Paganel had the first watch

On January 6th, at seven o’clock in the morning, after a tranquil night passed in longitude 146° 15′, the travellers continued their journey across the vast district. They walked steadily toward the rising sun, and their tracks marked a straight path across the plain. Twice they came upon the traces of squatters going north, and their different footprints would have became confused, if not for the double clover Black Point mark Glenarvan’s horse left in the dust.

The plain was sometimes crisscrossed by capricious creeks, surrounded by boxwood, and whose waters only flowed intermittently. They originated on the slopes of the Buffalo Ranges, a chain of mountains of moderate height, whose picturesque line undulated on the horizon.

It was decided to press on to the mountains before camping that evening. Ayrton goaded on his team, and after a journey of thirty-five miles, the somewhat fatigued oxen arrived at the foothills. The tent was pitched beneath tall trees, and supper quickly served as night closed in. There was less thought of eating than of sleeping, after such a march.

Paganel had the first watch

Paganel, who had the first watch, did not lie down, but shouldered his rifle and walked up and down before the camp, to keep himself from going to sleep.

In spite of the absence of the moon, the night was almost luminous under the glare of the southern constellations. The scholar amused himself by reading the great book of the firmament, a book which is always open, and full of interest to those who can understand it. The profound silence of sleeping nature was only interrupted by the clanking of the fetters on the horses’ feet.

Paganel allowed himself to be drawn into his astronomical meditations, and was more occupied with the things of heaven than with things of the earth, when a distant sound drew him from his reverie.

He listened attentively, and to his great astonishment, he thought he heard the sounds of a piano. A few chords, in arpeggiated movements, came to his ears. He could not be wrong.

“A piano in the wilderness!” thought Paganel. “I don't believe it!”

It was very surprising, indeed, and Paganel preferred to believe that some strange Australian bird was imitating the sounds of a Pleyel or Erard, as others imitate the sounds of a clock or mill.

But at this moment, a pure, ringing, voice rose on the air. The pianist was accompanied by a singer. Still Paganel was unwilling to be convinced. But after a few moments he was forced to concede that he was listening to the sublime strains of Mozart’s “II mio tesoro tanto” from Don Juan.

“Parbleu!” thought the geographer. “As strange as the Australian birds are, and even granting that parrots are the most musical birds in the world, they can’t sing Mozart!”

He listened to the end of this sublime inspiration of the master. The effect of this sweet melody on the still clear night was indescribable. Paganel remained spell-bound for a time; then the voice went quiet, and everything returned to silence.

When Wilson came to relieve Paganel on watch, he found the geographer plunged into a deep reverie. Paganel said nothing to the sailor, but reserved his information for Glenarvan in the morning, and went to snuggle into his bed in the tent.

Next day, the whole troop was awakened by unexpected barking. Glenarvan got up immediately. Two magnificent pointers, standing tall, admirable specimens of the English breed, were frolicking on the edge of a little wood. At the approach of the travellers, they retreated into the trees, redoubling their clamour.

“There is a station in this wilderness,” said Glenarvan, “and hunters, since these are hunting dogs.”

Paganel was already opening his mouth to recount his nocturnal experience, when two young men appeared, mounted on two beautiful purebred horses, true “hunters.”

The two gentlemen, dressed in elegant hunting costume, stopped at the sight of the little troop camped in such bohemian manner. They seemed to be wondering what the presence of armed men in this place meant when they saw the ladies get out of the wagon. They dismounted instantly, and went toward them, hat in hand.

Lord Glenarvan came to meet them, and as a stranger, announced his name and rank. The gentlemen bowed.

“My Lord,” said the elder, “will not these ladies, your companions, and yourself, honour us by resting a little beneath our roof?”

“Gentlemen…?” said Glenarvan.

“Michael and Sandy Patterson, proprietors of Hotham Station1. You are already on our land, and our house is scarcely a quarter of a mile distant.”

“Gentlemen,” said Glenarvan, “I should not like to abuse such graciously offered hospitality.”

“My Lord,” said Michael Patterson, “by accepting it, you will confer a favour on poor exiles, who will be only too happy to do the honours of the station.”

Glenarvan bowed in token of acquiescence.

