Boats were sent ashore to examine the coast minutely

John Mangles’ first care was to moor his vessel securely on two anchors. He anchored in five fathoms of water, with a hard gravel bottom which gave an excellent hold. There was no danger now of either being driven away or stranded at low water. After so many hours of danger, the Duncan found herself in a cove, sheltered by a high circular point from the offshore winds.

Lord Glenarvan shook hands with John Mangles, simply saying “Thanks, John.”

John felt generously rewarded by those two words. Glenarvan kept his secret anguish to himself, and neither Lady Helena, nor Mary or Robert suspected the grave peril they had just escaped.

One important fact had to be ascertained. Where on the coast had the Duncan be thrown by the storm? How far must they go to regain the parallel? How far to the southwest was Cape Bernouilli? These were the first questions addressed to John Mangles. He immediately took his bearings, and pointed out his observations on the map.

The Duncan had not deviated too far from her course: only two degrees. They were at 136° 12′ of longitude, and 35° 07′ latitude, at Cape Catastrophe in South Australia, three hundred miles from Cape Bernouilli.

Cape Catastrophe, an ominous sounding name, lies across Investigator Strait from Cape Borda, formed by a promontory on Kangaroo Island. Investigator Strait leads to two deep gulfs — Spencer Gulf in the north, and Gulf St. Vincent in the south. The port of Adelaide, the capital of the province of South Australia, lies on the eastern coast of Gulf St. Vincent. This city, founded in 1836, numbers forty thousand inhabitants, and many resources would be available there. But its people are too much taken up with the cultivation of their fertile soil, and with looking after their grapes and oranges, and all their agricultural wealth, to occupy themselves with great industrial enterprises. The population comprises fewer engineers than agriculturists, and the general spirit runs neither in the direction of commercial operations nor mechanical arts.

Could the Duncan be repaired there? To answer that question, the extent of the damages first had to be determined. Captain Mangles ordered some men to dive down below the stern to inspect the screw. Their report was that one of the blades of the screw was bent, and was jammed against the sternpost,1 which prevented all possibility of rotation. This was serious damage, that could not likely be repaired with the resources available in Adelaide.

Lord Glenarvan and Captain John, after careful consideration, decided to sail along the Australian coast, looking for signs of the Britannia. They would stop at Cape Bernouilli to collect the latest information available there, and then continue south to Melbourne, where the Duncan could easily be repaired. With the screw restored, they would proceed to cruise along the eastern coast to complete their search.

This proposal was approved. John Mangles resolved to take advantage of the first fair wind to sail. He did not have to wait long. By evening the hurricane had completely subsided. A manageable breeze followed it, blowing from the southwest. Repairs were made to the rigging, and new sails were taken from stores. At four o’clock in the morning, sailors turned the capstan. Soon the anchors were raised and the Duncan, under her foresail, topsail, topgallant, jibs, brigantine, and her staysails, ran on the starboard tack close hauled to the wind along the Australian shores.

Two hours later she lost sight of Cape Catastrophe, and found herself across Investigator Strait. In the evening they doubled Cape Borda, and came alongside Kangaroo Island. This is the largest of the Australian islands, and serves as a refuge for fugitive deportees. Its appearance was enchanting. The stratified rocks on the shore were carpeted with lush vegetation. As in the time of its discovery in 1802, countless mobs of kangaroos leaped through the woods and plains.

