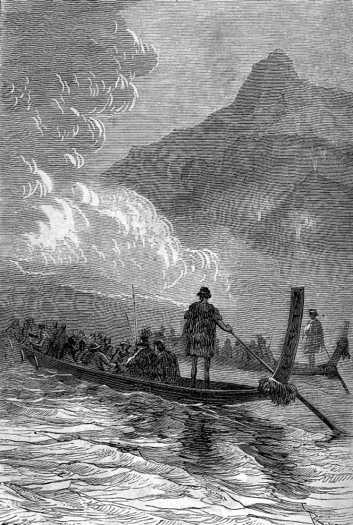

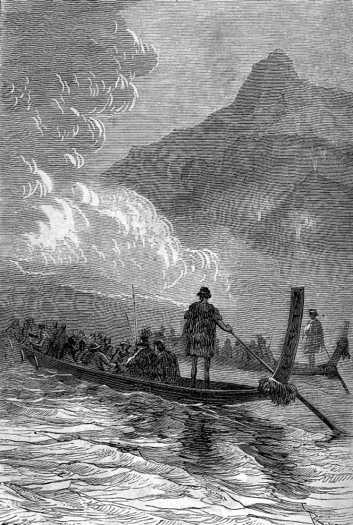

It was a canoe, seventy feet long

The next day, at dawn, a dense mist crept heavily on the waters of the river. Some of the vapour which saturated the air had condensed over the cool water, and covered the surface with a thick fog. But the rays of the sun soon pierced these banks of mist, and they melted away under the gaze of the radiant star. The riversides emerged from the haze, and the course of the Waikato appeared in all its morning beauty.

A finely elongated tongue of land, bristling with shrubs, came to an end in a point at the meeting of the two currents. The more chaotic waters of the Waipa drove a quarter of a mile into the waters of the Waikato before they became confused; but that river, powerful and calm, soon checked the angry waters, and dragged them peacefully along its course to the Pacific Ocean.

It was a canoe, seventy feet long

When the vapours rose, a boat appeared, going up the current of the Waikato. It was a canoe, seventy feet long, five broad, three deep, the front raised like a Venetian gondola, and it was carved entirely from a single trunk of a kahikatea fir. A bed of dry fern covered the bottom. Eight paddlers at the front made it fly on the surface of the water, while a man, seated at the stern, directed it by means of a steering oar.

This man was a tall native, about forty-five years old, with broad chest, and muscular arms and legs. His bulging forehead, furrowed with thick creases, violent expression, and sinister countenance, gave him a formidable appearance.

He was a high ranking Māori leader. This could be seen in the thin, tight tattooing that streaked his body and face. Two black spirals swept out like wings from his aquiline nose to encircle his yellow eyes, and meet on his forehead, where they disappeared into his magnificent hair. He had bright teeth, and his chin disappeared under a pattern of elegant scrolls that continued down to his sturdy chest.

The tattoo, the moko of the New Zealanders, is a mark of high distinction. Only a man who has participated valiantly in battle was worthy of these honorary sigils. Slaves, and people of the lower classes, can not claim them. Famous leaders identify themselves by the finesse, precision, and nature of their designs, which often cover their entire bodies with images of animals. Some undergo the very painful operation of receiving moko up to five times. The more illustrious you are, the more you are “illustrated” in New Zealand.

Dumont D’Urville gave interesting details of this custom. He pointed out that the moko was like the coats of arms that some families are so proud of in Europe. But he noted an important difference between these two signs of distinction. The coats of arms of Europeans often only attested to the individual merit of the person who first obtained them, without saying anything about the merit of his children, while the individual moko of the Māori genuinely testify that the bearer had shown extraordinary personal courage in order to have the right to wear them.

In addition, the tattooing of the Māori, independent of the consideration which the bearer enjoys, has an incontestable utility. It toughens the skin, which allows it to withstand the weather of the seasons, and incessant mosquito bites.

