They were about thirty in number

Translator’s Note:

This chapter started out pretty well, describing the genocide of the Australian Aborigines (and other indigenous peoples in other parts of the British Empire) in pretty stark language.

And then we meet some actual Aborigines, and things go rapidly down hill. I am sorely tempted to give this chapter a major rewrite, but for now, this is what it is.

I am going to be heavily annotating this chapter, and most of my annotations are not going to be relegated to the footnotes.

— DAS

The next day, January 5th, the travellers set foot in the vast territory of the Murray. This vague, uninhabited district extends as far as the lofty barriers of the Australian Alps. Civilization has not yet cut it into separate counties. It is a little known and little frequented portion of the province. Its forests will one day fall under the bushman’s axe; its prairies will be given over to the squatter’s sheep; but thus far it is virgin soil, deserted as it was the day it rose from the Indian Ocean.

These lands bear a significant name on the English maps, “Reserve for the blacks.” It is here that the natives have been brutally driven by the colonists. In the inaccessible bush of these distant plains there are marked out fixed places where the aboriginal race will gradually be extinguished. Any white man — colonist, immigrant, squatter, or bushman — may cross the limits of these reserves with impunity. The unescorted black man must never leave them.

Paganel descanted on the grave concerns of indigenous races, as he rode along. There was only one opinion in this respect, namely, that the British system led to the annihilation of conquered peoples, and their erasure from the regions in which their ancestors had lived. This fatal tendency is manifest everywhere, and in Australia more strikingly than elsewhere.

In the early days of the colony the deportees and the settlers considered the blacks to be wild animals. They hunted and shot them with rifles; they massacred them, and sought legal opinion to prove that the Australian black was outside of natural law: that the murder of these wretches was not a crime. The Sydney newspapers even proposed an expeditious way of getting rid of the Hunter Lake tribes: poison them en masse.

The English, at the beginning of their conquest, employed murder as an aid to colonization. Their cruel atrocities were numerous. They behaved in Australia as they had in India, where five million Indians have disappeared, and as they did in the Cape, where a population of one million Hottentots fell to a hundred thousand. The aboriginal population, decimated by mistreatment and drunkenness, is gradually disappearing from the continent before a homicidal civilization. Some governors, it is true, have issued decrees against the bloodthirsty bushmen. A few white men who cut off a black man’s nose and ears, or his little finger “to make a pipe cleaner,” were punished with a few lashes. This was a vain threat. Murder was organized on a vast scale, and whole tribes disappeared. In Tasmania alone, which had fifteen thousand1 natives at the beginning of the century, the native population was reduced to seven by 1863; and recently the Mercury announced the arrival of the last of the Tasmanians at Hobart.

Neither Glenarvan, the Major, nor John Mangles contradicted Paganel. Even if they had been English, they would not have defended their compatriots. The facts were self evident and indisputable.

“Fifty years ago,” said Paganel, “we would have already met many tribes of natives on our road, and up till now not a single native has come in sight. In a century this continent will be entirely depopulated of its black race.”

In fact, the reserve appeared absolutely deserted — not a trace of camps or huts. Plains and woods succeeded one another, and gradually the country became wilder. It really seemed as if not a living thing, man or beast, frequented these distant regions, when Robert stopped suddenly before a clump of eucalyptus trees.

“A monkey! There’s a monkey!” He pointed to a big black body slipping from branch to branch with surprising agility, and passing from one tree to another as if some wings supported it in the air. In this strange country did monkeys fly like the foxes to which nature has given bats’ wings?

The wagon had stopped, and everybody’s gaze was fixed on this animal, which was gradually lost in the foliage at the top of the eucalyptus trees. Soon they saw him come down again with the rapidity of lightning, run along the ground with a thousand contortions and leaps, and then catch hold of the smooth trunk of an enormous gum tree with his long arms. They could not understand how he could get up the upright, smooth tree, when there was nothing to catch hold of; but the monkey, striking the trunk alternately with a sort of hatchet, made little notches, and by these supports at regular intervals reached the fork of the gum tree. In a few seconds he disappeared in the thick foliage.

“Well, I never!” cried the Major. “Whatever sort of monkey is that?”

“That monkey,” said Paganel, “is an Australian purebred.”

The geographer’s companions had not yet had time to shrug their shoulders, when peculiar cries were heard at a little distance, something like “Coo-eeh! Coo-eeh!” Ayrton goaded on his oxen, and about a hundred paces further on the travellers came suddenly on a camp of natives.

