Paganel spoke with superb animation

The Secretary of the Geographical Society was evidently an amiable man, for all this was said in a most charming manner. Lord Glenarvan knew quite well who he was now, for he had often heard Paganel spoken of, and was aware of his merits. His geographical works, his reports on modern discoveries inserted into the reports of the Society, and his world-wide correspondence, gave him a most distinguished place among the scholars of France.

Lord Glenarvan could not but welcome such a guest, and shook hands cordially. “And now that our introductions are over,” he added, “you will allow me, Monsieur Paganel, to ask you a question?”

“Twenty, My Lord, “ replied Paganel. “It will always be a pleasure to converse with you.”

“Was it last evening that you came on board this ship?”

“Yes, My Lord, about eight o’clock. I jumped into a cab at the Caledonian Railway, and from the cab into the Scotia, where I had booked my cabin before I left Paris. It was a dark night, and I saw no one on board, so I found cabin number six, and went to my berth immediately — for I had heard that the best way to prevent sea-sickness is to go to bed as soon as you start, and not to stir for the first few days; and, moreover, I had been traveling for thirty hours. So I tucked myself in, and slept conscientiously, I assure you, for thirty-six hours.”

Paganel’s listeners understood the whole mystery of his presence on the Duncan, now. The French traveller had mistaken his vessel, and gone on board while the crew were attending the service at St. Mungo’s. All was explained. But what would the learned geographer say, when he heard the name and destination of the ship in which he had taken passage?

“Then it is Calcutta, Monsieur Paganel, that you have chosen as your point of departure on your travels?”

“Yes, My Lord, to see India is an idea I have cherished all my life. It will be the realization of my fondest dreams, to find myself in the country of elephants and Thugs.”

“Then it would be by no means a matter of indifference to you, to visit another country instead.”

“No, My Lord; indeed it would be very disagreeable, for I have letters of recommendation from Lord Somerset to the Governor-General of India, and also a mission to execute for the Geographical Society.”

“Ah, you have a mission?”

“Yes, I have to attempt a curious and important journey, the plan of which has been drawn up by my learned friend and colleague, M. Vivien de Saint Martin. I am to pursue the track of the Schlaginweit Brothers; and Colonels Waugh and Webb, and Hodgson; and Huc and Gabet, the missionaries; and Moorecroft and M. Jules Remy, and so many celebrated travellers. I mean to try and succeed where Krick, the missionary so unfortunately failed in 1846; in a word, I want to follow the course of the Yarou-Dzangbo-Tchou,1 which waters Tibet for a distance of fifteen hundred kilometres, flowing along the northern base of the Himalayas, and to find out at last whether this river joins itself to the Brahmaputra in the northeast of Assam. The gold medal, My Lord, is promised to the traveller who will succeed in ascertaining a fact which is one of the greatest desiderata to the geography of India.”

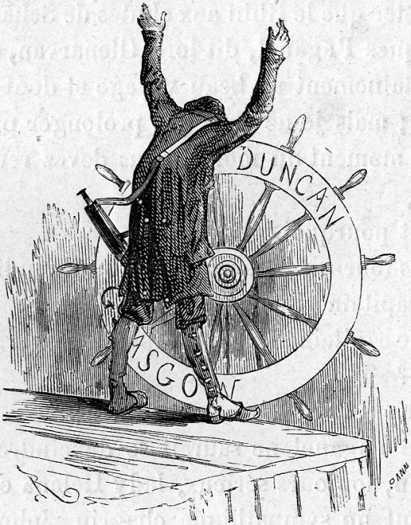

Paganel spoke with superb animation

Paganel was magnificent. He spoke with superb animation, soaring away on the wings of imagination. It would have been as impossible to stop him as to stop the Rhine at Schaffhausen Falls.

“Monsieur Jacques Paganel,” said Lord Glenarvan, after a brief pause, “that would certainly be a grand achievement, and you would confer a great boon on science, but I should not like to allow you to be labouring under a mistake any longer, and I must tell you, therefore, that for the present at least, you must give up the pleasure of a visit to India.”

“Give it up. And why?”

“Because you are turning your back on the Indian peninsula.”

“What? Captain Burton!”

“I am not Captain Burton,” said John Mangles.

“But the Scotia.”

“This ship is not the Scotia.”

It would be impossible to depict the astonishment of Paganel. He stared first at one and then at another in the utmost bewilderment.

Lord Glenarvan was perfectly grave, and Lady Helena’s and Mary’s expressions showed their sympathy for his vexation. As for John Mangles, he could not suppress a smile; but the Major appeared as unconcerned as usual. At last the poor fellow shrugged his shoulders, pushed down his spectacles over his nose and said:

“The Duncan! The Duncan!” he exclaimed, with a cry of despair

“You are joking.”

But just at that very moment his eye fell on the wheel of the ship, and he saw the two highlighted words on it:

Duncan

Glasgow

“The Duncan! The Duncan!” he exclaimed, with a cry of despair, and rushed down the stairs, and away to his cabin.

As soon as the unfortunate scientist had disappeared, everyone, except the Major, broke out into such peals of laughter that the sound reached the ears of the sailors in the forecastle. To mistake a railway and to take the train to Edinburgh when you wanted to go to Dumbarton might happen; but to mistake a ship and be sailing for Chile when you meant to go to India — that is a blunder indeed!

