He was a coarse-looking fellow, about forty-five years old

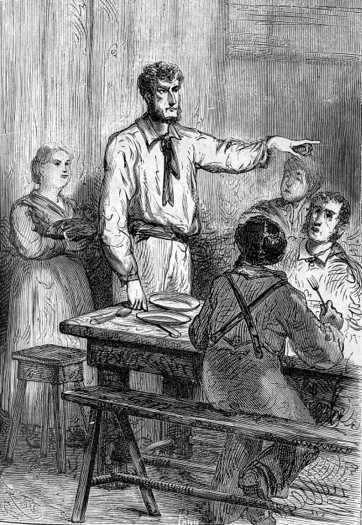

The surprise caused by these words cannot be described. Glenarvan sprang to his feet, pushing back his seat “Who said that?”

“I did,” said one of the farm hands, at the far end of the table.

“You, Ayrton?” said the settler, no less bewildered than Glenarvan.

“Yes, it was me,” said Ayrton in a firm, though somewhat agitated voice. “A Scot like yourself, My Lord, and one of the shipwrecked crew of the Britannia.”

This declaration produced an indescribable effect. Mary Grant fell back in Lady Helena’s arms, half-fainting from joy. Robert, Mangles, and Paganel jumped up and rushed toward the man that Paddy O’Moore had addressed as Ayrton.

He was a coarse-looking fellow, about forty-five years old

He was a coarse-looking fellow, about forty-five years old, with very bright eyes, though half-hidden beneath thick, overhanging brows. In spite of his extreme leanness there was an air of unusual strength about him. He seemed all bone and nerves, or, to use a Scottish expression, he had not wasted time in making fat. He was broad shouldered, of middle height, and determined bearing. His face was so full of intelligence and energy, that though his features were rough, he gave a favourable impression. The sympathy he inspired was further increased by the marks of recent suffering imprinted on his face. It was evident that he had endured long and severe hardships, which he had borne bravely, and overcome.

Glenarvan and his friends were drawn to him at first sight. Ayrton’s personality was obvious from the start. This meeting had evidently surprised both of them. Glenarvan took over, asking all the questions his friends wanted to ask, and to which Ayrton replied.

His first questions rushed out of him before he could think to put them in logical order.

“Are you one of the castaways of the Britannia?”

“Yes, My Lord. Captain Grant’s quartermaster.”

“Saved with him after the sinking?”

“No, My Lord, no. I was separated from him at that terrible moment, for I was swept off the deck as the ship struck.”

“Then you are not one of the two sailors mentioned in the document?”

“No. I didn’t know about any document. The captain must have thrown it into the sea when I was no longer on board.”

“But the captain? The captain?”

“I thought I was the only survivor”

“I thought he had drowned; gone down with all the crew of the Britannia. I thought I was the only survivor.”

“But you said just now, Captain Grant was alive.”

“No,” I said, ‘If the captain is alive…’”

“And you added ‘he is on the Australian continent.’”

“Where else could he be?”

“Then you don’t know where he is?”

“No, My Lord. I say again, I supposed he was buried beneath the waves, or broken on the rocks. It was from you I learnt that he was still alive.”

“Then, what do you know?” asked Glenarvan.

“Simply this: if Captain Grant is alive, he is in Australia.”

“Where did the shipwreck occur?” asked Major MacNabbs.

This should have been the first question, but in the confusion caused by the unexpected incident, and in his rush to learn of Captain Grant’s fate, Glenarvan had forgotten to ask it. After the Major’s question, the previously vague, illogical conversation, proceeding by leaps and bounds, touching on subjects without deepening them, mingling the facts, swapping the dates, took on a more reasonable pace. Soon the details of this obscure story appeared, clear and precise in the minds of its listeners.

To the question put by the Major, Ayrton replied “When I was swept off the forecastle where I was hauling down the jib, the Britannia was running toward the Australian coast. She was not more than two miles from it. The sinking happened there.”

“By 37° of latitude?” asked John Mangles.

“Yes, by 37°.”

“On the west coast?”

“No! On the east coast,” replied the quartermaster quickly.

“And at what date?”

“It was on the night of June 27th, 1862.”

“That’s it! That’s it!” exclaimed Glenarvan.

“You see then, My Lord,” said Ayrton, “why I say that if Captain Grant is alive, it is on the Australian continent that he must be sought, and not anywhere else.”

