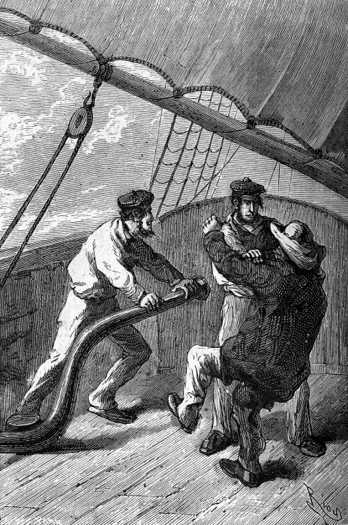

Mulrady and Wilson straightened the tiller more than once

On the 31st of January, four days after setting sail, Macquarie had not yet crossed two-thirds of the narrow sea between Australia and New Zealand. Will Halley did not pay much heed to the handling of his ship. He let her sail herself. He was rarely seen, not that anyone minded. It wasn’t even that objectionable that he spent all his time in his cabin, if only for the fact that the lout was drunk every day on gin or brandy. His sailors followed the example set by him, and no ship ever sailed more by the grace of God than the Macquarie of Twofold Bay.

Mulrady and Wilson straightened the tiller more than once

This unforgivable carelessness forced John Mangles to keep constant vigilance. Mulrady and Wilson straightened the tiller more than once as some sudden yaw nearly laid the brig on its side. Will Halley often berated the two sailors with strong swear words for their actions. In response, Mulrady and Wilson wanted to to confine the drunkard to the hold for the rest of the crossing. But John Mangles stopped them, and with some difficulty calmed their just indignation.

The situation of the ship worried him, but in order not to disturb Glenarvan, he only spoke of it to Major MacNabbs and Paganel. MacNabbs sided with Mulrady and Wilson.

“If you think it is necessary, John,” said MacNabbs, “you must not hesitate to take command, or at least take over the handling of the ship. This drunkard can become master again after we disembark at Aukland, and wreck it is his pleasure.”

“No doubt, Mr. MacNabbs,” said John, “and I will do it, if it is absolutely necessary. As long as we are at sea, a little supervision is enough. My sailors and I will not leave the deck. But, if Will Halley hasn’t sobered up when we approach the coast, I will be very uneasy.”

“Cannot you direct our course?” asked Paganel.

“It will be difficult,” said John. “Would you believe that there are no charts on board?”

“Really?”

“Really. The Macquarie only operates between Eden and Auckland, and Will Halley is so familiar with these waters, that he takes no bearings.”

“He imagines, no doubt,” said Paganel, “that his ship knows the way, and that she steers herself.”

John Mangles laughed. “I do not believe in self-sailing ships, and if Will Halley is drunk when we make landfall, he will put us in extreme danger.”

“Let us hope,” said Paganel, “that he will have recovered his reason in the neighbourhood of the land.”

“So, if he hasn’t, you could not guide the Macquarie to Auckland?” asked MacNabbs.

“Not without a map of this part of the coast. These shores are extremely dangerous. It is a succession of irregular and capricious little fjords, like the coast of Norway. There are numerous reefs, and it takes great experience to avoid them. A ship, however solid, would be lost if its keel struck one of those rocks submerged a few feet under water.”

“And in that case,” said the Major, “the crew would have no other recourse than to take refuge on the coast?”

“Yes, Mr. MacNabbs, weather permitting.”

“A bitter end!” said Paganel. “For the coasts of New Zealand are not hospitable, and the dangers of the interior are worse.”

“Are you talking about the Māori, Mr. Paganel?” asked John Mangles.

“Yes, my friend. Their reputation is known throughout the Pacific Ocean. It is not a question here of shy or stupid Australians, but of an intelligent and bloodthirsty race of cannibals, fond of human flesh. Of cannibals from whom no pity is to be expected.”

“So,” said the Major, “if Captain Grant had been shipwrecked on the coasts of New Zealand, you would not advise to search for him?”

“You might search the coasts for traces of the Britannia,” said the geographer. “But not the interior. No, that would be useless. Every European who ventures into these disastrous lands falls into the hands of the Māori, and every prisoner in the hands of the Māori is lost. I pushed my friends to cross the Pampas, to cross Australia, but I would never drag them onto the trails of New Zealand. May the hand of Heaven guide us; pray to God that we are never in the power of these ferocious natives!”

Paganel’s fears were only too justified. New Zealand has a terrible reputation, and its history is stained with bloody incidents.

The martyr-roll of navigators numbers many victims to the New Zealanders. Abel Tasman’s five sailors, killed and devoured, began these bloody annals of cannibalism. After him, Captain Tukney and all his crew of boatmen suffered the same fate. Towards the eastern part of the Strait of Foveaux, five fishermen of the Sydney Cove also found death at the teeth of the natives. We must also mention four men of the schooner Brothers, murdered at Molineux Harbour, several soldiers of General Gates, and three deserters of the Mathilda, to arrive at the so painfully famous name of Captain Marion du Fresne.

