The little house where the three islanders lived was nestled in a natural harbour

As John Mangles intended to put in at the Cape of Good Hope for coal, he was obliged to deviate a little from the 37th parallel, and go two degrees north. The Duncan was south of the zone of the trade winds, and the strong westerlies sped her on her way1 In less than six days she cleared the 1,500 nautical miles2 which separate the tip of Africa from Tristan da Cunha, and on the 24th of November, at three o’clock, Table Mountain was sighted. At eight o’clock they entered the bay, and cast anchor in the port of Cape Town.

Paganel, as a member of the Society of Geography, could not ignore that the tip of Africa was first reached in 1486 by the Portuguese admiral Bartolomeu Dias, and doubled in 1497 by the famous Vasco De Gama. And how could Paganel have ignored it, since Camões sang of the glory of the great navigator in his Lusiades? But in this regard he made a curious remark: if Dias, in 1486, six years before the first voyage of Christopher Columbus, had doubled the Cape of Good Hope, the discovery of America might have been indefinitely delayed. The Cape Route was a shorter and more direct way to the East Indies. Columbus was seeking a route to the “Spice Islands,” so, once the Cape was doubled, his expedition would have been without purpose, and he might not have gone.

Cape Town, situated on Table Bay, was founded by the Dutchman Van Riebeck in 1652. It is the capital of an important colony which was ceded to the English by the Treaty of 1815. The passengers of the Duncan took advantage or their stop to go ashore. They had only twelve hours to spend on a walk, for one day was enough for Captain John to renew his supplies, and he wanted to leave on the morning of the 26th.

But this would be long enough to examine the chess-board of houses and streets, arranged with geometrical regularity known as Cape Town, where thirty thousand inhabitants — blacks and whites — enact the role of kings and queens, knights and pawns, and perhaps fools. At least that was Paganel’s opinion of it. When you have seen the Castle at the southeast of the town, the Government House and Garden, the Exchange, the Museum, and the Stone Cross erected by Bartolomeu Dias at the time of his discovery; and when you have drank a glass of Pontai, the first growth of the Constantia wines, it remains only to leave. This is what they did at dawn the next day. The Duncan sailed under her jib, staysail, foresail, and topsail, and a few hours later she doubled the famous Cape of Storms, to which the optimist King of Portugal, John II, gave the very inappropriate name of Bonne-Espérance.

Between the Cape and Amsterdam Island lie 2,900 miles3 of ocean, but with a good sea and favourable breeze, this was only a voyage of ten days. The elements were now no longer at war with the travellers, as they had been on their journey across the Pampas. Wind and sea seemed in league to help them forward.

“Ah! The sea! The sea!” said Paganel. “It is the field par excellence for the exercise of human energies, and the ship is the true vehicle of civilization. Think, my friends, if the globe had been only an immense continent, we would only know the thousandth part of it, even in this nineteenth century. See what is happening in the interiors of the great lands. Man scarcely dares to venture in the steppes of Siberia, the plains of Central Asia, the deserts of Africa, the prairies of America, the immense wilds of Australia, or in the icy solitudes of the Poles. The most daring shrink back; the most courageous succumb. We cannot penetrate them. The means of transport are insufficient. The heat, disease, and savagery of the natives form so many impassable barriers. Twenty miles of desert separate men more than five hundred miles of ocean! One coast is neighbour to another, but if only a forest separates us, we are strangers. England is contiguous to Australia; while Egypt, for instance, seems to be millions of leagues from Senegal, and Peking at the very antipodes of St. Petersburg! The sea is more easily crossed than any Sahara, and it is thanks to it, as an American scholar4 has justly said, that a universal kinship has been established among all the parts of the world.”

Paganel spoke with such warmth that even the Major had nothing to say against this hymn to the ocean. If the finding of Harry Grant had involved following the 37th parallel across the northern continents instead of the southern oceans, the enterprise could not have been attempted; but the sea was there, ready to carry the travellers from one country to another, and on the 6th of December, at the first streak of the day, they saw a fresh mountain emerging from the bosom of the waves.