“And we will look for him there, and we will find him, and we will save him, my friend!” exclaimed Paganel. “Ah, precious document,” he added, with perfect naiveté, “you must admit you have fallen into the hands of uncommonly shrewd people.”

But, doubtless, nobody heard his flattering words. Glenarvan and Lady Helena, Mary and Robert huddled around Ayrton. They shook his hands. It seemed as if this man’s presence was a sure guarantee of Harry Grant’s salvation. If this sailor had escaped the dangers of the shipwreck, why shouldn’t the captain? Ayrton was happy to say that Captain Grant must be alive as well. Where, he could not say, but certainly on this continent. He answered the thousand questions that assailed him with remarkably intelligence and precision. Miss Mary held one of his hands in hers, all the time he spoke. This sailor was a companion of her father’s, one of the Britannia’s seamen! He had lived with Harry Grant, crossed the seas with him, and shared the same dangers. Mary could not take her eyes off his rough face, and she wept with happiness.

So far, no one had thought of questioning the veracity or the identity of the quartermaster. Only the Major, and perhaps John Mangles, less quick to jump to conclusions, began to ask themselves if Ayrton’s word was to be fully trusted. There was something suspicious about this unexpected meeting. Certainly Ayrton had mentioned corresponding facts and dates, and the minuteness of his details was most striking. But details, as exact as they were, do not form certainty, and generally, it has been noted, a lie is affirmed by the precision of its details. MacNabbs reserved his opinion.

John Mangles’ doubts didn’t resist the words of the sailor for long. He was convinced that Ayrton had been a true companion of Captain Grant’s when he heard him speak to the young girl about her father. Ayrton knew Mary and Robert quite well. He had seen them in Glasgow when the Britannia had sailed. He remembered them at the farewell dinner given on board the Britannia for the captain’s friends, at which Sheriff MacIntyre was present. Robert, who was barely ten years old, had been entrusted to Dick Turner, the boatswain, and he had escaped him, and climbed up to the topgallant’s yards.

“That’s right; I did!” said Robert.

And Ayrton recalled a thousand little facts, without appearing to attach the importance that John Mangles gave to them, and when he stopped, Mary Grant said, in her soft voice “Oh, go on, Mr. Ayrton, tell us more about our father!”

The quartermaster did his best to satisfy the girl’s desires, and Glenarvan did not interrupt him, though a score of questions far more important crowded into his mind. Lady Helena made him look at Mary’s beaming face, and the words he was about to utter remained unspoken.

It was in this conversation that Ayrton told the story of the Britannia and her voyage through the Pacific. Mary Grant knew most of it, as news of the ship had come regularly up to May of 1862. During this year, Harry Grant had landed at all the principal lands of Oceania. He touched the Hebrides, New Guinea, New Zealand, and New Caledonia, often encountering unjustified seizures, subject to the ill will of the English authorities, as his mission was reported in the British colonies. He had succeeded in finding a likely place on the western coast of Papua, where it seemed that a prosperous Scottish colony could be established. A good port of call on the Maluku and Philippine route would attract ships, especially when the completion of the Suez Canal supplanted the Cape of Good Hope route. Harry Grant was one of those who appreciated the great work of M. de Lesseps, and would not allow political rivalries to interfere with international interests.

He found himself in the hands of natives

After surveying Papua, the Britannia went to refuel at Callao, and left that port on the 30th of May, 1862, to return to Europe via the Indian Ocean and the Cape. Three weeks later, a terrible storm disabled the ship. It had been necessary to cut away the masts. A leak sprang in the hold, and could not be stopped. The crew were soon too exhausted to work the pumps, and for eight days the Britannia was tossed about like a toy in the hurricane. She had six feet of water in her hold, and was gradually sinking. The boats had all been carried away by the tempest; death stared them in the face, when, on the night of the 27th of June, as Paganel had rightly supposed, they came in sight of the eastern coast of Australia. The ship soon neared the shore, and presently dashed violently against it. Ayrton was swept off by a wave, and thrown among the breakers, where he lost consciousness. When he recovered, he found himself in the hands of natives, who dragged him away into the interior of the continent. Since that time he had never heard the Britannia’s name mentioned, and reasonably enough came to the conclusion that she had gone down with all hands on the dangerous reefs of Twofold Bay.

