A native child…slept peacefully

Translator’s Note:

This is the first chapter in which I was tempted to do a major rewrite of Verne’s story. It wouldn’t have been a change in any of the events, but I would have changed some of the characters’ reactions to them.

I haven’t done it, but if I did, I’d make Paganel angry about what has been done to Toliné, and not amused.

The practice of separating Aboriginal children from their families, and raising them in English religious schools was an abomination. There was nothing funny about what was done to those people.

Verne’s intent here may have been to criticize the practice through satire, as the beliefs that Toliné has been indoctrinated with are so absurd, especially considering that this was written for a French audience. But satire can be a very precarious bridge to cross, without falling off into giving the reader a very wrong impression of the author’s intent. And translating satire, which may in part be based on the language and culture of the original target audience, is especially fraught.

If this was meant as a satirical critique of the destruction of Aboriginal culture, it does get pretty much lost in translation.

— DAS

A few hills showed their profiles on the horizon at the edge of the plain, two miles from the railway. The wagon entered a succession of narrow gorges that wound capriciously up onto a low plateau, where beautiful trees — not gathered in forests, but spread out in isolated clumps — were growing with tropical luxuriance. Among the most admirable were the casuarinas, which seemed to have borrowed their robust trunk from the oak, their fragrance from the acacia, and their blue-green leaves from the pine. Their branches mingled with the elegant, slender cones of the banksia latifolia. Large shrubs with drooping branches cascaded over the edges of the plateau, like green water overflowing the rim of a basin. The eye was so bewildered with the many wonders of nature, that one hardly knew which way to look.

Ayrton, on orders from Lady Helena, stopped the wagon. The big wooden disks stopped grating over the quartz sand. Long green carpets of grass lay beneath groves of trees, divided at intervals by little mounds arranged in almost chess-board regularity.

Paganel understood this verdant solitude at a glance, so poetically laid out for eternal sleep. These were funereal squares, slowly being erased by the grass, which the traveller finds so rarely in Australia.

“The groves of the dead,” he said.

This was a native cemetery, but so green and shady, and so enlivened by the happy flocks of birds, and so engaging that it stirred no sad thoughts. It might have been gladly taken for a garden of Eden, where death was unknown. It seemed made for the living. But these tombs, kept with pious care by the aborigines, were already disappearing under a rising tide of greenery. The conquest had driven the Australians away from the land where their ancestors were resting, and colonization will soon deliver these fields of the dead to the teeth of cattle. So these groves have become rare, and how many are trod under the feet of indifferent travellers, who trample over past generations?

Paganel and Robert rode ahead of the others, exploring the small shady alleys of the tumuli. They talked and instructed each other, because the geographer maintained that he profited greatly from young Grant’s conversation. They had not gone a quarter of a mile, when Lord Glenarvan noticed them stop, dismount, and stoop down toward the ground. Judging by their expressive gestures, they were examining some very curious object.

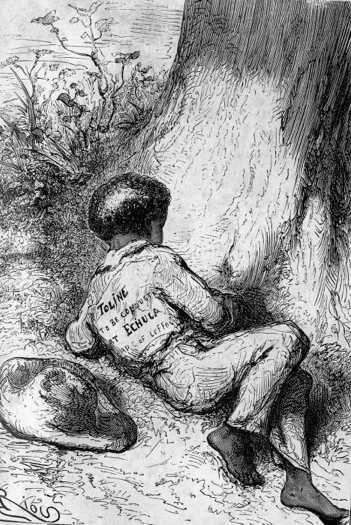

A native child…slept peacefully

Ayrton goaded his oxen into motion, and the wagon soon reached the two friends. The cause of their halt and astonishment was immediately recognized: a native child, an eight year old boy, dressed in European clothes, slept peacefully in the shade of a magnificent banksia. There was no mistaking the characteristic features of his race: the frizzy hair, the nearly black skin, the flattened nose, the thick lips, the unusual length of the arms, immediately classed him among the natives of the interior. But his face showed intelligent features, and certainly some education had relieved this young native from his low origin.

Lady Helena, very interested by this sight, got out of the wagon, followed by Mary, and presently the whole company surrounded the little native, who was sleeping soundly.

“Poor child!” said Mary Grant. “Is he lost, in this wilderness?”

“I suppose that he came a long way to visit these groves of the dead,” said Lady Helena, “Here, no doubt, rest some of those he loves.”

