Salt springs of strange transparency

It was necessary to take full advantage of the night to to get as far as possible from the fatal area of Lake Taupo. Paganel took the lead of the little troop, and his marvellous traveller’s instinct was revealed again during this difficult journey into the mountains. He maneuvered with surprising skill through the the darkness, choosing almost invisible paths without hesitation, not deviating from his chosen direction. His nyctalopia served him well, and his cat-like eyes allowed him to distinguish the smallest objects in the profound darkness.

They walked for three hours, without stopping, along the broad flanks of the eastern ranges. Paganel inclined their route a little to the southeast, in order to reach the narrow pass between the Kaimanawa and the Huiarau Ranges used by the road from Auckland to Hawke’s Bay. Once through this gorge, he intended to leave the road and, sheltered by the high mountain chains, march to the coast through the uninhabited regions of the province.

By nine o’clock in the morning, they had covered twelve miles in twelve hours. No more could be demanded of the courageous women. Besides, they had reached a good place to camp. The fugitives had reached the pass separating the two chains. The overland road remained to their right and ran south. Paganel, his map in his hand, made a hook to the northeast, and at ten o’clock the little troop reached a natural redan formed by a projection of the mountains. Some of their provisions were taken from the sacks, and they were thankfully consumed. Mary Grant and the Major, who had not cared for the edible fern until then, enjoyed it that day. They rested until two o’clock in the afternoon before they continued eastward. In the evening the travellers were eight miles from the mountains when they stopped. No one objected to sleeping in the open air.

The route became more difficult the next day. It was necessary to cross a curious district of volcanic lakes, geysers and solfataras which extends to the east of the Huiarau Ranges. It was much more delightful to the eyes, than to the legs. Every quarter of a mile there were detours, obstacles, and false trails. It was exhausting, but what a strange spectacle, and what an infinite variety of scenery nature provided!

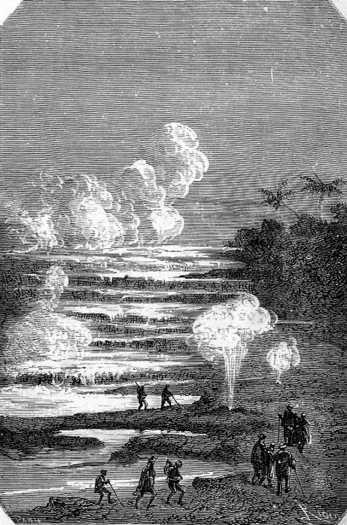

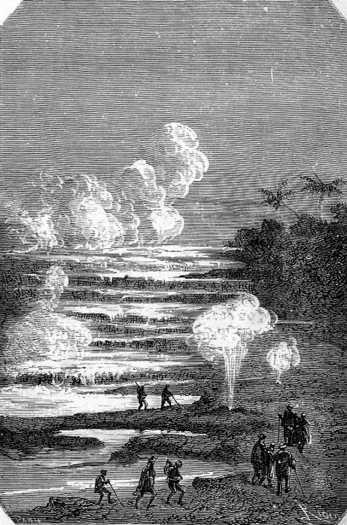

Salt springs of strange transparency

In this vast area of twenty square miles, the effusions of the subterranean forces took place in all their forms. Salt springs of strange transparency, populated by myriads of insects, emerged from the copses of native tea trees. They gave off a penetrating odour of burned powder, and deposited a white residue like dazzling snow on the ground. Their limpid waters were nearly boiling, while other nearby springs flowed in icy sheets. Gigantic ferns grew on their banks, under conditions analogous to those of the Silurian age.

Liquid sheaves, enveloped in vapour, darted from the ground like the fountains of a park on all sides. Some were continuous, others intermittent and subject to the pleasure of a capricious Pluto. They were arranged in amphitheatres of natural terraces layered in a cascade of shallow basins. Their waters were gradually confused beneath the spirals of white steam, and eroding the diaphanous steps of these gigantic staircases, they fed entire lakes with their bubbling waterfalls. Farther on, the hot springs and the tumultuous geysers were succeeded by the solfataras. There were so many half eroded craters, cracked with numerous fissures from which various gases were emerging, that the ground appeared covered with large pustules. The atmosphere was saturated with the pungent and unpleasant odour of sulphurous acids. Crusts and crystalline concretions of sulphur carpeted the ground. Incalculable sterile riches had accumulated for centuries, and it is to this little known district of New Zealand that industry will come to supply itself, if the soufrières of Sicily are exhausted one day.

