A hail-storm of extreme violence assailed the travellers

An immense barrier lay across the route to the southeast. It was the Australian Alps, a vast fortification, whose capricious curtains extended fifteen hundred miles, and pierced the clouds at the height of four thousand feet.

A subdued heat reached the ground through the veil of cloud in the overcast sky. The temperature was moderate, but the rough road made travel difficult. The undulations of the plain became more and more pronounced. Several hills covered with young, green, gum trees appeared here and there. Further on these sharply rising foothills formed the first echelons of the great Alps. Their course became a continual ascent, which put a greater strain on the oxen dragging along the cumbersome wagon. Their yokes creaked, they blew loudly, and the muscles of their hocks were stretched nearly to breaking. The planks of the vehicle groaned at the unexpected jolts that Ayrton, with all his skill, could not prevent. The ladies bore these difficulties cheerfully.

John Mangles and his two sailors acted as scouts, and went about a hundred paces ahead. They chose practicable paths, not to say passes, for these hills had many pitfalls, which the wagon had to steer carefully between. It required careful navigation to find a safe way through this rugged terrain.

It was a difficult and often perilous task. Wilson’s axe was needed many times to open a passage through thick tangles of shrubs. The damp clay soil gave way under their feet. A thousand detours around insurmountable obstacles — huge blocks of granite, deep ravines, or suspicious lakes — extended their journey. When night came they found they had only made half a degree’s progress. They camped at the foot of the Alps, on the banks of Cobungra Creek, on the edge of a small plain covered with four foot shrubs whose bright red leaves gladdened their eyes.

“It will be hard work getting over those,” said Glenarvan, looking at the silhouettes of the mountains, fading away in the deepening darkness. “Alps! The name has sobering connotations.”

“It is not quite as bad as it sounds, my dear Glenarvan,” said Paganel. “You do not have an entire Switzerland to cross. In Australia, there are the Grampians, Pyrenees, Alps, and Blue Mountains, just as in Europe and America, but in miniature. This simply demonstrates that the imagination of geographers is not infinite, or that their vocabulary of proper names is very poor.”

“So, these Australian Alps?” asked Lady Helena.

“Mere pocket mountains,” said Paganel; “we shall cross them without noticing.”

“Speak for yourself,” said the Major. “I only know of one man who is so distracted that he could cross over a chain of mountains and not know it.”

“Distracted!” said Paganel. “But I am not distracted, anymore. I appeal to the ladies. Since I set foot on Australia, have I not kept my promise? Have I been distracted even once? Can you name a single blunder?”

“Not one, Monsieur Paganel,” said Mary Grant. “You are now the most perfect of men.”

“Too perfect,” laughed Lady Helena. “Your distractions suited you admirably.”

“Didn’t they, Madame? If I have no faults now, I shall soon be like everyone else. I hope that before long I will commit some good blunder which will give you a good laugh. It seems to me that I fail in my vocation, if I’m not making mistakes.”

Next day, January 9th, the little troop ascended the alpine pass with great difficulty, despite the assurances of the confident geographer. It was necessary to hunt for a clear path, and to enter the depths of narrow gorges that could terminate in dead ends.

Ayrton would have been very much embarrassed, if, after an hour’s march, an inn, a miserable “tap” hadn’t unexpectedly presented itself on one of the mountain paths.

“Parbleu!” cried Paganel. “The landlord of this tavern won’t make his fortune in a place like this. What is the use of it here?”

“To give us the information we need,” said Glenarvan. “Let us go in.”

Glenarvan, followed by Ayrton, crossed the threshold of the inn. The landlord of the Bush Inn, as it’s sign proclaimed, was a coarse man with an ill-tempered face, who must have considered himself his principal customer for the gin, brandy, and whiskey he had to sell. He seldom saw anyone but squatters and drovers.

He answered all the questions put to him in a surly tone, but his replies sufficed to make the route clear to Ayrton. Glenarvan rewarded him with a handful of crowns for his trouble, and was about to leave the tavern, when a placard against the wall arrested his attention.

It was a notice from the colonial police. It announced the escape of the convicts from Perth, and offered a reward of £100 for the capture of Ben Joyce.

“He’s certainly a fellow that’s worth hanging,” said Glenarvan to the quartermaster.

“And worth capturing still more,” said Ayrton. “One hundred pounds! What a sum! He’s not worth it!”

“As to the innkeeper,” said Glenarvan, “he does not reassure me, notwithstanding his sign.”

“Me neither,” said Ayrton.

They went back to the wagon. They made their way to the end of the Lucknow road: a narrow path that snaked its way up the pass in a series of switchbacks. They started the climb.

