A shot rang out

A shot rang out

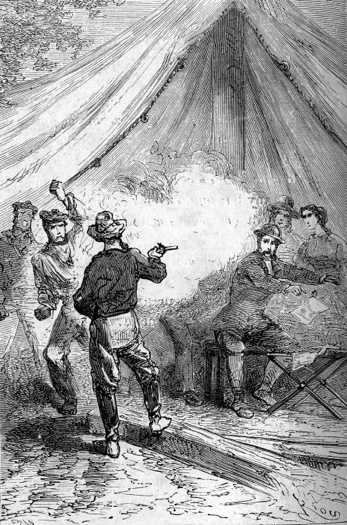

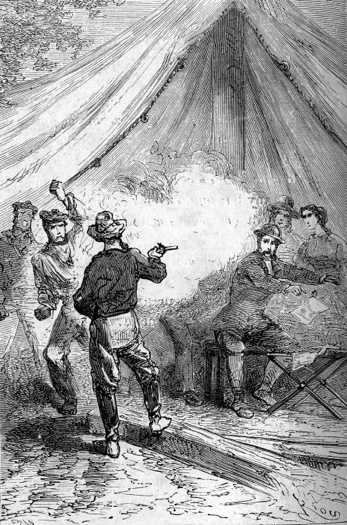

The revelation of Ben Joyce’s name struck like a thunderbolt. Ayrton lunged to his feet, a revolver in his hand. A shot rang out and Glenarvan fell, wounded. Gunshots resounded outside.

John Mangles and the sailors, after this first surprise, tried to throw themselves on Ben Joyce, but the audacious convict had already disappeared, and rejoined his gang scattered among the gum trees.

The tent was no shelter against bullets. They had to retreat. Glenarvan’s wound was slight, and he could stand.

“To the wagon! To the wagon!” cried John Mangles, dragging Lady Helena and Mary Grant along. They were soon safe behind the thick planks. John, the Major, Paganel, and the sailors seized their rifles and stood ready to repulse the convicts. Glenarvan and Robert went in with the ladies, while Olbinett rushed to join the defence.

It all took place in an instant, like a lighting flash. John Mangles watched the edge of the wood carefully. The gunshots had ceased as soon as Ben Joyce reached the trees. A deep silence had succeeded the noisy fusillade. A few wisps of white smoke were still curling through the branches of the gum trees. The tall tufts of Gastrolobium were motionless. All signs of attack had disappeared.

The Major and John Mangles made a reconnaissance to the tall trees. The area was abandoned. They found many footprints, and the smouldering remains of expended primers on the ground. The Major, a prudent man, extinguished these carefully, for a spark would be enough to kindle a firestorm in this forest of dry trees.

“The convicts have disappeared!” said John Mangles.

“Yes,” replied the Major, “and this disappearance disturbs me. I prefer seeing them face to face. Better to meet a tiger on the plain than a snake in the grass. Let’s beat the bushes around the wagon.”

The Major and John searched the surrounding countryside. From the edge of the wood to the banks of the Snowy, there was not a convict to be seen. Ben Joyce and his gang seemed to have flown away like a flock of marauding birds. It was too strange a disappearance to let the travellers feel safe. They decided to keep a sharp lookout. The wagon, a veritable moored fortress, was made the centre of the camp, with two men mounted guard who were relieved hour by hour.

The first care of Lady Helena and Mary was to dress Glenarvan’s wound. Lady Helena had rushed toward him in terror, as he fell down struck by Ben Joyce’s ball. Controlling her anguish, the courageous woman helped her husband into the wagon. His shoulder was bared, and the Major found, on examination, that the ball had only gone into the flesh, and there was no internal lesion. Neither bone nor muscle appeared to be injured. The wound bled profusely, but Glenarvan, wagging his forearm, reassured his friends that the injury was not serious. As soon as his shoulder was dressed, he would not allow any more fuss to be made about him. He wanted an explanation of what had just happened.

Everyone except Mulrady and Wilson, who were on guard, were crowded into the wagon, and the Major was invited to speak.

He started by telling Lady Helena the things that had been withheld from her: about the escape of the convicts from Perth, and their appearance in Victoria and their complicity in the railway catastrophe. He handed her the Australian and New Zealand Gazette he had bought in Seymour, and added that a reward had been offered by the police for the apprehension of Ben Joyce, a formidable bandit, whose crimes during the last eighteen months had made him a notorious celebrity.