Paganel rushed down the stairs to his cabin

“However,” said Lord Glenarvan, “I am not much astonished at it in Paganel. He is quite famous for such misadventures. One day he published a celebrated map of America, and put Japan in it! But for all that, he is a distinguished scientist, and one of the best geographers in France.”

“But what shall we do with the poor gentleman?” said Lady Helena; “we can’t take him with us to Patagonia.”

“Why not?” said MacNabbs, gravely. “We are not responsible for his distraction. Suppose he were in a railway train, would they stop it for him?”

“No, but he could get out at the next station.”

“Well,” said Glenarvan. “That is just what he can do here, too, if he likes; he can disembark at the first place we land.”

Paganel, pitiful and ashamed, was coming back up onto the quarterdeck. He had been making sure that his luggage was all on board, and kept repeating incessantly the unlucky words, “The Duncan! the Duncan!” He could find no others in his vocabulary. He paced restlessly up and down; sometimes stopping to examine the mast, or gaze inquiringly at the mute horizon of the open sea.

Finally he returned to Lord Glenarvan. “And this Duncan — where is she going?”

“To America, Monsieur Paganel.”

“And to what particular part?”

“To Concepción.”

“In Chile! In Chile!” cried the unfortunate geographer. “And my mission to India. But what will M. de Quatrefages, the President of the Central Committee, say? And M. d’ Avezac? And M. Cortanbert? And M. Vivien de Saint Martin? How shall I show my face at the meetings of the Society?”

“Come, Monsieur Paganel, don’t despair. It can all be managed; you will only have to put up with a little delay. The Yarou-Dzangbo-Tchou will wait for you still in the mountains of Tibet. We shall soon put in at Madeira, and you will get a ship there to take you back to Europe.”

“Thank you, My Lord. I suppose I must resign myself to it; but people will say it is a most extraordinary adventure, and it is only to me such things happen. And then, too, there is a cabin taken for me on board the Scotia.”

“As to the Scotia, you’ll have to give that up.”

“But the Duncan is a pleasure yacht, is it not?” began Paganel again, after a fresh examination of the ship.

“Yes, sir,” said John Mangles, “and she belongs to Lord Glenarvan.”

“Who begs you to draw freely on his hospitality,” said Lord Glenarvan.

“A thousand thanks, My Lord! I deeply feel your courtesy, but allow me to make one observation: India is a fine country, and can offer many a surprising marvel to travellers. These ladies, I suppose, have never seen it. Well now, the man at the helm has only to give a turn at the wheel, and the Duncan will sail as easily to Calcutta as to Concepción; and since it is only a pleasure trip that you are—”

His proposal was met by such grave, disapproving shakes of the head, that he stopped short before the sentence was completed.

“Monsieur Paganel,” said Lady Helena. “If we were only on a pleasure trip, I should reply, ‘Let us all go to India together,’ and I am sure Lord Glenarvan would not object; but the Duncan is going to bring back shipwrecked mariners who were castaway on the shores of Patagonia, and we could not alter such a destination.”

In a few minutes the French traveller was made aware of the situation; he learned, not without emotion, of the providential discovery of the documents, the story of Captain Grant, and the generous proposal of Lady Helena.

“Madame, permit me to express my admiration of your conduct throughout,” he said. “My unreserved admiration. Let your yacht continue her course. I should reproach myself were I to cause a single day’s delay.”

“Will you join us in our search, then?” asked Lady Helena.

“It is impossible, Madame. I must fulfill my mission. I shall disembark at the first place you touch at, wherever it may be.”

“That will be Madeira,” said John Mangles.

“Madeira be it then. I shall only be 180 leagues from Lisbon, and I shall wait there for some means of transport.”

“Very well, Monsieur Paganel, it shall be as you wish; and, for my own part, I am very glad to be able to offer you, meantime, a few days’ hospitality. I only hope you will not find our company too dull.”

“Oh, My Lord,” exclaimed Paganel, “I am but too happy to have made a mistake which has turned out so agreeably. Still, it is a very ridiculous plight for a man to be in: to find himself sailing to America when he set out to go to the East Indies!”

But in spite of this melancholy reflection, the Frenchman submitted gracefully to the compulsory delay. He made himself amiable and merry, and even diverting, and enchanted the ladies with his good humour. Before the end of the day he was friends with everybody. At his request, the famous document was brought out. He studied it carefully and minutely for a long time, and finally declared his opinion that no other interpretation of it was possible. Mary Grant and her brother inspired a keen interest in him. He gave them great hope; indeed, the young girl could not help smiling at his sanguine prediction of success, and his odd way of foreseeing future events. But for his mission, he would surely have joined in the search for Captain Grant!

As for Lady Helena, when he heard that she was William Tuffnell’s daughter, there was an explosion of admiring epithets. He had known her father, and many letters had passed between them when William Tuffnell was a corresponding member of the Society! It was he himself that had introduced him and M. Malte Brun. What a meeting this was, and what a pleasure to travel with William Tuffnell’s daughter.

He wound up asking permission to kiss her, which Lady Helena granted, though it was, perhaps, a little improper.

1. What Paganel calls the Yarou-Dzangbo-Tchou is the Yarlung Tsangpo River of Tibet, and it is indeed the same river as the Brahmaputra. That they were the same river wasn’t settled until 1913, so Paganel’s hopes to prove this might have been overambitious. The largest waterfall on the river wasn’t seen by westerners until 1998. (Though the Chinese authorities claim to have photographed it from a helicopter in 1987.)