As for the leader who directed this boat, there was no doubt about his distinction. The sharp albatross bone, which is used by Māori tattooers, had furrowed his face five times in close and deep lines. His moko was in its fifth edition, and it showed in his haughty look.

He was wearing a loincloth, still bloody from recent battles, and draped in a large cloak of Phormium trimmed with dog pelts. Green jade dangled from his elongated earlobes, and his neck was encompassed with necklaces from which dangled pounamu, the highly treasured sacred stones of the Māori. At his side lay an English rifle, and a patiti, a kind of tomahawk, emerald coloured and eighteen inches long.

Beside him, nine warriors of lesser rank remained perfectly immobile, wrapped in their Phormium mantles. All were armed, with a fierce bearing, and some still suffered from recent wounds. Three wild-looking dogs were lying at their feet. The eight paddlers at the front seemed to be servants or slaves to the leader. They paddled vigorously. The boat was moving against the slow current of Waikato at a considerable speed.

In the centre of this long boat, with their feet tied, but their hands free, ten European prisoners were packed tightly together.

They were Lord Glenarvan and Lady Helena, Mary and Robert Grant, Paganel, the Major, John Mangles, the steward, and the two sailors.

The evening before, all the little troop — deceived by the thick fog — had gone to camp in the midst of a numerous party of natives. Toward the middle of the night, the travellers, caught in their sleep, were taken prisoner and taken aboard the canoe. They had not been mistreated so far, but they had tried in vain to resist. Their arms and ammunition were in the hands of the savages, and they would have been shot with their own guns.

It was not long before they learned, by overhearing some English words used by the natives, that the latter, driven back by British troops, beaten and decimated, were returning to the of Upper Waikato district. The Māori chief, after a stubborn resistance, his main warriors killed by soldiers of the 42nd Regiment, returned to make a new appeal to the tribes of the river to go to the aid of the indomitable William Thompson, who was still struggling against the conquerors. This chief was named Kai-Kúmu, a sinister name in the native language, which means “he who eats the arms of his enemy.” He was brave and daring, but his cruelty equaled his valour. They could expect no mercy from him. His name was well known to the English soldiers, and the governor of New Zealand had placed a price on his head.

This terrible blow had struck Lord Glenarvan just as he was about to reach the desired Auckland Harbour and repatriate to Europe. But by looking at his his cold, calm face, one could not have guessed the depth of his anxiety. This was because Glenarvan always rose to meet any challenge that misfortune dealt him. He felt that he must be strong, to set an example, for his wife and his companions. He, as the husband and leader was ready to die first for the common salvation if circumstances should require it. Deeply religious, he never lost his faith in God’s justice, nor his belief in the sanctity of his undertaking. In the midst of the perils accumulated on this journey, he did not regret the generous impulse which had carried him into the country of these savages.

His companions were worthy of him; they shared his noble thoughts, and to see their tranquil and proud countenances you would not have thought they had been led into a supreme catastrophe. Besides, by mutual agreement and on the advice of Glenarvan, they had resolved to affect a superb indifference to the natives. It was the only way to impress their wild natures. Savages, in general, and particularly the Māori, have a certain sense of dignity from which they never depart. They respect coolness and courage. Glenarvan knew that by remaining calm and composed, he spared himself and his companions from unnecessary mistreatment.

Since leaving the camp, the natives — not very talkative, like all savages — had scarcely spoken to each other. But from the few words exchanged, Glenarvan recognized that the English language was familiar to them. He decided to question the Māori chief as to the fate reserved for them.

He addressed Kai-Kúmu calmly, his voice free of fear. “Where are you taking us, chief?”

Kai-Kúmu looked at him coldly without answering him.

“What do you plan to do with us?” continued Glenarvan.

Kai-Kúmu’s eyes flashed briefly, and in a deep voice he replied “To exchange you, if your people want you; to kill you, if they refuse.”