It is easy to understand how exhausting it was for the travellers to cross these regions bristling with obstacles. Suitable campsites were difficult to find, and the hunters’ rifles did not meet a bird worthy of being plucked by Mr. Olbinett. It was most often necessary to be content with ferns and sweet potatoes, a meagre meal which did not recoup the exhausted strength of the little troop. Everyone was eager to leave these arid and deserted lands.

It took no less than four days to cross this impracticable country. On the 23rd of February, only fifty miles from Maunganamu, Glenarvan camped at the foot of an unnamed mountain marked on Paganel’s map. Plains of shrubs stretched before him, and the great forests reappeared on the horizon.

This was a good omen, provided that the habitability of these regions didn’t bring back too many inhabitants. So far, the travellers had not seen the shadow of a Māori.

MacNabbs and Robert had killed three kiwis that day, which figured with honour on the camp table, but not for long, to tell the truth, because in a few minutes they were devoured from beaks to feet.

Then at dessert, between potatoes and sweet potatoes, Paganel made a motion that was adopted with enthusiasm.

He proposed to give the name “Glenarvan” to the unnamed mountain which rose three thousand feet into the clouds, and he carefully printed the name of the Scottish lord onto his map.

To recount all the rather monotonous and uninteresting events which marked the rest of the journey would be pointless. Only two or three incidents of some importance marked this crossing of the island from the lakes to the Pacific Ocean.

They walked all day through forests and plains. John took sightings of the sun and the stars. The weather was rather mild, sparing its heat and its rains. Nevertheless, increasing exhaustion was slowing these travellers who had been so cruelly tried, and they were eager to reach the missions at the coast. They were still chatting, but not all together. The little troop was divided into groups which formed, not by close sympathy, but a communion of more personal ideas.

Most often Glenarvan walked by himself, thinking of the Duncan and her crew as he approached the coast. He forgot the dangers that still threatened him en-route to Auckland, to think of his slain sailors. The horrible image would not leave him.

They did not talk about Harry Grant anymore. What good was it, since nothing could be done for him? If the name of the captain was still mentioned, it was in the conversations between his daughter and John Mangles.

John had not reminded Mary of what she had told him during the last night in the Ware Atua. His discretion did not allow him to take advantage of a word uttered in a moment of supreme despair.

When he talked about Harry Grant, John always talked of continuing the search. He told Mary that Lord Glenarvan would resume this aborted endeavour. He started from the position that the authenticity of the document could not be doubted, so Harry Grant was alive somewhere. If they had to search the whole world, they would find him. Mary was entranced by these words, and she and John, united by the same thoughts, were now joined in the same hope. Lady Helena often took part in their conversations, but she did not lose herself to so many illusions. And yet, she did not bring these young people back to sad reality.

Meanwhile, MacNabbs, Robert, Wilson, and Mulrady hunted without straying far from the little troop, and each of them supplied his share of game. Paganel, still draped in his Phormium cloak, kept aloof, quiet and thoughtful.

And yet, it is good to say, in spite of the law of nature which states that in the midst of trials, danger, exhaustion, and privation, the best of characters may be wrinkled and soured, all these companions in misfortune remained united, devoted, and ready to die for each other.

On February 25th, the route was blocked by a river that was marked on Paganel’s map as the Waikare. They crossed it.

Plains of scrub succeeded one another for two uninterrupted days. Half the distance between Lake Taupo and the coast had been crossed without an accident, if not without fatigue.

They came to immense and endless woodlands, reminiscent of the Australian forests; but here, kauris replaced eucalyptus. Despite the preceding four months of incredible sights, Glenarvan and his companions were still amazed by these gigantic pines, worthy rivals of the cedars of Lebanon, and the mammoth trees of California. These kauris — Agathis australis to a botanist — grew to one hundred feet in height before branching. They grew in isolated clusters, and the forest was composed not of trees, but of innumerable clumps of trees, which extended their parasol of green leaves to two hundred feet in the air.

Some of these pines, still young — scarcely a hundred years old — resembled the red firs of Europe. They carried a dark green crown topped by a sharp cone. On the other hand, their elders — trees five or six centuries old — formed immense tents of greenery supported on an inextricable latticework of branches. These patriarchs of the New Zealand forest measured up to fifty feet in circumference, and the united arms of all the travellers could not encircle their trunks.

