The raft had reached the middle of the river

It was not a time for despair, but action. The bridge at Kemple Pier was destroyed, but the Snowy had to be crossed, and they must reach Twofold Bay before Ben Joyce and his gang, whatever the cost. Instead of wasting time in empty words, the next day, January 16th, John Mangles and Glenarvan went down to examine the river, in order to plan the crossing.

The tumultuous waters, swollen by the rains, had not gone down. They swirled with indescribable fury. It would be suicide to confront them. Glenarvan stood motionless, gazing with folded arms and downcast face.

“Do you want me to swim to the other shore?” asked John Mangles.

“No, John!” said Glenarvan, holding back the bold young man. “Wait!”

They both returned to the camp. The day passed in the most intense anxiety. Ten times Lord Glenarvan went to look at the river, trying to invent some bold way to cross it, but in vain. Had a torrent of lava rushed between the shores, it could not have been more impassable.

During these long wasted hours, Lady Helena, with advice from the Major, was nursing Mulrady with the utmost skill. The sailor felt his strength slowly returning. MacNabbs ventured to affirm that no vital organ was injured. The loss of blood was enough to account for the patient’s weakness. With the wound closed and the hemorrhage stopped, time and rest would be all that was needed to complete his cure. Lady Helena had insisted on giving up the first compartment of the wagon to him. Mulrady felt ashamed; his greatest concern was the delay that his condition might cause Glenarvan, and he made him promise that they would leave him in the camp under Wilson’s care should the passage of the river become possible.

Unfortunately, no passage was practicable, either that day or the next, January 17th. To see himself so blocked despaired Glenarvan. Lady Helena and the Major vainly tried to calm him, and urged him to be patient. Patient, when perhaps at that very moment Ben Joyce was boarding the yacht! When the Duncan, might be casting off her moorings, raising steam to reach the fatal coast, and each hour was bringing her nearer!

John Mangles felt all that Glenarvan was suffering in his own heart. He was determined to overcome the obstacle at any price, and constructed an Australian style canoe with large sheets of gum tree bark. These sheets were held together in a frame of wooden strips, and formed a very fragile boat.

The captain and Wilson tried this frail boat during the day of the 18th. All that skill, strength, tact, and courage could do, they did. But they were scarcely in the current before they capsized, and nearly paid with their lives for the dangerous experiment. The boat disappeared, dragged down by an eddy. John Mangles and Wilson had not gone five fathoms, and the river was fifty across, swollen by the heavy rains and melted snows.

The 19th and 20th of January passed in the same fashion. The Major and Glenarvan went five miles up the river without finding a ford. Everywhere they found the same roaring, rushing, impetuous torrent. The whole southern slope of the Australian Alps poured its liquid masses into this single bed.

It was necessary to give up any hope of saving the Duncan. Five days had elapsed since the departure of Ben Joyce. The yacht must at this moment be at the coast, and in the hands of the convicts!

It was impossible that this state of affairs could last. The very violence of the flood meant that it would soon be exhausted. On the morning of the 21st, Paganel went to the river, and found that the water was lower. He reported his observation to Glenarvan.

“What does it matter now?” said Glenarvan. “It is too late!”

“That’s no reason to prolonging our stay here,” said the Major.

“Indeed,” said John Mangles. “Perhaps tomorrow the river may be crossable.”

“And will that save my poor crew?” cried Glenarvan.

“Your Honour will listen to me,” said John Mangles. “I know Tom Austin. He would execute your orders, and set out as soon as departure was possible. But who knows whether the Duncan was ready, and her damage repaired when Ben Joyce arrived in Melbourne? And suppose the yacht could not go to sea. Suppose there was a delay of a day, or two days.”

“You are right, John!” said Glenarvan. “We must get to Twofold Bay. We are only thirty miles from Delegate.”

“Yes,” said Paganel, “and we will find some rapid means of transportation in that town. Who knows if we will not arrive in time to prevent a calamity?”

“Let’s get to it!” said Glenarvan.

John Mangles and Wilson immediately set to work to construct a large raft. Experience had shown that pieces of bark could not resist the violence of the torrent. John cut down some gum trees, and made a rough but solid raft with their trunks. It was a long task, and the day passed without it being finished. It was not completed until the next morning.

By this time the waters of the Snowy had significantly lowered. The torrent had once more become a river, though still a very rapid one. John hoped to be able to scull, and row, the raft to the opposite bank.

At half-past twelve, they packed two days of provisions into whatever they could carry. The remainder was abandoned with the wagon and the tent. Mulrady’s convalescence was progressing well enough that he could be moved.

At one o’clock, they all took their places on the raft still moored to the shore. John Mangles positioned Wilson on the starboard side with a roughly fashioned oar to steady the raft against the current, and reduce its drift. He stood at the back, with a large scull, to propel them along. Lady Helena and Mary Grant occupied the center of the raft near Mulrady. Glenarvan, the Major, Paganel, and Robert surrounded them, ready to help, if needed.