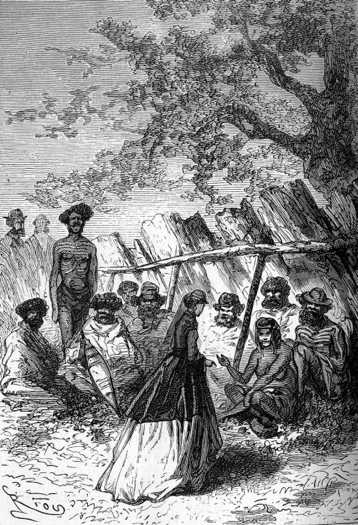

They were about thirty in number

What a sad spectacle! About ten tents were pitched on the bare ground. These “gunyos,” made with strips of bark staggered like tiles, only protect their wretched occupants on one side. These poor creatures were so degraded by misery as to be repulsive. They were about thirty men, women, and children dressed in kangaroo skins, shredded like rags. Their first impulse at the approach of the wagon was to fee, but a few words spoken in an unintelligible patois by Ayrton, appeared to reassure them. They came back with a mixture of confidence and fearfulness, like animals attracted by some tempting bait.

These natives were from five feet four to five feet seven in height, with dusky skins, not black, but the colour of old soot; woolly hair, long arms, distended abdomen, and hairy bodies, seamed by tattoo scars or incisions made in funeral ceremonies. Nothing was more horrible than their hideous faces, with enormous mouths, broad noses quite flat against the cheeks and projecting lower jaw, armed with white teeth. Never did human beings so closely approach the animal type.

“Robert was not mistaken,” said the Major, “they are monkeys; purebreds, if you like, but still monkeys.”

[Only in the sense that all men are apes, and all apes are monkeys. — DAS]

“MacNabbs,” said Lady Helena, gently, “would you side with those people, then, who hunt them down like wild beasts? The poor beings are men.”

“Men!” exclaimed MacNabbs. “At best they are but intermediate beings between man and the orangutan. If I were to measure their facial angle, I should find it exactly like a monkey’s.”

In this particular MacNabbs was right. The facial angle of an Australian aborigine is very sharp, about sixty or sixty-two degrees, equal to that of an orangutan. It was not without reason that M. de Rienzi’s proposed to class these poor wretches as a race apart, and to call them “pithecomorphs,” that is, men in the form of monkeys.

[Nineteenth century ideas about what the shape of a person’s head said about that person were complete bunkum.

[I’d like to see what MacNabbs would look like, after living in the Australian Outback for year or two. It only took a few months to kill Burke, travelling through areas which supported many bands of Aborigines. If he’d accepted the help the various bands of Aborigines he encountered offered him, he likely would have survived. — DAS]

But Lady Helena was even more right than MacNabbs, in affirming that these soul-endowed beings were human, even if of the lowest sort. Between the brute and the Australian there is an impassable chasm which separates genera. Pascal has justly said that man is not a beast. It is also true that he adds, with not less wisdom, “neither is he an angel.”

[The whole idea of “higher” and “lower” evolutionary forms is nonsense, and the Australians are just as closely related to the other great apes as all other humans. — DAS]

This latter clause of the great thinker’s proposition was certainly not true in the case of Lady Helena and Mary Grant. These two charitable women got out of the wagon, and held out their hands kindly to the poor creatures, offering them food, which the savages devoured with the most disgusting gluttony. They might very naturally have taken Lady Helena for a deity, as according to their belief, the white people were formerly black, and became white after death.

But it was the women especially who excited the pity of the fair travellers. Nothing is comparable to their condition in Australia. Nature has been a cruel stepmother to them, refusing them the slightest charm. An Australian woman is a slave, carried off by brutal violence, her only nuptial present being blows of the “waddie,” a sort of club which is never out of her master’s hand. From that moment she is struck with premature and sudden old age, she and her children are burdened with heavy labour incidental to a wandering life, carrying fishing and hunting gear, and a supply of phormium tenax from which she makes nets, wrapped in a bundle of reeds. She must find the food for her family; she hunts lizards, opossums, and snakes from the tops of the trees. She cuts the wood for the hearth, and strips off bark for the tent; a poor beast of burden, never knowing any rest, and only feeding on such revolting scraps as her master could not eat.