Boats were sent ashore to examine the coast minutely

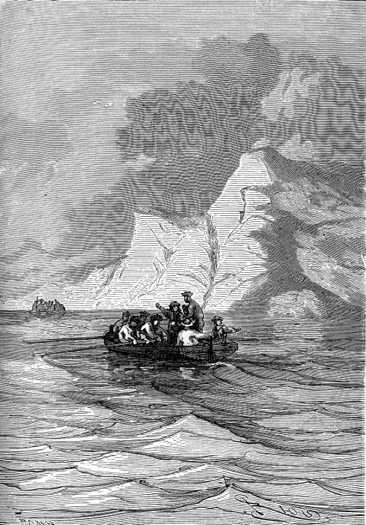

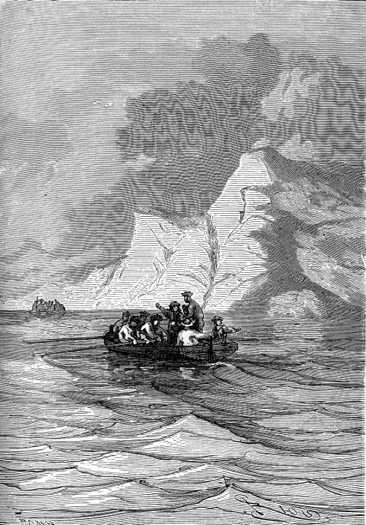

Next day, while the Duncan was sailing offshore, boats were sent in to examine the coast minutely, as they were now on the 36th parallel, and between that and the 38th, Glenarvan wished to leave no part unexplored.

On December 18th the Duncan, which flew along before the wind like a regular clipper, sailed close past Encounter Bay. It was here that the explorer Sturt came in 1828, after he had discovered the Murray: the largest river in southern Australia. They were no longer sailing past the green shores of Kangaroo Island, but a low and jagged coast of arid hills showing all the dryness of a polar continent. Sometimes the uniformity was broken by some grey cliffs, or sand promontories.

The boats did hard service during this journey, but the sailors never complained. Almost always Glenarvan and his inseparable companions, Paganel and young Robert, accompanied them. They wanted to search for some vestiges of the Britannia with their own eyes. But all this painstaking exploration revealed nothing of the shipwreck. The Australian shores revealed no more than the Patagonian. However, it was not yet time to lose all hope. They had not reached the exact point indicated by the document. This extended search was a precaution, to leave nothing to chance. During the night, the Duncan hove to, so as to remain in place as much as possible, and during the day the coast was carefully searched.

On December 20th, they arrived off Cape Bernouilli, which terminates Lacepede Bay, without finding any trace of the Britannia. Still this was not surprising, for in the two years since the catastrophe the sea might, and indeed must, have scattered and destroyed whatever fragments of the three-master had remained. Besides, the natives, who scent a wreck as the vultures do a dead body, would have collected the smallest debris. Then, Harry Grant and two his companions, taken prisoner the moment the waves threw them on shore, had undoubtedly been dragged into the interior of the continent.

But if so, what became of Paganel’s ingenious hypothesis about the document? In the Argentine territory, the geographer could rightly contend that the figures in the document related not to the theatre of the sinking, but to their place of captivity. Indeed the great rivers of the Pampas, with their numerous tributaries were there to bring the precious document to the sea. Here, in this part of Australia, the rivers which cross the 37th parallel are scarce. Besides, the Patagonian rivers — the Rio Colorado and the Rio Negro — throw themselves into the sea along deserted beaches, uninhabitable and uninhabited, while the main Australian rivers — the Murray, Yarra, Torrens, and Darling — are tributaries to each other, or rush into the ocean by mouths which have become frequented ports. Ports where navigation is active. What was the chance, then, that a fragile bottle could have descended the course of these incessantly traversed waters and arrived at the Indian Ocean?

This impossibility could not escape insightful minds. Paganel’s hypothesis, plausible in Argentina, would have been illogical in Australia. Paganel recognized this problem when it was raised by Major MacNabbs. It was evident that the position reported in the document related to the place where the Britannia was actually shipwrecked, and not to the place of captivity, and that the bottle therefore had been thrown into the sea on the western coast of the continent.

As Glenarvan correctly pointed out, this interpretation did not exclude the hypothesis that Captain Grant was a captive. The document anticipated that they were to be taken prisoners of the cruel natives, but there was no longer any reason to look for the prisoners on the 37th parallel, rather than any other.

After a long debate, the question was resolved with a final conclusion: if traces of the Britannia were not found at Cape Bernouilli, Lord Glenarvan would have to return to Europe. His search would have been fruitless, but he had done his duty courageously and conscientiously.

This saddened the passengers of the yacht, especially Mary and Robert Grant. On their way to the shore with Lord and Lady Glenarvan, John Mangles, MacNabbs, and Paganel, the captain’s two children said that the question of their father’s salvation was about to be irrevocably decided. Irrevocable, indeed, they might consider it, for as Paganel had judiciously demonstrated, if the wreck had occurred on the eastern side, the survivors would have long since found their way back to their own country.

