The gusts of wind redoubled their violence

The rest of the day passed without further incident. All the preparations for Mulrady’s departure were completed, and the brave sailor was happy to give His Honour this mark of his devotion.

Paganel had regained his composure and his accustomed manner. His gaze still showed his pre-occupation, but he seemed determined to keep it secret. No doubt he had strong reasons for doing so, for the Major heard him muttering “No, no! They would not believe me. And, besides, what’s the point? It’s too late!” like a man struggling with himself.

Having taken this resolution, he busied himself with giving Mulrady the necessary directions for getting to Melbourne, and showed him his way on the map. All the paths from their location on the Snowy led to the Lucknow road. This road, after running directly south to the coast, took a sudden bend toward Melbourne. This was the route that must be followed, for it would not do to attempt a short cut across almost unknown country. So nothing could be simpler. Mulrady could not lose his way.

As to dangers, there were none after he had gone a few miles beyond the camp, where Ben Joyce and his gang might be waiting in ambush. Once past them, Mulrady was certain of being able to outdistance the convicts, and complete his mission.

At six o’clock they all dined together. The rain was falling in torrents. The tent was not protection enough, and the whole party had to take refuge in the wagon. It was, moreover, a safe retreat. The clay kept it firmly embedded in the ground, like a fortress resting on firm foundations. The arsenal was composed of seven rifles and seven revolvers, and they could stand a pretty long siege, for they had plenty of ammunition and provisions. But before six days were over, the Duncan would anchor in Twofold Bay, and a few days later her crew would reach the other shore of the Snowy; and should the passage still remain impracticable, the convicts at any rate would be forced to retire before the superior force. But it all depended on Mulrady’s success in his perilous enterprise.

At eight o’clock the night became very dark. It was time to start. The horse prepared for Mulrady was brought out. His hooves were wrapped with cloths as a precaution, to muffle the sound of them on the ground. The animal seemed tired, and yet the safety of all depended on his strength and sure footedness. The Major advised Mulrady to let him go gently as soon as he had got past the convicts. Better a half day delay than not to arrive at all.

John Mangles gave his sailor a revolver he had loaded with great care. This is a formidable weapon in the hand of a man who does not hesitate to use it, for six shots fired in a few seconds would easily clear an obstruction of criminals from a path.

Mulrady seated himself in the saddle, ready to start.

“Here is the letter you are to give to Tom Austin,” said Glenarvan. “Don’t let him lose an hour. He is to sail for Twofold Bay at once, and if he does not find us there, if we have not managed to cross the Snowy, let him come on to us without delay, Now go, my brave sailor, and God be with you.”

Glenarvan, Lady Helena, Mary Grant and the rest all shook hands with Mulrady. The departure on such a dark, raining night, on a road strewn with danger, through the unknown immensities of a wilderness, would have daunted a heart less firm than that of the sailor.

“Farewell, My Lord,” he said in a calm voice, and he soon disappeared by a path that ran along the edge of the woods.

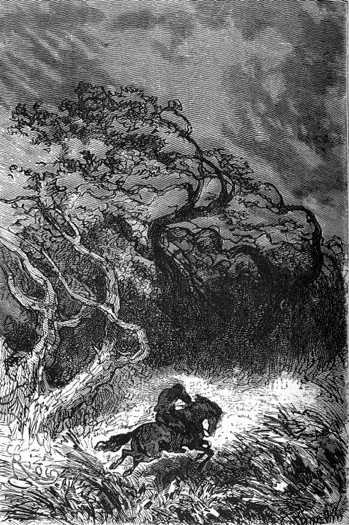

The gusts of wind redoubled their violence

The gusts of wind redoubled their violence. The high branches of the eucalyptus rattled dully in the dark. They could hear the sound of broken branches striking the sodden soil. More than one giant tree, with no living sap, but still standing until then, fell during this tempestuous squall. The wind howled through the crackling wood, and mingled its ominous moans with the roaring of the Snowy. The heavy clouds, driving along toward the east, hung on the ground like rags of steam. A gloomy darkness intensified the horrors of the night.

The rest of the party, after Mulrady’s departure, went back into the wagon. Lady Helena, Mary Grant, Glenarvan, and Paganel occupied the first compartment, which had been hermetically closed. The second was occupied by Olbinett, Wilson, and Robert. The Major and John Mangles were on watch outside. This precaution was necessary, for an attack by the convicts would be easy enough, and therefore probable enough.