[My research into traditional Aboriginal life gives no indication that women were particularly poorly treated, when compared with women of Paris or London of the time, for example.

[“Waddies” are a multi-purpose tool: a hunting and war club, pestles for grinding food, for making fires, etc. They are made, and carried, by both men and women.]

Some of these unfortunate women, almost starving for food, perhaps, were trying to entice the birds with seeds.

They were seen lying on the scorching ground, motionless as if dead, waiting long hours for some unsuspecting bird to come within their reach. Their trapping technique was no more than this, and certainly only Australian birds would allow themselves to be caught in such a manner.

[Aboriginal culture has strict divisions of labour, with the men responsible for hunting larger game, while the women forage for small game, and vegetables. The women’s hunting efforts generally have a higher success rate than the men’s, and they supply most of the the band’s food. Food preparation is not an exclusively female, or male reserve, though the preparation of certain types of foods is divided between the men and women.]

The friendly advances of the travellers had tamed these savages so much that they all came around the wagon, and it had to be guarded against the native’s marauding instincts. They spoke in a whistling language, made of rhythmic beats, and made sounds resembling the cries of animals; yet their voices sometimes also had soft inflections. One word, “noki, noki,” was repeated constantly, and the gestures which accompanied it made it intelligible enough. It was, “Give me! Give me!” and referred to the most trivial articles belonging to the travellers. Mr. Olbinett had great trouble in defending his own compartment, and especially his stores of provisions. The poor famished wretches looked threateningly at the wagon, and showed their sharp teeth, which might have been exercised on human flesh. Most of the Australian tribes are not cannibals, in peacetime, but there are few savages who would hesitate to devour the flesh of a vanquished enemy.

At Lady Helena’s request, Glenarvan gave orders that some food should be distributed among them. They understood his intention quickly, and gave way to such demonstrations as would have moved the most unsympathizing heart. They roared like wild beasts, when their keeper brings their daily meal. Without conceding that the Major was right, it is impossible to deny that these aborigines border closely on animals.

Mr. Olbinett, like a gallant man, thought it only proper to serve the women first; but these poor creatures did not dare to eat before their formidable masters, who threw themselves on the biscuits and dried meat as on prey.

Mary Grant’s eyes filled with tears at the idea of her father being in the hands of such coarse wretches as these. She imagined what his sufferings must be as a slave to these wandering tribes, prey to misery, hunger, and cruel treatment. John Mangles, who was watching her with great uneasiness, divined the thoughts which filled her heart, and interpreting her wishes, questioned the quartermaster of the Britannia.

“Ayrton, was it from savages like these that you made your escape?”

“Yes, Captain,” said Ayrton. “All the tribes of the interior resemble each other. But what you see here is a mere handful of the poor devils. They are more numerous on the Darling River, and commanded by chiefs with formidable authority.”

“But what can a European do among them?” asked John Mangles.

“What I did myself,” replied Ayrton. “He goes hunting and fishing with them; he takes part in their combats. As I have told you already, he is treated according to the service he can render; and if he is at all a brave, intelligent man, he takes a position of considerable importance in the tribe.”

“But he is a prisoner,” said Mary Grant.

“And watched,” said Ayrton. “He cannot take an unobserved step, day or night.”

“Yet you managed to escape, Ayrton,” said the Major, joining in the conversation.

“Yes, Mr. MacNabbs, because of a fight between my tribe and a neighbouring people. I escaped, and I don’t regret it. But if I had to do it over again, I think I should prefer an eternal slavery to the tortures I experienced in crossing the wilderness of the interior. God keep Captain Grant from attempting such a chance of salvation!”

“Yes, certainly,” said John Mangles. “We must desire, Miss Mary, that your father is still detained by an indigenous tribe. It will be easier for us to trace him than if he were wandering over the forests of the continent.”

“You still hope, then,” said the young girl.

“I always hope, Miss Mary, to see you happy one day, with God’s help.”

Mary could only thank the young captain with her tearful eyes.

While this conversation was going on, a sudden commotion began among the savages. They uttered resounding cries; they ran about in different directions; they seized their weapons and seemed to be seized with a ferocious anger.

Glenarvan was wondering what it could all mean, when the Major asked Ayrton “You lived for a long time among the Australians. Do you understand what these fellows are saying?”

