Paganel, as usual, made himself the guide of the party

In 1814, Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, now President of the Royal Geographical Society of London, while studying their structures found many remarkable similarities between the Ural Mountains, and the chain which runs from north to south near the southern coast of Australia.

Now the Urals being a gold bearing range, it struck the learned geologist that the precious metal might very likely be found in the Australian cordillera as well. He was not wrong.

Two years later, samples of gold were sent to him from New South Wales, and he sent a large number or miners form Cornwall to the auriferous regions of New Holland.

The first nuggets were discovered in South Australia by Mr. Francis Dutton, and in New South Wales by Messrs. Forbes and Smyth.

From this first impetus, miners flocked to Australia from all parts of the globe — English, American, Italian, French, German, Chinese — but it was not till April 3rd, 1851, that Mr. Hargrave discovered very rich gold deposits, and offered to reveal their location to the Governor of Sydney, Sir Charles FitzRoy, for the modest sum of five hundred pounds.

His offer was not accepted, but the rumour of the discovery had spread, and gold-seekers directed their steps to Summerhill and Leni’s Pond. The town of Ophir was founded, and the richness of the mines soon made it worthy of its biblical name.

Up to this time there had been no mention of gold discoveries in Victoria, but it was about to take first prize for the richness of its deposits.

It was a few months later, in August, 1851, that the first nuggets of gold were dug up in that province, and soon there were large mining operations going on in four different districts: Ballarat, the Ovens, Bendigo, and Mount Alexander. They all had rich deposits, but at the Ovens the abundance of water made mining difficult; at Ballarat, the gold was so unequally distributed that labour was often fruitless, and at Bendigo the soil was very unfavourable for digging mines. It was only at Mount Alexander that every condition for success was found, and the precious ore mined there was worth as much as 1,441 francs a pound.1 The highest rate in all the markets of the world.

It was to precisely this place, so fertile in fatal ruins and in unexpected fortunes, that the 37th parallel led the searchers for Captain Harry Grant.

On December 31st, after traversing over very rough ground which tired both horses and oxen for the whole day, they saw the rounded peaks of Mount Alexander. They encamped for the night in a narrow gorge of this little chain, and the hobbled animals were set loose to graze among the quartz blocks that strewed the ground. They had not yet entered the gold fields. It was not until next day, the first day of the new year, 1866, that the wagon dug ruts in the roads of this opulent country.

James Paganel and his companions were delighted to see this famous mount, called Geboor in the Australian language. It was here that a horde of adventurers, thieves and honest men — those who hang, and who are hanged — had flocked in droves. At the first rumours of the great discovery, in the golden year of 1851, towns, fields, and ships were abandoned by settlers, squatters, and sailors. The gold fever became an epidemic, as contagious as the plague. How many died of it who thought fortune was already in their grasp? Prodigal nature, it was said, had sown millions in treasure over more than twenty-five degrees of latitude in this wonderful Australia. It was harvest time, and the reapers rushed to the ingathering.

The job of the “digger” took precedence over all the others, and, if it is true that many succumbed to the task, broken by fatigue, others enriched themselves with a single stroke of the pick. The failures were ignored; the successes shouted abroad. Those strokes of fortune were echoed to the five parts of the globe. Soon waves of the ambitious of all castes washed up on the shores of Australia. During the last four months of 1852, in Melbourne alone, there was an influx of 54,000 immigrants: an army, but an army without a leader, or discipline. An army on the day after a battle which has not yet been won; in short, 54,000 pillagers of the worst kind.

During those first years of mad intoxication it was an indescribable mess. However, the English, with their accustomed energy, soon made themselves masters of the situation. The policemen and the local constabulary took the part of the honest people over the party of robbers, and turned matters around. Glenarvan found nothing like the violent scenes of 1852. Thirteen years had elapsed since that time, and now gold mining operations were carried out in the most methodical manner, under strict management.