On May 11, 1772, after Cook’s first voyage, the French Captain du Fresne came to anchor at the Bay of Islands with his ship the Mascarin, accompanied by the Marquis de Castries, commanded by Captain Crozet.

The Māori gave an excellent welcome to the newcomers. At first they appeared timid, and it took many presents, kindnesses, and a long period of regular communication to put them at ease.

Their leader, the intelligent Te Kauri, belonged to the Wangaroa tribe, if Dumont D’Urville is to be believed, and he was a relative of the chief treacherously abducted by Surville, two years before the arrival of Captain du Fresne.

In a country where honour requires all Māori to obtain blood satisfaction for suffered outrages, Te Kauri could not forget the insult made to his tribe. He waited patiently for the arrival of a European ship, planned his revenge, and carried it out with a cold-blooded ruthlessness.1

After first simulating fear of the French, Te Kauri continued to lull them into a sense of false security. He and his comrades often spent the night aboard the ships. They brought gifts of fish. Their daughters and their wives often accompanied them. They soon learned the names of the officers and invited them to visit their villages. Du Fresne and Crozet, seduced by such advances, traveled all over this coast populated with four thousand inhabitants. The natives ran to meet them unarmed and sought to inspire them with absolute confidence.

Captain du Fresne, anchoring at the Bay of Islands, intended to replace the masts of the Marquis de Castries, badly damaged in a recent storm. He explored the interior of the country, and on the 23rd of May he found a magnificent cedar forest two leagues from the shore, and within reach of the bay a league from the ships.

A camp was established there where two-thirds of the crew, equipped with axes and other tools, worked to fell the trees and to build a road that led to the bay. Two other posts were chosen: one on the small island of Moturua, in the middle of the bay, where the sick of the expedition were transported along with the blacksmiths and coopers from the ships; the other on shore, a league and a half from the vessels. The shore camp was in communication with the carpenters’ encampment. Vigorous and helpful natives assisted the sailors in their various labours at all of these camps.

Captain du Fresne hadn’t overlooked taking some precautions. The savages were never allowed to bring weapons onto the ships, and the boats that went ashore were all well armed. But du Fresne and many of the most trusting of his officers were fooled by the conduct of the natives and the commander ordered that the boats be disarmed. Captain Crozet tried to persuade du Fresne otherwise, but he did not succeed.

After this, the attention and the devotion of the New Zealanders redoubled. Their chiefs and the French officers lived on a footing of perfect intimacy. Many times Te Kauri brought his son aboard, and let him sleep in the ship’s cabin. On the 8th of June, during a solemn visit to the shore, du Fresne was recognized as “grand chief” of the whole country, and he was crowned with four white feathers in his hair.

Thirty-three days had passed since the arrival of the ships at the Bay Of Islands. The work on the masts proceeded; the water tanks were filled with fresh water from Moturua. Captain Crozet personally directed the carpenters’ post, and there was every expectation of a successful enterprise.

On June 12th, at two o’clock, the commander’s boat was readied for a planned fishing trip near Te Kauri’s village. Du Fresne embarked with the two young officers, Vaudricourt and Lehoux, a volunteer, and twelve sailors. Te Kauri and five other leaders accompanied him. No one could predict the dreadful catastrophe that awaited fifteen out of the sixteen Europeans.

The crowded boat was rowed to shore, and was soon lost to sight from the two ships.

Captain du Fresne did not come back to the ship that evening. Nobody was worried about his absence. It was supposed that he had wanted to visit the masts yard and spend the night there.

The following day, at five o’clock, the Marquis de Castries longboat made its usual trip to the island of Moturua for fresh water. She returned on board without incident.

At nine o’clock the sailors of the Mascarin saw an almost exhausted man in the water, swimming toward the ships. A canoe went to his aid and brought him back.

It was Turner, one of the men who had gone with Captain du Fresne. He had two spear wounds in his side, and he alone, of the sixteen men who had left the ship the day before, returned.

He was questioned, and soon all the details of this horrible tragedy were known.

The unfortunate du Fresne’s boat had docked at seven o’clock in the morning. The savages came cheerfully to meet the visitors. They carried the officers and the sailors who did not want to get wet on their shoulders when they landed. Then the French separated from each other.

Immediately, the savages, armed with spears and clubs, rushed upon them, ten to one, and massacred them. The sailor Turner, struck with two spear-thrusts, was able to escape his enemies and hide in the undergrowth. From there he witnessed horrible scenes. The savages stripped the dead of their clothes, opened their bellies, and chopped them to pieces.

At this moment Turner, without being seen, threw himself into the sea, where he was retrieved by the Mascarin’s boat.

This event consternated the two crews. A cry of revenge broke out. But before avenging the dead, it was necessary to save the living. There were three posts on the shore, and thousands of angry savages, hungry cannibals, surrounded them.

In the absence of Captain Crozet, who had spent the night at the masts yard, Le Clesmeur, the first officer on board, took emergency measures. The Mascarin’s boat was dispatched with an officer and a detachment of soldiers. This officer must, above all, help the carpenters. He set off along the coast, saw Captain du Fresne’s boat grounded on the shore, and landed.

