“This islet is a paradise”

You do not die of joy, because the father and the children came back to life even before they had reached the yacht. How to paint this scene? Words do not suffice. The whole crew was crying when they saw these three people joined in a mute embrace. Harry Grant, arrived on deck and fell to his knees. The pious Scott wished, by touching what to him was the soil of his country, to thank God, before all, for his deliverance.

Then, turning to Lady Helena, Lord Glenarvan and their companions, he gave them thanks in a voice broken by emotion. His children had told him the outline of the voyage of the Duncan during the short crossing from the islet to the yacht.

What an immense debt he had contracted toward this noble woman and her companions! From Lord Glenarvan to the least of the sailors, they had all struggled and suffered for him! Harry Grant expressed the feelings of gratitude that flooded his heart with so much simplicity and nobility, his face illuminated with such pure and gentle emotion, that the entire crew felt rewarded and more for all the hardships they had suffered. Even the impassive Major’s eye wet with a tear that he could not restrain. As for the worthy Paganel, he cried like a child who does not think to hide his tears.

Harry Grant never tired of looking at his daughter. He thought her beautiful, and charming! He said it to himself and said again aloud, with Lady Helena as his witness, as if to certify that his paternal love did not mislead him.

Then, he turned to his son. “You have grown up! You’ve become a man!” he cried with delight.

And he lavished on these two people, so dear to him, the thousand kisses piled up in his heart during two years of absence.

Robert introduced him in turn to all of his friends, and found means of varying his formulas, although he had to say the same of each one! It was because everyone was perfect in the boy’s eyes. When it was John Mangles’ turn to be introduced, the captain blushed like a girl and his voice trembled as he spoke to Mary’s father.

Lady Helena then told Captain Grant more of the story of the trip, and she made him proud of his son, and his daughter.

Harry Grant learned of the exploits of the young hero, and how this child had already paid Lord Glenarvan a portion of the paternal debt. Then, in turn, John Mangles spoke of Mary in such terms that Harry Grant, guided by a few hints from Lady Helena, put his daughter’s hand in the valiant hand of the young captain.

He turned to Lord and Lady Glenarvan. “My Lord, and you, Madame,” he said. “Bless our children!”

When all was said and said again a thousand times, Glenarvan told Harry Grant about Ayrton. Grant confirmed the quartermaster’s confession about his landing on the Australian coast.

“He is an intelligent, audacious man,” he said, “whose passions have thrown him to evil. May reflection and repentance bring him back to better feelings!”

But before Ayrton was transferred to Maria Theresa Island, Harry Grant wanted to do the honours of his rock for his new friends. He invited them to visit his wooden house and sit at the table of the Pacific Robinsons. Glenarvan and his companions wholeheartedly agreed. Robert and Mary Grant were burning with the desire to see these lonely places where their father had shed so many tears.

A boat was prepared, and the father, the two children, Lord and Lady Glenarvan, the Major, John Mangles, and Paganel soon landed on the shores of the island.

A few hours were enough to see all of Harry Grant’s estate. It was the summit of an underwater mountain, a plateau where basaltic rocks abounded with volcanic debris. In the geological epochs of the earth, this mountain had gradually risen from the depths of the Pacific under the action of subterranean fires. But for centuries the volcano had been a peaceful mountain, its crater filled, an island emerging from the liquid plain. Topsoil had formed and the vegetable kingdom established itself in this new earth. A few passing whalers had landed some domestic animals, goats and pigs, which multiplied in the wild, and now nature manifested itself in its three kingdoms on this island lost in the middle of the ocean.

When the castaways of the Britannia had taken refuge there, the hand of man came to regularize the efforts of nature. In two and a half years, Harry Grant and his sailors metamorphosed their islet. Several acres of land, cultivated with care, produced vegetables of excellent quality.

The visitors arrived at the house shaded by verdant gum trees. The magnificent sea stretched in front of its windows, sparkling in the rays of the sun. Harry Grant had his table set in the shade of the beautiful trees, and everyone took their place. A leg of kid, some nardoo bread, some bowls of milk, a few roots of wild chicory, and a pure and fresh water formed the elements of this simple meal, worthy of the shepherds of Arcadia.

Paganel was delighted. His old ideas of becoming a Robinson came back into his head.

