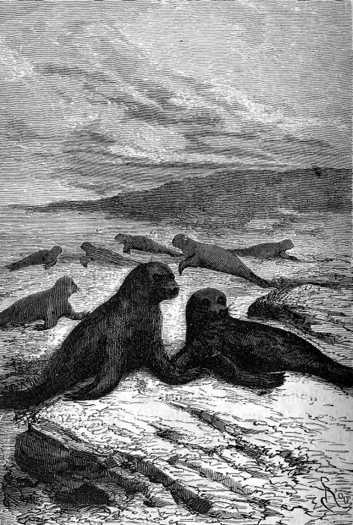

Seals, with their rounded heads

On the 7th of February, at six o’clock in the morning, Glenarvan gave the signal to depart. The rain had stopped during the night. The sky, overcast with thin greyish clouds, stopped the rays of the sun three miles above the ground. The moderate temperature made it possible to face the trials of a journey by day.

Paganel had measured the distance between Kawhia Point and Auckland on the map as eighty miles. It would be an eight-day trip, at ten miles a day. But instead of following the winding shores of the sea, it seemed to him a better idea to head for the village of Ngaruawahia, at the confluence of the Waikato and Waipa rivers, thirty miles away. The Overland Mail Track — more a trail than a road, but passable to carriages — passed through it on its route from Napier, on Hawke’s Bay, to Auckland. From there it would be easy to reach Drury and rest in an excellent hotel that the geologist Dr. von Hochstetter particularly recommended.

The travellers, each carrying a share of their provisions, began to follow the shore of Aotea Bay. As a precaution, they stayed close together, and they watched the undulating plains to the east with their loaded rifles at the ready. Paganel, with his excellent map in hand, took professional pleasure in noting the accuracy of its every detail.

During part of the day, the little troop walked over sand composed of fragments of bivalve shells and cuttlebone, mixed with magnetite and hematite iron oxides. A magnet held close to the ground would instantly be covered with brilliant crystals.

Seals, with their rounded heads

On the shore, caressed by the rising tide, were a few marine animals that made no effort to flee. The seals, with their rounded heads, broad, curving foreheads, and expressive eyes, presented a sweet and even affectionate appearance. It was easily understood why fables romanticized these curious inhabitants of the waves, making them out to be enchanting sirens, though their true voices were an inharmonious growl. These animals, numerous on the coasts of New Zealand, are the object of an active trade. They are caught for their oil and fur.

Between them were three or four, blue-grey elephant seals, twenty-five or thirty feet long. These huge amphibians, lazily stretched out on thick beds of giant kelp, raised their flexible trunks and grimly waggled the rough bristles of their long and twisted moustaches: curly corkscrews like the beard of a dandy. Robert was amusing himself by contemplating this interesting world, when he exclaimed “Hey! Those seals are eating pebbles!”

And, indeed, many of these animals were greedily swallowing the stones from the shore.

“Parbleu! You’re right!” said Paganel. “It can not be denied that these animals graze the pebbles of the shore.”

“A strange food,” said Robert, “and difficult to digest!”

“It’s not for food, my boy, but for feeding itself, that these amphibians are swallowing stones. It is a way to increase their specific gravity to easily dive to the bottom of the sea. Once back on the land, they will regurgitate these stones without further ceremony. You will soon see these seals dive under the waves.”

Soon, indeed, half a dozen seals, sufficiently weighted, dragged themselves down the shore and disappeared into the water. But Glenarvan could not waste precious time waiting for their return to watch the unloading operation and, to Paganel’s great regret, the interrupted march was resumed.

At ten o’clock, they stopped for lunch at the foot of large rocks of basalt arranged like Celtic dolmens on the edge of the sea. An oyster bed provided a large quantity of these molluscs. These oysters were small and unpleasant tasting, but following Paganel’s advice, Olbinett cooked them on hot coals, and thus prepared, they were eaten by the dozens and dozens for the duration of the meal.

After finishing their lunch, they continued to follow the bay shore. On its jagged rocks, at the tips of the sharp peaks at the tops of its cliffs, a whole world of sea birds: frigates, boobies, gulls, and large immobile albatrosses had taken refuge. At four o’clock in the evening, ten miles had been crossed without difficulty or fatigue. The ladies asked to continue their walk until evening. At this point, in order to reach the Waipa valley, it was necessary to divert their path away from the sea, around the foot of some mountains which appeared to the north.

From a distance, the ground looked like an immense meadow that stretched as far as the eye could see, and promised an easy walk. But when the travellers arrived at the edge of these green fields, they were very disillusioned. The pasture gave way to a thicket of bushes with small white flowers, intertwined with the tall and innumerable ferns that the lands of New Zealand are particularly fond of. It was necessary to cut a path through these woody stems, which was hard work. However, they had passed around the first ridges of the Hakarimata Ranges by eight o’clock in the evening, and they stopped to camp for the night.

