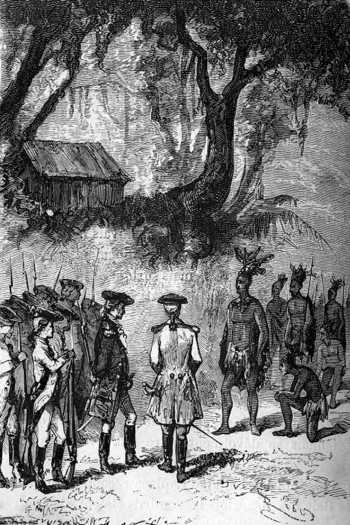

Seven canoes … attacked

The next day, January 27th, Macquarie’s passengers were seated in the brig’s narrow cabin. Will Halley had not offered his cabin to the ladies. The lack of manners was not regretted, because the den was worthy of the bear.

At half-past twelve, they sailed with the ebb-tide. The chain came taut and the anchor was laboriously torn from the bottom. There was a moderate southwest breeze. The sails were leisurely unfurled. The five men of the crew were moving slowly. Wilson wanted to help them, but Halley begged him to keep quiet and not to interfere with anything that did not concern him. He was used to getting by on his own, and did not ask for help, or advice.

This last was addressed to John Mangles, who had smiled at the awkwardness of the ship’s maneuvers. John took this in good stead, but privately reserved the right to intervene, if the clumsiness of the crew compromised the safety of the ship.

In time, and with much swearing from the master, the crew got the sails set. The Macquarie ran wide on the port tack, under her mainsails, topsails, topgallants, and jibs. Later, the studsails and royals were hoisted. But in spite of all the canvas, the ship made very little way. Her rounded bow, broad beam, and her heavy stern, made her a very bad sailer: the perfect type of tub.

It was necessary to put up with it. Fortunately, even as poorly as the Macquarie sailed, in five days, six at the most, she should reach Auckland harbour.

They lost sight of the coast of Australia and the lighthouse marking the port of Eden at seven o’clock in the evening. The ship laboured in a heavy sea; she rolled in the troughs between the waves. The violent gyrations made the passenger’s stay below deck uncomfortable, but they could not stay on deck because of the heavy rain. They were condemned to close confinement.

Everyone was left to their own thoughts. There was little talk. Lady Helena and Mary Grant barely exchanged any words. Glenarvan was restless. He paced back and forth, while the Major remained motionless. John Mangles, followed by Robert, occasionally climbed to the deck to watch the sea. As for Paganel, he murmured vague and incoherent words in his corner.

What was the worthy geographer thinking? Of New Zealand, to which destiny led him. He reviewed all of its history; the past of this sinister country replayed itself in his mind’s eye.

Was there in all this history a fact, an incident which could justify anyone calling these islands a “continent”? Could a modern geographer, or sailor, give them that name? Paganel’s thoughts always returned to the interpretation of the document. It was his obsession, an idée fixe. After Patagonia, after Australia, his imagination, triggered by a word, was bent on New Zealand. But one point, one, stopped him in this tracks. “‘Contin’ … ‘contin’ …” he repeated, “but that means continent!”

And he thought of all the sailors who had explored these two great islands of the southern seas.

It was on December 13th, 1642 that the Dutchman Tasman, after discovering Van Diemen’s Land, landed on the unknown shores of New Zealand. He followed the coast for a few days, and on the 17th his ships entered a large bay, terminated by a narrow strait between the two islands.

The North Island was called Te Ika-a-Māui by the natives, which means “Māui’s Fish”. The South Island is Te Waipounamu meaning “The Waters of Jade”.1

Abel Tasman sent his boats ashore, and they returned accompanied by two canoes carrying a noisy crew of natives. These savages were of medium size, brown and yellow skin, with protruding bones, gruff voices, and black hair tied up in a fashion similar to the Japanese, topped with a large white feather.

Seven canoes … attacked

This first meeting of Europeans and natives seemed to promise long-lasting friendly relations. But the next day, when one of Tasman’s boats was surveying an anchorage closer to the land, seven canoes carrying a large number of natives attacked it. The boat capsized and filled with water. The quartermaster who commanded it was struck in the throat with a roughly sharpened pike. He fell into the sea. Of his six companions, four were killed. The other two, and the quartermaster, swam back to the ships and were saved.

Tasman sailed following this incident, confining his vengeance to firing a few musket shots at the natives, that probably fell short. He left the bay, which is still called Massacre Bay,2 went up the west coast, and on the 5th of January he anchored near the northern tip of Te Ika-a-Māui. The violence of the surf, and the hostility of the natives prevented him from taking on water. He left these islands, to which he gave the name Staten Landt, that is to say, Land Of the States, in honour of the States General, the Dutch Parliament.

Indeed, the Dutch navigator imagined that they were connected to the islands of the same name discovered east of Tierra del Fuego, at the southern tip of America. He thought he had found “The Great Southern Continent.”