It was a painful ascent. More than once both the ladies and gentlemen had to get down and walk. It was necessary to help move the heavy wagon by pushing on its wheels, and to support it on dangerous gradients; to unharness the oxen when the wagon’s steering gear couldn’t handle the sharp turns, and chock the wheels when the wagon threatened to roll back. More than once Ayrton had to reinforce his oxen by harnessing the horses, already tired with dragging themselves along.

Whether it was this prolonged fatigue, or from some other cause, one of the horses suddenly died, without the slightest warning or symptom of illness. It was Mulrady’s horse that fell, and when he tried to rouse it, he was surprised to find it deceased.

Ayrton came to examine the animal lying on the ground, but was at a loss to explain this sudden death.

“The beast must have broken some blood-vessel,” said Glenarvan.

“Evidently,” said Ayrton.

“Take my horse, Mulrady,” said Glenarvan. “I will join Lady Helena in the wagon.”

Mulrady obeyed, and the little party continued their exhausting ascent, leaving the carcass of the dead animal to the ravens.

The Australian Alps range is shallow, and the base is not more than eight miles wide. If the pass chosen by Ayrton came out on the eastern side, they might hope to get over the high barrier within another forty-eight hours. This was the last barrier, and once surmounted, it would be an easy road to the sea.

They reached the highest point of the pass, about two thousand feet, on January 10th. They came out on an open plateau, with nothing to block the view. Toward the north the quiet waters of of Lake Omeo glittered in the sunlight, dotted with waterfowl, and beyond lay the vast plains of the Murray. To the south stretched the green plains of Gippsland, with its rich gold fields and tall forests. It was still a wild country, where nature was still mistress of her resources, and the courses of her rivers. The great trees had not yet felt the woodman’s axe, and the rare squatters had not yet overcome her. It seemed as if this chain of the Alps separated two different countries, one of which had retained its primitive wildness.

The sun was setting, and a few rays piercing the reddened clouds highlighted the hues of the Murray district. On the other side of the mountains, Gippsland fell into deep shadow, as if night had suddenly fallen on the whole region. The contrast between these two countries was sharply felt by the spectators as they contemplated the almost unknown district that they were about to cross to the Victorian frontier.

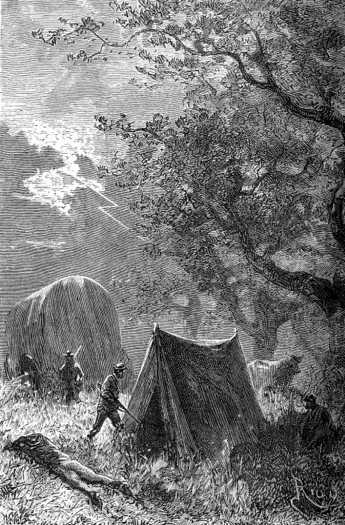

A hail-storm of extreme violence assailed the travellers

They camped on the plateau that night, and began the descent the next day. They made good progress until an extremely violent hail storm assailed the travellers, and forced them to seek a shelter among the rocks. It was not hail stones, but regular lumps of ice, as large as one’s hand, which fell from the stormy clouds. A sling could not have thrown them with more force, and some good bruises taught Paganel and Robert that they had to stay under shelter. The wagon was riddled in several places, and few roofs could have held out against those sharp icicles, some of which had impaled themselves into the trunks of the trees. It was impossible to go on until this tremendous shower was over, unless the travellers wished to be stoned. It lasted about an hour, and then the march began again over slanting rocks still slippery after the hail.

Toward evening the wagon, very much shaken and disjointed in several places, but still standing firm on its wooden wheels, came down the last slopes of the Alps, between large isolated pines. The pass ended in the plains of Gippsland. The chain of the Alps was safely passed, and the usual arrangements were made for the nightly encampment.

On the 12th at daybreak, the journey was resumed with an ardour which never relaxed. Everyone was eager to reach the goal — that is to say, the Pacific Ocean — at the place where the wreck of the Britannia had occurred. Only there could the search really begin for the traces of the shipwrecked sailors, and not in these deserted regions of Gippsland. Ayrton again urged Lord Glenarvan to send orders for the Duncan to proceed to the coast, in order to have at hand all possible resources for the search. He thought it would be advisable to take advantage of the Lucknow road to Melbourne. It they waited it would be difficult to find any way of direct communication with the capital.

The quartermaster’s recommendation seemed sound, and Paganel concurred. He also thought that the presence of the yacht would be very useful, and he added that it would no longer be possible to communicate with Melbourne, once they left the Lucknow road.