This was Amsterdam Island, situated in 37° 47′ latitude and 77° 24′5 longitude, whose high cone is visible from fifty miles away in clear weather. At eight o’clock, its form, indistinct though it still was, seemed almost a reproduction of Tenerife.

“And consequently it must resemble Tristan da Cunha,” said Glenarvan.

“A very wise conclusion,” said Paganel, “according to the geometrical axiom that ‘that two islands, similar to a third, resemble one another.’ I will only add that, like Tristan da Cunha, Amsterdam Island is also rich in seals and Robinsons.”

“So, there are Robinsons everywhere?” said Lady Helena.

“Indeed, Madame,” said Paganel, “I know of few islands which have not had their adventures of this kind, and the romance of your immortal countryman, Daniel Defoe, had been often enough realized before his day.”

“Monsieur Paganel,” said Mary, “may I ask you a question?”

“Two if you like, my Miss, and I will undertake to answer them.”

“Well,” said the girl, “would you be much afraid of being abandoned on a desert island?”

“Me?” exclaimed Paganel.

“Come, my friend,” said the Major, “don’t go and tell us that it is your dearest wish.”

“I don’t pretend that,” said Paganel. “But such an adventure would not be very unpleasant to me. I would begin a new life. I would hunt and fish. I would go home to a cave in winter and a tree in summer. I would make storehouses for my harvests; in one word, I would colonize my island.”

“All alone?”

“Alone, if necessary. Besides, are we ever alone in the world? Cannot one find friends among the animals, and tame a young kid, eloquent parrot, or amiable monkey? And if a lucky chance should send one a companion, like the faithful Friday, what more is needed to be happy? Two friends on a rock, that’s happiness. Suppose the Major and I—”

“Thank you,” interrupted the Major. “I have no taste for that sort of life, and should make a very poor Robinson Crusoe.”

“Dear Monsieur Paganel,” said Lady Helena, “you are letting your imagination run away with you. But reality is very different from the dream. You are thinking of those imaginary Robinsons, thrown onto a carefully chosen island, and treated like spoilt children by nature. You only see the beautiful side.”

“What, Madame! You don’t believe a man could be happy on a desert island?”

“I do not. Man is made for society, not for isolation. Solitude can only engender despair. It is a question of time. At the outset it is quite possible that material wants, and the very necessities of existence may engross the poor shipwrecked fellow just snatched from the waves, but afterwards, when he feels himself alone, far from his fellow-men, without any hope of seeing country and friends again, what must he think, what must he suffer? His little island is all his world. The whole human race is shut up in himself, and when death comes, which utter loneliness will make terrible, he will be like the last man on the last day of the world. Believe me, Monsieur Paganel, such a man is not to be envied.”

Paganel regretfully acknowledged the arguments of Lady Helena, but still kept up a discussion on the advantages and disadvantages of isolation, until the very moment the Duncan dropped anchor about a mile off Amsterdam Island.

This isolated group in the Indian Ocean consists of two distinct islands, thirty-three miles apart, and situated exactly on the meridian of the Indian Peninsula. To the north is Amsterdam, or Saint Pierre Island, and to the south Saint Paul, but they have been often confounded by geographers and navigators.

These islands were discovered in December, 1796, by the Dutchman, Vlaming, and observed again by d’Entrecasteaux, who led the Esperance and Recherche expedition to find La Pérouse. It is from this voyage that the confusion of the islands dates. The cartographer Beautemps-Beaupré in his atlas of the d’Entrecasteaux expedition, then Horsburg, Pinkerton, and other geographers, have constantly described Saint Pierre Island for Saint Paul Island, and vice versa. In 1859, the officers of the Austrian frigate Novara, in her circumnavigation voyage, avoided making this mistake, which Paganel particularly wanted to rectify.