“But,” Paganel told himself, “what a sailor of the seventeenth century might call a ‘continent,’ a nineteenth-century sailor would not! Such a mistake is inadmissible! No! There is something that escapes me!”

For more than a century, Tasman’s discovery was forgotten, and New Zealand no longer seemed to exist, until a French navigator, Surville, became acquainted with it at 35° 37′ of latitude. At first he did not have any complaints about the natives, trading with them for fresh food to treat the crew’s scurvy. Several of Surville’s sailors were treated hospitably by a chief named Ranginui when a storm stranded them ashore at Whatuwhiwhi. All went well until a few days later when Surville accused Ranginui of stealing a yawl which had been cast adrift in the storm. Surville punished the robbery by burning the village, and kidnapping Ranginui, to take back to Europe with him.3 This terrible and unjust revenge was but a prelude to some of the bloody retaliations New Zealand was about to witness.

On the 6th of October, 1769, the illustrious Cook appeared on these shores

On the 6th of October, 1769, the illustrious Cook appeared on these shores. He anchored in Teoneroa Bay with his ship the Endeavour, and sought to rally the natives by good treatment. But to treat people well, you have to start by catching them. Cook did not hesitate to take two or three prisoners and impose his beneficence on them by force. These, loaded with presents, were then returned to the shore. Soon, several natives, enticed by their stories, came on board voluntarily and traded with the Europeans. A few days later Cook made his way to Hawke’s Bay, a large gulf on the east coast of the northern island. He found himself in the presence of belligerent, screaming, provocative natives. Their demonstrations went so far that it became necessary to calm them with a canister of grape shot.

On October 20th, the Endeavour anchored in Tokomaru Bay, where there lived a peaceful population of two hundred souls. The botanists on board made fruitful explorations in the country, and the natives transported them to the shore with their own canoes. Cook visited two villages defended by palisades, parapets and double ditches, which demonstrated serious knowledge of fortifications. The most important of these forts was situated on a rock which became an island at high tide. This was better than an island itself, for not only did the waters surround it, but they roared through a natural arch, sixty feet high, on which this inaccessible “pā” rested.

On the 31st of March, Cook, having, over five months, collected a vast harvest of curious objects, native plants, and ethnographic and ethnological documents, gave his name to the strait which separates the two islands, and left New Zealand. He would return in his later voyages.

In 1773, the great sailor reappeared at Hawke’s Bay and witnessed scenes of cannibalism. Here, we must reproach his companions for provoking them. Officers, having found the mutilated remains of a young savage on the beach, brought them on board, “broiled them,” and offered them to the natives, who threw themselves on them with voracity. It is a sad whimsy to be the cooks for a meal of cannibals!

Cook visited these lands which he particularly loved again on his third voyage, wishing to complete his hydrographic survey. He left them for the last time on February 25th, 1777.

In 1791, Vancouver lay for twenty days in Dusky Sound, without any profit for the natural or geographical sciences. D’Entrecasteaux, in 1793, explored twenty-five miles of coast in the northern part of Te Ika-a-Māui. The merchant captains, Hausen and Dalrympe, then Baden, Richardson, and Moodi, made brief visits, and Dr. Savage collected interesting details of the customs of the Māori, during a five-week stay.

It was in the same year, in 1805, that the nephew of the Chief of Rangihoua, the intelligent Duaterra, embarked on the Argo, anchored at the Bay of Islands, and commanded by Captain Baden.

Perhaps the adventures of Duaterra will provide an epic subject to some Māori Homer. They were fruitful in disasters, injustices, and ill-treatment. Bad faith, sequestration, blows and wounds are what the poor savage received in exchange for his good services. What an impression he must have formed of people who call themselves “civilized!” He was taken to London. He was made a sailor of the lowest class, the butt of the entire crew. Without Reverend Marsden, he would have died of grief. This missionary took an interest in the young savage, in whom he recognized a sound judgment, a brave character, and marvellous qualities of gentleness, grace, and affability. Marsden had his protege obtain some sacks of wheat and farming implements to take back to his own country. These were stolen. More misfortunes and the sufferings nearly overwhelmed the poor Duaterra again, before he managed to return to his homeland in 1814. He was just beginning to gather the fruits of so many hardships, when he died at the age of twenty-eight, just as he was about to regenerate this bloody Zealand. Civilization was undoubtedly delayed for many years by this irreparable misfortune. Nothing can replace an intelligent and good man, who combines in his heart the love of good with the love of his country!

New Zealand was abandoned until Thompson in 1816, Liddiard Nicholas in 1817, and Marsden in 1819, traversed various portions of the two islands, and in 1820 Richard Cruise, captain of the 84th Infantry Regiment, stayed for ten months, making valuable contributions to science, and learning the customs of the natives.

In 1824, Duperrey, commanding La Coquille, anchored in the Bay of Islands for a fortnight, and had nothing but praise for the natives.