Besides, the placers2 were already running out. Some had been completely mined out. And little wonder that these treasures of nature had been drained, when the soil of Victoria alone had yielded £63,107,4783 sterling in gold between 1852 and 1858! The immigrants had decreased in proportion, and had gone off to countries which were still virgin. The newly discovered gold fields in Otago and Marlborough in New Zealand attracted thousands of two footed termites.4

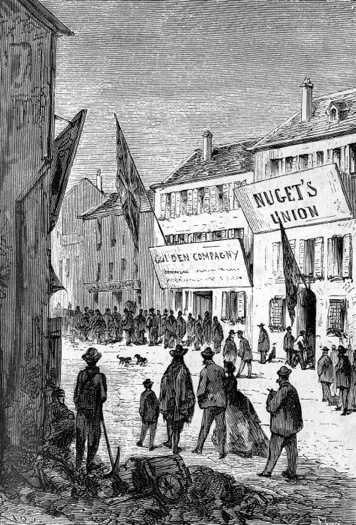

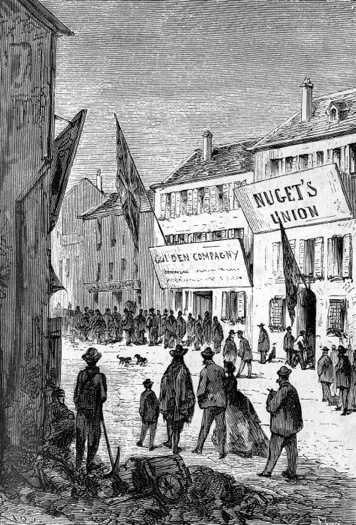

They arrived at the centre of the digging at about eleven o’clock. The travellers found themselves in a regular town, with workshops, bank, church, barracks, cottages, newspaper offices, hotels, farms, and villas. Nothing was wanting. There was even a theatre which was selling out at ten shillings a seat. They were playing a piece called Francis Obadiah, or the Lucky Digger. The hero, in the closing act, makes one last despairing stroke with his pick, and turns up a nugget of the most improbable weight.

Paganel, as usual, made himself the guide of the party

Glenarvan, who was curious to visit the vast operation of Mount Alexander, sent the wagon on under the direction of Ayrton and Mulrady, intending to rejoin them a few hours later. Paganel was delighted with this arrangement, and, as usual, made himself the guide and cicerone of the little party.

Following his advice, they first made their way toward the bank. The streets were wide. macadamized, and carefully watered. Gigantic advertisements of the “Golden Company (Limited),” “The Digger’s General Office,” and “The Nugget’s Union,” drew their gaze. The association of labour and capital had replaced the independent operations of the miner. Machines crushing quartz and washing sand could be heard everywhere.

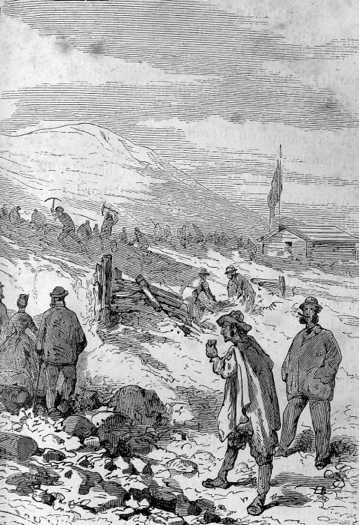

Beyond the buildings were the placers — large tracts of land being worked by the diggers — highly paid workers in the employ of the mining company. It was impossible to count the holes in the ground. The iron of their picks and spades shone in the sunlight, and flashed like lightning as stroke after stroke fell. There were men from all nations among the workers. They did not quarrel, and performed their tasks silently, as salaried people.

“You must not think, however,” said Paganel, “that there are no longer any of those feverish seekers who come to make their fortune in the game of mines on Australian soil. I know most of the diggers are hired by the companies, and they must be, as the gold fields are either sold or leased by the government. But there is one chance of getting rich still left, even if a man can neither rent nor buy.”

“What is that?” asked Lady Helena.

“The chance of ‘jumping,’” replied Paganel; “so you see we who have not the least claim here, may, perhaps, by a great deal of good luck, make our fortunes.”

“But how?” asked the Major.

“By ‘jumping’ as I have just had the honour of telling you.”