“This islet is a paradise”

“That rascal Ayrton is not be to be pitied!” he cried in his enthusiasm. “This islet is a paradise.”

“Yes,” said Harry Grant, “a paradise for three poor shipwrecked men whom Heaven guarded! I regret that Maria Theresa is not a vast and fertile island, with a river instead of a stream and a harbour instead of a cove beaten by the waves of the open sea.”

“Why, Captain?” asked Glenarvan.

“Because then I could have laid here the foundation for the colony I want to give to Scotland in the Pacific.”

“Ah! Captain Grant,” said Glenarvan. “You have not abandoned the idea which has made you so popular in our old country?”

“No, My Lord, and God has saved me by your hands only to allow me to accomplish it. It is necessary that our poor brothers of old Caledonia, all those who suffer, have a refuge against misery in a new land! Our dear country must possess a colony of her own in these seas, where she can find a little of the independence and well-being which she lacks in Europe!”

“Ah! That’s right, Captain Grant,” said Lady Helena. “It is a beautiful project, and worthy of a big heart. But this islet…?”

“No, Madame, it is a good rock to feed at most a few colonists, while we need a vast and rich land with all the treasures of the first ages.”

“Well, Captain,” said Glenarvan. “The future is ours, and we will seek this land together!”

Harry Grant and Glenarvan exchanged a warm handshake, as if to ratify this promise.

Then, on this very island, in this humble house, everyone wanted to know the story of the castaways of the Britannia during their two long years of abandonment. Harry Grant hastened to satisfy the curiosity of his new friends.

“My story,” he said, “is that of all the Robinsons thrown on an island, and who, being able to rely only on God and themselves, feel that they have the duty of disputing for their lives with the elements!

“It was during the night of June 26th to 27th, 1862, that the Britannia, in distress after six days of storm, broke on the rocks of Maria Theresa. The sea was stormy, rescue impossible, and all my unhappy crew perished. Only my two sailors — Bob Learce, Joe Bell, and I — managed to reach the coast after twenty unsuccessful attempts!

“The land that received us was only a desert island, two miles wide, five miles long, with about thirty trees in the interior, a few meadows and a source of fresh water that fortunately never dries up. Alone with my two sailors, in this corner of the world, I did not despair. I put my trust in God, and I prepared to fight, resolutely. Bob and Joe, my brave companions in misfortune, my friends, assisted me energetically.

“We began — like our model, the ideal Robinson of Daniel Defoe — by collecting the wreckage from the ship: tools, a little powder, weapons, a bag of precious seeds. The first days were difficult, but soon hunting and fishing provided us with food, because wild goats swarmed inside the island, and marine animals abounded on its coasts. Gradually the work for our survival became routine.

“I measured the position of the island exactly with my instruments, which I had saved from sinking. This discovery placed us out of the shipping lanes, and we could not be rescued unless by a providential chance. While thinking of those who were dear to me and whom I no longer hoped to see again, I bravely accepted this trial, and the names of my two children were mixed daily with my prayers.

“We worked hard. Soon several acres of land were sown with the seeds from the Britannia. Potatoes, chicory, and sorrel fortified our usual diet, then other vegetables. We captured a few kid goats, which were easily tamed. We had milk, butter. The nardoo, which grew in dried up creeks, furnished us with a kind of substantial bread, and material life no longer inspired us with fear.

“We had built a clapboard house with debris from the Britannia. It was roofed with carefully tarred sails, and the rainy season passed happily under this solid shelter. There, we discussed many plans, many dreams, the best of which has just been realized!

“At first, I had the idea of facing the sea on a canoe made with the wreckage of the ship, but fifteen hundred miles separated us from the nearest land, that is to say, the islands of the Pomotou Archipelago. No small boat could have withstood such a long voyage. So I gave it up, and I waited for my salvation by no more than a divine intervention.

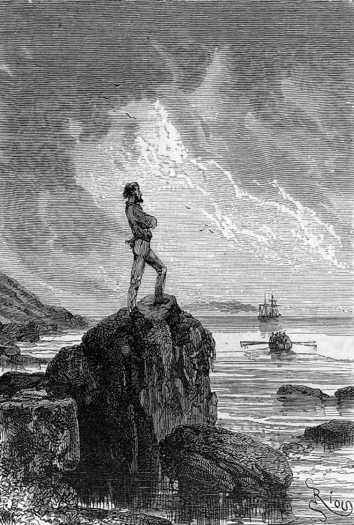

“Ah! My poor children! How many times, from the high rocks of the coast, have we watched far off ships? During the whole time that our exile lasted, only two or three sails appeared on the horizon, only to disappear immediately! Two and a half years passed thus. We did not hope anymore, but we did not yet despair.