Glenarvan was undecided about what to do, and perhaps he would have yielded to Ayrton’s arguments, if the Major had not vigorously disagreed. He maintained that the presence of Ayrton was necessary to the expedition, that he would know the country about the coast, and that if any chance should put them on the track of Harry Grant, the quartermaster would be better able to follow it up than anyone else, and, finally, that he alone could point out the exact spot where the Britannia had been lost.

MacNabbs urged for the continuation of the journey, without making any change in their programme. He found an ally in John Mangles, who agreed with him. The young captain even remarked that orders could reach the Duncan more easily from Twofold Bay, than if a messenger was sent two hundred miles through wild country. MacNabbs arguments prevailed. It was decided that they would wait until they came to Twofold Bay. The Major watched Ayrton closely, and noticed his disappointed look. But he said nothing, keeping his observations, as usual, to himself.

The plains which lay at the foot of the Australian Alps were level, but gently sloping toward the east. Large clumps of mimosas, eucalyptus, and numerous varieties gum trees, broke the uniform monotony. Gastrolobium grandiflorum covered the ground, with its bushes covered with gay flowers. Several unimportant creeks, mere streams full of little rushes, and overgrown with orchids, often interrupted the route. They were forded. Flocks of bustards and emus fled at the approach of the travellers. Kangaroos leapt and sprang over the shrubs like elastic puppets. But the hunters of the party scarcely thought of hunting, and the horses didn’t need the extra work.

A sultry heat weighed on the country. The atmosphere was saturated with electricity, and its influence was felt by men and beasts. They dragged themselves along, and cared for nothing else. The silence was only interrupted by the cries of Ayrton urging on his burdened team.

From noon to two o’clock they went through a curious forest of ferns, which would have excited the admiration of less weary travellers. These plants in full bloom were up to thirty feet high. Horses and riders passed easily beneath their drooping leaves, and sometimes the wheel of a spur resounded on striking their woody stems. Beneath these still parasols there was a refreshing coolness which everyone appreciated. Jacques Paganel, always demonstrative, gave such deep sighs of satisfaction that the parakeets and cockatoos flew out in alarm, making a deafening chorus of noisy chatter.

The geographer was going on with his sighs and jubilations, when his companions saw him suddenly tottering on his horse, and falling down in a lump. Was it some dizzy spell, or even a stroke, caused by the high temperature? They ran to him.

“Paganel! Paganel! what’s the matter?” asked Glenarvan.

Paganel disengaged himself from the stirrups. “My friend, I am well. My horse is not!”

“What! Your horse?”

“Dead, like Mulrady’s, as if a thunderbolt had struck him!”

Glenarvan, John Mangles, and Wilson examined the animal, and found Paganel was right. His horse had been suddenly struck dead.

“This is strange,” said John.

“Very strange, indeed,” muttered the Major.

Glenarvan could not help being concerned by this new accident. They could not go back in this wilderness, and if an epidemic was going to seize their steeds, it would be very difficult to proceed.

Before the close of the day, it seemed as if the word “epidemic” was justified. A third horse, Wilson’s, fell dead, and what was, perhaps, more serious, two of the oxen as well. The means of traction and transport were now reduced to four oxen1 and four horses.

The situation became serious. The dismounted horsemen could, of course, continue on foot. Many squatters had already done so through these deserted regions. But if it became necessary to abandon the wagon, what would the ladies do? Could they cross the one hundred and twenty miles that still separated them and Twofold Bay?

John Mangles and Lord Glenarvan examined the surviving horses with great uneasiness, but there was not the slightest symptom of illness or even feebleness in them. The animals were in perfect health, and bravely bearing the exertions of the trip. This somewhat reassured Glenarvan, and made him hope that the malady would strike no more victims.

Ayrton agreed with him, but he confessed to have no understanding of what had caused these sudden deaths.

The night passed … beneath a vast mass of tree ferns

They went on again, with the pedestrians taking turns resting in the wagon. In the evening, after a march of only ten miles, the signal to halt was given, and they pitched the tent. The night passed without difficulty beneath a vast mass of tree ferns, between which enormous bats — properly called flying foxes — were flapping about.

The next day, January 13th, was good. There were no new calamities. The health of the expedition remained satisfactory; horses and oxen did their task cheerily. Lady Helena’s drawing room was very lively, thanks to the number of visitors. Mr. Olbinett busied himself in passing around refreshments, that thirty degrees2 of heat made necessary. They went through half a barrel of scotch ale. Barclay and Co. were declared to be the greatest men in Great Britain, even above Wellington, who could never have manufactured such good beer. This was their opinion, as Scots. Jacques Paganel drank deeply, and discoursed still more de omni re scibili.3

A day so well commenced seemed as if it could only end well; they had gone a good fifteen miles, and adroitly passed a fairly mountainous country with reddish soil. There was every reason to hope they might camp that night on the banks of the Snowy River, an important river which flows south through Victoria, into the Pacific. Soon the wheels of the wagon were making deep ruts on wide plains of blackish alluvium. It passed on between tufts of luxuriant grass and fresh fields of Gastrolobium. As evening came on, a white mist on the horizon marked the course of the Snowy. The strength of the team pulled them on a few more miles, and a forest of tall trees came in sight at a bend of the road, beyond a gentle slope. Ayrton led his overworked team through the great trunks, lost in shadows, and he was already past the edge of the wood, half a mile from the river, when the wagon suddenly sank up to the wheel hubs.

