The capsized dinghy was brought alongside

The facts reported by Paganel were indisputable. The cruelty of the Māori could not be doubted, so there was danger in landing there. But had the danger been a hundred times greater, it was necessary to face it. John Mangles felt that they should leave the ship destined for imminent destruction without delay. There could be no hesitation between the two dangers, the one certain, the other only probable.

It could not reasonably be expected that they would be rescued by a ship. The Macquarie was not on the shipping lanes used to land in New Zealand. They go to Auckland in the north, or New Plymouth in the south, but the stranding had taken place precisely between these two points, on the deserted part of the shores of Te Ika-a-Māui. It was a bad coast, dangerous, badly haunted. Ships have no other problem than to avoid it, and, if the wind carries them here, to leave again as quickly as possible.

“When will we leave?” asked Glenarvan.

“Tomorrow morning at ten o’clock,” said John Mangles. “The tide will be rising, and it will carry us to the shore.“

The next day, February 5th, at eight o’clock, the construction of the raft was completed. John had given all his care to the construction of it. The raft built from the the remains of the foremast which had been used to place the anchors was not large enough to carry all the passengers and provisions. They needed a sturdy, steerable vehicle, capable of navigating over nine miles of sea. The main mast alone could provide the materials needed for its construction.

Wilson and Mulrady set to work. The rigging deadeyes were cut away, and the main mast was felled, chopped down with an axe at its base. It fell over the starboard railing, which shattered under its impact. The Macquarie was then stripped like a hulk.

The lower yards, with the yards from the topsails and topgallants were sawn and split to make up the main frame of the raft. They were combined with the pieces of the foremast, and all these spars were firmly bound together. John was careful to fill in gaps between the spars with half a dozen empty barrels, to float the raft higher in the water.

On this strong foundation, Wilson laid a latticework floor made of grating. Any waves that broke over the raft would thus drain away, and the passengers could keep dry. Moreover, water barrels, solidly joined, formed a kind of circular bulwark which protected the deck against large waves.

That morning, John, seeing the favourable wind, placed the small topgallant’s yard as a mast in the centre of the raft. It was held by stays and equipped with a makeshift sail. A large oar with a wide blade, attached at the rear, made it possible to steer the rig, if the wind gave it sufficient speed.

Such a raft, under the best conditions, could resist the force of the waves. But could it be steered, or brought to the coast at all, if the wind turned? That was the question. They began the loading at nine o’clock.

First they stowed sufficient provisions to last as far as Auckland, so it wouldn’t be necessary to rely on the productions of this ungrateful land.

Olbinett’s remaining stores, purchased for the crossing of the Macquarie, provided a few preserved meats, but little remained of them. They had to rely on the provisions from the brig: mediocre quality sea biscuits, and two barrels of salted fish. The steward was ashamed of it.

These provisions were enclosed in hermetically sealed cases, impervious and impenetrable to sea water, then lowered to the raft and lashed to the foot of the makeshift mast. The weapons and ammunition were put in a safe and dry place. Fortunately, the travellers were well armed with rifles and revolvers.

The small anchor was also loaded in case they were unable to reach the shore on the first tide, and they had to anchor offshore.

At ten o’clock the tide began to make itself felt. The breeze was blowing weakly from the northwest. A slight swell rippled the surface of the sea.

“Are we ready?” asked John Mangles.

“Everything is ready, Captain,” answered Wilson.

“All aboard!” John shouted.

Lady Helena and Mary Grant descended a coarse rope ladder, and settled at the foot of the mast on the crates of provisions, their companions near them. Wilson took the helm. John placed himself on the sail tackle, and Mulrady cut the mooring that held the raft to the side of the brig.

The sail was deployed, and the raft began to move toward the shore under the double action of the tide and the wind.

The coast was nine miles away, a mediocre distance that a boat with good oars could cover in three hours. But with the raft, it would take longer. If the wind held, they might reach the land in a single tide. But if the breeze calmed, the ebb tide would prevail, and it would be necessary to anchor to wait for the next tide. That was John Mangles’ chief concern, and it filled him with apprehension.

Still, he hoped to succeed. The wind freshened. The tidal flow having commenced at ten o’clock, they must reach the shore by three o’clock, or they would have to anchor to avoid being carried out to sea on the ebb.

The beginning of the crossing went well. Little by little, the black heads of the reefs and the yellow carpets of the sandbanks disappeared under the rising tide and the waves. Great attention and skill were necessary to avoid these submerged shoals, and to direct a rig that was slow to respond to its rudder.

At noon they were still five miles from the coast. A clear sky allowed them to distinguish the main landmarks. In the northeast stood a mountain over three thousand feet high. It stood out on the horizon in a strange way, and its silhouette mimicked the grimacing profile of a monkey’s head, facing the sky. It was Mount Pirongia, precisely located on the 38th parallel, according to their map.

