They attacked the rocky mass with levers

The next day, February 17th, the first rays of the rising sun awakened the sleepers on Maunganamu. The Māori had been stirring for some time, coming and going from around the foot of the cone, without abandoning their encirclement. A furious clamour greeted the appearance of the Europeans coming out of the desecrated enclosure.

Each of them took their first look at the surrounding mountains; deep valleys, still drenched in mists; and the surface of Lake Taupo, rippled by the morning breeze.

Then they all gathered around Paganel expectantly, anxious to learn about his new project.

Paganel immediately responded to the eager curiosity of his companions. “My friends, my project has the advantage that if it does not produce all the effect I expect, even if it fails completely, our situation will not be worse. But it must succeed; it will succeed.”

“And this project?” asked MacNabbs.

“Here it is,” said Paganel. “The natives’ superstition has made this mountain a place of asylum; superstition will help us to get off of it. If we succeed in persuading Kai-Kúmu that we have been the victims of our desecration, that heavenly wrath has struck us, that we died a terrible death, do you believe that he will abandon this plateau? Leave Maunganamu and return to his village?”

“That is likely,” said Glenarvan.

“And with what horrible death are you threatening us?” asked Lady Helena.

“The death of desecrators, my friends,” answered Paganel. “The vengeful flames are under our feet. Let us open them!”

“What? You want to make a volcano!” exclaimed John Mangles.

“Yes, a dummy volcano, an improvised volcano, whose fury we will direct! There is a whole supply of steam and underground fire waiting to come out! Let’s organize an artificial eruption for our benefit!”

“That’s quite an idea,” said the Major. “Well imagined, Paganel!”

“You understand,” said the geographer, “that we will pretend to be devoured by the flames of the Māori Pluto, and that we will disappear spiritually into the tomb of Kára-Téte, where we will stay three, four, five days, if necessary, until the savages, convinced of our death, abandon the field.”

“But what if they want to witness our punishment?” asked Miss Grant, “What if they climb the mountain?”

“No, my dear Mary,” said Paganel. “They will not do it. The mountain is tapu, and when she has devoured her profaners herself, her tapu will be even stronger!”

“This really is a good idea,” said Glenarvan. “The only way it can go wrong is if the savages persist in staying so long at the foot of Maunganamu that we run out of food. But this is unlikely, especially if we play our game skillfully.”

“And when will we try this last chance?” asked Lady Helena.

“This very evening,” said Paganel, “as soon as it is fully dark.”

“Agreed,” said MacNabbs. “Paganel, you are a man of genius and I — who do not easily get excited — anticipate a great success. Ah, those scoundrels! We will serve them a little miracle, which will delay their conversion by a good century! May the missionaries forgive us!”

Paganel’s plan was adopted, and truly, with the superstitious beliefs of the Māori, it had every chance of success. Only its execution remained. The idea was good, but its implementation difficult. Would this volcano devour those daring to create a crater in it? Could they control, and direct, this eruption when its vapours, flames, and lava were unleashed? Might the entire cone sink into a pit of fire? They were touching one of those phenomena on which nature reserved an absolute monopoly.

Paganel had foreseen these difficulties, so he intended to act with caution, and without pushing things to the extreme. It only took the appearance to deceive the Māori, and not the terrible reality of an eruption.

The day seemed very long. Everyone counted the endless hours. Everything was prepared for the escape. The provisions of the Údu pá had been divided into small, manageable packs. A few mats and firearms taken from the chief’s tomb completed this light baggage. It goes without saying that these preparations were made inside the palisaded enclosure, out of sight from the savages.

At six o’clock the steward served a comforting meal. Where and when they would eat in the valleys of the district, no one could foresee, so they dined for the future. The main dish consisted of half a dozen big stewed rats that Wilson had caught. Lady Helena and Mary Grant stubbornly refused to taste this game so esteemed in New Zealand, but the men feasted like real Māori. This flesh was really excellent, even tasty, and the six rodents were gnawed to the bone.

Evening twilight arrived. The sun disappeared behind a band of thick, stormy clouds. A few lightning flashes illuminated the horizon, and distant thunder rolled across the depths of the sky.

Paganel hailed the storm that helped his plans and completed his staging. The savages are superstitiously affected by these great phenomena of nature. The Māori believe the thunder to be the irritated voice of Nui Atua and the lightning is the angry flashing of his eyes. The deity would therefore appear to personally punish the profaners of the tapu. At eight o’clock, the summit of Maunganamu disappeared in a sinister darkness. The sky gave a black background to the blossoming of flames that Paganel’s hand was about to produce. The Māori could no longer see their prisoners. The moment to act had come.

It had to be done quickly. Glenarvan, Paganel, MacNabbs, Robert, the steward, and the two sailors, set to work together.