“Not quite,” said the quartermaster. “Each tribe has its own dialect. However, it seems to me that, by way of gratitude, the savages are going to show your Lordship a mock battle.”

He was correct. Without any further preamble, the savages began attacking each other with a perfectly simulated fury, so perfect, in fact, that had they not been warned, the audience would have taken this little war seriously. But explorers tell us that the Australians are excellent mimics, and on this occasion they displayed remarkable talent.

Their weapons of attack and defence consisted of a skull-cracker, a sort of wooden club, that could smash the thickest heads, and a type of tomahawk, with a sharpened stone axe head fixed between two sticks by an adhesive gum, with a ten foot handle. It is a formidable instrument in war and a useful one in peace; equally serviceable in cleaving branches and heads, in cutting bodies or trees, as the case may be.

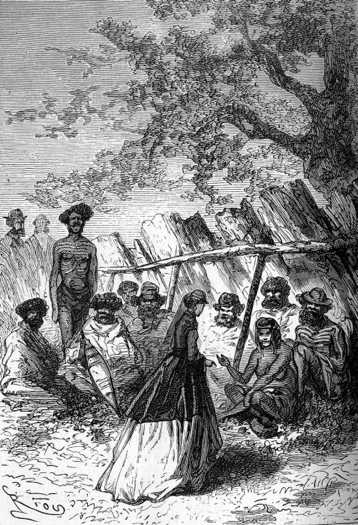

All these weapons were wielded by frenzied hands

All these weapons were wielded by frenzied hands, amidst vehement shouting. The combatants threw themselves on each other. Some would fall to the ground as if dead, and his opponent would give a yell of triumph over the conquered foe. The women, the old ones principally, possessed by the demon of war, inspired by the battle, flung themselves on the apparent corpses, and seemingly mutilated them with a ferocity which wouldn’t have been more horrible, if it been real. Lady Helena feared that the game would degenerate into a real battle. The children, too, participated with enthusiasm. Little boys, and girls especially, administered superb blows with ferocious delight.

This mock fight went on for ten minutes, when suddenly the combatants stopped. Their weapons dropped from their hands. A profound silence succeeded the noisy tumult. The natives remained fixed in their last positions, like actors in tableaux vivants. They looked petrified.

What had caused this change, and what was the secret of this sudden marble-like immobility? It was soon apparent.

A flock of cockatoos was flying over the tops of the gum trees. They filled the air with their chatter, and resembled, with the brilliant tints of their plumage, a flying rainbow. It was the appearance of this dazzling flock of birds which had interrupted the combat. The mock battle had stopped to allow for a more useful hunt.

One of the savages seized a peculiar, red painted instrument, left his still motionless companions, and went between the trees and bushes toward the flock of cockatoos. He crept along noiselessly, without even rustling a leaf or displacing a pebble; he seemed like a gliding shadow.

When he got within range, he threw his weapon horizontally, about two feet above the ground. It flew in a straight line for about forty feet, and then suddenly, without touching the ground, rose upward at a right angle to the height of a hundred feet, mortally wounding a dozen birds in its flight, and, after describing a parabola, fell again at the hunter’s feet. Glenarvan and his companions were stupefied; they could not believe their eyes.

“It’s a boomerang,” said Ayrton.

“A boomerang!” cried Paganel. “An Australian boomerang!”2

And he was off like a child to pick up the wonderful instrument, and see what was inside.

Certainly anyone would have thought that some interior mechanism, a spring suddenly released, had altered its course; but there was nothing of the kind.

The boomerang was simply a piece of smooth, hard, curved wood, thirty or forty inches long. Its breadth in the middle was about three inches, and the two ends were sharply pointed. Its concave side bent back about sixty degrees, and its convex side had the edges finely bevelled. It was as simple as it was incomprehensible.

“So this is the famous boomerang!” said Paganel, after a careful examination of the strange instrument. “A piece of wood, and nothing more. Why is it, that at a certain moment in its horizontal flight, it suddenly rises in the air, and returns to the hand that threw it? Scholars and explorers have never been able to explain this phenomenon.”

“Is it not from the same cause that makes a hoop thrown in a certain fashion come back to the point of departure?” asked John Mangles.

“Or is it a backspin effect,” asked Glenarvan, “like that of a billiard-ball struck at a certain point?”

“Not at all,” said Paganel. “In both those cases there is a point of support which determines the reaction. There is the ground for the hoop, and the baize for the billiard-ball; but here the fulcrum is missing, the instrument does not touch the ground, and yet it rises to a considerable height.”