“Sir,’’ said Paganel, addressing Michael Patterson, “would I be indiscreet in asking if it was you who sang an air from the divine Mozart last night?”

“It was, sir,” replied the stranger, “and my cousin Sandy accompanied me.”

“Well, sir.” Paganel held out his hand to the young man. “Receive the sincere compliments of a Frenchman, who is a passionate admirer of this music.”

Michael grasped his hand cordially, and then indicated the road to follow. The horses were left in the care of Ayrton and the sailors. The two young men guided the party on foot, chatting and admiring, to Hotham Station.

It was truly a magnificent establishment, kept as scrupulously in order as an English park. Immense meadows, enclosed in grey fences, stretched away out of sight. Thousands of oxen and millions of sheep grazed there, tended by numerous shepherds, and still more numerous dogs. The crack of the stockwhip mingled continually with the barking of the dogs and the bellowing and bleating of the cattle and sheep.

Toward the east there was a boundary of myalls and gum trees, behind which rose the majestic peak Mount Hotham, 6,100 feet high. Long avenues of evergreen trees radiated in all directions. Here and there massed thickets of “grass trees,” ten foot tall shrubs, similar to the dwarf palm, crowned with tufts of long narrow leaves. The air was perfumed with the scent of laurel-mints, whose white blossoms, now in full bloom, gave off the finest aromatic scents.

To these charming groups of native trees were added transplants from European climates. There were peach, pear, and apple trees. The travellers were delighted by figs, oranges, and even oaks, and greeted them with loud hurrahs! But astonished as the travellers were to find themselves walking beneath the shadow of the trees of their own country, they were still more so at the sight of the birds that flew about in the branches. The satin bird, with its silky plumage, and the sericulus with their gold and black velvet plumage.

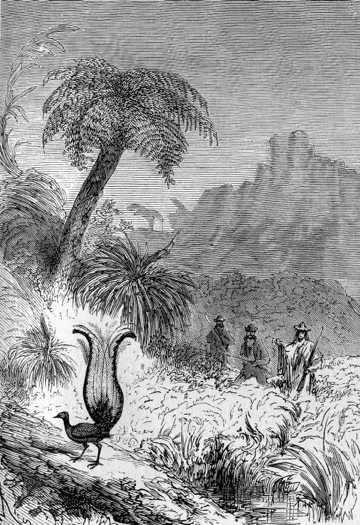

The “menure,” or lyre bird

For the first time, too, they saw here the “menure,” or lyre bird, the tail of which resembles in form the graceful instrument of Orpheus. It flew about among the tree ferns, and when its tail struck the branches, they were almost surprised not to hear the harmonious strains that inspired Amphion to rebuild the walls of Thebes. Paganel had a great desire to play on it.

Lord Glenarvan was not satisfied with admiring the fairy-like wonders of this oasis, improvised in the Australian wilderness. He was listening to the history of the young gentlemen. In England, in the midst of civilized campaigns, the newcomer acquaints his host whence he comes and whither he is going; but here, by a nuance of delicacy, Michael and Sandy Patterson thought it best to make themselves known to the travellers to whom they had offered hospitality. They told their story.

It was that of two young Englishmen, intelligent and industrious, who did not believe that being born wealthy dispensed with the need to work. Michael and Sandy Patterson were the sons of London bankers. At twenty, the head of their family said “Here are some millions, young men. Go to a distant colony, and start some useful settlement there. Learn to know life by labour. If you succeed, so much the better. If you fail, it won’t matter much. We shall not regret the millions that have served to make you men.” The two young men obeyed. They chose the colony of Victoria in Australia as the field for sowing the paternal bank-notes, and had no reason to repent the selection. At the end of three years the station was flourishing.

There are more than three thousand stations in Victoria, New South Wales, and South Australia. Some run by squatters who rear cattle, and others by settlers who cultivate the soil. Until the arrival of the two Pattersons, the largest station of this sort was that of Mr. Jamieson, which covered a hundred square kilometres, and ran for twenty-five kilometres2 along the Peroo River, one of the tributaries of the Darling.

Hotham Station was now larger, and more prosperous. The young men were both squatters and settlers. They managed their immense property with rare ability and uncommon energy.

