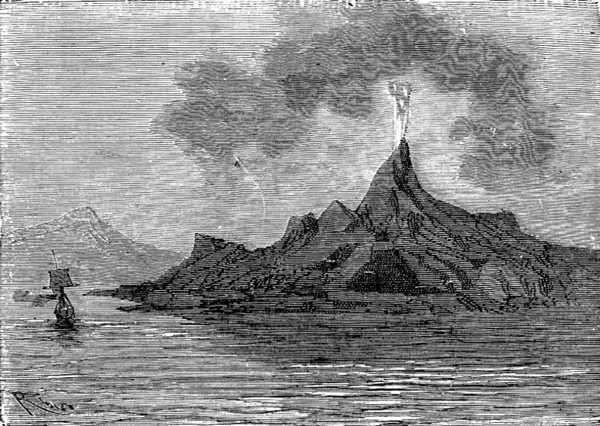

Tenerife

The Duncan, favoured by the currents from the north of Africa, was making rapid progress toward the Equator. On the 30th of August they sighted the Madeira group of islands, and Glenarvan, true to his promise, offered to put in there, and land his guest.

“My dear Lord,” said Paganel. “I won’t stand on ceremony with you. Tell me, did you intend to stop at Madeira before I came on board?”

“No,” said Glenarvan.

“Well, then, allow me to profit by my unlucky mistake. Madeira is an island too well known to be of much interest now to a geographer. Everything about this group of islands has been said and written already. Besides, the place is going completely down hill as far as viticulture is concerned. Just imagine, there are hardly any vineyards remaining in Madeira! In 1813, 22,000 pipes1 of wine were made there, and in 1845 the number fell to 2,669. It is a grievous spectacle! If it is all the same to you, we might go on to the Canary Isles instead.”

“We can easily stop in the Canaries instead,” said Glenarvan. “It will not the least interfere with our route.”

“I know it will not, my dear Lord. In the Canary Islands, you see, there are three groups of islands to study, besides the Peak of Tenerife, which I always wished to visit. This is an opportunity, and I should like to avail myself of it, and make the ascent of the famous mountain while I am waiting for a ship to take me back to Europe.”

“As you please, my dear Paganel,” said Lord Glenarvan, with a smile.

The Canary Islands are not far from Madeira, scarcely 250 miles2, a trifling distance for as swift a ship as the Duncan. Next day, on the 31st of October, about two p.m., John Mangles and Paganel were walking on the poop. The Frenchman was assailing his companion with all sorts of questions about Chile, when the captain interrupted him, and pointed toward the southern horizon.

“Monsieur Paganel?” he said.

“Yes, my dear Captain.”

“Be so good as to look in this direction. Do you see anything?”

“Nothing.”

“You’re not looking in the right place. It is not on the horizon, but above it in the clouds.”

“In the clouds? What am I looking for?”

“There, there, by the upper end of the bowsprit.”

“I see nothing.”

“Then you don’t want to see. Yet I tell you that the Peak of Tenerife is quite visible above the horizon, though we are forty miles off.”

But whether Paganel could not or would not see it then, two hours later he was forced to yield to the evidence of his eyes, or declare himself blind.

“You do see it at last, then,” said John Mangles.

“Yes, yes, distinctly,” said Paganel, adding in a disdainful tone, “and that’s what they call the Peak of Tenerife?”

“That’s the Peak.”

“It doesn’t look all that high.”

“It is 11,000 feet, though, above sea level.”

“That is not as tall as Mont Blanc.”

“That’s true, but when it comes to climbing it, you’ll probably think it’s high enough.”

Tenerife

“Climb it? Climb it? My dear Captain, what would be the good in that after Humboldt and Bonpland? That Humboldt was a great genius. He climbed this mountain, and his description of it leaves nothing to be desired. He tells us that it comprises five different zones — the vine zone, the laurel zone, the pine zone, the alpine heath zone, and, lastly, the sterile zone. He set his foot on the summit, and found that there was not even enough room to sit down. The view from the summit was very extensive, stretching over an area equal to Spain. Then he went right down into the volcano, and examined the extinct crater. What could I do, I should like you to tell me, after that great man?”

“Well, certainly, there isn’t much left to glean. That is unfortunate, too, for you would find it dull work waiting for a ship in the port of Tenerife. There isn’t much distraction here.”