At half-past twelve Paganel pointed out that all the rocks had disappeared under the rising tide.

“Except one,” said Lady Helena.

“Where, Madame?” asked Paganel.

“There.” Lady Helena pointed to a black dot a mile ahead.

“Indeed,” said Paganel. “Let’s mark its position, we don’t want to strike it, after it is submerged.”

“It is precisely in line with the northern ridge of the mountain,” said John Mangles. “Wilson, make sure to give it a wide birth.”

“Yes, Captain,” said the sailor, leaning his full weight on the steering oar at the stern.

In half an hour they had gained half a mile. But, strangely enough, the black spot was still showing above the waves.

John was watching it attentively. He borrowed Paganel’s telescope to see it better.

“It is not a reef,” he said, after a moment’s examination. “It’s something floating. It goes up and down with the swell.”

“Is it a piece of Macquarie’s masts?” asked Lady Helena.

“No,” said Glenarvan. “No debris could have drifted so far from the ship.”

“Wait!” exclaimed John Mangles, “I recognize it. It’s the boat!”

“The brig’s dinghy?” asked Glenarvan.

“Yes, My Lord. The brig’s dinghy, capsized!”

“Those poor men!” exclaimed Lady Helena. “They perished!”

“Yes, Madame,” said John Mangles. “They must have perished, for in the midst of these breakers, on a stormy sea, on that black night, they were running to certain death.”

“May Heaven have pity on them!” murmured Mary Grant.

For a few moments the passengers remained silent. They looked at the frail boat they were approaching. It had evidently capsized four miles from the shore, and of those who had gone in her, no doubt no one had escaped.

“But this boat may be useful,” said Glenarvan.

“Indeed,” said John Mangles. “Steer for it, Wilson.”

The raft changed direction, but the breeze fell gradually, and the boat was not reached before two o’clock.

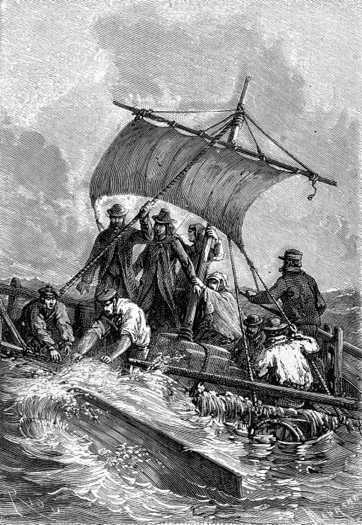

The capsized dinghy was brought alongside

Mulrady, placed at the front, fended off the impact, and the capsized dinghy was brought alongside.

“Empty?” asked John Mangles.

“Yes, Captain,” said the sailor. “The boat is empty, and its seams have been opened. It won’t be any use to us.”

“No use at all?” asked MacNabbs.

“None,” said John Mangles. “It’s only good to burn.”

“I regret it,” said Paganel. “For that dinghy could have taken us to Auckland.”

“We must resign ourselves, Mr. Paganel,” said John Mangles. “Moreover, on a rough sea, I still prefer our raft to that fragile boat. It took only a small blow to tear it to pieces! So, My Lord, we have nothing left to do here.”

“When you’re ready, John,” said Glenarvan.

“On the way, Wilson,” said the young captain. “Straight for the coast.”

The tide continued to rise for about an hour. They crossed a distance of two more miles. But the breeze fell almost entirely and tended to swing around away from the shore. The raft remained motionless. Soon it began to drift toward the open sea under the pressure of the ebb. John could not hesitate for a moment.

“Drop the anchor!” he ordered.

Mulrady had been expecting the order, and was ready. He dropped the anchor in five fathoms of water. The raft retreated two fathoms before the hawser pulled taut. They furled their makeshift sail, and settled down for a long wait.

Indeed, the tide was not to turn again before nine o’clock in the evening, and since John Mangles did not care to sail during the night, he planned to stay anchored there until five o’clock the next morning. The land was in sight just three miles off.

The waves, raised by a strong swell, seemed to be moving constantly toward the shore. Glenarvan, when he learned that the whole night would be spent on board the raft, asked John why he was not taking advantage of the waves to carry them closer to land.

“Your Honour is deceived by an optical illusion,” said the young captain. “Although the swell seems to carry the water landward, the water doesn’t move at all. It’s a balancing of liquid molecules, nothing more. Throw a piece of wood in the middle of these waves, and you will see that it will remain stationary, except for the motion from the ebb tide. We must remain patient.”

“And dinner?” asked the Major.

Olbinett drew a few pieces of dry meat and a dozen biscuits from a box of provisions. The steward blushed to offer his masters such a small menu, but it was accepted with a good grace, even by the ladies, who had not much appetite, owing to the violent motions of the raft.