“Stop!” he called out to the horsemen following him.

“What is it?” asked Glenarvan.

“We’re bogged down,” said Ayrton.

He tried to stimulate the oxen to a fresh effort by voice and with the goad, but the animals were buried halfway up their legs, and could not stir.

Bright flashes of lightning … illuminated the horizon

“Let’s camp here,” said John Mangles.

“That’s the best thing to do,” said Ayrton. “Tomorrow, by daylight, we’ll see how to get it out.”

Glenarvan called for a halt.

Night came on rapidly after a brief twilight, but the heat wasn’t reduced by the end of day. Stifling vapours filled the air, and occasionally bright flashes of lightning, the reflections of a distant storm, illuminated the horizon. They prepared for the night. They did the best they could with the sunken wagon, and the tent was pitched beneath a dark dome of tall trees. If the rain held off, they had not much to complain about.

Ayrton succeeded, with some difficulty, in extricating the oxen from the mud. These courageous beasts had been engulfed up to the flanks. The quartermaster turned them out with the horses, and allowed no one but himself to see to their fodder. He had always executed this task well, and this evening Glenarvan noticed he redoubled his care, for which he took occasion to thank him. The preservation of the team was of supreme importance.

During this time, the travellers took part in a rather summary supper. Exhaustion and heat had destroyed appetites, and they wanted sleep more than food. Lady Helena and Miss Grant bade the company good night, and retired to their berths in the wagon. The men soon stretched themselves under the tent, or outside on the thick grass under the trees, which is no great hardship in this wholesome climate.

Gradually they all fell into a heavy sleep. A thick curtain of clouds over the sky deepened the darkness. There was not a breath of wind in the air. The silence of night was only interrupted by the hooting of the “morepork” which sang the minor third with a surprising accuracy, like the sad cuckoo of Europe.

About eleven o’clock, after a poor, heavy, un-refreshing sleep, the Major woke. His half-closed eyes were struck with a faint light running under the tall tress. It looked like a white sheet, shimmering like the waters of a lake. At first, MacNabbs thought that it was the first glimmers of a fire spreading over the ground.

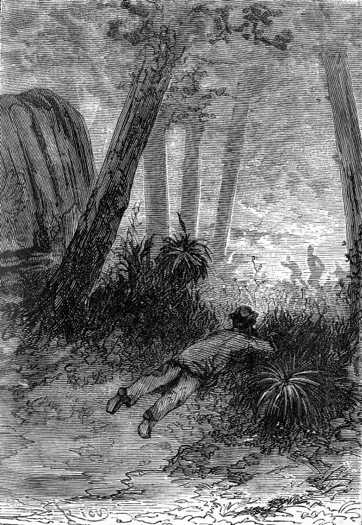

MacNabbs lay down on the ground

He got up, and went toward the wood. He was greatly surprised to discover a purely natural phenomenon! Under his eyes lay an immense bed of mushrooms, which emitted a phosphorescent light. The luminous spores of the cryptogams shone intensely in the darkness.4

The Major, who was not selfish, was about to waken Paganel so that he might see this phenomenon with his own eyes when an incident stopped him.

This phosphorescent glow illumined the wood for half a mile, and MacNabbs thought he saw a shadow pass across the edge of it. Were his eyes deceiving him? Was it some hallucination?

MacNabbs lay down on the ground, and, after a close scrutiny, he could distinctly see several men bending down and rising, in turn, as if they were looking on the ground for recent marks.

The Major resolved to find out what these fellows were about, and without the least hesitation or so much as arousing his companions, crept along, lying flat on the ground like a savage on the prairies, completely hidden among the long grass.

1. Verne has one ox die, reducing them to three, at this point, seeming having forgotten that they started out with six. I might have gone back and changed the initial number, but several of the Riou illustrations show six oxen as well. So I’m going to be killing off a couple more than Verne did — DAS

2. 86° Fahrenheit — DAS

3. Latin: “about every knowable thing” — DAS

4. This fact had already been mentioned by Drummond, who had noticed it in Australia in field mushrooms belonging to the family of the Omphalotus olearius.