“Finally, yesterday, I was on the highest peak of the island, when I saw a slight smoke in the west. It grew bigger. Soon a ship became visible to me. She seemed to be heading toward us. But would she avoid this islet that offered her no harbour?

“Ah! What a day of anguish, and how did my heart not break in my breast! My companions lit a fire on one of Maria Theresa’s peaks. Night came, but the yacht made no signal of recognition! Salvation was right there! Were we to see it disappear?

“I did not hesitate any more. The darkness was growing. The ship could round the island during the night. I threw myself into the sea and headed for her. Hope tripled my strength. I split the waves with superhuman vigour. I was nearing the yacht, scarcely thirty fathoms away, when she tacked!

“Then I uttered those desperate cries that my two children alone heard, and which had not been an illusion.

“I returned to the shore, exhausted, overcome by emotion and fatigue. My two sailors collected me, half-dead. That last night we passed on the island was horrible, and we thought we were still abandoned. But then, when the day came, I saw the yacht running along under a low steam. Your boat was put to sea! We were saved, and — divine goodness from Heaven — my children, my dear children, were there, stretching out their arms!”

Harry Grant’s story ended with kisses and hugs from Mary and Robert. And it was only then that the captain learned that he owed his rescue to the rather hieroglyphic document, which he had shut up in a bottle and entrusted to the caprices of the waves, eight days after his shipwreck.

But what was Jacques Paganel thinking during Captain Grant’s story? The worthy geographer turned the words of the document over in his brain a thousand times! He recalled those three successive interpretations, all three wrong! How was this island of Maria Theresa indicated on these papers gnawed by the sea? Paganel could not hold back any longer.

He grabbed Captain Grant by the hand. “Captain, will you finally tell me what was in your indecipherable document?”

Everyone shared the geographer’s curiosity. They all wanted to hear the answer to the riddle that they had sought for nine months. They were finally going to be told.

“Well, Captain,” asked Paganel. “Do you remember the precise wording of the document?”

“Exactly,” said Harry Grant, “and not a day has passed without my memory recalling those words to which our only hope was attached.”

“And what are they, Captain?” asked Glenarvan. “Tell us, because our pride is stung.”

“I am ready to satisfy you,” said Harry Grant, “but you know that to increase the chances of salvation, I had enclosed three documents written in three languages in the bottle. Which one do you want to know?

“So they are not identical?” exclaimed Paganel.

“As close as I could make them.”

“Well, quote the French document,” said Glenarvan. “It is the one that the waves have respected most, and it has mainly served as a basis for our interpretations.”

“My Lord, here it is word for word,” said Harry Grant.

“27 juin 1862, le trois-mâts Britannia, de Glasgow, s’est perdu à quinze cents lieues de la Patagonie, dans l’hémisphère austral. Portés à terre, deux matelots et le capitaine Grant ont atteint à l’île Tabor…”

“Huh!” said Paganel.

Captain Grant continued.

“…là, continuellement en proie à une cruelle indigence, ils ont jeté ce document par 153° de longitude et 37° 11′ de latitude. Venez à leur secours, ou ils sont perdus.”

At that name of ‘Tabor,’ Paganel had risen abruptly; then, no longer containing himself, he exclaimed: “How, ‘l’île Tabor?’ But it’s ‘Maria Theresa Island!’”

“No doubt, Mr. Paganel,” said Harry Grant. “‘Maria Theresa’ on the English and German charts, “but ‘Tabor’ on the French charts!”

At that moment, a tremendous punch hit Paganel’s shoulder, who folded in shock. The truth requires it to be said that it was addressed to him by the Major, abandoning for the first time his careful habit of conviviality.

“Geographer!” said MacNabbs with the tone of the deepest contempt.

But Paganel had not even felt the Major’s hand. What was it, compared to the geographical blow that overwhelmed him?