This motion, produced by the jerking of the raft on its cable in the swells, was very tiring for all. The raft was incessantly tossed on the small and capricious waves as violently as if it was striking an underwater rock. It was sometimes hard to believe that they weren’t aground. The hawser was stretched taut, and every half an hour John pulled in a fathom to refresh it. Without this precaution, it would inevitably have broken, and the raft, cast adrift, would have been lost.

John’s apprehensions was easily understood. His cable could break, or his anchor slip, and in either case, they would be in trouble.

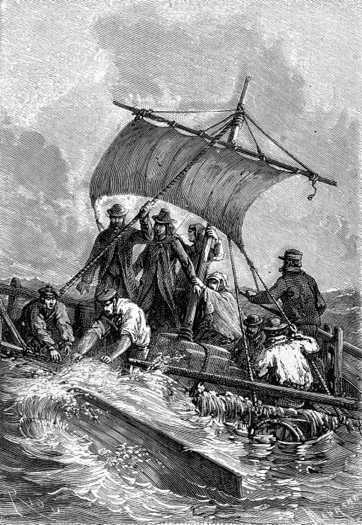

The night was approaching

The night was approaching. Already, the disc of the sun, blood red, and flattened by refraction, was disappearing behind the horizon. The last lines of water shone in the west and glittered like sheets of silver. To that side, everything was sky and water, except for one clearly marked point: the hulk of the Macquarie motionless on its shoal.

The short twilight delayed the onset of darkness by a few minutes, and soon the shore, which bounded the horizons of the east and the north, melted into the night.

The shipwrecked party were left in an anxious situation on this narrow raft, lost in the shadows of night. Some fell into disturbed slumber and bad dreams; the others could not find an hour of sleep. At daybreak, everyone was drained by the fatigues of the night.

With the rising tide, the wind resumed from the open sea. It was six o’clock in the morning. Time was pressing. John had arranged everything to get a quick start. He ordered that the anchor be weighed. But the anchor flukes, under the shaking of the cable, had deeply embedded in the sand. Without a windlass, and even with the tackle Wilson rigged, it was impossible to pull it off.

Half an hour passed in futile attempts. John, impatient to sail, had the line cut, abandoning his anchor and taking away any opportunity to moor in an emergency, or if this tide was not enough to reach the coast. But he did not want to wait any longer, and an axe delivered the raft to the breeze, helped by a current of two knots.

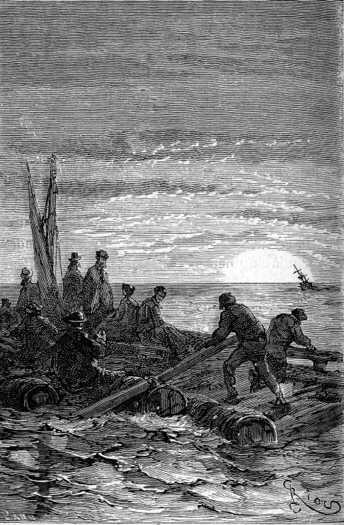

The sail was spread. They drifted slowly toward the shore, which was fading into greyish masses against a background of sky illuminated by the rising sun. The reefs were deftly avoided and doubled. But, under the uncertain breeze from the open sea, the raft did not seem to approach the shore. How difficult was it to land on this dangerous shore?

At nine o’clock, the coast was less than a mile away. The breakers bristled on a steep shore. It was necessary to discover a practicable landing there. The wind gradually weakened and fell completely. The sail flapped uselessly against the mast. John had it furled. The tide alone carried the raft to the land, but they could no longer steer it, and enormous bands of seaweed slowed their progress.

At ten o’clock the raft was almost stationary, three cables from the shore. With no anchor, were they going to be pushed back by the ebb? John, his hands clenched, his heart devoured with anxiety, cast a fierce glance at this unapproachable land.

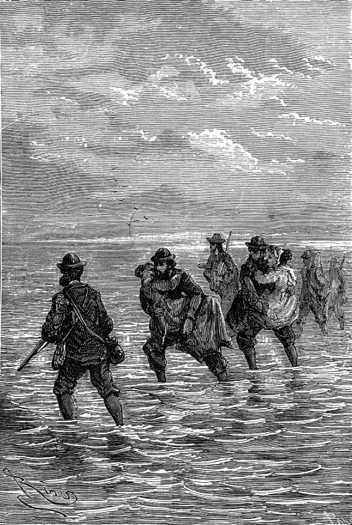

The ladies, carried from arm to arm

Fortunately — fortunately this time — they felt a shock. The raft stopped. It had run aground on a sandy bottom, twenty-five fathoms from the coast.

Glenarvan, Robert, Wilson, and Mulrady threw themselves into the water. The raft was moored to some neighbouring rocks. The ladies, carried from arm to arm, reached the shore without having wetted a fold of their dresses, and soon all, with arms and provisions, had at last set foot on these formidable shores of New Zealand.