The two faithful guardians kept close watch, bearing philosophically the rain and wind that beat on their faces. They tried to see through the darkness, so perfect for ambushes, for nothing could be heard in the midst of the sounds of the storm: the howling of the wind, the rattling branches, falling trees, and roaring of the unchained waters.

At times the wind would cease for a few moments, as if to take breath. Nothing was audible but the moan of the Snowy as it flowed between the motionless reeds and the dark curtain of gum trees. The silence seemed deeper in these momentary lulls, and the Major and John Mangles listened attentively.

During one of these calms a sharp whistle reached them.

John Mangles quickly went up to the Major.

“You heard that?” he asked.

“Yes,” said MacNabbs. “Is it man or beast?”

“A man,” replied John Mangles.

They both listened. The mysterious whistle was repeated, and answered by a kind of detonation, but almost indistinguishable, for the storm was raging with renewed violence. MacNabbs and John Mangles could not hear themselves speak. They went under the shelter of the wagon.

The leather curtains were raised, and Glenarvan joined his two companions. He too had heard that sinister whistle, and the report which echoed under the tarpaulin.

“Which way was it?” he asked.

“There,” said John, pointing to the dark track in the direction taken by Mulrady.

“How far?”

“The wind brought it,” said John Mangles. “It must be at least three miles.”

“Come on!” said Glenarvan, putting his gun on his shoulder.

“No!” said the Major. “It’s a decoy to get us away from the wagon.”

“But if Mulrady has fallen to the blows of these miscreants!” said Glenarvan, seizing MacNabbs by the hand.

“We shall know by tomorrow,” said the Major, coolly, determined to prevent Glenarvan from taking a rash and futile action.

“You cannot leave the camp, My Lord,”said John. “I will go alone.”

“You will do nothing of the kind!” said MacNabbs, firmly. “Do you want us to be killed in detail, to diminish our strength, to put ourselves at the mercy of these criminals? If Mulrady has fallen victim to them, it is a misfortune that must not be repeated. Mulrady was sent, chosen by chance. If the lot had fallen to me, I would have gone as he did. I would not have asked for, nor expected, any help.”

In restraining Glenarvan and John Mangles, the Major was right in every respect. To try to reach the sailor, to run into the darkness of night among the convicts in their leafy ambush was foolish, and more than that, it was useless. Glenarvan’s party was not so numerous that it could afford to sacrifice another member of it.

Still, Glenarvan seemed as if he would not yield to reason. He kept his rifle gripped firmly in his hands. He wandered around the wagon. He listened to the faintest sound. He tried to pierce the sinister darkness. The thought that one of his party was, perhaps, mortally wounded, abandoned without help, calling in vain to those for whom he had devoted himself, was a torture to him. MacNabbs was not sure that he could succeed in holding him back, or if Glenarvan, carried away by his feelings, would not run into the arms of Ben Joyce.

“Edward, calm down,” he said. “Listen to a friend. Think of Lady Helena, of Mary Grant, of all who are left. And, besides, where would you go? Where would you find Mulrady? He must have been attacked two miles off. In what direction? Which path would you follow?”

At that moment, as if to answer the Major, a cry of distress was heard.

“Listen!” said Glenarvan.

This cry came from the same direction as the report, but less than a quarter of a mile off. Glenarvan, pushing past MacNabbs, was already on the path when he heard the call again, originating hundred paces away from the wagon.

“Help! Help!”

It was a plaintive and desperate voice. John Mangles and the Major sprang toward the spot.

A few seconds later they saw a human form dragging himself on the ground along the tree line, and uttering grim groans.

It was Mulrady, wounded, dying, and when his companions lifted him, they felt their hands bathed in blood.

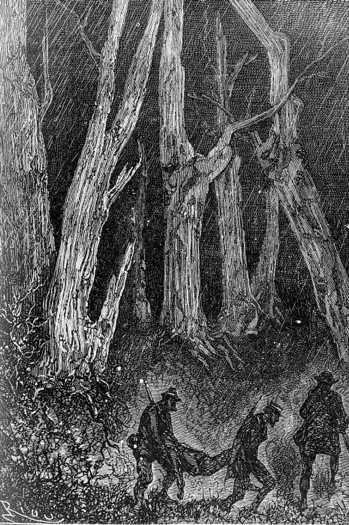

They carried Mulrady back to the wagon

The rain came down with redoubled violence, and the wind raged among the branches of the dead trees. In the pelting storm, Glenarvan, the Major, and John Mangles carried Mulrady back to the wagon.