The station was far from the principal towns in the midst of the uncrowded wilds of the Murray. It occupied the area between 146° 48′ and 147°, a long wide space five leagues in extent, lying between the Buffalo Ranges and Mount Hotham. At the two northern angles of this vast quadrilateral stood Mount Aberdeen3 on the left, and the peaks of High Barven on the right. It was well watered by beautiful winding streams, thanks to the creeks and tributaries of the Oven’s River, which flows north into the Murray. They were equally successful in the breeding of cattle, and the cultivation of the land. Ten thousand acres of ground, excellently tilled and planted, mingled native crops with exotic produce, while millions of animals fattened in the fertile pastures. The products of Hotham Station fetched a high price in the markets of Castlemaine and Melbourne.

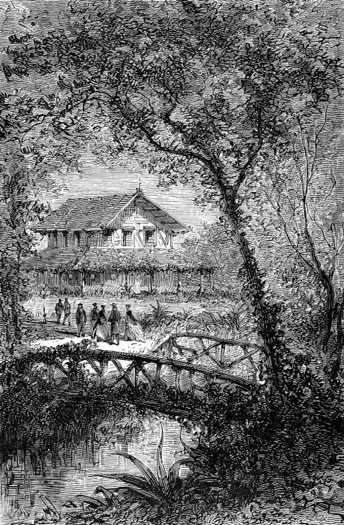

Michael and Sandy Patterson had just concluded these details of their busy life, when their home came in sight, at the end of an avenue of casuarinas.

It was a charming house, built of wood and brick

It was a charming house, built of wood and brick, hidden in a eucalyptus grove. It was in the elegant form of a chalet, surrounded by a verandah, with Chinese lamps hanging around the walls. Multi-coloured awnings unfolded over the windows, like flowers in bloom. Nothing could be more charming or exquisite, and at the same time nothing more comfortable. On the lawns, and in the clumps of trees round about, were bronze candelabras which supported elegant lanterns. At nightfall the whole of the park was lighted with white gas lights, supplied from a small gasometer, hidden under the cradles of myalls and tree-ferns.

There was nothing that indicated a working station. No sheds, stables, or bunkhouses. All these out-buildings — a veritable village of more than twenty huts and houses — were about a quarter of a mile off, at the bottom of a small valley. Electric telegraph wires connected the village and the masters’ house, which, far removed from all noise, seemed lost in a forest of exotic trees.

They passed along the casuarinas avenue. A small, extremely elegant, iron bridge across a murmuring creek formed the entrance to the private grounds. This was quickly crossed. A steward of high mien came out to meet the travellers, the doors of the house opened, and the hosts of Hotham Station conducted their guests into the sumptuous apartments contained within this envelope of brick and flowers.

All the luxury of artistic and fashionable life was offered to them. The antechamber, decorated with trophies of the turf and the hunt, opened into a large salon with five windows. There was a piano covered with classical and modern music, easels carrying rough canvases, pedestals adorned with marble statues, pictures by Flemish masters on the walls, rich carpets as soft on the feet as thick grass, tapestries brightened with graceful mythological scenes, an antique chandelier suspended from the ceiling, precious porcelain, priceless knick-knacks of perfect taste, a thousand dear and delicate things which were astonishing to see in an Australian house, made a perfect picture of artistic comfort. Everything that could charm the troubles of a voluntary exile, all that could bring back the remembrance of European habits, furnished this fairy salon. One might have thought himself in some castle in France or England.

The five windows let in daylight, softened by the shade of the veranda, and the thin fabric of the awnings. Lady Helena was quite amazed as she went toward them. The view from this side of the house extended over a wide valley, to the feet of the eastern mountains. The succession of meadows and woods, vast clearings, and the graceful outlines of the hills, made a spectacle beyond all description. No other country in the world could compare with it, not even the famous Paradise Valley, in Norway’s Telemark. This vast panorama, with its great patches of light and shade, changed every hour with the caprices of the sun. Imagination could dream of nothing finer, and this enchanting view satisfied all the appetites of the eye.