For three days the little troop ventured under these vast arches on a clay soil that no man’s foot had ever trod. It was easy to see in the heaps of resinous gum piled up in many places at the foot of the kauris, which would have supported many years of native exploitation.1

The hunters found many coveys of kiwis, so rare in the middle parts of the island frequented by the Māori. It is in these inaccessible forests that these curious birds have taken refuge from being hunted by the New Zealand dogs. They provided an abundant and healthy food for the meals of the travellers.

It even happened that Paganel saw a couple of gigantic birds in a thicket in the distance. His naturalist’s instinct was revived. He called his companions, and, in spite of their exhaustion, the Major, Robert, and he, hurled themselves on the tracks of these animals.

The ardent curiosity of the geographer could be understood, for he had recognized — or believed he recognized — these birds to be “moas,” belonging to the genus of Dinornis, which several scholars rank among the extinct varieties. But this meeting confirmed the opinion of Dr. von Hochstetter, and other explorers, that these wingless giants of New Zealand still existed.2

The moas pursued by Paganel, these contemporaries of the megatheriums and pterodactyls,3 were up to eighteen feet in height. They were oversized and easily frightened ostriches, that fled with extreme speed. Not even a rifle bullet could stop them in their flight! After a few minutes of chase, these elusive moas disappeared behind some large trees, and the hunters gained nothing for their pains, or expense of powder.

That evening, on the 1st of March, Glenarvan and his companions finally abandoned the immense forest of kauris, and encamped at the foot of Mount Hikurangi, whose summit rose 5,500 feet in the air.

Nearly a hundred and forty miles had been travelled since they left Maunganamu, and the coast was still thirty miles away. John Mangles thought that they had made excellent time,4 in spite of the difficulties of this region.

The detours, the obstacles of the road, and the imperfections of their bearings, had lengthened it by a fifth, and unfortunately the travellers who arrived at Mount Hikurangi were completely exhausted.

It would take two more long days of walking to reach the coast. An extreme vigilance, unnecessary for many days, became necessary again, for they were returning to a country often frequented by the Māori.

However, everyone tamed their weariness, and the next day the little troop set out at daybreak.

Between Mount Hikurangi, which they passed to their right, and Mount Hardy, the summit of which rose to a height of 3,700 feet on their left, the journey became very painful. For ten miles the plain bristled with “supplejack,” a sort of flexible creeper aptly named “choking vines.” Arms and legs were entangled at every step, and these lianas, veritable serpents, wound the body in their tortuous coils. For two days it was necessary to advance with an axe in hand, and to fight against a hydra with a hundred thousand heads. Paganel would have gladly classified these troubling and tenacious plants among the zoophytes.

Hunting became impossible in these plains, and the hunters no longer brought their accustomed tribute. They reached the end of their provisions; they could not be renewed. There was no water; they could not quell their thirsts, doubled by fatigue.

The sufferings of Glenarvan and his people were horrible, and for the first time their morale was about to abandon them.

Finally, no longer walking, but dragging themselves along, soulless bodies only led by the instinct for survival that outlasted any other feeling, they reached Point Lottin, on the shores of the Pacific.

They found some deserted huts — the ruins of a village recently devastated by the war — abandoned fields, everywhere marks of plunder and fire. Destiny had reserved a new and terrible trial for the unfortunate travellers.

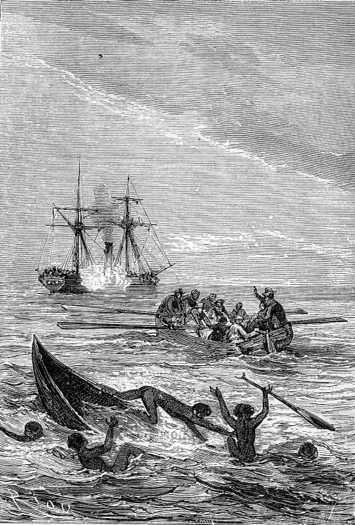

They were wandering along the shore when a detachment of natives appeared a mile from the coast. The natives rushed toward them, waving their weapons. Glenarvan, his back to the sea, could not escape, and, drawing his last strength, he was prepared to fight, when John Mangles exclaimed “A boat, a boat!”

