The work was begun

The first means of salvation attempted by John Mangles had failed. It was necessary to resort to the second without delay. It was obvious that the Macquarie could not be raised, and no less obvious that the only action to be taken was to abandon the ship. Waiting on board for unknown relief would have been recklessness madness. The Macquarie would be torn to pieces before the providential arrival of a ship at the scene of the grounding. The next storm, or even a strong surf raised by offshore winds, would roll her on the sands, break her, and scatter and disperse the debris. John wanted to be on land before this inevitable destruction.

He therefore proposed to build a raft large enough to carry the passengers, and a sufficient quantity of supplies, to the New Zealand shore.

The work was begun

No one argued with his decision. The work was begun, and they had made good progress when darkness forced them to stop work.

About eight o’clock in the evening, after supper, while Lady Helena and Mary Grant rested in their berths in the deckhouse, Paganel and his friends were discussing grave matters as they paced the deck of the ship. Robert did not want to leave them. This brave child listened attentively, ready to render any service, ready to devote himself to any perilous enterprise.

Paganel asked John Mangles if the raft could follow the coast to Auckland, instead of landing its passengers ashore. John replied that such a voyage was impossible with such an unwieldy vessel.

“And what we can not attempt on a raft,” said Paganel, “could it have been done with the brig’s dinghy?”

“Yes, eventually,” said John Mangles. “But we’d have to sail by day and anchor by night.”

“So, those wretches who have abandoned us…”

“Oh, them,” said John Mangles. “They were drunk, and in the darkness I fear that they have paid with their lives for their cowardly abandonment.”

“Too bad for them,” said Paganel, “and too bad for us, for the boat would have been very useful.”

“What do you want, Paganel?” said Glenarvan. “The raft will take us to the shore.”

“That is precisely what I would have liked to avoid,” said the geographer.

“What! A journey of ninety miles at the most after what we have done in the Pampas, and across Australia. Can it frighten men who have been through such hardships?”

“My friends,” said Paganel, “I do not question your courage, or the valour of our companions. Ninety miles would be nothing in any other country but New Zealand. You will not suspect me of pusillanimity. I was the first to to encourage you to cross America, and Australia. But here, I repeat, anything is better than venturing into this treacherous country.”

“Anything is better than exposing yourself to certain death on a stranded ship,” said John Mangles.

“What do we have to fear so much in New Zealand?” asked Glenarvan.

“The Māori,” said Paganel.

“The Māori!” said Glenarvan. “Can we not avoid them, following the coast? Moreover, an attack of a few miserable beings can not worry ten Europeans well armed and determined to defend themselves.”

“They are not miserable,” said Paganel, shaking his head. “The Māori are terrible tribes who fight against English rule — against their invaders — who often defeat them, and who always eat them!”

“Cannibals!” cried Robert. “Cannibals!” Then they heard him murmuring “My sister! Lady Helena!”

“Do not be afraid, my child,” said Glenarvan, to reassure the boy. “Our friend Paganel exaggerates!”

“I’m not exaggerating anything!” said Paganel. “Robert has shown that he is a man, and I treat him as a man, by not hiding the truth. New Zealanders are the most cruel, if not the most greedy, of cannibals. They devour everything that comes their way. For them, war is a hunt for that tasty game called man, and it must be admitted that it is a more logical reason to make war. Europeans kill their enemies and bury them. The savages kill their enemies and eat them, and, as my compatriot Toussenel said so well ‘It is not so evil to roast an enemy when he is dead, as to kill him when he does not want to die.’”

“Paganel,” said the Major, “there is much to discuss, but this is not the time. Whether it is logical or not to be eaten, we do not want to be eaten. But how has Christianity not yet destroyed these anthropophagous habits?”