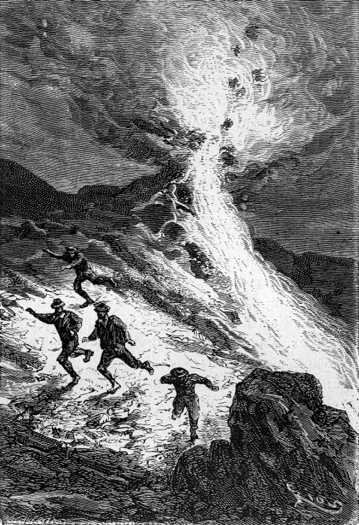

They attacked the rocky mass with levers

The location of the crater was chosen thirty paces from the tomb of Kára-Téte. It was important, even critical, that the Údu pá was spared by the eruption, because without it, the tapu of the mountain would be erased. Paganel had noticed an enormous block of stone there, around which vapours poured out especially strongly. This block covered a small natural crater dug in the cone, and its weight alone opposed the effusion of the underground flames. If it could be thrown out of its cavity, the vapours and lava would immediately burst through the open vent.

The workers made levers with the poles pulled up from inside the Údu pá, and vigorously attacked the rocky mass. Under their simultaneous efforts, the rock soon began to shake. They had dug a shallow trench below it on the slope of the mountain, so that it could slip on this inclined plane. As they lifted it up, the vibrations of the ground became more violent.

Dull roars of flame, and the whistling of a furnace ran under the thinned crust. The daring workmen, veritable cyclopes wielding the fires of the earth, worked silently. Soon, a few cracks and jets of burning steam told them that the place was becoming dangerous. A final effort tore the block loose, and it slid down the slope of the mount and disappeared.

The thinned layer immediately yielded. A violent detonation sent an incandescent column shooting up into the sky, while streams of boiling water and lava flowed toward the natives’ encampment in the lower valley.

An incandescent column shot up into the sky

The whole cone shook, as if it was about to collapse into a bottomless chasm. Glenarvan and his companions barely had time to escape the eruption. They fled to the enclosure of the Údu pá, while being hit by a few drops of nearly boiling water. This water at first gave off a slight odour of broth, which soon changed into a very strong odour of sulphur.

The mud, lava, and volcanic ash were merged into the same conflagration. Torrents of fire crisscrossed the flanks of Maunganamu. The nearby mountains lit up with the fire of the eruption. The deep valleys echoed with intense reverberations.

All the savages had risen, screaming under the bite of the lava burning into the middle of their bivouac. Those whom the river of fire had not overwhelmed fled up the surrounding hills. They turned, frightened, and surveyed this frightful phenomenon: the volcano with which the wrath of their god had destroyed the profaners of the sacred mountain. At moments when the roar of the eruption waned, they could be heard screaming their sacramental cry.

“Tapu! Tapu! Tapu!”

A huge quantity of vapour, burning stones, and lava escaped from the new crater of Maunganamu. It was no longer a mere geyser, like those near Mount Hecla in Iceland, but Mount Hecla itself. All this volcanic suppuration had hitherto been contained under the envelope of the cone, because the valves of Tongariro were sufficient for its release. But when a new escape opened, it rushed out with extreme vehemence, and that night, by a law of equilibrium, the other eruptions of the island were to lose their usual intensity.

An hour after the debut of this volcano on the world stage, large streams of incandescent lava flowed on its flanks. A whole legion of rats could be seen coming out of their uninhabitable holes and fleeing the burning ground.

During the whole night and under the storm that was unleashed in the heights of the sky, the cone shook with a violence that worried Glenarvan. The eruption gnawed at the edges of the crater.

The prisoners, hidden within the palisade, followed the frightful progress of the phenomenon.

The morning came. The volcanic fury did not abate. Thick yellowish vapour mingled with the flames; the streams of lava wound out on all sides.

Glenarvan kept watch, his heart throbbing, glancing through the interstices of the stockade and observing the natives’ encampment.

The Māori had fled to neighbouring plateaus, out of reach of the volcano. Some corpses lying at the foot of the cone were charred by the fire. Farther on, toward the pā, the lava had destroyed about twenty huts, which still smoked. The Māori, in scattered groups, regarded Maunganamu’s shrouded summit with a religious terror.

Kai-Kúmu came, surrounded by his warriors, and Glenarvan recognized him. The chief advanced to the foot of the cone, on the side untouched by the lava, but he did not ascend even the lowest slopes.

There, his arms outstretched like a sorcerer performing an exorcism, he made a few gestures whose meaning did not escape the prisoners. As Paganel had foreseen, Kai-Kúmu was laying a stronger tapu on the vengeful mountain.

Soon after, the natives filed away down the winding paths that led back to the pā.

“They’re leaving!” exclaimed Glenarvan. “They’ve given up! God be praised! Our stratagem has succeeded! My dear Helena, my good companions, we are dead, and here we are buried! But tonight, we will be resurrected; we will leave our tomb; we will flee these barbarous tribes!”