Glenarvan did not ask for more, but hope returned to his heart. No doubt some of the Māori leaders had fallen into the hands of the English, and the natives wanted to try to recover them through a prisoner exchange. There was a chance of salvation; the situation was not hopeless.

The canoe was moving rapidly up the river. Paganel, whose mercurial nature easily swung from one extreme to the other, had recovered all his hope. He told himself that if the Māori saved them the trouble of walking to the English outposts, that it was so much the better. So, resigned to his fate, he followed the course of the Waikato across the plains and valleys of the province on his map. Lady Helena and Mary Grant, hiding their terror, conversed in low voices with Glenarvan, and the most skilful physiognomist would not have read the anguish of their hearts on their faces.

The Waikato is the national river of New Zealand. The Māori are proud and jealous of it, like the Germans of the Rhine, and the Slavs of the Danube. In its two hundred mile course, it watered the most beautiful regions of the northern island, from the province of Wellington to the province of Auckland. It gave its name to all those riverside tribes who, indomitable and untamed, rose en masse against the invaders.

The waters of this river are still almost untouched by any stranger. They opened only in front of the bows of the islander canoes. Hardly any audacious tourists had ventured between these sacred shores. Access to the headwaters of the Waikato seems to be forbidden to the European laymen.

Paganel knew the veneration of the natives for this great New Zealand artery. He knew that English and German naturalists had scarcely explored it beyond its junction with the Waipa. How far would Kai-Kúmu’s pleasure take his captives? He would not have guessed it if the word “Taupo”, frequently repeated between the chief and his warriors, had not arrested his attention.

He looked at his map and saw that the name of Taupo applied to a lake famous in geographical records, located in the mountainous heart of the island, to the south of the province of Auckland. The Waikato passes through this lake. From the Waipa confluence to the lake, the river’s course was about one hundred and twenty miles.1

Paganel, addressing John Mangles in French so as not to be understood by the savages, asked him to estimate the speed of the boat. John told him it was about three miles an hour.

“Then,” said the geographer, “if we stop at night, our journey to the lake will take nearly four days.”

“But where are the English outposts located?” asked Glenarvan.

“It is difficult to say,” said Paganel. “But, the war has to have moved into the province of Taranaki, and, in all probability, the troops are massed on that side of the lake, behind the mountains, which have been the focus of the insurrection.”

“God grant it!” said Lady Helena.

Glenarvan glanced sadly at his young wife, at Mary Grant, exposed to the mercy of these savage natives and carried away to a wild country far from any human intervention. But he saw himself observed by Kai-Kúmu, and, out of prudence, not wishing to let him guess that one of the captives was his wife, he turned his thoughts inward and observed the banks of the river with perfect indifference.

The boat had passed in front of the old residence of King Potatau without stopping, half a mile above the confluence. No other boat was plying the waters of the river. Some huts, widely spaced on the banks, testified by their disrepair to the horrors of the recent war. The riparian countryside seemed abandoned, the banks of the river were deserted. Some representatives of the family of waterfowl alone animated this sad loneliness. Sometimes a pied stilt — a wading bird with black wings, a white belly, and a red beak — fled on his long legs. Sometimes, herons of three species: the grey matuku; a kind of stupid-looking bittern; and the magnificent kotuku with white plumage, yellow bill, and black feet; peacefully watched the native boat pass. Where the sloping banks showed enough depth to the water, the kingfishers, the kōtare in Māori, watched for the small eels that wriggle by the millions in the rivers of New Zealand. Where the bushes were overhanging the river, proud hoopoes, rallecs, and sultana hens had their morning baths under the first rays of the sun. All the winged world enjoyed in peace the leisure created by the absence of men, expelled or decimated by the war.

During this first part of its course, the Waikato flowed through wide, vast plains. But upstream the hills, then the mountains, were going to narrow the valley through which its bed had been dug. Ten miles above the Waipa, Paganel’s map indicated the village of Kirikiriroa on the west bank, which was indeed there. Kai-Kúmu did not stop. He had the prisoners given their own food, which had been taken in the looting of the camp. His warriors, his slaves, and he were satisfied with the native food, edible ferns, the Pteridium esculentum to botanists, baked roots, and kapanas, potatoes, which grew abundantly in the two islands. No animal matter appeared in their meals, and the dried meat of the captives did not seem to inspire them with any desire.