“What is ‘jumping?’” inquired MacNabbs again.

“It is a convention accepted between the miners, which often brings violence and disorder, but which the authorities could never abolish.”

“Go on, Paganel,” said MacNabbs, “you are making our mouths water.”

“Well, it is agreed that any claim which has not been worked for twenty-four hours, except on great festivals, falls into the public domain. Anyone who seizes it can dig it, and get rich, if Heaven comes to his aid. So Robert, my boy, you had best look about for one of these deserted holes, and take possession of it.”

“Monsieur Paganel,” said Mary, “don’t put such ideas into my brother’s head.”

“I am only joking, my dear Miss Mary,” said Paganel, “and Robert knows that well enough. Him a miner? Never! To dig the earth, plough it, and cultivate it, and sow seed and expect a plentiful harvest in return, is a good life; but to burrow below like moles, and about as blind, for the sake of a handful of gold, is a pitiful calling, and one must be forsaken of God and man to follow it!”

After visiting the main mine site and walking through a shipping ground, consisting largely of quartz, shale, and sand from the disintegration of the rocks, travellers arrived at the bank.

It was large building, with the Union Flag at the peak of its roof. Lord Glenarvan was received by the inspector-general, who did the honours of his establishment.

This is where the mining companies deposit gold torn from the bowels of the earth in exchange for a receipt. In the early days, the miners were exploited by the merchants of the colony. They would pay fifty-three shillings an ounce for the gold at the placer, and sell it in Melbourne for sixty-five. True, the merchants had all the risk of transporting the gold, and as highway speculators multiplied, the gold and its escort did not always arrive at its destination.

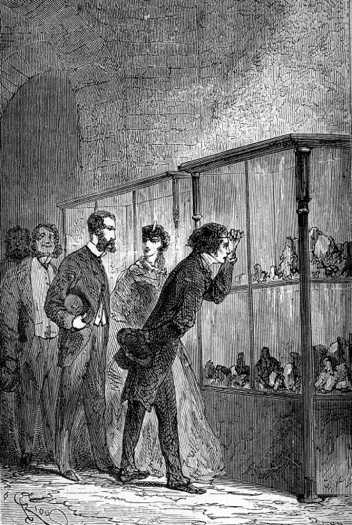

Curious specimens of gold were exhibited

Curious specimens of gold were shown to the visitors, and the inspector told them interesting details about the different methods of extracting the ore.

The precious metal is generally found in two forms: as nuggets, or finely divided residual gold. It is found as ore mixed with alluvial soil, or enclosed in its gangue of quartz. To extract it one proceeds — according to the nature of the ground — by surface, or deep excavation.

Gold nuggets are found in river beds, valleys, and ravines, sorted according to size: first the grains, then the flakes, and finally the glitter.

On the other hand, the residual gold, whose gangue has been decomposed by the action of the wind, is concentrated in patches, lying in little piles that miners call pockets. Some of these pockets contain a fortune.

At Mount Alexander, the gold collects especially in the clay layers and in the interstices of the slate rock. There are nests of nuggets where a lucky miner can lay his hands on a jackpot.

After the different specimens of ore had been inspected by the visitors, they went through the Mineralogical Museum of the bank. There they saw, classified and labelled, all the substances which compose the Australian soil. Gold is not its only treasure, for, in sober truth, the country may be called an immense treasure chest of nature, in which she has stored all her jewels. Precious and semi-precious stones sparkled in glass cases: white topaz, rivalling Brazilian topaz; almandine garnets; epidote, a beautiful green silicate crystal; rubies, represented by scarlet spinels and by a rose-coloured variety of the greatest beauty; light and dark blue sapphires, a type of corundum, and as highly esteemed as those of Malabar and Tibet; brilliant rutiles; and finally, a small diamond crystal, which was found on the banks of the Turon. Nothing was missing from this resplendent collection of gemstones, and gold for the settings was close at hand. One could hardly wish for more, unless to have found them already mounted.

Glenarvan took leave of the bank inspector with many thanks for his courtesy, which he had used extensively. The tour of the placers was resumed.