On an order from Sandy Patterson, the butler of the station improvised a lunch. In less than a quarter of an hour the travellers sat at a sumptuously served table. The quality of the food and wine was indisputable, but what pleased the guests most of all amidst these refinements of opulence, was the joy of the young squatters, happy to offer this splendid hospitality under their roof.

It was not long before they were told the history of the expedition, and took a keen interest in Glenarvan’s search. They also gave hope to the captain’s children.

“Harry Grant,” said Michel, “has obviously fallen into the hands of the natives, since he has not reappeared at any of the settlements on the coast. He knows his position exactly, as the document proves, and the reason he did not reach some English colony is that he must have been taken prisoner by the savages the moment he landed.”

“That is precisely what befell his quartermaster, Ayrton,” said John Mangles.

“But you, gentlemen,” asked Lady Helena, “have you never heard of the Britannia disaster?”

“Never, Madame,” said Michael.

“And what treatment, in your opinion, has Captain Grant met with among the natives?”

“The Australians are not cruel, Madame,” replied the young squatter, “and Miss Grant may be reassured on that score. There are frequent examples of the gentleness of their nature, and some Europeans have lived a long time amongst them without having the least cause to complain of their brutality.”

“King, amongst others, the sole survivor of the Burke expedition,” said Paganel.

“And not only that brave explorer,” said Sandy, “but also an English prisoner named Buckley. He escaped in 1803, on the coast of Port Philip, was collected by the natives, and lived for thirty-three years among them.”

“And more recently,” added Michael, “one of the latest issues of Australasian informs us that a man named Morrill has just been restored to his countrymen after sixteen years of captivity. His story is very similar to the captain’s, for it was at the time of his shipwreck in the Peruvian, in 1846, that he was made prisoner by the natives, and dragged away into the interior of the continent. So, I think you have to keep all hope.”

The young squatter’s words caused great joy to his listeners. They corroborated the opinions already given by Paganel and Ayrton.

The conversation turned to the convicts, after the ladies had left the table. The squatters had heard of the disaster at Camden Bridge, but felt no concern about the escaped gang. The criminals would not dare attack a station of more than a hundred men. Besides, they would never go into the wilderness of the Murray, where they could find no booty, nor near the colonies of New South Wales, where the roads were too well watched. Ayrton had expressed similar views.

Glenarvan could not refuse the request of his amiable hosts to spend the whole day at Hotham Station. It was twelve hours’ delay, but also twelve hours’ rest, and both horses and oxen would recuperate well in the comfortable stables they would find there.

This was agreed upon, and the two young men submitted to their guests a programme of the day, which was eagerly adopted.

At noon, seven vigorous hunters were pawing at the gates. An elegant brake was ready for the ladies, in which a coachman could exhibit his skill in driving four-in-hand. The riders, preceded by outriders armed with excellent shotguns, were in their saddles, and galloped out the gates, followed by a pack of pointers barking joyously as they bounded through the bushes.

For four hours the cavalcade traversed the paths and avenues of the park, which was as large as a small German state. The Reuiss-Schleitz, or Saxe-Coburg Gotha, would have fit inside it comfortably. They met few people, but sheep abounded. As for game, an army of beaters could not have thrown more before the rifles of the hunters. The noisy reports of guns were soon heard on all sides. Young Robert did wonders next to Major MacNabbs. The daring boy, in spite of his sister’s injunctions, was always in front, and the first to fire. But John Mangles promised to watch over him, and Mary felt less concerned.

During this hunt they killed certain animals peculiar to the country, which Paganel had previously only known by name: amongst others the “wombat” and the “bandicoot.”

The wombat is an herbivorous animal, which burrows in the ground like a badger. It is as large as a sheep, and the flesh is excellent.

The bandicoot is a species of marsupial which could outwit the European fox, and give him lessons in pillaging poultry yards. It was a repulsive looking animal, a foot and a half long, but as Paganel chanced to kill it, of course he thought it charming. “An adorable creature,” he called it.

Robert, in addition to game, skilfully killed a Dasyurus maculatus, or “tiger quoll,” a sort of small fox, whose black fur, spotted with white, is as valuable as the marten’s; and a couple of opossums, who were hiding among the thick foliage of the large trees.