But how had MacNabbs learned that Ayrton was Ben Joyce? This was a mystery that everyone wanted an explanation for, and the Major soon supplied it.

Ever since their first meeting, MacNabbs had felt an instinctive wariness of the quartermaster. Two or three insignificant facts, a glance exchanged between him and the blacksmith at the Wimmera River, his hesitation at entering towns and villages, his persistence about getting the Duncan summoned to the coast, the strange death of the animals entrusted to his care, and, lastly, a lack of frankness in all his behaviour. Little by little, all these details had combined to awaken the Major’s suspicions.

However, he could not have made any direct accusation until the events of the previous night.

MacNabbs, slipping between the tall shrubs, came near the suspicious shadows he had noticed about half a mile away from the camp. The phosphorescent mushrooms threw pale gleams in the darkness.

Three men were examining fresh footprints on the ground, and MacNabbs recognized one of them as the blacksmith from Black Point. “It’s them!” said one of the men. “Yes,” said another, “there’s the clover mark of the horseshoe.” — “It has been like that since the Wimmera.” — “All the other horses are dead.” — “The poison is all around us.” — “There is enough here to kill a regiment of cavalry.” — “A useful plant, this Gastrolobium!”

The men fell silent and started to move off, but the Major needed to know more, so he followed them. Soon the conversation began again. “He is a clever fellow, this Ben Joyce,” said the blacksmith. “A capital quartermaster, with his invention of a shipwreck.” — “If his project succeeds, it will be a stroke of fortune.” — “He’s the very devil, this Ayrton.” — “Call him Ben Joyce, for he has earned his name!” The scoundrels left the forest, and the Major had learned all he needed, so he returned to the camp, convinced that, despite Paganel’s beliefs, Australia did not reform criminals.

When the Major was done recounting the story, his companions sat silently, thinking it over.

“Then Ayrton has dragged us here,” said Glenarvan, pale with anger, “to rob and murder us.”

“Yes,” said the Major.

“And ever since the Wimmera his gang has been following in our footsteps, and watching for a favourable opportunity.”

“Yes.”

“Then the wretch was never one of the sailors on the Britannia. Did he steal the name of Ayrton and the shipping papers?”

They all looked at MacNabbs, for he must have asked himself that question already.

“Here,” he answered in his still calm voice, “are the facts that can be drawn from this obscure situation. In my opinion the man is actually named Ayrton. Ben Joyce is his nom de guerre. It is undeniable that he knew Harry Grant, and also that he was quartermaster on the Britannia. These facts were already proved by the precise details given us by Ayrton, and are corroborated by the conversation between the convicts, which I repeated to you. Let us not be diverted into idle speculation, but take it for granted that Ben Joyce is Ayrton, and that Ayrton is Ben Joyce. That is to say, one of the crew of the Britannia has become the leader of a convict gang.”

MacNabbs’ explanation was accepted without discussion.

“Now,” said Glenarvan, “will you tell us how and why Harry Grant’s quartermaster is in Australia?”

“How, I don’t know,” said MacNabbs. “And the police say that they don’t know, either. Why? It is impossible to say. That is a mystery which the future may explain.”

“The police are not even aware that Ayrton is Ben Joyce,” said John Mangles.

“You are right, John,” said the Major, “and this information would throw light on their search.”

“Then I suppose,” said Lady Helena, “the despicable man had some criminal intent for getting work on Paddy O’Moore’s farm?”

“No doubt,” said MacNabbs. “He was planning some evil design against the Irishman, when a better opportunity presented itself. Chance led us to him. He heard Glenarvan’s story, the story of the shipwreck, and the audacious fellow quickly decided to take advantage of it. The expedition was decided on. At the Wimmera he found the means to contact one of his gang, the blacksmith from Black Point, and left recognizable traces of our passage. The gang followed us. A poisonous plant enabled him to kill our oxen and horses little by little. When the time came, he bogged us down in the marshes of the Snowy, and gave us into the hands of his gang.”

There was nothing more to say about Ben Joyce. His past had been reconstructed by the Major, and the wretch appeared as he was, a daring and formidable criminal. His intentions, clearly demonstrated, required extreme vigilance from Glenarvan. Fortunately, there was less to fear from the unmasked bandit than from the traitor.