“But we can’t leave him here,” said Robert. “He’s alone and—”

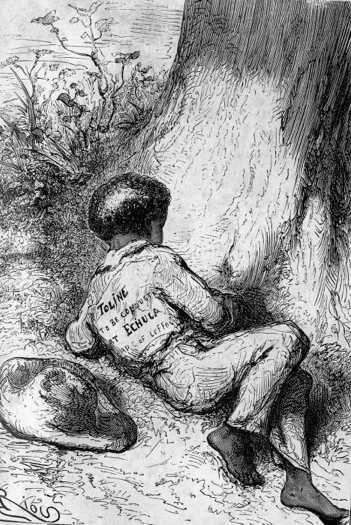

His charitable impulse was interrupted by a movement of the young native, who rolled in his sleep. Everyone was very surprised to see a sign, pinned on his shoulders.

TOLINÉ,

TO BE CONDUCTED TO ECHUCA,

CARE OF JEFFRIES SMITH, RAILWAY

PORTER. PREPAID.

“That’s the English, for you!” said Paganel. “They ship a child like a parcel! They record it as baggage! I heard it was done, but I could not believe it before!”

“Poor child!” said Lady Helena. “Could he have been in the train that derailed at Camden Bridge? Perhaps his parents were killed, and he is left alone in the world!”

“I don’t think so, Madame,” said John Mangles. “That sign indicates that he was travelling alone.”

“He’s waking up,” said Mary.

Indeed he was. Little by little, his eyes opened and closed again, pained by the glare of daylight. Lady Helena took his hand. He jumped up and looked about in astonishment at the group surrounding him. A momentary flash of fear appeared on his face, but the presence of Lady Glenarvan seemed to reassure him.

“Do you understand English, my friend?” asked the young woman.

“I understand and speak it,” replied the child, in fluent enough English, but with a marked accent, similar to a Frenchman’s.

“What is your name?” asked Lady Helena.

“Toliné,” replied the little native.

“Ah, Toliné!” exclaimed Paganel. “If I’m not mistaken, doesn’t that mean ‘tree bark’ in Australian?”

Toliné nodded, and looked around at the travellers.

“Where are you from, my friend?” asked Lady Helena.

“From Melbourne, by Sandhurst Railway.”

“Were you in that train that derailed at Camden Bridge?” asked Glenarvan.

“Yes, sir,” said Toliné. “But the God of the Bible has protected me.”

“Are you travelling alone?”

“Yes. The Reverend Paxton put me in the care of Jeffries Smith. Unfortunately, the poor factor was killed.”

“And you did not know anyone else on the train?”

“No one, sir; but God watches over children, and never forsakes them.”

Toliné said this in soft, quiet tones, which went to the heart. When he mentioned the name of God his voice was grave, and his eyes beamed with all the fervour that animated his young soul.

This religious enthusiasm at so tender an age was easily explained. The child was one of those young natives, baptized by English missionaries, and raised by them in the austere practices of the Methodist religion. His calm replies, proper behaviour, and even his sombre garb, made him look like a little Reverend already.

But where was he going all alone in these deserted regions, and why had he left Camden Bridge? Lady Helena asked him about it.

“I was returning to my tribe in Lachlan,” he said. “I want to see my family again.”

“Australians?” asked John Mangles.

“Australians from Lachlan,” said Toliné.

“Have you a father and mother?” asked Robert Grant.

“Yes, my brother.” Toliné held out his hand to young Grant, whom the epithet of “brother” affected noticeably. He embraced the little native, and it was enough to make them a pair of friends.

The entire party was was drawn into listening to the answers of the young native, and one by one they sat down around him and listened to him speak until the sun had already started to sink behind the tall trees. As this would make a good place to stop, and travelling a few more miles before sunset wouldn’t make much difference, Glenarvan gave orders to prepare their camp for the night. Ayrton unfastened the oxen, hobbled them with help from Mulrady and Wilson, and turned them loose to graze at will. The tent was pitched, and Olbinett got the supper ready. Toliné agreed to take his share, after some convincing, though he was hungry enough. He took his seat beside Robert, who picked out all the best pieces for his new friend. Toliné accepted them with a shy, charming grace.

The conversation did not languish. Everyone was interested in the child, and wanted to know his story. It was simple enough. He was one of the poor native children entrusted to the care of charitable societies by the tribes near the colony. The Australians are gentle and inoffensive. They do not profess the fierce hatred toward their conquerors which characterizes the New Zealanders, and perhaps a few of the tribes of Northern Australia. They often go to the large towns, such as Adelaide, Sydney, and Melbourne, and walk about in their very primitive costumes. They go to trade small objects of their industry: hunting and fishing implements, weapons, etc., and some tribal chiefs — from economic motives, no doubt — willingly leave their children to profit from the benefit of English education.

This was what Toliné’s parents had done. They were true Australian savages of Lachlan, a vast region lying beyond the Murray. The child had been in Melbourne for five years, and during that time had never once seen any of his family. Yet, the imperishable feeling of kindred still lived in his heart, and it was to see his tribe again, perhaps dispersed, and his family, decimated no doubt, that he had set out on this difficult journey through the wilderness.