After a trek of fourteen miles, it was permissible to think of rest. Besides, there was neither a wagon nor a tent, so it was at the foot of the magnificent Norfolk pines that everyone prepared to sleep. They had plenty of blankets from which to improvise their beds.

Glenarvan took rigorous precautions for the night. They took turns keeping watch until daybreak, in well armed pairs. No fire was lit. Such glowing barriers are useful against wild beasts, but New Zealand has no tigers, lions, or bears, no ferocious animals of any sort; the New Zealanders, make up for the lack. A fire would only serve to attract such two-legged jaguars.

The night passed well, except for a few sand fleas, ngamu in the native language, the sting of which was very disagreeable, and an audacious family of rats that nibbled on their provision sacks.

The next day, February 8th, Paganel awoke feeling more confident and almost reconciled with the country. The Māori, whom he particularly feared, had not appeared, and these ferocious cannibals had not even threatened him in his dreams. He expressed his satisfaction to Glenarvan.

“I think that this little walk will be completed without difficulty,” he said. “Tonight we will have reached the confluence of the Waipa and the Waikato, and from there, meeting the natives is to be little feared on the road to Auckland.”

“How far do we have to go, to reach the confluence?” asked Glenarvan.

“Fifteen miles. About the same as we did yesterday.”

“But we will be very delayed if these endless forests continue to obstruct our way.”

“On the contrary,” said Paganel. “We will soon reach the Waipa, and there shouldn’t be any obstacle to us following its banks.”

“Let’s go, then,” said Glenarvan, who saw that everyone was ready to set out.

The forest further delayed their progress during the first hours of the day. Neither carriage nor horses could have passed where the travellers passed. They did not regret not having their Australian wagon. Until the day when motorized roads are built through its forests, it will only be practical for pedestrians to travel in New Zealand. The ferns, whose species are innumerable, compete with the same obstinacy as the Māori in defence of their native soil.

The little troop experienced a thousand difficulties in crossing the plains from which the Hakarimata Ranges arise. But they reached the banks of the Waipa before noon, and from there had no troubles following the river northward.

It was a charming valley, crossed with many small creeks of fresh, pure water which ran happily under the shrubs. According to the botanist Hooker, two thousand new species of plants have been discovered in New Zealand, of which five hundred were first described by him. The flowers are rare, of subdued colouring, and annual plants are scarce, but there are plenty of Filicophyta, grasses, and Apiaceae.

Some tall trees rose here and there out of the undergrowth of dark greenery, Metrosideros with scarlet flowers, Norfolk pines, Thujas with vertically compressed twigs, and the rimu, which resembled the sad European cypress trees. All these trunks were surrounded by many varieties of ferns. Birds fluttered and chatted between the branches of the tall trees, on the tops of the shrubs: cockatoos; green kākāriki, with a red band under its throat; the taupo, adorned with a fine pair of black whiskers; and the kaka, a parrot as large as a duck, with bright red plumage on the undersides of its wings, which naturalists have dubbed the Nestor meridionalis.

The Major and Robert were able, without leaving the group, to shoot some snipe and partridge, which were resting under the low forest of the plains. Olbinett, in order to save time, took care of plucking them while he walked.

Paganel, for his part, was less sensitive to the nutritional qualities of the game. He would have liked to catch some particular species of bird in New Zealand. The curiosity of the naturalist overcame the appetite of the traveller. His memory, if it did not deceive him, reminded him of the strange ways of the tui of the natives, sometimes called a “mockingbird” for its ceaseless cackling and sometimes “parson bird” because it has a white collar at the neck of its black cassock-like plumage.

“This bird,” Paganel told the Major, “becomes so fat during the winter that he becomes ill. He can not fly anymore. Then, he tears his chest with pecks, in order to get rid of his fat and make himself lighter. Does not this seem strange to you, MacNabbs?”

“So strange,” said the Major, “that I do not believe a word of it!”

Paganel, to his great regret, could not find a single example of these birds, to show the incredulous Major the bloody scarifications of their breasts.1

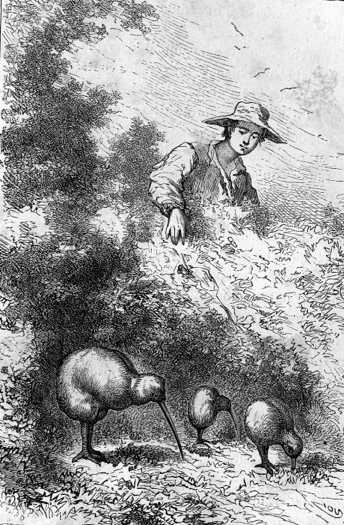

But he was happier with a strange animal, which — under the pursuit of man, cat, and dog — fled to the uninhabited country and is quickly disappearing from the fauna of New Zealand. Robert, searching like a ferret, discovered a pair of wingless and tailless hens in a nest formed of intertwined roots. They had four toes on their feet, a long woodcock beak and white hairy feathers all over their bodies. Strange animals, which seemed to mark a transition from oviparous to mammalian animals.