Twenty paces away, indeed, a boat with six oars was stranded on the beach. To launch it, to jump into it and to flee this dangerous shore, took only a moment. John Mangles, MacNabbs, Wilson, and Mulrady took to the oars; Glenarvan took the rudder; the two women, Olbinett, and Robert lay beside him.

In ten minutes the boat was a quarter mile off the shore. The sea was calm. The fugitives kept a profound silence.

John, not wishing to deviate too far from the coast, was about to follow the shore, when his oar suddenly stopped in his hands.

He had just caught sight of three canoes coming out of Point Lottin, with the evident intention of chasing them.

“Out to sea! Out to sea!” he yelled. “It would be better to perish in the waves!”

The boat, propelled by its four oars, turned out to sea. For half an hour they were able to maintain their distance; but the poor exhausted rowers were beginning to falter, and the three canoes were noticeably gaining on them. Scarcely two miles now separated them. There was no possibility of avoiding an attack from the natives, who were preparing their rifles to fire.

What was Glenarvan to do? Standing at the back of the boat, he looked for some chimerical help on the horizon. What did he hope for? What could he expect? Did he have a premonition? Suddenly, his gaze caught fire, his hand extended to a point on the horizon.

“A ship!” he cried. “My friends, a ship! Row! Row hard!”

Not one of the four rowers turned to see this unexpected ship, because one should not lose a stroke of an oar. Only Paganel, getting up, pointed his telescope at the point indicated.

“Yes!” he said. “A ship! A steamer! She’s at full steam! She’s coming to us! Row hardy, my comrades!”

The fugitives found a new energy, and for half an hour they maintained their distance with strong strokes of their oars. The steamer became more and more visible. They could see her two masts, empty of canvas, and big billows of her black smoke. Glenarvan, abandoning the tiller to Robert, had seized the geographer’s telescope and was tracking all of the ship’s movements.

But what did John Mangles and his companions think when they saw the Lord’s features contract, his face turn pale, and the instrument fall from his hands? A single word explained this sudden despair to them.

“The Duncan!” cried Glenarvan. “The Duncan, and the convicts!”

“The Duncan?” cried John, who dropped his oar and got up immediately.

“Yes! Death on both sides!” murmured Glenarvan, broken by so much anguish.

It was indeed the yacht; they could not be mistaken. The yacht with its crew of bandits! The Major could not restrain a curse he threw against the sky. It was too much!

The boat was allowed to drift. Which way to go? Where to flee? Was it possible to choose between savages or convicts?

A gun fired from the nearest native boat, and the bullet struck Wilson’s oar. A few strokes of the oars then pushed the boat toward the Duncan.

The yacht was steaming only half a mile away. John Mangles, cut off on all sides, did not know where to turn, in which direction to flee. The two poor women, kneeling, desperate, prayed.

The savages fired a volley, and bullets rained around the canoe. A loud detonation broke out, and a cannonball, launched by the gun of the yacht, passed over the heads of the fugitives. The latter, caught between two fires, remained motionless between the Duncan and the native canoes.

John Mangles, mad with despair, seized his axe. He was about to scuttle the boat, to submerge it with his unfortunate companions, when a cry from Robert stopped him.

“Tom Austin! Tom Austin!” yelled the child. “He’s on board! I see him! He’s recognized us! He’s waving his hat!”

The axe remained hanging on John’s arm.

A ball cut the closest of the three canoes in half

A second ball whistled over his head and cut the closest of the three canoes in half, while a “Hurrah!” burst out on board the Duncan.

The frightened savages fled, and returned to the coast.

“To us! To us, Tom!” shouted John Mangles in a loud voice.

And, a few moments later, the ten fugitives, without knowing how, without understanding anything, were all safely aboard the Duncan.

1. Kauri gum has many uses, both by the Māori, and for export markets. It was one of New Zealand’s principle exports in the 19th and early 20th centuries — DAS

2. Dr. von Hochstetter, et al were mistaken. It is now generally accepted that all varieties of Dinornis had gone extinct by the 15th century — DAS

3. Megatheriums, yes. Pterodactyls, no. Pterosaurs had been extinct for sixty-five million years or so before either megatheriums of moas arrived on the scene — DAS

4. Verne has this distance as “nearly a hundred miles” and not as much progress as John had hoped to make in ten days.