At three o’clock, a few mountains rose on the east bank, the Pokaroa Ranges, which looked like a demolished curtain wall. Ruined pās, ancient entrenchments erected by Māori engineers in impregnable positions were perched on rocky ridges. They looked like giant eagles’ nests.

The sun was about to set below the horizon when the canoe landed on a bank covered with pumice stones which the Waikato draws down its course from the volcanic mountains. A few trees grew there which appeared to be suitable for sheltering a camp. Kai-Kúmu disembarked his prisoners, and the men had their hands tied. The women remained free. All were placed at the centre of the encampment, surrounded by fires which made an unbroken circle of light around them.

Before Kai-Kúmu had told his captives that he intended to exchange them, Glenarvan and John Mangles had discussed ways to regain their freedom. While no possibilities had presented themselves in the canoe, they had hoped to find an opportunity in the night, once they landed and made camp.

But since Glenarvan had talked with the Māori chief, it seemed wise to abstain. It was the most prudent course to wait. A prisoner exchange offered a chance at salvation that did not involve an armed conflict, or a flight through these unknown lands. Many events might arise which would delay or prevent such a negotiation, but for now it was best to wait for that outcome. Indeed, what could ten unarmed men do against thirty well-armed savages? Glenarvan, moreover, supposed that Kai-Kúmu’s tribe had lost some chief of high value which he particularly wished to get back, and he was not mistaken.

The next day the boat ascended the course of the river with new speed. At ten o’clock they stopped for a moment at the confluence of the Pokaiwhenua, a small river which meandered over the plains of the east bank.

A canoe, manned by ten natives, joined Kai-Kúmu’s boat. The warriors barely exchanged the arrival greeting, “aire mai ra,” which means “come well,” before the two canoes continued together. The newcomers had recently fought against English troops. It was seen in their ragged clothes, their bloody arms, the wounds still bleeding under their rags. They were dark, and taciturn. With the natural indifference of all savage peoples, they paid no attention to the Europeans.

At noon, the summit of Maungatautari appeared in the west. The Waikato Valley was beginning to narrow. The river, tightly constrained, became powerful rapids. But the strength of the natives, doubled and regularized by a song which punctuated the beating of their paddles, pushed the boat over the foaming waters. The rapids were overcome, and the Waikato resumed its slow course, only varied from mile to mile by the winding of its banks.

Toward evening, Kai-Kúmu landed at the foot of mountains whose first buttresses fell steeply to the narrow banks. There, about twenty natives disembarked from their canoes to make arrangements for the night. Fires were set blazing under the trees. A chief, equal to Kai-Kúmu, advanced with measured steps, and, pressing his nose against Kai-Kúmu’s, gave him the cordial greeting of the hongi. The prisoners were placed in the centre of the camp and guarded with extreme vigilance.

The next morning, this long voyage up the Waikato was resumed. Other boats joined them, coming from the small tributaries of the river. About sixty warriors were now assembled, fugitives from the latest battles of the insurrection, returning to the mountains. Many suffered from greater or lesser wounds from English bullets. Sometimes a song rose from the line of canoes. A native sang the patriotic ode of the mysterious Pihe

“Pápa ra te wáti tídi

I dúnga nei”

the national anthem that inspires the Māori in their war of independence.2 The voice of the singer, full and sonorous, echoed off the mountains, and after each verse, the natives would strike their chests, which resounded like a drum, and joined the bellicose verse in chorus. Then, with renewed strength from the paddlers, the canoes made way against the current and flew over the surface of the waters.