The New Zealand kiwi

It was the New Zealand kiwi, Apteryx australis to naturalists, which feeds indiscriminately on larvae, insects, worms, and seeds. This bird is unique to the country. It has barely been introduced into the zoos of Europe. Its half-drawn form, its comic movement, have always attracted the attention of travellers, and during the great exploration in Oceania of the Astrolabe and the Zealous, Dumont D’Urville was mainly charged by the Academy of Sciences to bring back a specimen of these singular birds. But, despite the rewards promised to the natives, he could not procure a single living kiwi.

Paganel, happy with such a good fortune, tied together his two hens and carried them off bravely with the intention of paying homage to the Jardin des Plantes of Paris. In his mind’s eye, the confident geographer already pictured the seductive inscription “Given by M. Jacques Paganel,” on the most beautiful cage of the establishment!

The little troop descended the course of the Waipa without difficulty. The country was deserted, there was no trace of natives, no paths indicating the presence of man in these plains. The waters of the river flowed between high bushes or glided down gentle slopes. Their eyes wandered over the small mountains that bordered the valley in the east. With their strange shapes, their profiles drowned in a deceptive mist, they looked like gigantic animals, worthy of antediluvian times. They could have been a whole herd of enormous cetaceans, caught by a sudden petrification. Their tormented masses emanated an essentially volcanic character. New Zealand is the recent product of a plutonian work. Its emergence from the waters is constantly ongoing. Some places have risen by a fathom in the past twenty years. Fire still runs through her bowels, shakes her, convulses her, and escapes through the mouths of many geysers and the craters of volcanoes.

At four o’clock in the afternoon, they had happily covered nine miles. According to Paganel’s map, they were within five miles of the confluence of the Waipa and the Waikato, where they would meet the road to Auckland. They could camp there for the night. Two or three days would be enough to cover the remaining fifty miles which separated them from the capital. If Glenarvan met the postal carriage, which provides a bi-monthly service between Auckland and Hawke’s Bay, it could be done in as little as eight hours.

“So,” said Glenarvan, “we will still be forced to camp next night?”

“Yes,” said Paganel, “but for the last time, I hope.”

“Good, because this is very hard for Lady Helena and Mary Grant.”

“And they endure it without complaint,” said John Mangles. “But, if I’m not mistaken, Mr. Paganel, you mentioned a village at the meeting of the two rivers?”

“Yes,” said the geographer. “Here it is marked on Johnston’s map. It is Ngaruawahia, about two miles below the confluence.”

“Well, could not we stay there for the night? Lady Helena and Miss Grant would not hesitate to go two miles more to find a suitable hotel.”

“Hotel?” cried Paganel. “A hotel in a Māori village! You won’t even find an inn or a cabaret! This village is only a group of native huts, and far from seeking asylum there, I think we would be well advised to avoid it.”

“Always your fears, Paganel!” said Glenarvan.

“My dear Lord, it is better to distrust than trust the Māori. I do not know their relationship with the English: if the insurrection is suppressed, or victorious, or if we will land in the middle of the war. But modesty aside, people of our quality would be a good catch, and I do not wish to experience the hospitality of the Māori. So I think it’s wise to avoid the village of Ngaruawahia, to turn away from it, to flee any meeting with the natives. Once in Drury, it will be different, and there, our valiant companions can recover at their ease from the trials of the journey.”

The opinion of the geographer prevailed. Lady Helena preferred to spend one last night in the open air rather than expose her companions to danger. Neither she, nor Mary Grant asked to stop, and they continued to follow the banks of the river.

Two hours later, the first shadows of evening began to descend from the mountains. Before disappearing under the horizon in the west, the sun had darted some late rays through a sudden gap in the clouds. The distant summits to the east were reddened by the last fires of the day, like a parting salute to the weary travellers.

Glenarvan and his people hurried on. They knew the brevity of the twilight in this already elevated latitude, and how quickly the darkness of night came on. They wanted to reach the junction of the two rivers before deep darkness. But a thick fog rose from the ground, and made seeing their way very difficult.

Fortunately, hearing replaced sight, which the darkness had rendered useless. Soon a more accentuated murmur of the waters indicated the meeting of the two rivers in the same bed. At eight o’clock, the little troop arrived at the point where the waters of the Waipa merged into the Waikato, with a roaring turbulence of waves.

“The Waikato is here,” said Paganel, “and the Auckland road goes up along its right bank.”

“We will see it tomorrow,” said the Major. “Let’s camp here. It seems to me that those dark shadows over there are a small thicket of trees which might as well have been put there expressly to shelter us. Supper and sleep.”

“Supper,” said Paganel. “But biscuits and dry meat, without lighting a fire. We have arrived here incognito. Let us try to remain so! Fortunately, this fog makes us invisible.”

They reached the thicket of trees, and everyone conformed to the wishes of the geographer. They ate their cold supper quietly, and soon a deep sleep fell upon the travellers, tired by a march of fifteen miles.

1. And if he had, the Major’s scepticism of this story about the tui would have been confirmed.