“Hope! Hope! Always hope!” Lady Helena repeated to the girl, sitting next to her in the boat that was taking them to shore. “The hand of God will not leave us!”

“Yes, Miss Mary,” said Captain John. “It is at the moment when men have exhausted human resources, that Heaven intervenes, and, by some unforeseen fact, opens new ways to them.”

“God hear you, Mr. John!” said Mary Grant.

The shore was only a cable away. The cape which extended two miles into the sea ended in gentle slopes. The boat put in at a sort of natural cove between coral banks still in the process of formation. In time they might form a reef belt around the southern part of Australia. Even now they were quite enough to destroy the keel of any ship that grounded on them, and the Britannia might have been dashed to pieces on them.

The Duncan’s passengers landed without difficulty on an absolutely deserted shore. The coast was formed by cliffs of stratified rock, sixty to eighty feet high. It would have been difficult to scale without ladders or crampons. Fortunately, John Mangles discovered a breach half a mile to the south. Part of the cliff had collapsed. The sea, no doubt, had beat this barrier of friable tuff during its great equinoctial rages, and caused the fall of the upper portions of the plateau.

Glenarvan and his companions entered the gully, and reached the summit of the cliff via a steep slope. Robert climbed like a young cat, and was first to the top ridge, to the despair of Paganel who was quite ashamed to see his long legs, forty years old, outdistanced by the young legs of a twelve year old. However, he was far ahead of the peaceful Major, who did not care otherwise.

The little troop, soon reunited, examined the plain that stretched before their eyes. It appeared entirely uncultivated, and covered with shrubs and bushes. It was an arid land, which Glenarvan thought resembled some of the glens of the Scottish Lowlands, and to Paganel like some barren heaths of Brittany. But if this country appeared uninhabited along the coast, the presence of man, not the savage, but the worker, was revealed in the distance by some auspicious constructions.

“A mill!” exclaimed Robert.

Three miles away, the wings of a windmill were turning in the wind.

“It certainly is a windmill,” said Paganel after examining the object in question through his telescope. “Here is a small monument as modest as it is useful. It is a privilege to lay my eyes on such an enchanting sight.”

“It’s almost a steeple,” said Lady Helena.

“Yes, Madame, and if one grinds the bread of the body, the other grinds the bread of the soul. From this point of view they are very alike.”

“Let us go to the mill,” said Glenarvan.

A plain and comfortable dwelling, crowned by a merry mill

They started on their way, and after walking about half an hour, the country began to change, showing it had been worked by the hand of man. The transition from the barren countryside to cultivation was abrupt. Instead of scrub, hedgerows surrounded a recently cleared enclosure. A few oxen and half a dozen horses grazed in meadows surrounded by sturdy acacias transplanted from the vast nurseries of Kangaroo Island. Gradually fields of grain came in sight, a few acres bristling with blond ears of corn, haystacks shaped like large beehives, blooming orchards, a fine garden worthy of Horace, where the pleasant mingled with the useful. Then came sheds, well distributed out buildings, and, last of all, a plain comfortable house, which the merry mill dominated with its sharp gable and caressed with the moving shadows of its large sails.

A pleasant-faced man, about fifty years old, came out of the house, warned of the arrival of strangers by the loud barking of four dogs. He was followed by five handsome and strong boys, his sons, and their mother, a tall, robust woman. There was no mistaking the little group. This man, surrounded by his valiant family, in the midst of these new constructions, in this almost virgin countryside, was a perfect example of the Irish colonist: a man who, weary of the miseries of his country, had come, with his family, to seek fortune and happiness beyond the seas.

Before Glenarvan and his party had time to reach the house, and present themselves in due form, they heard the cordial words “Strangers! Welcome to the house of Paddy O’Moore!”

Glenarvan took the man’s outstretched hand. “Are you Irish?”

“I was,” said Paddy O’Moore, “but now I am Australian. Come in, gentlemen, whoever you may be, this house is yours.”

It was impossible not to accept an invitation given with such grace. Lady Helena and Mary Grant were led in by Mrs. O’Moore, while the gentlemen were assisted by his sturdy sons to disencumber themselves of their fire-arms.