“Are we ready, Wilson?” John Mangles asked his sailor.

“Yes, Captain,” said Wilson, seizing his oar with a sturdy hand.

“Look out, and support us against the current.”

John Mangles untied the raft, and with a push he threw it into the waters of the Snowy. Everything went well for fifteen fathoms. Wilson’s oar kept them from drifting too far downstream. But soon the raft was caught in an eddy, and spun around more rapidly than their rowing or sculling could control. despite their best efforts, Wilson and John Mangles soon found themselves turned completely around, which made the action of the oars ineffective.

There was no help for it. They could do nothing to stop the gyrations of the raft. It spun around with dizzying rapidity, and drifted out of its course. John Mangles stood with pale face and set teeth, gazing at the whirling current.

The raft had reached the middle of the river

The raft had reached the middle of the river, about half a mile downstream from their starting point. Here, the current was extremely strong, and this broke the whirling eddies, and gave the raft some stability.

John and Wilson seized their oars again, and managed to push the raft diagonally across the current. This brought them nearer the left shore. They were only ten fathoms from it, when Wilson’s oar broke, and the raft, no longer supported against the current, was dragged downstream. John tried to resist at the risk of breaking his scull too, and Wilson, with bleeding hands, joined his efforts.

At last they succeeded and the raft, after a crossing that had taken more than half an hour, struck against the steep bank of the opposite shore. The shock was so violent that the cords holding the logs together broke, and the raft came apart. The travellers barely had time to catch hold of the brush overhanging the steep bank. They dragged Mulrady and the two dripping ladies to shore. Everyone was safe, but most of their provisions and weapons, except for the Major’s rifle, drifted away with the remains of the raft.

The river was crossed. The little company found themselves almost without resources, thirty miles from Delegate, in the midst of the unknown wilds of the Victoria frontier. Neither settlers nor squatters were to be met with, here. It was entirely uninhabited, unless by ferocious, bushranger bandits.

They resolved to set off at once, Mulrady saw that he would be a burden to them, and he asked to stay, alone, until assistance could be sent from Delegate.

Glenarvan refused. It would take at least three days to reach Delegate, and five days to reach the coast. He couldn’t hope to get there before January 26th. If the Duncan had left Melbourne on the 16th what difference would a few days’ delay make?

“No, my friend,” he said. “I will not leave anyone behind. We will make a litter and take turns carrying you.”

The litter was made of boughs of eucalyptus covered with branches. Willingly or not, Mulrady was obliged to take his place on it. Glenarvan would be the first to carry his sailor. He took hold of the stretcher at one end and Wilson took the other, and they set off.

What a sad spectacle. It ended so badly, this expedition which had started so well. They were no longer looking for Harry Grant. This continent, where he was not, and never had been, threatened to prove fatal to those who sought him. And when his daring compatriots reached the Australian coast, they wouldn’t even find the Duncan waiting to take them home again.

The first day passed silently and painfully. Every ten minutes the litter changed bearers. All the sailor’s comrades took their share in this task without complaining of fatigue, which was increased by a great deal of heat.

In the evening after a journey of only five miles, they camped under thicket of gum trees. The small store of provisions saved from the raft composed the evening meal. All they had to depend upon now was the Major’s rifle.

It was a dark, rainy night, and morning seemed as if it would never dawn. They set off again, but the Major could not find a chance of firing a shot. This fatal region was more than a desert. Animals themselves didn’t frequent it.

Fortunately, Robert discovered a bustard’s nest with a dozen large eggs in it, which Olbinett cooked under hot ashes. These, with a few roots of purslane which were growing at the bottom of a ravine, were all the breakfast of the 23rd.

The path became extremely difficult. The sandy plains were bristling with spinifex, a prickly plant which is called the “porcupine” in Melbourne. It tears clothing to rags, and makes the legs bleed. The courageous ladies never complained, but went on valiantly, setting an example, and encouraging each other with a word and a look.

They stopped in the evening at the foot of Bulla Bulla, on the banks of the Jungalla Creek. The supper would have been very scant, if MacNabbs had not killed a large rat, the Leporillus conditor, which has an excellent reputation, from the point of view of food. Olbinett roasted it, and it would have been pronounced even superior to its reputation had it equalled a sheep in size. They were obliged to be content with it, however, and it was devoured to the bones.

On the 24th the weary but still energetic travellers started off again. After circling around the foot of the mountain, they crossed long prairies where the grass seemed made of whalebone. It was a tangle of darts, a medley of sharp bayonets, and a path had to be cut through it, sometime with an axe, and sometimes by fire.