Everyone got up when they arrived. Paganel, Robert, Wilson, and Olbinett left the wagon, and Lady Helena gave up her berth to poor Mulrady. The Major removed the sailor’s jacket, which was dripping with blood and rain. He soon found the wound; the unfortunate man had been stabbed in the right side.

MacNabbs skilfully dressed the wound. He could not tell whether the weapon had reached any vital organ. An intermittent jet of scarlet blood flowed from it. The patient’s paleness and weakness showed that he was seriously injured. The Major washed the wound first with fresh water and then closed the opening. He covered the wound with a thick pad of tinder, and then folds of linen held in place with a bandage. He managed to stop the bleeding. Mulrady was laid on his side, with his head and chest raised, and Lady Helena gave him a few sips of water.

After about a quarter of an hour, the wounded man, who until then had lain motionless, stirred. His eyes opened; his lips muttered incoherent words; the Major, bending close to him, heard him repeating “My Lord … the letter … Ben Joyce.”

The Major repeated these words, and looked at his companions. What did Mulrady mean? Ben Joyce had attacked the sailor, but why? Wasn’t it just to stop him, to prevent him reaching the Duncan? The letter…

Glenarvan searched Mulrady’s pockets. The letter addressed to Tom Austin was gone!

The night passed in anxiety and worry. It was feared every moment that Mulrady would die. A burning fever consumed him. Lady Helena and Mary Grant, two sisters of charity, never left him. Never was a patient so well cared for, nor by such compassionate hands.

Dawn approached. The rain had stopped. Large clouds still rolled across the sky. The ground was strewn with broken branches. The clay, soaked by the torrents of rain, had softened again. The approaches to the wagon became difficult, but it could not sink any deeper.

At daybreak, John Mangles, Paganel, and Glenarvan went to reconnoitre around the camp. They went up the path which was still stained with blood. They saw no vestige of Ben Joyce, or his band. They went as far as to where the attack had taken place. Here, two corpses lay on the ground, hit by Mulrady’s bullets. One was the Black Point blacksmith. His face, decomposing in death, was a horror.

Glenarvan did not go farther. Prudence forbade him from wandering far from the camp. He returned to the wagon, deeply absorbed by the gravity of the situation.

“We must not think of sending another messenger to Melbourne,” he said.

“But we must,” said John Mangles. “I will try to go where my sailor could not succeed.”

“No, John! You do not even have a horse to carry you those two hundred miles!”

This was true, for Mulrady’s horse, the only one that remained, had not returned. Had he fallen during the attack on his rider, or was he straying in the bush, or had the convicts seized him?

“Whatever happens, we will not separate,” said Glenarvan. “Let’s wait a week, a fortnight if need be, for the Snowy to return to its normal level. We can then reach Twofold Bay by short stages, and from there we can send orders to the Duncan by a safer route, along the coast.”

“That seems the only option,” said Paganel.

“So, my friends, no more separation,” said Glenarvan. “It is too great a risk for one man to venture alone into this bandit infested wilderness. And now, may God save our poor sailor, and protect the rest of us!”

Glenarvan was right on both points: first in prohibiting any solo attempts, and second, in deciding to wait until the crossing of the Snowy River was possible. He was scarcely thirty miles from Delegate, the first frontier village of New South Wales, where he would find transportation to Twofold Bay, and from there he could telegraph to Melbourne his orders to the Duncan.

These measures were wise, but they were taken late. If Glenarvan had not sent Mulrady on the road to Lucknow what misfortunes might have been averted? To say nothing of the assassination of the sailor!

When Glenarvan returned to the camp, he found his companions in better spirits. They seemed more hopeful than before.

“He’s getting better! He’s getting better!” cried Robert, running out to meet Lord Glenarvan.

“Mulrady?”

“Yes, Edward,” said Lady Helena. “His fever has broken. The Major is more confident. Our sailor will live.”

“Where is MacNabbs?” asked Glenarvan.