Here ended the story of Captain Grant. More than once sorrowful exclamations were evoked by the story. The Major could not, in common justice, doubt its authenticity. But after the story of the Britannia, Ayrton’s particular story was of even more interest. Thanks to the document, they knew that Grant had survived the sinking with two of his sailors, like Ayrton himself. They should be able to deduce Captain Grant’s fate from Ayrton’s. He was invited to tell the story of his adventures. It was very simple and very short.

The seaman, a prisoner of a native tribe, was taken inland, to those areas watered by the Darling River, four hundred miles north of the 37th parallel. He spent a miserable existence there — not that he was ill-treated, but the natives themselves lived miserably. He passed two long years of painful slavery among them, but always cherished in his heart the hope of one day regaining his freedom, and watching for the slightest opportunity that might turn up, though he knew that his flight would be attended with innumerable dangers.

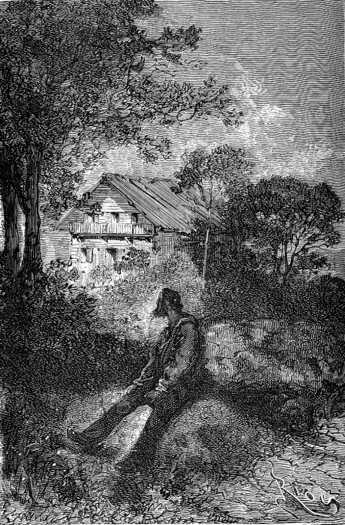

He reached the house of Paddy O’Moore

One night in October, 1864, he managed to escape the vigilance of the natives, and disappeared into the depths of the immense forests. For a month he subsisted on roots, edible ferns, and mimosa gums, wandering through vast solitudes, guiding himself by the sun during the day and by the stars at night, often depressed by despair. He went on across marshes, rivers, and mountains, until he had traversed the whole of the uninhabited continent, where only a few bold travellers have ventured. At last, in an exhausted and all but dying condition, he reached the hospitable house of Paddy O’Moore, where he found a happy home in exchange for his labour.

“And if Ayrton speaks well of me,” said the Irish settler when the narrative ended, “I have nothing but good to say of him. He is an honest, intelligent fellow, and a good worker; and as long as he pleases, Paddy O’Moore’s house shall be his.”

Ayrton thanked the Irishman with a gesture, and waited for new questions to be put to him. He told himself, however, that he surely must have satisfied all legitimate curiosity. What could remain to be said that he had not said a hundred times already? Glenarvan was about to open a discussion about their future plan of action, based on this encounter with Ayrton, and the information he had given them, but Major MacNabbs had one more question.

“You were the quartermaster, aboard the Britannia?”

“Yes,” said Ayrton, without the least hesitation. But as if conscious that a certain feeling of mistrust, however slight, had prompted this question from the Major, he added “I have my contract with me; I saved it from the wreck.”

He left the common room immediately to fetch this official document, and, though hardly absent a moment, Paddy O’Moore had time to say “My Lord, you may trust Ayrton; I vouch for him being an honest man. He has been in my service for two months now, and I have never once found fault with him. I knew all this story of the shipwreck and his captivity. He is a loyal man, worthy of all your confidence.”

Glenarvan was about to reply that he had never doubted his good faith, when Ayrton came back with his contract papers. It was signed by the shipowners and Captain Grant. Mary recognized her father’s writing at once. It certified that “Tom Ayrton, able seaman, was engaged as quartermaster on board the three-master Britannia, Glasgow.” There was no longer any doubt as to Ayrton’s identity, for it would have been difficult to account for his possession of the document if he were not the man named in it.

“Now,” said Glenarvan, “I wish to ask everyone’s advice as to how we should proceed. Your advice, Ayrton, will be particularly valuable to us, and I shall be much obliged if you would let us have it.”

“I thank you, My Lord, for the confidence you show toward me, and I hope to prove worthy of it,” said Ayrton. After a moment’s thought he went on “I have some knowledge of the country, and the habits of the natives, and if I can be of service to you…”

“Certainly,” said Glenarvan.

“I think,” said Ayrton, “that Captain Grant and his two sailors have been saved from wreck, but since they have not found their way to an English settlement, nor been seen anywhere, I have no doubt that their fate has been similar to my own, and that they are prisoners in the hands of some of the native tribes.”