But from this clarified situation emerged a serious consequence. No one had thought of it yet, except Mary Grant. Putting aside all the discussion of the past, she thought of the future. John Mangles was the first to notice her pale, despairing face; he understood what was passing through her mind at a glance.

“Miss Mary! Miss Mary! You’re crying!”

“Why are you crying, my child?” asked Lady Helena.

“My father, Madame. My father!” said the poor girl.

She could not continue, but the truth flashed in every mind. They all knew the cause of Mary’s grief, and why tears fell from her eyes and why her father’s name rose from her heart to her lips.

The discovery of Ayrton’s treachery had destroyed all hope. The convict had invented the shipwreck to entrap Glenarvan. In the conversation overheard by MacNabbs, the convicts had plainly said that the Britannia had never been wrecked on the rocks in Twofold Bay. Harry Grant had never set foot on the Australian continent!

For the second time an erroneous interpretation of the document had thrown the searchers for the Britannia on a wrong track.

A gloomy silence fell over the whole party at the sight of the children’s sorrow in the face of this situation. No one could find a hopeful word to say. Robert was crying in his sister’s arms.

“That damnable document!” Paganel muttered pitifully to himself. “It can boast of having scrambled the wits of a dozen brave people!”

And the worthy geographer was in such a rage with himself, that he struck his forehead as if he would smash it.

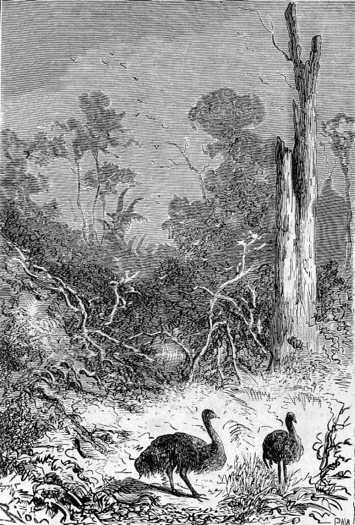

A couple of emus … passed between the shrubs

Glenarvan went out to Mulrady and Wilson, who were keeping watch. Profound silence reigned over the plain between the woods and the river. The big, motionless clouds were pressing down on the roof of the sky. The atmosphere was numbed with a deep torpor, the least noise was transmitted clearly, and nothing was heard. Ben Joyce and his band must must have retreated to a considerable distance. It was evident from the flocks of birds frolicking on the lower branches of the trees, the kangaroos feeding quietly on the young shoots, and a couple of emus whose confident heads passed between the great clumps of bushes, that those peaceful solitudes were untroubled by the presence of human beings.

“Have you either seen or heard anything in the last hour?” Glenarvan asked the two sailors.

“Nothing whatever, Your Honour,” said Wilson. “The convicts must be several miles from here.”

“They must not have been strong enough to attack us,” said Mulrady. “This Ben Joyce must have wanted to recruit more bandits of his kind among the bushrangers roaming about the foot of the Alps.”

“Possibly, Mulrady,” said Glenarvan. “These rascals are cowards. They know we are well armed. Perhaps they are waiting for nightfall to commence their attack. We must redouble our watch at sunset. Oh, if we could only get out of this bog, and down to the coast; but this swollen river bars our way. I would pay its weight in gold for a raft which would carry us over to the other side.”

“Why is Your Honour not giving us the orders to build a raft? We have plenty of wood.”

“No, Wilson,” said Glenarvan. “This Snowy is not a river, it is an impassable torrent.”

John Mangles, the Major, and Paganel were just returning from looking at the Snowy. They reported that the waters, swollen from the rain, were still a foot above their normal level. It formed a torrent like the rapids of America. It was impossible to venture over the foaming current of that rushing flood, broken into a thousand eddies and hollows and gulfs.

John Mangles declared the passage impossible.

“But we must not stay here, without attempting anything,” he said. “What we were going to do before Ayrton’s treachery is now even more necessary.”

“What do you mean, John?” asked Glenarvan.

“I mean that we must get relief, and that since we cannot go to Twofold Bay, we must go to Melbourne. We still have one horse. Give it to me, My Lord, and I will go to Melbourne.”

“That will be a dangerous undertaking, John,” said Glenarvan. “Ben Joyce and his accomplices will be guarding the roads, not to mention the perils of a journey of two hundred miles over an unknown country.”