It would be difficult to imagine the joy that reigned in the Údu pá. Hope had risen in all their hearts. These courageous travellers forgot the past, forgot the future, and thought only of the present! And yet they still had the difficult task of reaching some European settlement in the midst of this unknown country. But with Kai-Kúmu outwitted, they thought they were saved from all the savages of New Zealand!

The Major, for his part, did not hide the utter contempt in which he held the Māori, and he did not lack the words to express it. It became a contest between him and Paganel. They called them unforgivable brutes, stupid donkeys, Pacific idiots, Bedlam savages, antipodean cretins, etc., etc. They did not run out of epithets.

A whole day had to pass before the final escape. It was employed discussing a flight plan. Paganel had preciously kept his map of New Zealand, and he was able to seek the safest ways.

After discussion, the fugitives resolved to move northeast, toward the East Cape.1 They would be passing through unknown but probably deserted territory. The travellers, already accustomed to extricating themselves from natural difficulties, and overcoming physical obstacles, feared nothing but meeting the Māori. They wanted to avoid them at all costs, and to reach the northeastern tip of the island, where missionaries had founded a few settlements. Moreover, that part of the island had so far escaped the disasters of the war, and native parties were not beating the countryside.

The distance between Lake Taupo and the East Cape was estimated to be 140 miles:2 two weeks of walking at ten miles a day. This could be done; it would be exhausting, but in this courageous troop no one counted their steps. Once they reached a mission, the travellers could rest there while waiting for a favourable opportunity to go on to Auckland, since this city was still their ultimate destination.

These various points decided, they continued to watch the natives until evening. There were none left at the foot of the mountain, and when the valleys around Lake Taupo fell into the shadows, no fire marked the presence of Māori at the bottom of the cone. The path was clear.

At nine o’clock, in the dark of night, Glenarvan gave the signal to depart. He and his companions, armed and equipped at the expense of Kára-Téte, began to cautiously descend the ramps of Maunganamu. John Mangles and Wilson were in the lead, ears and eyes on watch. They stopped at the slightest sound, they investigated the slightest gleam. Each of them crawled down the slope of the mountain to be better concealed by it.

Two hundred feet above the plateau, John Mangles and his sailor reached the perilous ridge that had been defended so obstinately by the natives. If, unfortunately, the Māori were more cunning than the fugitives, and had feigned a retreat to lure them down — if they had not been duped by the volcanic eruption — this was where their trap would be set. Glenarvan, despite all his confidence and despite Paganel’s jokes, could not help but shudder. The salvation of his people was going to be played out during the ten minutes necessary to cross this crest. Lady Helena clung to his arm. He could feel her heart beating.

He did not consider going back. Neither did John. The young captain, hidden by the complete darkness, and followed by the rest, crept along the narrow ridge, stopping when some loose stone rolled to the bottom of the plateau. If the savages were still waiting in ambush below, these unusual noises would have provoked a furious fusillade from both sides.

The fugitives did not go quickly, slipping like a snake across the inclined ridge. When John Mangles reached the lowest point, only twenty-five feet separated him from the plateau where the natives had camped the night before. The ridge now rose up in a steep slope to a copse of trees, a quarter of a mile ahead.

They crossed the low saddle of the ridge without accident, and the travellers began to go up in silence. The cluster of trees was invisible, but they knew it was there. And provided a native ambush was not prepared in it, Glenarvan hoped for it to be a safe place. However, he knew that from this moment he was no longer protected by the tapu. The rising ridge did not belong to Maunganamu, but to the mountainous system that bristled on the eastern side of Lake Taupo. So, not only the natives’ gunshots, but a hand-to-hand attack was to be feared.

For ten minutes the little troop rose almost imperceptibly toward the upper plateau. John could not yet see the dark copse, but it must have been less than two hundred feet away.

Suddenly he stopped, and almost backed up. He thought he heard some noise in the darkness. His hesitation stopped the movement of his companions.

He remained motionless, and that was enough to disturb those who followed him. They waited in inexpressible anguish! Would they be forced to go back and return to the summit of Maunganamu?

But John, finding that the noise was not repeated, resumed his ascent up the narrow path of the ridge.

Soon the copse was vaguely outlined in the shadows. A few more steps and they reached it, and the fugitives huddled under the thick foliage of the trees.

1. Verne’s description of where they plan to go makes no sense. He says that they plan to go east, to the Bay of Plenty, on the east coast. The Bay of Plenty is north of Lake Taupo, on the northern coast. Where he has them end up is near the East Cape, so that’s where I say they plan to go. (It’s further confused by the map included in the Hetzel edition, which shows them going to a point on the Bay of Plenty, nowhere near where text describes them going) — DAS

2. 56 leagues (225 kilometres) — DAS