Every minute he picked up a pebble…which he examined carefully

Paganel, as detached as he was from the goods of this world, could not take a step without examining the soil. His curiosity was getting the better of him, and his companions joked with him about it. Every minute he stooped down to pick up a pebble, a piece of gangue, or fragment of quartz, which he examined carefully, and then threw away in disdain. He went on this way during the whole walk.

“Ah, Paganel?” asked the Major. “Have you lost something?”

“No doubt,” said Paganel. “We have always lost what we have not found in this country of gold and precious stones. I can’t say why, but I should like to pick up a nugget weighing a few ounces, or even twenty pounds or more.”

“What would you do with it, my good friend?” asked Glenarvan.

“Oh, I shouldn’t be troubled,” said Paganel. “I would pay tribute to my country. I would deposit it in the Banque de France.”

“Would they accept it?”

“Most certainly, in the form of railway bonds!”

They congratulated Paganel on how he intended to present his nugget to his country. Lady Helena heartily wished he might pick up the largest nugget in the world. They continued to joke with one another as they moved through the diggings. Everywhere the work was being done regularly, mechanically, and without excitement.

After a two hour walk, Paganel pointed out a decent looking inn, and proposed they should stop there and rest until it was time to rejoin the wagon. Lady Helena consented, and as it didn’t do to sit in an inn without taking refreshments, Paganel asked the innkeeper to serve them some Australian beverage.

A “nobbler” was brought for each person. The nobbler is more or less a grog, but made in reverse. Instead of a small glass of brandy being put into a large glass of water, a small glass of water was put into a large glass of brandy, with sugar. This was rather too Australian, and, to the great astonishment of the innkeeper, the nobbler was transformed into a true British grog, by the addition of a large caraffe of water.

They talked of the miners and mining. Paganel, very satisfied with what he had just seen, admitted, however, that it would have been more interesting in the first years of operation at Mount Alexander.

“The ground then,” he said, “was riddled with holes, completely overrun with legions of hard working ants, and what ants! All the immigrants were eager enough, but some had little foresight. The gold drove them to mad excesses. They drank it, they gambled it, and this inn where we are now was a ‘hell,’ in the digger’s slang. Throws of the dice led to thrusts of knives. The police were powerless, and often the governor of the colony had to call out the regular troops to put down revolts among the miners. He managed to impose order, eventually, and made each digger pay a licence, though he had some difficulty in enforcing this; yet on the whole the disorders here were smaller than in California.”

“Can anyone become a miner?” asked Lady Helena.

“Yes, Madame, you do not need a bachelor’s degree for that. Two good arms are enough. Most of the adventurers, driven from their home lands by misery, came without a penny in their pockets. The rich might have a pickaxe, or the poor, a knife. And they all brought a madness to this labour which no honest calling could have inspired.

“These gold fields presented a strange spectacle. The ground was covered with tents, tarpaulins, huts, and barracks of mud, planks, and branches. In the centre was the Marquee of the Government, with the British flag waving over it, the blue canvas tents of its agents, and the offices of the money changers, gold-buyers, and traders, who speculated on this combination of wealth and poverty. They enriched themselves, for sure.

“You should have seen the diggers, with their long beards and red woollen shirts, living in water and mud. The air was filled with the continuous noise of the pickaxes, and foul smells rising from the carcases of animals left to rot on the ground. A stifling cloud of dust covered the whole scene. The mortality rate among these unfortunate people was frightfully high, and in a less healthy climate the population would have been decimated by typhus. It would have been bad enough if all the adventurers had succeeded, but so many had no compensation for their misery. It has been estimated that for every miner who became rich, a hundred, two hundred, perhaps even a thousand, died in poverty and despair.”

“Could you tell us, Paganel, how was the gold mined?” asked Glenarvan.