After him, in 1827, the British whaler Mercury had to defend herself against looting and murder. The same year, Captain Dillon was greeted in the most hospitable way during two visits.

In March 1827, the commander of the Astrolabe, the illustrious Dumont D’Urville, spent a few nights with the natives, safely and unarmed. He exchanged presents and songs, slept in their huts, and undertook his survey work without being troubled, which resulted in such beautiful maps for the Navy Ministry.

It went otherwise the following year for the English brig Hawes, commanded by John James. After having touched the Bay Of Islands, he went on to the East Cape, and suffered greatly from a perfidious chief named Enararo. Several of his company suffered a terrible death.

Of these contradictory events, of these alternatives of mildness and barbarism, it must be concluded that too often the cruelties of the Māori were only reprisals. Good or bad treatment depended on good or bad captains. There were certainly some unjustified attacks by the natives, but they were more usually provoked by the Europeans. Unfortunately, the punishment fell on those who did not deserve it.

After D’Urville, the ethnography of New Zealand was completed by a daring explorer who circled the world twenty times. A nomad, a Bohemian of science, an Englishman, named Earle. He visited the unknown portions of the islands without having personal difficulties with the natives, but he was often a witness to scenes of anthropophagy. Māori devoured each other with disgusting sensuality.

This is also what Captain Laplace found in 1831, during his stay at the Bay of Islands. Already the wars were much more formidable, because the savages used firearms with remarkable precision. The once flourishing and populated lands of Te Ika-a-Māui changed into deep solitudes. Entire tribes had disappeared as herds of sheep disappeared, roasted and eaten.

The missionaries have struggled in vain to overcome these bloodthirsty tendencies. As early as 1808, the Church Missionary Society had sent its most able agents — it is the name that suits them — to the main stations of the northern island. But the barbarism of the Māori forced them to suspend the establishment of new missions. It wasn’t until 1815 that Messrs Marsden — the protector of Duaterra — Hall and King landed at the Bay of Islands, and bought two hundred acres of land from the chiefs for the price of twelve iron axes. This became the seat of Anglican society.

The beginnings were difficult, but the natives came to respect the life of the missionaries. They accepted their care and their doctrines. Some wild men softened. A feeling of gratitude awoke in these uncivilized hearts. In 1824, it even came to pass that the Māori protected their arikis,4 that is, the Reverends, against savage sailors who insulted and threatened them with ill-treatment.

Thus, with time, the missions flourished, despite the presence of convicts escaped from Port Jackson who demoralized the indigenous population. In 1831, the Gospel Missionary Newspaper reported two large settlements, one at Kidikidi, on the banks of a stream that runs to the sea in the Bay of Islands, the other in Paï-Hia, at the edge of the Kawa-Kawa River. The natives converted to Christianity had traced roads under the leadership of the arikis, cut tracks through the immense forests, and bridged the torrents. Each missionary would in turn preach the civilizing religion to the remote tribes, raising chapels of rushes or bark, schools for the young natives, and on the roof of these modest constructions unfurled the flag of the mission, carrying the cross of Christ and these words: “Rongo Pai”, that is to say “The Gospel”, in the Māori language.

Unfortunately, the influence of the missionaries did not extend beyond their missions. The whole nomadic part of the population escaped their operation. Cannibalism was destroyed only among Christians, and these new converts should not be subject to too great a temptation. The instinct for blood still pulses in them.

Moreover, a chronic state war still exists in in these savage countries. Māori are not stupid Australians fleeing the European invasion. They resist, they defend themselves, they hate their invaders, and an incurable hatred drives them at this moment against the English immigrants. The future of these great islands hangs on a throw of the dice. An immediate civilization awaits it, or a deep barbarism for long centuries, according to the chance of arms.

Thus Paganel, his brain boiling with impatience, had replayed in his mind the history of New Zealand. But nothing in this story gave a reason to call this country consisting of two islands a “continent.” And though a few words of the document had awakened his imagination, these two syllables ‘contin’ stubbornly blocked a new interpretation.

1. Another Māori name for the South Island is Te Waka a Māui “Māui’s Canoe.” Together the islands are known as Aotearoa “land of the long white cloud.”

The Hetzel note here was a ”correction” to the name Verne gives in the text, though Verne’s name for the South Island seems to be correct (allowing for variations in spelling.) I’ve updated all the names in the text to match current spelling — DAS

2. Tasman named it Moordenaar’s Bay “Murderers Bay”. It was the French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville who changed the name to Massacre Bay. With the discovery of gold in the region, it was renamed Golden Bay in the 1850s — DAS

3. Verne gives the chief the name of “Nagui-nouï”, and says that the yawl was stolen. What actually seems to have happened is that the boat had been cut adrift by the French after it got hung up on some rocks, and then salvaged by Ranginui, who by Māori custom, laid claim to it — DAS

4. Ariki is a Māori word meaning “person of the highest rank and seniority” so giving this title to the missionaries denoted their respect for them — DAS