A curious phenomenon marked this day of navigation on the river. About four o’clock, the canoe, without hesitation or delaying its course, guided by the firm hand of the chief, threw itself through a narrow valley. The swirling current raged against numerous islets which made this section of the river especially dangerous. But to capsize here was particularly undesirable, because the shore offered no refuge. Anyone who stepped on the boiling mud of the banks would surely have died.

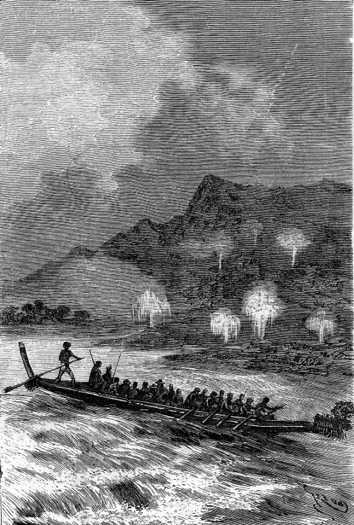

The river flowed between hot springs

The river flowed between hot springs, which have always been known as a curiosity to tourists. Iron oxide coloured the ooze of the banks bright red where a solid foothold of tufa had not built up. The atmosphere was saturated with a penetrating sulphurous odour. The natives did not appear affected, but the captives were seriously inconvenienced by the miasmas issuing from the fissures in the ground, and the bubbles which burst under pressure from internal gases. But if it was unpleasant to smell these emanations, the eye could only admire this imposing spectacle.

The boats ventured into the depths of a cloud of white vapour. Its dazzling spirals rose over the river. On its banks, about a hundred geysers, some throwing clouds of vapour, others pouring out columns of liquid, varied their displays like the jets and cascades of a fountain designed by the hand of man. It seemed as if some conductor was directing the intermittent play of these springs for his pleasure. Water and vapour, merged in the air, were excited by the rays of the sun.

In this place, the Waikato was flowing on a moving bed which was constantly boiling under the action of underground fire. Not far from Lake Rotorua, to the east, roared the hot springs and steaming waterfalls of Lake Rotomahana and Mount Tarawera, which have been seen by some bold travellers. This region is pierced with geysers, craters, and solfataras. They provide another outlet for the overflow of gases that could not find an outlet in the insufficient valves of Mounts Tongariro and Wakaari, the only active volcanoes of New Zealand.3

The native canoes sailed under this vault of vapour for two miles, enveloped in the warm spirals which rolled on the surface of the waters. Then, the sulphurous smoke dissipated, and pure air, drawn by the rapidity of the current, came to refresh the panting breasts. They had passed beyond the hot springs.

Before the end of the day, the Hipapatua and Tamatea rapids were ascended under the vigorous paddling of the savages. In the evening, Kai-Kúmu camped a hundred miles from the confluence of Waipa and Waikato. From here, their course up the Waikato would first turn to the east, before swinging back to the south, where the outflow from Lake Taupo fell into it.

At noon, the boats reached Lake Taupo

The next day, Jacques Paganel, consulting the map, identified Mount Tauhara on the east bank, which rises over three thousand feet above sea level.

At noon, the whole procession of boats came to a widening of the river, and paddled into Lake Taupo. The natives saluted a flap of cloth which fluttered in the wind at the top of a hut. It was the Māori flag.

1. 50 leagues, 200 kilometres — DAS

2. The line quoted from the song translates as “The thunder above, bursts forth.”a

The pihe is a Māori funeral ode, often sung to mourn the losses from a battle, not a national anthem. The idea that this particular pihe is an anthem seems to have originated with Dumont d’Urville, from his study of the Māori in 1827.b

a. Williams, William. A Dictionary of the New Zealand Language and a Concise Grammar; to Which Is Added a Selection of Colloquial Sentences. London: Williams and Norgate, 1852. pg 110

b. McLean, Mervyn. Māori Music. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1996, pg 71

3. New Zealand has many active volcanoes. Indeed, one of the largest eruptions in recorded New Zealand history took place at Mount Tarawera, in 1886.