“And after you have hugged your parents are you coming back to Melbourne?” asked Lady Glenarvan.

“Yes, Madame,” said Toliné, looking at the lady with a tender expression.

“And what are you going to be some day?”

“I want to tear my brothers out of misery and ignorance! I am going to teach them, to bring them to know and love God. I am going to be a missionary!”

These words, spoken with such animation by an eight year old child, might have provoked a laugh in light and mocking wits, but they were understood and respected by the grave Scots, who admired the religious valour of this young disciple, already prepared to fight. Even Paganel was stirred to the depths of his heart, and felt genuine sympathy awakened for the little native.

To speak the truth, until now, this savage in European attire did not much please him. He had not come to Australia to see Australians in a frock coat! He preferred them simply tattooed, and this “proper” dress baffled his preconceived notions. But as soon as Toliné had spoken so ardently, Paganel changed his opinion, and declared himself an admirer. The end of this conversation, moreover, was to make the good geographer the best friend of the Australian boy.

Toliné, in reply to a question asked by Lady Helena, said that he was studying at the Normal School in Melbourne, and that the principal was the Reverend Mr. Paxton.

“And what do you learn at this school?” asked Lady Glenarvan.

“They teach me the Bible, mathematics, geography—”

Paganel pricked up his ears at that. “Indeed! Geography?”

“Yes, sir,” said Toliné. “I even had the first prize for geography before the January holidays.”

“You had the first prize for geography, my boy?”

“Yes, sir. Here it is,” returned Toliné, pulling a book out of his pocket.

It was a well bound 32mo Bible,1. On the reverse of the first page were written the words Normal School, Melbourne. 1st First Prize for Geography, Toliné of Lachlan.

Paganel was beside himself. An Australian well versed in geography! This was marvellous, and he kissed Toliné on both cheeks, just as if he had been the Reverend Mr. Paxton himself, on the day the prize was given. Paganel, however, should have known that this is not uncommon in Australian schools. The wild youth are very apt in the geographical sciences. They learn it eagerly. On the other hand, they are perfectly averse to the science of arithmetic.

Toliné could not understand this sudden outburst of affection on the part of the Frenchman. Lady Helena had to explain that Paganel was a famous geographer and, when required, a distinguished teacher.

“A geography teacher!” said Toliné. “Oh, sir. Please test me!”

“Test you, my boy?” said Paganel. “I’d like nothing better. Indeed, I was going to do it without your leave. I should very much like to see how they teach geography in the Melbourne Normal School.”

“And suppose Toliné shows you up, Paganel?” asked MacNabbs.

“The idea!” scoffed the geographer. “Show up the Secretary of the Geographical Society of France?”

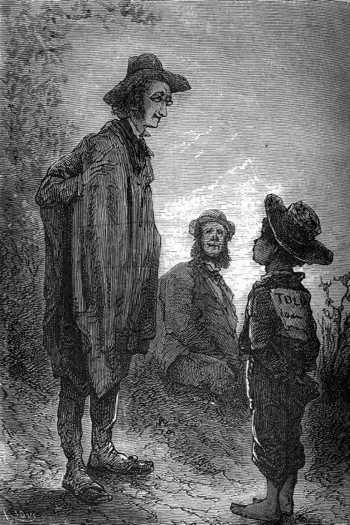

Paganel settled his spectacles firmly on his nose, straightened himself up to his full height, and put on a solemn voice becoming to a professor. He began his interrogation.

“Pupil Toliné, stand up!”

“Pupil Toliné, stand up!”

As Toliné was already standing, he could not get any higher, but he waited patiently for the geographer’s questions.

“Pupil Toliné, what are the five divisions of the globe?”

“Oceania, Asia, Africa, America, and Europe.”

“Correct. Now we’ll take Oceania first, since we are there right now. What are the principal divisions?”

“It is divided into Polynesia, Malaysia, Micronesia and Megalesia. Its main islands are Australia, which belongs to the English; New Zealand, which belongs to the English; Tasmania, which belongs to the English; the Chatham Islands, Auckland, Macquarie, Kermadec, Makin, and Maraki, which belong to the English.”

“Very good,” said Paganel. “But what of New Caledonia, the Sandwich Islands, Mendana, Pomotou?”

“These are islands placed under the Protectorate of Great Britain.”

“What?” cried Paganel, “‘Under the Protectorate of Great Britain!’ On the contrary! I rather think that France—”

“France?” said the astonished child.

“Is that what they teach you in the Melbourne Normal School?”

“Yes, Professor. Isn’t it right?”

“Oh yes, yes, perfectly right. All Oceania belongs to the English. That’s an understood thing. Let’s continue.”

Paganel’s face showed a mixture of surprise and annoyance, to the great delight of the Major.

The interrogation continued.

“Let us go on to Asia,” said the geographer.