“With him. Mulrady wanted to speak to him. Don’t disturb them.”

The wounded man had awakened about an hour ago, and his fever had abated. The first thing Mulrady did on recovering his wits and speech, was to ask for Lord Glenarvan, or failing him, the Major. MacNabbs seeing him so weak, would have forbidden any conversation, but Mulrady insisted with such energy that the Major had to give in.

The conversation had already lasted some minutes when Glenarvan returned. The only thing to do now was wait for MacNabbs’ report.

Presently, the leather curtains of the wagon opened, and the Major appeared. He rejoined his friends at the foot of a gum tree where the tent was erected. His face, usually so stolid, showed that something disturbed him. When his eyes fell on Lady Helena and the young girl, his glance was full of sorrow.

Glenarvan questioned him, and this is essentially what the major had just learned.

Five men threw themselves at the horse’s head

When he left the camp Mulrady followed one of the paths indicated by Paganel. He made as good speed as the darkness of the night would allow. He reckoned that he had gone about two miles when several men — five he thought — threw themselves at his horse’s head. The animal reared; Mulrady seized his revolver and fired. He thought he saw two of his assailants fall. He recognized Ben Joyce in the muzzle flash, but that was all. He hadn’t had time to fire all the chambers. He felt a violent blow to his right side and was thrown to the ground.

However, he had not lost consciousness. The assailants thought he was dead. He felt them search his pockets, and then he heard them speak. “I have the letter,” said one of the convicts. “Give it to me,” said Ben Joyce, “and now the Duncan is ours.”

At this point in MacNabbs’ story, Glenarvan could not suppress a cry.

“Now you fellows,” said Ben Joyce, “catch the horse. In two days I shall be on board the Duncan, and in six I shall reach Twofold Bay. That is the rendezvous. The Lord and his party will be still mired in the marshes of the Snowy. Cross the river at Kemple Pier bridge, proceed to the coast, and wait for me. I will find a way to get you on board. Once at sea in a ship like the Duncan, we shall be masters of the Indian Ocean.” “Hurrah for Ben Joyce!” cried the convicts. Mulrady’s horse was brought, and Ben Joyce galloped away on the Lucknow road, while the band took the road south-east to the Snowy River. Mulrady, though severely wounded, had the strength to drag himself to within three hundred paces from the camp where they found him almost dead.

“And that,” said MacNabbs, “is Mulrady’s story. And now you can understand why the brave fellow was so determined to speak.”

This revelation terrified Glenarvan and the rest of the party.

“Pirates! Pirates!” cried Glenarvan. “My crew massacred! My Duncan in the hands of these bandits!”

“Yes, for Ben Joyce will surprise the ship,” said the Major, “and then…”

“Well, we must get to the coast before them,” said Paganel.

“But how are we to cross the Snowy?” said Wilson.

“As they will,” replied Glenarvan. “They are to cross at Kemple Pier Bridge, and so will we.”

“But what about Mulrady?” asked Lady Helena. “What will become of him?”

“We will carry him; we will take turns. Can I leave my crew to the mercy of Ben Joyce and his gang?”

It might be possible to cross the Snowy at Kemple Pier bridge, but dangerous. The convicts might entrench themselves at that point, and defend it. They were at least thirty against seven! But there are times when you don’t count the odds, when you have no choice but to go on.

“My Lord,” said John Mangles, “before risking our last chance, before venturing to this bridge, we ought to reconnoitre, and I will undertake it.”

“I will go with you, John,” said Paganel. This proposal was agreed to, and John Mangles and Paganel prepared to leave at once. They had to go down the Snowy, follow its banks until they reached the place indicated by Ben Joyce, and especially avoid the sight of any convicts, who might be beating the banks.

So, well provisioned and armed, the two brave comrades set off and soon disappeared, sneaking through the tall reeds by the river.

The rest anxiously waited all day for their return. Evening came, and the scouts had not come back. They began to be seriously worried.

Finally, around eleven o’clock, Wilson signalled their return. Paganel and John Mangles were exhausted with the exertions of a ten mile walk.

Glenarvan sprang to meet them. “The bridge! Did you find it?”

“Yes, a creeper bridge,” said John Mangles. “The convicts passed over it, but…”

“But what?” asked Glenarvan, sensing some new misfortune.

“They burned it after they passed!” said Paganel.