Saint Paul Island lying south of Amsterdam Island, is nothing but an uninhabited islet, a conical mountain that must be the remains of an ancient volcano. On the other hand, Amsterdam Island — to which the long boat conveyed the passengers of the Duncan — is about twelve miles in circumference. It is inhabited by a few voluntary exiles, who have become used to their dreary life. They are the guardians of the fishery which belongs, as well as the islands, to a M. Otovan, a merchant from Reunion. This sovereign, though not yet recognized by the European powers, enjoys a civil list of 75,000 to 80,000 francs,6 by fishing, salting, and exporting a fish called the Cheilodactylus, also known more commonly as “cod.”

Moreover, this Amsterdam island was destined to become and remain French. In fact, it belonged first, by right of first occupation, to M. Camin of Saint-Denis, Bourbon; then it was ceded, by virtue of some international contract, to a Pole, who had it cultivated by Madagascan slaves. But when I say Polish, I also mean French, and the island became French again in the hands of Sieur Otovan.

When the Duncan visited the island on December 6th, the population consisted of three people — a Frenchman, and two mulattoes — all three employed by the merchant proprietor. Paganel was delighted to shake hands with a countryman in the person of respectable M. Viot. This “wise old man” did the honours of the island with much politeness. It was a happy day for him when he received friendly foreigners. Saint Pierre was only frequented by seal fishermen, and now and then a whaler, the crews of which are usually rough, coarse men.

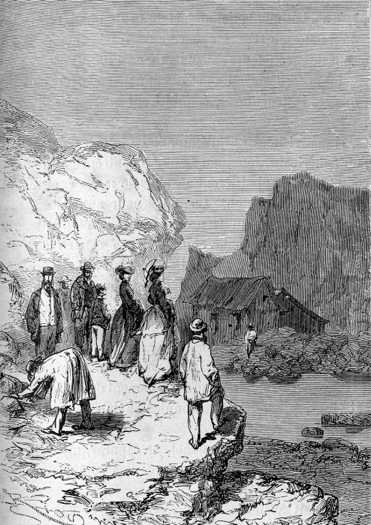

The little house where the three islanders lived was nestled in a natural harbour

M. Viot presented his subjects, the two mulattoes. They composed the whole living population of the island, except for a few wild boars in the interior, and myriads of penguins. The little house where the three islanders lived was nestled in a natural harbour on the southwest, formed by the collapse of a portion of the mountain.

It was long before the reign of Otovan Ist that Saint Pierre served as a refuge for shipwrecked men. Paganel related an interesting story about this, which he called “The History of Two Scots, cast away on Amsterdam Island.”

It was in 1827 that the English ship Palmira, passing within sight of the island, noticed smoke curling in the air, and on approaching the shore, saw two men making signals of distress. The captain sent a boat ashore, and brought them back to his vessel. The two poor fellows were hardly recognizable. One was a young man named Jacques Pain, about 22 years of age, and the other was older, 48 years old, whose name was Robert Proudfoot. For 18 months they had been almost without food or fresh water, living on shell-fish, and fishing with an old bent nail. Occasionally they had caught a young wild boar, but they often went for three days at a time without food, watching like vestals over the fire which they had lighted with their last piece of tinder, never letting it go out, and carrying it with them in their excursions, as a thing of priceless value. Such was the life of misery, privation, and suffering which they had led. Paine and Proudfoot had been landed on the island by a schooner engaged in seal fishing. According to the usual custom of seal fishermen, they were to remain on the island a month, and collect a supply of oil and skins, waiting for the return of the schooner. The schooner did not reappear. Five months afterwards, the Hope, bound for Van Diemen’s, put in at the island, but her captain, by a barbarous and inexplicable caprice, refused to take the poor Scots on board, and went away without even leaving them a biscuit or a lighter. The unfortunate men would likely have perished, but for the timely arrival of the Palmira.