“Nothing was easier,” replied Paganel. “The first miners practiced their trade as it is still done in parts of the Cevennes in France. Today the companies proceed differently. They go back to the source, itself, to the vein which produces the glitter, flakes, and nuggets. But the first miners contented themselves with washing the gold sands, that was all. They scooped out the earth, and collected that which seemed to promise gold, and used water to separate the precious particles. The washing was done by means of a machine called a ‘cradle,’ an American invention. It is a box five or six feet long, divided into two compartments. The first contains a coarse sieve laid over finer sieves. The second contained a sluice. They put the sand into the upper sieve, and pour water on it, moving it about by hand, rocking the instrument. The larger stones remained in the first sieve, the ore and the light sand in the others, according to their fineness. The earth ran off with the water through the sluice, over a series of baffles and riffles in which the gold particles collected.”

“But you still had to have one,” said John Mangles.

“It could be bought from diggers who had made their fortunes or been ruined, as the case may be. Or they could manage without it, in a pinch.”

“How?” asked Mary Grant.

“They used a pan instead, a plain iron pan, my dear Mary, and winnowed the earth like corn, only instead of grains of wheat, they sometimes found grains of gold. The first year, many a miner became rich in this simple way. Those were good times, my friends, though you’d pay 150 francs for a pair of boots, and you paid ten shillings for a glass of lemonade. The first comers always get the first pick of things. Gold was everywhere, in abundance, just lying about on the ground. Streams ran over beds of the precious metal; it was even found in the Melbourne streets: there was gold dust in the macadam. Between January 26th and February 24th, of 1852, the amount of the precious metal conveyed from Mount Alexander to Melbourne by the Government escort rose to 8,238,750 francs. That makes an average of 164,725 francs a day.5

“About as much as the civil list of the Emperor of Russia,” said Glenarvan.

“Poor man!” said the Major.

“Were there any sudden strokes of fortune?” asked Lady Helena.

“Some, Madame.”

“And you know them?” asked Glenarvan.

“Parbleu!” said Paganel. “In 1852, in the district of Ballarat, a nugget was found weighing 573 ounces; another, in Gippsland, that weighed 782 ounces; and in 1861, a ingot of 834 ounces was found. At Ballarat, again, a miner discovered a nugget that weighed 65 kilograms, which, at 1,722 francs a pound made 246,000 francs.6 A stroke of the pick which brings in 11,000 francs a year, is a good stroke indeed.”

“How much has the production of gold increased since the discovery of the mines?” asked John Mangles.

“Enormously, my dear John. At the beginning of the century there was only forty-seven million, annually, and now, including the product of the mines of Europe, Asia, and America, it is estimated at nine hundred million. Call it a billion.”

“So, Monsieur Paganel,” said young Robert. “Where we are now, under our feet, perhaps, there is a lot of gold.”

“Yes, my boy, millions! We walk on it. We look down on it. I suppose you could say we despise it.”

“This Australia is quite a privileged country, isn’t it?”

“No, Robert,” replied the geographer; “The countries with gold are by no means privileged. They breed only sluggish populations, never strong and laborious. Look at Brazil, Mexico, California, and this Australia. Where are they in this nineteenth century? The country par excellence, my boy, is not the land of gold. It is the land of iron!”7

1. 1,441 francs = $288 = £57 12s — DAS

2. Deposits of sand or gravel in the bed of a river or lake, containing particles of valuable minerals. — DAS

3. 1,577,686,950 francs. A billion and a half. ($315,537,390 — DAS)

4. However, it is possible that the emigrants were mistaken. The gold deposits are not exhausted. According to the latest news from Australia, it is estimated that the placers of Victoria and New South Wales occupy five million hectares; the approximate weight of quartz containing gold veins would be 20,550,000 kilograms, and, with the present means of exploitation, it would take the work of a hundred thousand men three centuries to deplete these placers. In sum, the gold wealth of Australia is estimated at 664,250,000,000 francs. (= $133,000,000,000 = £26,600,000,000 — DAS)

5. 8,238,750 francs = $1,647,750 = £329,550

164,725 francs = $32,945 = £6,589 — DAS.

6. 65kg = 143lb

246,000 francs = $49,200 = £9,840

7. So, I guess Australia is a privileged country, after all. It is currently one of the world’s leading producers of iron ore. (Its iron ore production is currently worth about five times as much as its gold production.)