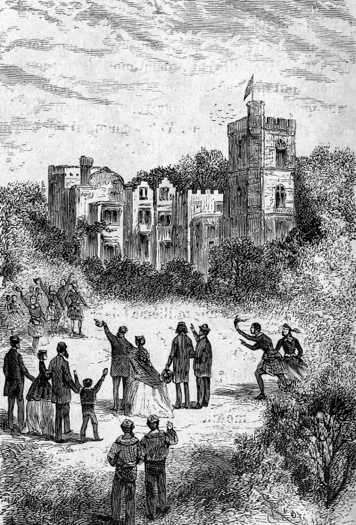

They entered Malcolm Castle, to the “Hurrah!”s of the Highlanders

The Duncan sighted the American coast on the 18th of March, eleven days after leaving Tabor Island, and she anchored the next day in Talcahuano Bay.

She returned after a journey of five months, during which, strictly following the line of the 37th parallel, she had circumnavigated the world. The passengers of this memorable expedition, unprecedented in the annals of the traveller’s club, had crossed Chile, the Pampas, the Argentine Republic, the Atlantic, the da Cunha Islands, the Indian Ocean, the Amsterdam Islands, Australia, New Zealand, Tabor Island, and the Pacific. Their efforts had not been fruitless, and they repatriated the castaways of the Britannia.

Not one of those brave Scots who had answered the call of their laird was missing from the roll. They were all returning to their old Scotland, and this expedition recalled history’s “battle without tears.”1

The Duncan, her refuelling completed, followed the coast of Patagonia south, doubled Cape Horn, and sailed across the Atlantic Ocean.

No trip was less incidental. The yacht carried a cargo of happiness within it. There were no secrets aboard, not even the feelings of John Mangles for Mary Grant.

A mystery still intrigued MacNabbs, however. Why did Paganel always remain tightly bundled up in his clothes, and wrapped in a scarf that went up to his ears? The Major greatly desired to know the reason for this singular mania. But in spite of the all the interrogations, the allusions, the suspicions of MacNabbs, Paganel did not unbutton himself.

No, not even when the Duncan crossed the equator and the seams of the bridge melted under a heat of fifty degrees.2

“He is so distracted, that he thinks himself in St. Petersburg,” said the Major, seeing the geographer enveloped in a huge greatcoat, as if the mercury had been frozen in the thermometer.

They entered Malcolm Castle, to the “Hurrah!”s of the Highlanders

Finally, on May 9th, fifty-three days after leaving Talcahuano, John Mangles raised the light of Cape Clear. The yacht entered the St. George’s Channel, crossed the Irish Sea, and on the 10th of May, she reached the Firth of Clyde. At eleven o’clock she was anchoring at Dumbarton. At two o’clock in the afternoon her passengers entered Malcolm Castle, to the “Hurrah!”s of the Highlanders.

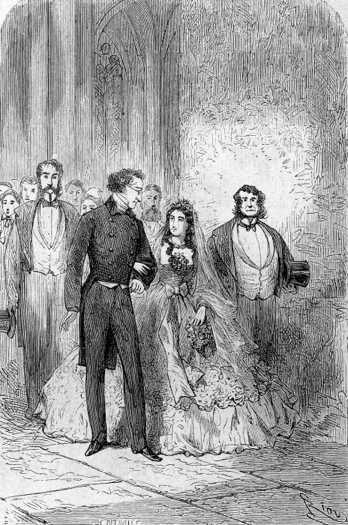

It was thus written that Harry Grant and his two companions would be saved, that John Mangles would marry Mary Grant in the old St. Mungo’s Cathedral, where Reverend Morton — who had prayed nine months earlier for the salvation of the father — blessed the marriage of his daughter and his saviour! It was therefore written that Robert would be a sailor like Harry Grant and John Mangles, and that he would take up with them the great project of Captain Grant, under the patronage of Lord Glenarvan!

But was it also written that Jacques Paganel would not die a bachelor? Probably.

In fact, the learned geographer could not escape celebrity after his heroic exploits. His distractions created a sensation in Scottish society. His modesty was insufficient to extract him from the attention lavished on him.

And it was then that an amiable thirty year old young lady — Major MacNabbs’ cousin, no less — a little eccentric herself, but still good and charming, fell for the singularities of the geographer and offered him her hand. Forty thousand pounds sterling came with it, but no one mentioned that.

Paganel was far from insensitive to Miss Arabella’s feelings, but he did not dare to answer her.

It was the Major who matched these two hearts, made for each other. He even told Paganel that marriage was the “last distraction” he would be allowed.

It was a great embarrassment to Paganel, who, by a strange singularity, could not come to articulate the fatal word.

“Miss Arabella does not please you?” MacNabbs kept asking.

“Oh, Major, she is charming!” cried Paganel. “A thousand times too charming, and, if it is necessary to tell you everything, I would like her more if she were less! I wish she had a fault.”

“Rest easy,” said the Major. “She has, and more than one. The most perfect woman still has her quota. So, Paganel, is it decided?”

“I do not dare,” said Paganel.

“Come, my learned friend, why are you hesitating?”

“I am unworthy of Miss Arabella!” the geographer invariably answered. And he would not say more than that.

Finally, the Major backed him against a wall one day, and Paganel entrusted to him, under the seal of secrecy, a peculiarity which would facilitate his identification, if the police were ever on his heels.

“Bah!” cried the Major.

“It’s like I tell you,” said Paganel.

“What does it matter, my worthy friend?”

“You think?”

“On the contrary, this adds to your personal merits! You are only more singular. This makes you the unmatched man of Arabella’s dreams!”

And the Major, keeping an imperturbable seriousness, left Paganel prey to the most poignant anxieties.

A short interview took place between MacNabbs and Miss Arabella.

A wedding was celebrated fifteen days later

Fifteen days later, a wedding was loudly celebrated in the Malcolm Castle Chapel. Paganel was gorgeous, but tightly buttoned, and Miss Arabella splendid.

And the geographer’s secret would have always remained buried in the depths of the unknown, if the Major had not spoken to Glenarvan, who did not hide it from Lady Helena, who had a word with Mrs. Mangles. Shortly the secret reached the ears of Mrs. Olbinett, and it burst forth.

Jacques Paganel, during his three days of captivity with the Māori, had been tattooed. Tattooed from his feet to his shoulders, and he wore on his breast the image of a heraldic kiwi with outstretched wings, which pecked at his heart.

This was the only adventure of his great journey to which Paganel never consoled himself, and he did not forgive New Zealand. It was also what, in spite of many solicitations and despite his regrets, prevented him from returning to France. He would have feared his person exposing the entire Geographic Society to the jokes of caricaturists and tabloids, by bringing back a freshly tattooed Secretary.

Captain Grant’s return to Scotland was hailed as a national event and Harry Grant became the most popular man in Old Caledonia. His son Robert became a sailor like himself, and Captain John, and it was under the auspices of Lord Glenarvan that he resumed the project of founding a Scottish colony in the Pacific Seas.

The End

1. The Battle of Brécourt, July 13th, 1793, during the French Revolution, became known as the “bataille «sans larmes»”. Fifteen hundred National Convention forces surprised a force of five thousand Federalists, near Pacy-sur-Eure. The Federalist forces broke and ran at the first sound of cannon fire, and there were no deaths or injuries on either side — DAS

2. 122° Fahrenheit — DAS