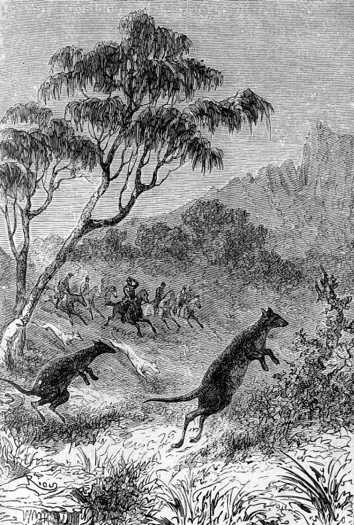

The dogs roused a band of kangaroos

But the most interesting event of the day by far was the kangaroo hunt. About four o’clock, the dogs roused a band of these curious marsupials. The little ones retreated back into their maternal pouches, and the whole mob escaped in file. Nothing is more astonishing than the enormous bounds of the kangaroo. The hind legs of the animal are twice as long as the front ones, and unbend like a spring.

At the head of the flying mob was a male five feet high, a magnificent specimen of the Macropus giganteus. An “old man,” as the bushmen say.

The chase was vigorously pursued for four or five miles. The kangaroos showed no signs of weariness, and the dogs — who had reason enough to fear their strong paws armed with a sharp claw — did not care to approach them. But at last worn out with the race, the troop stopped, and the “old man” leaned against the trunk of a tree ready to defend himself. One of the pointers, carried away by excitement, went up to him. A moment later the unfortunate dog leapt into the air, and fell back, disemboweled. The whole pack would not have got the better of these powerful marsupials. They had to finish the fellow with rifle shots. Nothing but bullets could bring down the gigantic animal.

Robert almost fell victim of his own imprudence. To make sure of his aim, he had approached too near the kangaroo, and the animal leaped upon him immediately. Robert fell; a cry was heard. Mary Grant saw it all from the brake, and in an agony of terror, speechless, and almost unable even to see, stretched out her arms toward her little brother. No one dared to fire, for fear of wounding the child.

John Mangles pulled out his hunting knife, and at the risk of being disemboweled, rushed at the animal, and plunged his knife into its heart. The beast dropped, and Robert rose, unhurt. A moment later he was in his sister’s arms.

“Thank you, Mr. John! Thank you!” she said, holding out her hand to the young captain.

“I had pledged myself to his safety,” was all John said, taking her trembling fingers in his own.

This incident ended the hunt. The mob of marsupials had disappeared after the death of their leader, whose remains were brought back to the house. It was then six o’clock. A magnificent dinner was waiting for them. Among other dishes, a kangaroo tail soup, prepared in the native fashion, was the great success of the meal.

After the ice cream and sorbets of the dessert, the guests passed into the living room. The evening was devoted to music. Lady Helena, who was a very good pianist, put her talents at the disposal of the squatters. Michael and Sandy Patterson sang with perfect pitch passages borrowed from the latest scores of Gounod, Victor Massé, Félicien David, and even of that misunderstood genius, Richard Wagner.

Tea was served at eleven o'clock. It was made with that English perfection that no other people can match. Paganel, having asked to taste Australian tea, was brought a black, inky liquor: a liter of water in which half a pound of tea had boiled for four hours. Paganel, in spite of his grimaces, declared this drink excellent.

At midnight the guests were conducted to cool, comfortable rooms, where they prolonged in their dreams the pleasures of the day.

Next morning, at dawn, they took leave of the two young squatters, with hearty thanks and a promise from them of a visit to Malcolm Castle when they should return to Europe. Then the wagon began to move away, around the foot of Mount Hotham, and soon the hospitable dwelling disappeared from the sight of the travellers like some brief vision which had come and gone.

For five miles further the horses were still treading the station lands. It was not until nine o’clock that they had passed the last fence, and entered the almost unknown districts of the province of Victoria.

1. Verne has “Hottam” Station, but as it’s named after a real place, Mount Hotham, I changed it. I also reduced Mount Hotham’s stated height to match reality. — DAS

2. An area of thirty-seven square miles, with a sixteen mile border on the Peroo — DAS

3. Now named Mount Buffalo — DAS