There was not even a question of breakfast that morning. Nothing could be more barren than this region strewn with quartz debris. Not only hunger, but thirst, was cruelly felt. The burning atmosphere intensified its assault. Glenarvan and his friends could only go half a mile an hour. Should this lack of food and water continue until evening, they would all sink on the road, never to rise again.

But when everything fails a man, and he finds himself without resources, at the very moment when he feels he must give up, then Providence steps in.

Water presented itself in the cephalotes plants, a species with cup-shaped flowers, filled with refreshing liquid, which hung from the branches of coralliform shrubs. They all quenched their thirst with these, and felt revived.

The only food they could find was the same as the natives were forced to subsist upon, when they could find neither game, nor snakes, nor insects. Paganel discovered a plant in the dry bed of a creek whose excellent properties had been frequently described by one of his colleagues in the Geographical Society.

It was nardoo, a cryptogamous plant of the family Marsileaceae, and the same which had prolonged the lives of Burke, Wills, and King in the deserts of the interior. Under its leaves, which resembled those of the clover, there were dried sporules as large as a lentil, and these sporules, when crushed between two stones, made a sort of flour. This was converted into coarse bread, which stilled the pangs of hunger at least. There was a great abundance of this plant growing in this place, and Olbinett gathered a large supply, so that they were sure of food for several days.

The next day, the 25th, Mulrady was able to walk part of the way. His wound was entirely closed. The town of Delegate was not more than ten miles off, and that evening they camped in longitude 149°, on the very frontier of New South Wales.

A fine, penetrating rain had been falling for a few hours. There would have been no shelter from this, but John Mangles chanced upon a deserted and dilapidated sawyer’s hut. It was necessary to be satisfied with this miserable hut of branches and stubble. Wilson wanted to kindle a fire to prepare the nardoo bread, and he went out to pick up the dead wood scattered all over the ground. But he found it would not light. The great quantity of aluminous material which it contained prevented all combustion. This was the incombustible wood Paganel had mentioned, in his list of strange Australian products.

They had to dispense with fire and bread,1 and sleep in their damp clothes while the laughing birds hidden in the high branches seemed to scoff at these unfortunate travellers.

The young women dragged themselves along, almost unable to walk

Glenarvan was nearly at the end of his sufferings, however. It was time for them to come to their end. The two young ladies were making heroic efforts, but their strength was hourly decreasing. They dragged themselves along, almost unable to walk.

Next morning they started at daybreak. At eleven o’clock, Delegate came in sight in Wellesley County, fifty miles from Twofold Bay.

Transportation was quickly arranged, there. Feeling so close to the coast, hope returned to Glenarvan’s heart. Perhaps there might have been some slight delay, and they might get there before the arrival of the Duncan, after all. In twenty-four hours they would reach the bay.

At noon, after a comfortable meal, the travellers all settled in a mail coach drawn by five strong horses. It left Delegate at a gallop.

The postilions, stimulated by the promise of a princely reward, drove rapidly along a well-kept road. They did not lose two minutes at the relays where they changed horses, which took place every ten miles. It seemed as if they were infected with Glenarvan’s zeal.

They ran at six miles an hour all day long, and through the night.

The next day, at sunrise, a low murmur announced their approach to the Pacific Ocean.2 It was necessary to go around the bay to reach the shore at the 37th parallel, the exact point where Tom Austin was to await their arrival.

When the sea appeared, all eyes anxiously gazed at the horizon. Was the Duncan, by a miracle of Providence, running close to the shore, as she had been a month ago when they reached Cape Corrientes, and they had found her on the Argentine coast?

They saw nothing. Sea and sky mingled in the same horizon. Not a sail enlivened the vast stretch of ocean.

One hope still remained. Perhaps Tom Austin had thought it necessary to cast anchor in Twofold Bay, for the sea was heavy, and a ship would not dare to venture near the shore.

“To Eden!” said Glenarvan.

Immediately the mail coach resumed the route around the bay, toward the small town of Eden, five miles away.

The postilions stopped not far from the lighthouse which marks the entrance of the port. Some ships were anchored in the harbour, but none of them bore the Malcolm flag at its masthead.

Glenarvan, John Mangles, and Paganel got out of the coach and rushed to the customs house, to inquire about the arrival of vessels within the last few days. No ship had arrived in the bay for a week.

“Perhaps the yacht has not left Melbourne, yet,” said Glenarvan, who did not wish to return to despair. “Perhaps we have arrived before her!’’

John Mangles shook his head. He knew Tom Austin. His first mate would never have delayed the execution of an order for ten days.

“I must know how things stand, in any event,” said Glenarvan. “Better certainty than doubt.”

A quarter of an hour later, a telegram was sent to the trustee of the shipbrokers in Melbourne. Then the party was driven to the Victoria Hotel.

At two o’clock a telegram was delivered to Lord Glenarvan.

LORD GLENARVAN, EDEN,

TWOFOLD BAY.