“Asia,” said Toliné, “is an immense country. Capital: Calcutta. Main cities: Bombay, Madras, Calicut, Aden, Malacca, Singapore, Pegou, and Colombo. The Laccadive Islands, the Maldives Islands, the Chagos Islands, etc., etc. Belongs to the English.”

“Very good, pupil Toliné. And now for Africa.”

“Africa comprises two chief colonies — the Cape in the south, capital: Cape Town; and on the west the English settlements, principal city: Sierra Leone.”

“Well done!” said Paganel, beginning to enter into the spirit of this perfectly taught, but whimsically Anglo-fantastic geography. “As to Algeria, Morocco, Egypt — they are all struck out of the Britannic atlases. Let us pass on, pray, to America.”

“It is divided,” said Toliné, promptly, “into North and South America. The former belongs to the English in Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the United States, under the administration of Governor Johnson.”

“Governor Johnson,” said Paganel, “the successor of the great and good Lincoln, assassinated by a fanatical proponent of slavery! Perfect! Nothing could be better. And as to South America, with its Guyana, its Malouines, its Shetland archipelago, its Georgia, Jamaica, Trinidad, etc., etc., that belongs to the English too! I will not argue about it. But, Toliné, I should like to know your opinion of Europe, or rather your professors’.”

“Europe?” asked Toliné not at all understanding Paganel’s agitation.

“Yes, Europe! Who owns Europe?”

“Europe belongs to the English,” said Toliné, with conviction.

“I suspected it,” said Paganel. “But how? That’s what I want to know.”

“England, Ireland, Scotland, Malta, Jersey and Guernsey, the Ionian Islands, the Hebrides, the Shetlands, and the Orkneys—”

“Yes, yes, Toliné; but there are other states you forgot to mention.”

“What are they?” asked the child, not the least disconcerted.

“Spain, Russia, Austria, Prussia, France…” said Paganel.

“Those are provinces, not states,” said Toliné.

“For example?” exclaimed Paganel, tearing off his spectacles.

“Without a doubt, Spain, capital: Gibraltar.”

“Admirable! Perfect! Sublime! And France, for I am French, and I should like to know to whom I belong.”

“France,” said Toliné, quietly, “is an English province with the chief town of Calais.”

“Calais!” cried Paganel. “How? Do you think Calais still belongs to the English?”

“Without a doubt.”

“And that it is the capital of France.”

“Yes, sir; and that is where the Governor, Lord Napoleon, resides.”

At these last words Paganel collapsed in laughter. Toliné did not know what to think. He had been questioned, he had answered as best he could. But the singularity of his answers could not be attributed to him. He never imagined anything singular about them. But he did not seem disconcerted, and gravely waited the end of Paganel’s incomprehensible antics.

Major MacNabbs was laughing at Paganel. “You see. I was right. The pupil could enlighten you after all.”

“Most assuredly, Major,” said the geographer. “So that’s the way they teach geography in Melbourne! They do it well, these professors in the Normal School! Europe, Asia, Africa, America, Oceania, the whole world belongs to the English. Parbleu, with such an ingenious education it is no wonder the natives submit. Ah, well, Toliné, my boy, does the moon belong to England too?”

“It will, some day,” replied the young savage, gravely.

With that, Paganel got up. He could not sit still. He had to laugh at his ease, and he went to regain his equilibrium a quarter of a mile away from the camp.

Meanwhile, Glenarvan got out a geography text they had brought among their books. It was Samuel Richardson’s Geographical Précis, an esteemed work in England, and more knowledgeable of the science than the Melbourne teachers.

“Here, my child,” he said to Toliné. “Take this book and keep it. You have some misconceptions in geography that it is good to reform. I give it to you in memory of our meeting.”

Toliné took the book silently; but, after examining it attentively, he shook his head in disbelief, without deciding to put it in his pocket.

By this time night had closed in. It was ten o’clock in the evening, and time to think of rest if they were to start early in the morning. Robert offered his friend Toliné half his bunk, and the little fellow accepted it.

Lady Helena and Mary Grant withdrew to the wagon, and the others lay down in the tent, while Paganel’s laughter mingling with the low song of the magpies.

But at six o’clock in the morning, when the sunshine wakened the sleepers, they looked in vain for the little Australian. Toliné had disappeared. Did he want to reach the Lachlan district without delay? Was he hurt by Paganel’s laughter? No one could say.

But when Lady Helena awoke she discovered a fresh bouquet of simple green branches lying across her, and Paganel found a book in his jacket pocket: Geographical Précis by Samuel Richardson.

1. 32mo is a small pocket book size, in which one printed sheet of paper is folded five times, into 32 leaf gatherings, which are then trimmed and bound into a book, about ⅔ the size of a mass market paperback: 3½ × 5½ inches, or 9 × 14 centimetres — DAS.