An immense hall, light and airy, occupied the ground floor of the house, which was built of strong planks laid horizontally. The hall was furnished with a few wooden benches fastened against the cheerfully coloured walls, a dozen stools, two oak chests on which there was a display of white porcelain and shiny pewter, and a large long table where twenty guests could sit comfortably. It was all in perfect keeping with the solid house and sturdy inhabitants.

Lunch was served. The soup tureen was steaming between roast beef and a leg of mutton, surrounded by large plates of olives, grapes, and oranges. The necessary was there, and there was no lack of the superfluous. The host and hostess were so pleasant, and the big table, with its abundant fare, looked so inviting, that it would have been ungracious not to have seated themselves. The farm-hands, on equal footing with their employer, were already in their places to take their share of the meal.

Paddy O’Moore pointed to the seats reserved for the strangers, and said “I was waiting for you.”

“Waiting for us?” asked Glenarvan.

“I am always waiting for those who come,” said the Irishman. And then, in a solemn voice, while the family and hands reverently stood, he recited the blessing. Lady Helena felt very moved by such a perfect simplicity of manners, and a glance from her husband made her understand that he admired it as she did.

Dinner followed immediately, during which an animated conversation was kept up on all sides. From Scottish to Irish is but a hands breadth. The Tweed,2 several fathoms wide, digs a deeper trench between Scotland and England than the twenty leagues of Irish Channel which separates Old Caledonia from Érin.

Paddy O’Moore related his history. It was that of all immigrants driven by misfortune from their own country. Many come to seek fortunes who only find trouble and sorrow, and then they throw the blame on bad luck, and forget that the true cause is their own idleness, and vice, and want of common sense. Whoever is sober and courageous, honest and economical, succeeds.

Such a one had been, and was, Paddy O’Moore. He left Dundalk, where he was starving, and came with his family to Australia. He landed at Adelaide, where he chose the hard work of a farmer, over the more hazardous work of a miner. Two months later he started clearing his own land, and so prospers today.

The whole territory of South Australia is divided into eighty acre lots3, and these are sold to colonists by the government. An industrious man, by proper cultivation, can not only make a living out of his lot, but lay aside eighty pounds4 a year.

Paddy O’Moore knew this. His knowledge of farming served him well. He lived, he saved, and acquired new lots with the profits from the first. His family prospered, and also his farm. The Irish peasant became a landowner, and though his little estate was not yet two years old, he had five hundred acres cleared by his own hands, and five hundred head of cattle. He was his own master, after having been a serf in Europe, and as independent as one can be in the freest country in the world.

His guests congratulated this Irish immigrant heartily as he ended his narration. Paddy O’Moore, his story over, waited, no doubt expecting the strangers to recite their own story in turn, but he didn’t demand it from them. He was one of those discreet people who can say, “I tell you who I am, but I don’t ask who you are.” Glenarvan wanted to tell him of the Duncan, and how they came to Cape Bernouilli, and of the search they pursued with tireless perseverance. But first he questioned Paddy O’Moore about the sinking of the Britannia.

The reply of the Irishman was not favourable. He had not heard of this ship. For the past two years, no ship had been wrecked on that coast, neither above nor below the Cape. The catastrophe was only two years ago. He could declare with the greatest certainty that the survivors of the wreck had not been thrown on this part of the western shore.

“Now, My Lord,” he added “may I ask what interest you have in making the inquiry?”

Glenarvan told the settler the story of the document, the voyage of the Duncan, the attempts to find Captain Grant. He did not conceal that his dearest hopes fell before so clear a claim, and that he despaired of every finding the shipwrecked Britannia.

Glenarvan’s final words made a painful impression on the minds of his listeners. Robert and Mary’s eyes filled with tears as they listened to him. Paganel couldn’t find a word of hope, or comfort to give them. John Mangles was suffering from a pain he could not soften. Despair was invading the souls of the generous people whom the Duncan had brought unnecessarily to these distant shores, when these words were heard:

“My Lord, praise and thank God! If Captain Grant is alive, he is on Australian soil!”

1. The upright structural member or post at the stern of a ship.

2. The river that separates Scotland from England.

3. One acre is 0.405 hectare.

4. £80 = $400 = 2,000 francs.