The second adventure related by Paganel in the history of Amsterdam Island — if such a rock can have a history — was that of Captain Peron, a Frenchman this time. This adventure, moreover, begins like that of the two Scots and ends likewise: a voluntary release on the island, a ship which does not return, and a foreign ship that the chance of the winds brings to this group, after forty months abandonment. Only a bloody drama marked the stay of Captain Peron, and it offers many curious points of resemblance to the imaginary events which occurred in the history of Defoe’s hero.

Captain Peron had landed on the island with four sailors, two of them English and two French, intending to hunt sea lions for fifteen months. They were very successful, but when the fifteen months came to an end, and no vessel returned, and their provisions dwindled, international relations became difficult. The two English sailors revolted against their captain, and would have killed him but for the interference of his fellow countrymen. From that moment the two parties watched each other night and day, always armed for attack, and alternately conquerors and conquered. They led a frightful existence of misery and anguish. In the end one faction would have undoubtedly slain the other, if some English ship hadn’t repatriated these unfortunate men that a miserable question of nationality divided on a rock of the Indian Ocean.

Twice then, had Amsterdam Island become the home of abandoned sailors, providentially saved from misery and death. But since these events no vessel had been lost on its coast. Had any shipwreck occurred, some fragments must have been thrown on the sandy shore, and any poor sufferers from it would have found their way to M. Viot’s fishery. The old man had been on the island for many years, and had never been called upon to exercise such hospitality. Of the Britannia and Captain Grant he knew nothing. Neither Amsterdam Island nor St. Paul Island, which whalers and fishermen often visited, had been the scene of this catastrophe.

Glenarvan was neither surprised nor saddened by his answer. His object in asking was to establish the fact that Captain Grant had not been there, rather than that he had. This done, they were ready to proceed on their voyage next day.

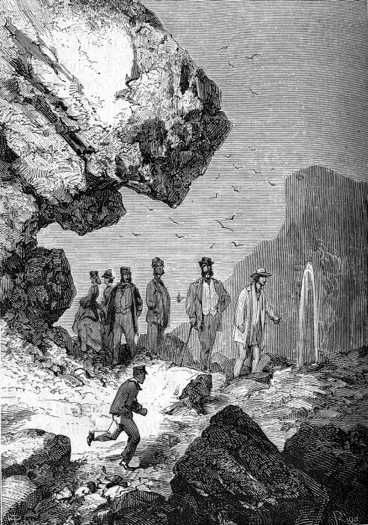

Here and there thermal springs escaped from the black lava

They rambled about the island until evening, as its appearance was very inviting. Its fauna and flora would not have filled the octavo of the most prolific naturalists. The order of quadrupeds, birds, fish, and cetaceans, contained only wild boars, snow petrels, albatrosses, perch, and seals. Here and there thermal springs and chalybeate waters escaped from the black lava, and thick vapours rose above the volcanic soil. Some of these springs were very hot. John Mangles held his thermometer in one of them, and found the temperature was 176 degrees Fahrenheit7. Fish caught in the sea a few yards off, cooked in five minutes in these almost boiling waters, which persuaded Paganel not to attempt to bathe in them.

Toward evening, after a good walk, Glenarvan bid farewell to the honourable M. Viot. Everyone wished him all the happiness possible on his desert island. In return, the old man gave his blessings to the expedition, and the Duncan’s boat brought her passengers back on board.

1. These winds run counter to the trade winds below the 30th parallel.

2. 700 leagues (2,800 kilometres — DAS)

Verne had 1,300 miles and 600 leagues — DAS

3. 1,350 leagues. (5,400 kilometres — DAS)

4. Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury. (“The Father of Modern Oceanography.” A particular favourite of Verne’s. He gets several mentions in 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas, as well. — DAS)

5. 75° 4′ east of the Paris meridian.

6. $15,000 to $16,000 , £3,000 to £3,200. — DAS

7. 80 degrees centigrade.