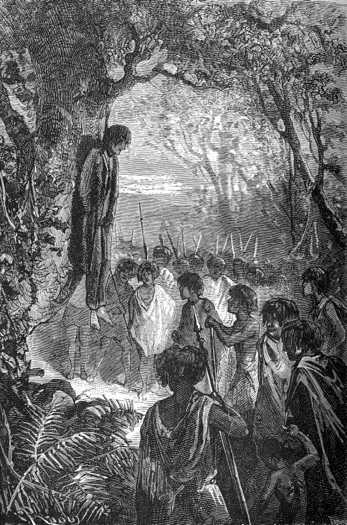

The martyrdom of Reverend Walkner

“Do you believe, then, that all New Zealanders are Christians?” said Paganel. “It is only a small minority, and the missionaries are still and too often victims of these brutes. Last year, Reverend Walkner was martyred with horrible cruelty.1 The Māori hanged him. Their wives snatched out his eyes. They drank his blood; they ate his brains. And this murder took place in 1865, in Opotiki, a few leagues from Auckland, right under the eyes of the English authorities. My friends, it takes centuries to change the nature of a race of men. What the Māori have been, they will be for a long time yet. Their whole history is made of blood. How many crews have they slaughtered and devoured, from the sailors of Tasman to the sailors of the Hawes? And it is not the white man’s flesh that has whetted their appetites. Long before the arrival of the Europeans, the Māori satisfied their appetites at the cost of murder. Many travellers who have lived among them have attended cannibal feasts where the guests were driven by the desire to eat a delicacy, like the flesh of a woman or a child!”

“Bah!” said the Major. “Aren’t these accounts just traveller’s tales? We like to come back from dangerous countries telling of narrow escapes from the stomachs of cannibals!”

“I’m not exaggerating,” said Paganel. “Very reliable witnesses have spoken: the missionaries Kendall, and Marsden; Captains Dillon, D’Urville, Laplace, and others. And I believe their stories; I must believe it. Māori are cruel by nature. On the deaths of their leaders, they immolate human victims. They claim that these sacrifices appease the anger of the deceased, who could strike the living, and at the same time offer him servants for the next life! But as they eat these posthumous servants, after having massacred them, one is justified in believing that the stomach motivates them more than superstition.”

“However,” said John Mangles. “I imagine that superstition plays a role in the scenes of cannibalism. Therefore, as religion changes, manners will change too.”

“John, my good friend,” said Paganel. “You raise the significant question of the origin of anthropophagy. Is it religion, or is it hunger that has driven men to devour each other? This is just idle speculation, right now. Why does cannibalism exist? The question is not yet resolved, but it exists. This is an important fact, about which we have only too much reason to be concerned.”

Paganel was correct. Anthropophagy has been chronic in New Zealand, as in Fiji and the Torres Strait. Superstition obviously influences these odious customs, but there are cannibals because there are times when game is rare and hunger is great. The savages began by eating human flesh to satisfy the requirements of a rarely satiated appetite. Then, the priests regulated and sanctified these monstrous habits. The meal became a ceremony. That is all.

In the eyes of Māori, nothing is more natural than eating each other. Missionaries often asked them about cannibalism. They asked them why they devoured their brothers. To which the chiefs replied that fish eat fish, that dogs eat men, that men eat dogs, and that dogs eat each other. In their very theogony, legend relates that a god ate another god. With such precedents, how can one resist the pleasure of eating one’s neighbour?

Moreover, the Māori claim that by devouring a dead enemy one consumes their spirit. Thus one inherits the other’s soul, their strength, their worth, which are particularly enclosed in the brain. This accounts for the brain being a choice dish, reserved for the most honoured guest.

However, Paganel argued — not without reason — that sensuality, especially hunger, excited the zealots to anthropophagy, and not only the savages of Oceania, but the savages of Europe.

“Yes,” he added, “Cannibalism has long reigned among the ancestors of the most civilized peoples, and do not take this personally, especially among the Scots.”

“Really?” asked MacNabbs.