“Then how do you explain it, Monsieur Paganel?” asked Lady Helena.

“I have no explanation, Madame, as I have already said. The effect is evidently owing to the method in which the boomerang is thrown, and its peculiar shape, but how to throw it is still a secret known only to the natives of Australia.”

“In any case, it is very ingenious … for monkeys,” added Lady Helena, looking at the Major, who shook his head with the air of a man still unconvinced.

Time was passing on, and Glenarvan felt that they ought not delay any longer. He was about to ask the ladies to resume their places in the wagon when one of the natives came running, and pronounced some words with great excitement.

“Ah,” said Ayrton, “they have caught sight of cassowaries.”

“They’re going to have a hunt?” asked Glenarvan.

“We must see that,” said Paganel. “It will be interesting. Perhaps the boomerang will be used again.”

“What do you say, Ayrton?”

“It won’t take long, My Lord,” said the quartermaster.

The natives hadn’t lost a moment. It is a stroke of good fortune for them to kill a cassowary. It secures food for the tribe for several days, so the hunters employ all their skill in trying to seize such a prize. But how, without guns, do they manage to kill, and without dogs, do they catch such an agile animal? No wonder Paganel wished to see such a novel hunt.

The emu, or uncrested-cassowary, is called mourenk by the aborigines, and is becoming rare on the Australian plains. This large bird, two and a half feet tall, has white flesh, very much like the turkey. Its eyes are light brown, and it has a downward curving black beak; the feet have three toes, armed with powerful claws; the wings, only stumps, are of no use for flight. Its plumage, resembling fur, is darker on the neck and chest. But though it cannot fly, it can run faster than the swiftest horse. They can only be caught by trickery, and and the most singular cunning.

This was why, at the call of the native, about a dozen Australians deployed like a line of skirmishers across a magnificent plain, where indigo grew naturally, and blued the ground with its flowers. The travellers stopped on the edge of a mimosa wood.

At the approach of the natives, half-a-dozen emus rose up and fled, stopping about a mile off. After observing their position, the hunter made a sign to the others to stop. They stretched themselves flat on the ground, while he drew two emus’ skins, very skilfully sewn together, out of his net and put them on. He held his right arm over his head, and his movements were an exact imitation of an emu looking for food.

He made his way gradually toward the birds, occasionally stopping, and pretending to pick up a few seeds, and sometimes kicking up a cloud of dust around him. All his manoeuvres were perfectly executed. Nothing could be a more faithful reproduction of the motions of the emu. Every now and then he gave a deep croak, which deceived the birds themselves. The savage was soon in the midst of his unsuspecting prey. Suddenly he lifted his club, and killed five or six of the emus on the spot.

The hunter had succeeded, and the stalk was over.

Glenarvan and his party took leave of the natives at once, and started onward. The savages displayed no regret at parting. Perhaps the result of the cassowary hunt had made them forget their satisfied hunger. They did not even show the gratitude of the stomach, more lasting than that of the heart, in the uncultivated natures of savages.

Be that as it may, one could not but admire their intelligence and their skill.

“Now, my dear MacNabbs,” said Lady Helena, “you are surely willing to admit that the Australians are not monkeys.”

“Because they faithfully imitate the behaviour of an animal?” said the Major. “On the contrary, that would justify my doctrine!”

“Jesting is no answer,” returned Lady Helena. “I mean to make you give up your opinion, Major.”

“All right. Well, yes, my cousin, or rather, no. The Australians are not monkeys; it is the monkeys that are Australians.”

“What do you mean?”

“Do you know what the negroes say about that interesting race, the orangutans?”

“What do they claim?”

“They declare,” replied the Major, “that the monkeys are blacks like themselves, but more clever. ‘He no speak because he no want to work,’ said a negro of a tame orangutan that his master kept as a pet.”

1. Verne puts the pre-European indigenous population of Tasmania at 500,000, which is about two orders of magnitude too high. The entire pre-European indigenous population of Australia is estimated to be between 315,000 and 750,000 people. Tasmania’s population is estimated to have been between 2,000 and 15,000. They were pretty much extinct by 1866.

2. Boomerangs used for hunting are made to fly straight. Boomerangs that curve in flight are made as toys for recreation. (And now, to sell to tourists.) — DAS