chaos of tottering rocks. It was hard to mistake the nature of the enormous cone, and the English Captain Carmichael was right to recognize it as an extinct volcano.7

Several wild boars were seen by the hunters, one of which was shot by the Major. Glenarvan contented himself with killing a few brace of black partridges, which made an excellent salmis when cooked. A large number of goats were seen at the top of the high plateaus. Numerous feral cats, fierce, proud, powerful creatures, formidable even to dogs, promised one day to become very ferocious beasts.

At eight o’clock everyone returned on board, and during the night the Duncan set sail, and left the shores of Tristan da Cunha, never again to revisit them.

1. 5,450 leagues (21,800 kilometres — DAS)

2. 4,400 leagues (17,600 kilometres — DAS)

The Hetzel version seems to have goofed in its arithmetic again, giving incorrect distances in its footnotes. The distances given in nautical miles in the text is correct — DAS

3. 875 leagues (3,380 kilometres — DAS)

4. 13° 4′ west of the Paris meridian. The difference between these two meridians is 2° 20′.

5. Verne gives the island a circumference of only seventeen miles — DAS

6. Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse was a French naval officer and explorer, who vanished in the vicinity of the Solomon Islands, in 1788 — DAS

7. Not so extinct. The volcano on Tristan da Cunha last erupted in 1961, causing a two year evacuation of the island. An offshore eruption in 2004 nearly caused another evacuation — DAS