“I know that, My Lord, but I also know that things can’t stay long as they are. Ayrton was only asking for eight days to bring back the Duncan’s men. I want to be back on the banks of the Snowy in six. Well, what is Your Honour’s order?”

“Before Glenarvan decides,” said Paganel, “I must make an observation. That someone must go to Melbourne is evident, but it cannot be John Mangles who exposes himself to the risk. He is the captain of the Duncan, and must be careful of his life. I will go instead.”

“Well spoken,” said the Major. “But why should it be you, Paganel?”

“Aren’t we here?” said Mulrady and Wilson.

“And do you think,” said MacNabbs, “that I’m afraid of a ride of two hundred miles on horseback?”

“My friends,” said Glenarvan, “if any of us should go to Melbourne, let fate designate him. Paganel, write our names—”

“Not yours, My Lord,” said John Mangles.

“And why not?”

“Separate you from Lady Helena, when your wound is not even closed!”

“Glenarvan,” said Paganel, “you cannot leave the expedition.”

“Your place is here, Edward,” said the Major. “You must not leave.”

“There are dangers to run,” said Glenarvan, “and I will not leave them to others. Write the names, Paganel, and put mine among them, and I hope the lot may fall on me.”

They bowed before his will. Glenarvan’s name was added to the others. The draw was made, and the fate fell upon Mulrady. The brave sailor crowed with satisfaction.

“My Lord, I am ready to start,” he said.

Glenarvan squeezed Mulrady’s hand. He returned to the wagon, leaving John Mangles and the Major on watch.

Lady Helena was informed of the decision to send a message to Melbourne, that they had drawn lots who should go, and Mulrady had been chosen. She said a few kind words to the valiant sailor, which went straight to his heart. Fate could hardly have chosen a better man, for he was not only brave and intelligent, but strong and tireless.

Mulrady’s departure was set for eight o’clock, after the short evening twilight. Wilson took charge of preparing the horse. He had the idea of changing the horse’s revealing left shoe, for one off a horse that had died in the night. This would prevent the convicts from tracking Mulrady, or following him, as they were not mounted.

While Wilson was arranging this, Glenarvan prepared the letter for Tom Austin, but his injured arm troubled him, and he asked Paganel to write it for him. The scientist, was so absorbed in some fixed idea that he seemed hardly aware of what was happening around him. It must be said, in all this succession of unfortunate adventures, that Paganel thought only of the falsely interpreted document. He turned the words over in his mind, attempting to extract a new meaning from them, and remained immersed in the abysses of interpretation.

So, he did not hear Glenarvan’s request, and he was forced to repeat it.

“Ah, very well,” said Paganel. “I’m ready.”

While talking, Paganel mechanically prepared his notebook. He tore a blank page off and, pencil in hand, he prepared to write. Glenarvan began to dictate his instructions.

“Order Tom Austin to get to sea without delay, and bring the Duncan to…”

Paganel was just finishing the last word, when his eye chanced to fall on the Australian and New Zealand Gazette lying on the ground. The folded newspaper was showing only part of its title. Paganel’s pencil stopped, and he seemed to completely forget Glenarvan, his letter, his dictation…

“Come, Paganel!”

“Ah!” started the geographer.

“What is the matter?” asked the Major

“Nothing, nothing,” said Paganel. Then he muttered to himself, “E-land, e-land, e-land!”

He had risen. He had seized the newspaper. He shook it, in his efforts to keep back the words that tried to escape from his lips. Lady Helena, Mary, Robert, and Glenarvan looked at him without understanding anything about this inexplicable agitation.

Paganel looked like a man suddenly struck by madness. But this state of nervous excitement did not last. He calmed himself, little by little. The gleam of joy that shone in his eyes died away. He sat down again, and said quietly “When you please, My Lord, I am at your service.”

Glenarvan resumed his dictation of his letter, which was definitely worded as follows:

Order to Tom Austin to sail without delay and to bring the Duncan by 37° of latitude to the eastern coast of Australia …

“Of Australia?” said Paganel. “Ah yes! Of Australia.”

Then he finished the letter, and presented it for signature. Glenarvan, still troubled by his wound, signed the order without reading it. Paganel closed and sealed the letter, and with a hand still trembling from emotion addressed the envelope.

Tom Austin,

Second aboard the yacht Duncan,

Melbourne

Then he left the wagon, gesticulating and repeating the incomprehensible words: “E-land, e-land, Zealand!”