DUNCAN LEFT ON 18 TIDE. DESTINATION UNKNOWN.

J ANDREW SB

The telegram dropped from Glenarvan’s hands.

There was no doubt now. The honest Scottish yacht was now a pirate ship in the hands of Ben Joyce!

So ended this journey across Australia, which had commenced under such auspicious circumstances. All trace of Captain Grant and the castaways seemed to be irrevocably lost. This failure had cost the lives of a whole crew. Lord Glenarvan had been vanquished, and this courageous searcher, whom the unfriendly elements of the Pampas had been unable to stop, had been conquered on the Australian shore by the perversity of men.

End of Book Two

1. Possibly just as well. Improperly prepared nardoo is mildly toxic, and may have hastened the demises of Burke and Wills.

2. The Hetzel edition has “Indian” here, but this is definitely the Pacific coast of Australia.

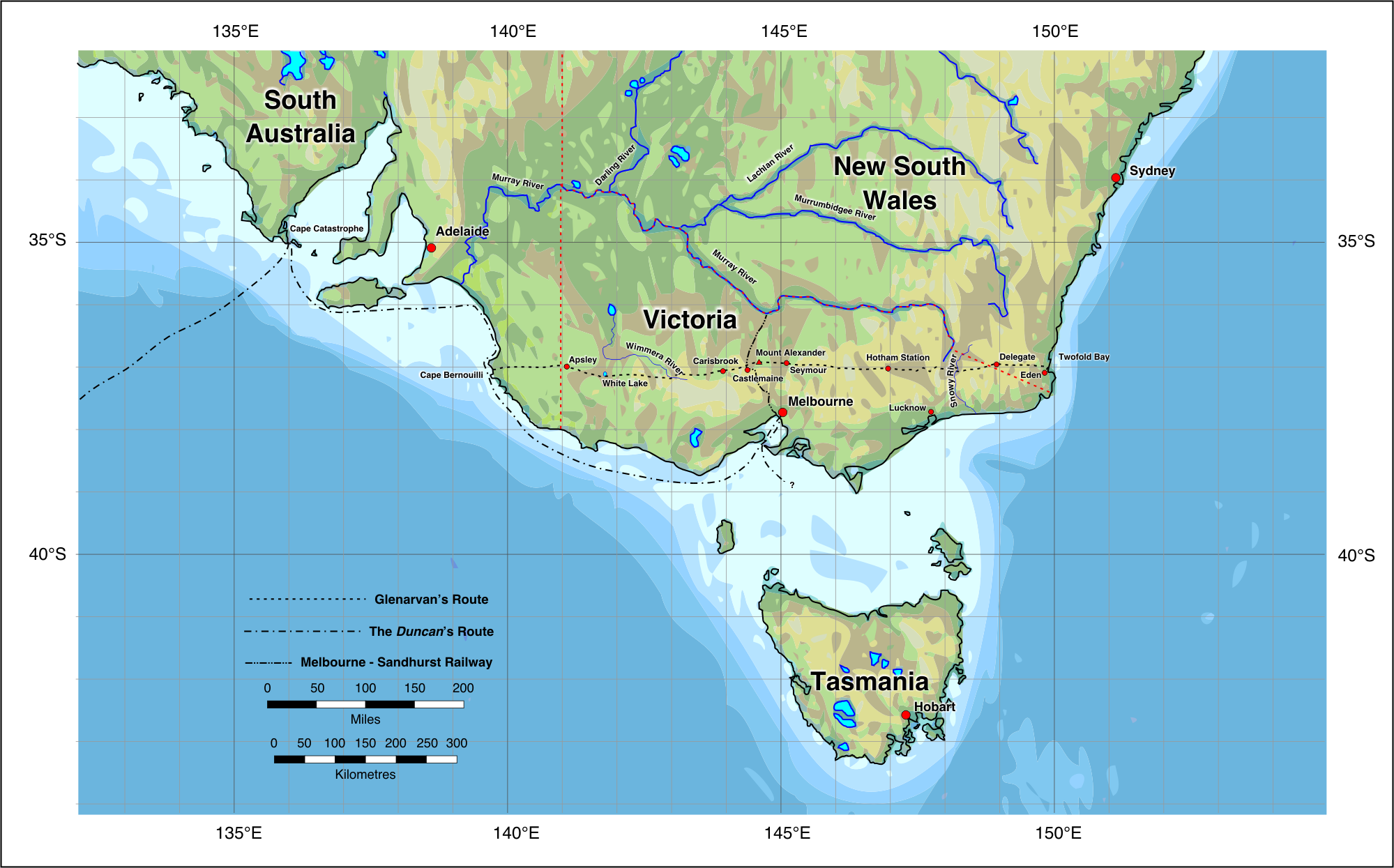

The searcher’s route across Australia at the 37th parallel