He had Captain Grant recite the words of the English document, which went thus:

“June 27, 1862. The three-master Britannia, of Glasgow, sank fifteen hundred leagues from Patagonia, in the Southern Hemisphere, stranding two sailors and their skipper, Harry Grant. They have landed on Maria Theresa Island. Continually plagued by cruel poverty, they threw this document into the sea at 153° of longitude and 37° 11’ of latitude. Bring them assistance, or they are lost.”

So, as Paganel told Captain Grant, he had nearly arrived at the truth! He had deciphered almost the entirety the indecipherable document! In turn, the names of Patagonia, Australia, and New Zealand had appeared to him with irrefutable certainty. ‘Contin,’ first continent, had gradually assumed its true meaning of continual. ‘Indi’ had successively meant Indians, natives, then finally indigence, its true meaning. Only the fragment ‘abor’ had deceived the wisdom of the geographer! Paganel had stubbornly made it the radical of the verb aborder, to approach, when it was the proper name — the French name — of Tabor Island, the island which served as a refuge for the Britannia’s castaways! An error easy to understand, however, since all the maps on the Duncan gave this islet the name of Maria Theresa.

“It does not matter!” exclaimed Paganel, tearing at his hair, “I should not have forgotten this double name! It is an unforgivable mistake. An unworthy error for un Secrétaire de la Société de Géographie! I am dishonoured!”

“Monsieur Paganel,” said Lady Helena. “Please, calm yourself!”

“No, Madam! No! I am an ass!”

“And not even a learned ass!” said the Major, as a consolation.

When the meal was over, Harry Grant put everything in his house in order. He took nothing, wanting Ayrton to inherit the riches of an honest man.

They came back on board. Glenarvan planned to leave that day, and gave his orders for the landing of the quartermaster. Ayrton was brought to the poop, and found himself in the presence of Harry Grant.

“It’s me, Ayrton,” Grant said.

“It’s you, Captain,” said Ayrton, pretending not to be surprised to see him. “Well, I’m not sorry to see you in good health.”

“It seems, Ayrton, that I made a mistake in landing you on an inhabited land.”

“It seems so, Captain.”

“You will replace me on this desert island. May Heaven inspire you with repentance!”

“So be it!” Ayrton answered calmly.

Glenarvan addressed the quartermaster. “You persist, Ayrton, in this resolution to be abandoned?”

“Yes, My Lord.”

“Tabor Island suits you?”

“Perfectly.”

“Now listen to my last words, Ayrton. Here you will be, far from any land, and without any possibility of communication with your fellow men. Miracles are rare, and you will not be able to flee this islet where the Duncan leaves you. You will be alone, under the eye of a God who reads the deepest hearts, but you will not be lost or ignored, as was Captain Grant. As unworthy as you are of men’s remembrance, men will remember you. I’ll know where you are, Ayrton, I’ll know where to find you, I’ll never forget it.”

“God preserve Your Honour!” said Ayrton simply.

These were the last words exchanged between Glenarvan and the quartermaster. The boat was ready. Ayrton climbed down into it.

John Mangles had previously shipped some boxes of preserved food, tools, weapons, and a supply of powder and lead to the island. The quartermaster could therefore rehabilitate himself with work. Nothing was lacking, not even books, and among others the Bible, so dear to English hearts.

The hour of separation had come. The crew and passengers stood on the deck. More than one felt a tightness in their soul. Mary Grant and Lady Helena could not contain their emotion.

“Must it be so?” the young woman asked her husband. “Is it necessary that this unfortunate man be abandoned?”

“It must be, Helena,” said Lord Glenarvan. “It is his expiation!”

The boat, commanded by John Mangles, pushed off. Ayrton, standing, still impassive, took off his hat and bowed gravely.

Glenarvan found himself, and with him all his crew, as one does before a man who is going to die, and the boat moved away in the middle of a deep silence.

The quartermaster stood motionless, his arms crossed

Ayrton, arrived at the beach, jumped onto the sand, and the boat came back to the ship. It was four o’clock in the evening, and from the top of the poop the passengers could see the quartermaster, arms crossed, motionless as a statue on a rock, looking at the ship.

“Are we leaving, My Lord?” asked John Mangles.

“Yes, John,” said Glenarvan, more excited than he wished to appear.

“Full steam!” John shouted to the engineer.

The steam whistled in its pipes, the screw beat the waves, and at eight o’clock the last summits of Tabor Island disappeared in the shadows of the night.