“Yes, Major,” said Paganel. “When you read some passages by Saint Jerome on the Attacotti of Scotland, you will see what to think of your ancestors! And without going back to pre-historical time, during the reign of Elizabeth, at the very time when Shakespeare was dreaming of his Shylock, was not the Scottish bandit Sawney Bean executed for the crime of cannibalism? And what was his reason for eating human flesh? Religion? No. Hunger.”

“Hunger?” asked John Mangles.

“Hunger,” replied Paganel, “but above all, the necessity for the carnivore to renew its flesh and blood by the nitrogen contained in animal flesh. The lungs are satisfied with a provision of tuberous and starchy plants. But if you want to be strong and active you must absorb those malleable foods that repair the muscles. As long as the Māori are not members of the society of the legumists, they will eat meat and, for meat, human flesh.”

“Why not the meat of animals?” asked Glenarvan.

“Because they have no animals,” said Paganel, “and you must know it, not to excuse, but to explain their habits of cannibalism. Quadrupeds, even birds, are rare in this inhospitable country. So the Māori have always fed on human flesh. There are even ‘seasons to eat men,’ as in civilized countries, seasons for hunting. Then there are the great battues, that is, the great wars, and entire tribes are served on the table of the victors.”

“Thus,” says Glenarvan, “according to you, Paganel, cannibalism will not disappear until the day when sheep, oxen, and pigs swarm in the meadows of New Zealand.”

“Of course, my dear Lord, and it will take years for the Māori to get rid of their preference for Māori flesh, for the sons will long enjoy what their fathers loved. According to them, this flesh tastes like pork, but with more aroma. As for white flesh, they are less fond of it, because the whites mix salt with their food, which gives them a peculiar flavour, little liked by the gourmets.”

“They are discerning!” said the Major. “But whether white or black flesh, do they eat it raw or cooked?”

“What does it matter to you, Mr. MacNabbs?” asked Robert.

“Now then, my boy,” replied the Major, seriously, “If I ever end up in the teeth of a cannibal, I prefer to be cooked!”

“Why?”

“To be sure of not being devoured alive!”

“Good, Major!” said Paganel. “But suppose that they cooked you alive?”

“The fact is,” said the Major, “that I would not give a half crown for the choice.”

“In any case, MacNabbs, and if it is agreeable to you,” said Paganel, “the New Zealanders only eat flesh when it is cooked or smoked. They are well informed people on matters of their cuisine. But, for me, the idea of being eaten is particularly unpleasant! Finish your existence in the stomach of a savage? Ugh!”

“The conclusion of all this,” said John Mangles, “is that we must not fall into their hands. Let’s also hope that one day Christianity will have abolished these monstrous customs.”

“Yes, we must hope so,” said Paganel. “But, believe me, a savage who has tasted human flesh will hardly give it up. Judge for yourself by these two stories.”

“Let’s hear the stories, Paganel,” said Glenarvan.

“The first is reported in the chronicles of the Jesuit society in Brazil. A Portuguese missionary once met a very sick Brazilian woman. She had only a few days to live. The Jesuit taught her the truths of Christianity, which the dying woman accepted without discussion. Then, after the food of the soul, he thought to give her the food of the body, and offered his penitent some European delicacies. ‘Alas!’ answered the old woman, ‘My stomach can not support any kind of food. There is only one thing I would like to taste; but, unfortunately, no one here could procure it for me.’ — ‘What is it?’ asked the Jesuit. — ‘Ah! My son! It’s the hand of a little boy! It seems to me that I could nibble on the little bones with pleasure!’”

“Ah, but is it good?” asked Robert.

“My second story will answer you, my boy,” said Paganel. “One day, a missionary reproached a cannibal for this horrible custom, contrary to the divine laws against eating human flesh. ‘And besides, it must taste awful!’ he added. — ‘Ah, Father!’ replied the savage, casting a covetous glance at the missionary, ‘Say that God forbids it, but do not say it’s awful! If only you would try it!’”

1. Reverend Carl Sylvius Völkner was captured by the Māori, and executed as an English spy (which he arguably was) — DAS