Captain Crozet, absent from the ship, and knowing nothing of the massacre, saw the detachment appear about two o’clock in the afternoon. He sensed that something was wrong, went to meet them, and learned the truth. He ordered that the others in the camp not be told what had happened, to prevent panic.

The savages, assembled in ranks, occupied all the heights. Captain Crozet recovered the main tools, buried the others, set fire to his sheds, and began his retreat with sixty men.

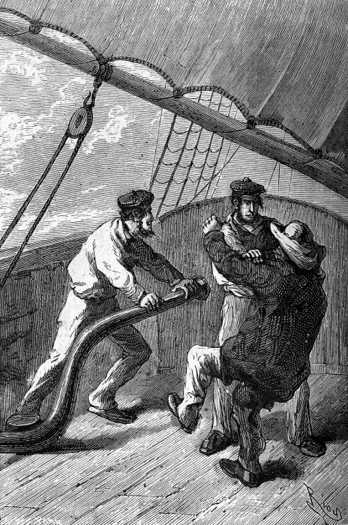

Four sailors, excellent marksmen

Natives followed him, shouting: “Te Kauri mate Marion!”2 They hoped to frighten the sailors by revealing the death of their Captain. This made the sailors so furious that Captain Crozet could barely hold them back. They crossed the two leagues to the shore, and embarked in the boats with the men of the second camp. During all this time, a thousand savages, sitting on the ground, did not move. But when the boats left the shore, the stones began to fly. At once, four sailors, good marksmen, successively shot down all the chiefs, to the great astonishment of the natives, who did not know the effectiveness of the firearms. Captain Crozet rallied to the Mascarin, and he immediately dispatched the boat to Moturua Island. A detachment of soldiers settled on the island to spend the night there, and the sick were returned to the ships.

The next day, a second detachment came to reinforce the post on the island. It was necessary to clear the island of the savages which infested it, and to continue to fill the barrels with water. The village of Moturua had three hundred inhabitants. The French attacked them. Six leaders were killed, the rest of the natives retreated from the French bayonets, and the village was burned. The Marquis de Castries could not return to the sea without masts, and Crozet, forced to abandon the trees of the cedar forest, had to make joined masts. The watering work continued.

A month passed. The savages made a few attempts to retake Moturua Island, but did not succeed. When their canoes came within range of the ships, they were cut down with cannon.

The work was finally completed. It remained to be seen if any of the sixteen victims had survived the massacre, and to avenge the others. The boat, carrying a large detachment of officers and soldiers, went to Te Kauri’s village. As they approached, this treacherous and cowardly leader fled, wearing Commander du Fresne’s coat over his shoulders. The huts in the village were carefully searched. In Te Kauri’s hut, they found the skull of a man who had been recently cooked. The impressions of the cannibals’ teeth were still visible on it. A human thigh was skewered on a wooden spit. A shirt with a bloody collar was recognized as belonging to du Fresne, then the clothes and pistols of the young Vaudricourt. They found the boat-arms and more tattered clothes. Further on, in another village, they found cleaned and cooked human entrails.

These irrefutable proofs of murder and cannibalism were collected, and the human remains respectfully buried. Then the villages of Te Kauri and Piki-Ore, his accomplice, were delivered to the flames. On the 14th of July, 1772, the two ships left these fatal shores.

The memory of this catastrophe must be foremost in the mind of every traveller who sets foot on the shores of New Zealand. It is a foolish captain who does not profit from these lessons. New Zealanders are still treacherous cannibals. Cook, in turn, recognized this well during his second voyage of 1773.

In fact, a boat from one of his vessels, the Adventure, commanded by Captain Furneaux, having landed on December 17th, in search of a supply of wild grasses, did not reappear. A midshipman and nine men had manned her. Captain Furneaux, anxious, sent Lieutenant Burney to look for them. When Burney arrived at their landing site he found “A picture of carnage and barbarism, of which it is impossible to speak without horror. The heads, the entrails, the lungs of many of our people, lay scattered on the sand, and, very near there, some dogs were still devouring other debris of this kind.”

To end this bloody list, we must add the ship Brothers, attacked in 1815 by the New Zealanders, and Captain Thompson and all the crew of the Boyd, massacred in 1820. Finally, on March 1st, 1829, at Whakatane, the leader Enararo looted the English brig Hawes from Sydney. His horde of cannibals slaughtered several sailors, cooked their corpses, and devoured them.

Such was the country of New Zealand to which the Macquarie sailed, manned by a stupid crew, under the command of a drunkard.

1. The basic outline of events about to be described follows pretty closely with the generally accepted account, but there is dispute about Te Kauri’s motives. Rather than his behaviour being a cold blooded, calculated deception from the start, some believe that relations between the French and the Māori were soured by series of offences against Māori traditions and beliefs by the French, and a growing feeling that the French were taking too much of the local resources in their provisioning and ship repair work. Eventually, Te Kauri decided that they’d gone too far, and decided to do something about it — DAS

2. “Te Kauri killed Marion.”