“You repeat here, Ayrton, the arguments I have already made,” said Paganel. “The castaways are obviously prisoners of the natives, as they feared. But should we think that, like you, they were dragged away north of the 37th parallel?”

“I should suppose so, sir; for hostile tribes would hardly remain anywhere near the districts under British rule.”

“That will complicate our search,” said Glenarvan, somewhat disconcerted. “How can we possibly find traces of the captives in the heart of so vast a continent?”

No one replied, though Lady Helena’s questioning glances at her companions seemed to press for an answer. Even Paganel remained silent. His ingenuity, for once, unable to come up with an answer. John Mangles paced the common room with great strides, as if he were on the deck of his ship, evidently quite nonplussed.

“And you, Mr. Ayrton,” said Lady Helena at last. “What would you do?”

“Madam,” replied Ayrton at once, “I would embark on board the Duncan, and go straight to the scene of the shipwreck. There I would be guided by circumstances, and by any clues that chance might provide.”

“Very good,” said Glenarvan. “But we must wait until the Duncan is repaired.”

“Ah! You have suffered damage?” said Ayrton.

“Yes,” said John Mangles.

“Serious?”

“No, but repairs require tools we do not have on board. One of the blades of the screw is twisted, and we cannot get it repaired nearer than Melbourne.”

“Can’t you simply sail there?” asked the quartermaster.

“Yes, but if the Duncan encounters contrary winds, it could take a long time to reach Twofold Bay, and in any case she will have to pass by Melbourne.”

“Well, let the ship go to Melbourne then,” said Paganel, “and we will go without her to Twofold Bay.”

“How?” asked Mangles.

“By crossing Australia as we crossed America, keeping along the 37th parallel.”

“But the Duncan?” asked Ayrton, as if particularly anxious on that score.

“The Duncan can rejoin us, or we can rejoin her, as the case may be. Should we discover Captain Grant in the course of our journey, we can all return together to Melbourne. If we have to go on to the coast, then the Duncan can come to us there. Who has any objection to make? Have you, Major?”

“No,” said MacNabbs. “Not if there is a practicable route across Australia.”

“So practicable,” said Paganel, “that I propose Lady Helena and Miss Grant should accompany us.”

“Are you serious?” asked Glenarvan.

“Very serious, my dear Lord. It is a journey of 350 miles,1 no more. At twelve miles a day, it will last a mere month, enough time to complete repairs to the Duncan. If we had to cross the continent farther north, at its widest part, and traverse the immense deserts where there is no water, and torrid heat, and go where the most adventurous travellers have never yet ventured, that would be a different matter. But the 37th parallel cuts through the province of Victoria, quite an English country, with roads and railways, and well populated almost everywhere. It is a journey you might almost make in a carriage, though a wagon would be better. It is no more difficult than a trip from London to Edinburgh.”

“What about ferocious animals?” asked Glenarvan, wanting to know all of the potential hazards.

“There are no ferocious animals in Australia.”

“And how about the savages?”

“There are no savages in this latitude, and if there were, they do not have the cruelty of the New Zealanders.”

“And the convicts?”

“There are no convicts in the southern provinces of Australia, only in the eastern and western colonies. The province of Victoria not only refused to admit them, but passed a law to prevent any convicts released from other provinces entering her territories. This year the Victorian Government even threatened to withdraw its subsidy from the Peninsular Company if their vessels continued to take in coal in those ports of Western Australia where convicts are admitted. How don’t you, an Englishman, know that?”

“First of all, I am not an Englishman,” said Glenarvan.

“What Mr. Paganel says is perfectly correct,” said Paddy O’Moore. “Not only Victoria, but also South Australia, Queensland, and even Tasmania, have agreed to expel deportees from their territories. Ever since I have been on this farm, I have not heard of a single convict.”

“And for my part, I have never met any,” said Ayrton.

“You see, my friends,” continued Jacques Paganel, “very few savages, no ferocious animals, and no convicts. There are not many countries in Europe for which you can say as much. Well, is it agreed?”

“What do you think, Helena?” asked Glenarvan.

“What we all think, my dear Edward.” Lady Helena looked around at her companions. “Let us be off at once!”

1. 140 leagues (560 kilometres — DAS)

The Hetzel version has “1,200 leagues around” here, which makes no sense whatsoever.