“Except mine,” laughed Paganel. “But, I say, my dear Mangles, are there no ports in the Cape Verde Islands that we might touch at?”

“Oh, yes, nothing would be easier than putting you off at Villa Praia.”

“And then I should have an additional advantage, which is by no means inconsiderable — Cape Verde is not far from Senegal, where I should find some compatriots. I am quite aware that the islands are said to be devoid of much interest, and wild, and unhealthy; but everything is curious in the eyes of a geographer. Seeing is a science. There are people who do not know how to use their eyes, and who travel about with as much intelligence as a shell-fish. But that’s not in my line, I assure you.”

“As you please, Monsieur Paganel. I have no doubt geographical science will gain by your sojourn in the Cape Verde Islands. We must stop there anyway for coal, so your disembarkation will not occasion the least delay.”

The captain gave immediate orders for the yacht to continue her course, steering to the west of the Canary group, and leaving Tenerife on her larboard. She made rapid progress, and crossed the Tropic of Cancer on September 2nd at five o’clock in the morning.

The weather began to change, and the air became damp and heavy. It was the rainy season, “le tempo das aguas,” as the Spanish call it, a difficult season for travellers, but useful to the inhabitants of the African Islands, which lack trees, and consequently water. The rough weather prevented the passengers from going on deck, but did not make the conversation any less animated in the saloon.

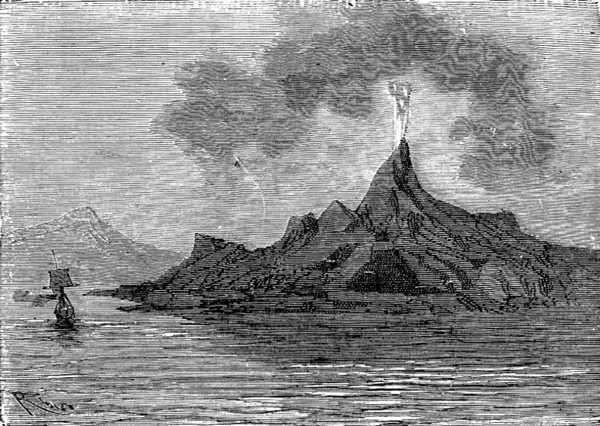

The appearance of the island through the thick veil of rain was mournful in the extreme

On September 3rd Paganel began to collect his luggage in preparation for his departure. The Duncan was already steaming among the Cape Verde Islands. She passed the Isle of Salt, a flat wasteland of sand, and salt ponds, infertile and desolate; she went on among the vast coral reefs and passed along side the Isle of St. Jacques, with its long north-south chain of basaltic mountains, until she entered the port of Villa Praia and anchored in eight fathoms of water. The weather was frightful, and the surf high, though the bay was sheltered from the sea winds. The rain fell in such torrents that the town was scarcely visible through it. It lay on a rising series of plateaus of volcanic rocks three hundred feet high. The appearance of the island through the thick veil of rain was mournful in the extreme.

Lady Helena could not go on shore as she had planned; indeed, even coaling was a difficult business, and the passengers had to content themselves below the decks as best they could. Naturally enough, the main topic of conversation was the weather. Everybody had something to say about it except the Major, who surveyed the universal deluge with the utmost indifference. Paganel walked up and down shaking his head.

“It is clear enough, Paganel,” said Lord Glenarvan, “that the elements are against you.”

“I’ll be all right,” said the Frenchman.

“You could not face rain like that, Monsieur Paganel,” said Lady Helena.

“Oh, I can face it, Madame. It is my luggage and instruments that I am worried about. Everything will be ruined.”

“The disembarking is the worst part of the business. Once at Villa Praia you might manage to find pretty good quarters. They wouldn’t be over clean, and you might find the monkeys and pigs not always the most agreeable companions. But travellers can not be too particular, and, moreover, in seven or eight months you would get a ship, I dare say, to take you back to Europe.”

“Seven or eight months!” exclaimed Paganel.

“At least. The Cape Verde Islands are not much frequented by ships during the rainy season. But you can employ your time usefully. This archipelago is still but little known. There’s still a lot of work to do in topography, climatology, ethnography, hypsometry…”

“You can explore the large rivers,” suggested Lady Helena.

“There are none, Madame.”

“Well, then, the small rivers.”

“There are none of those, either.”

“Brooks, then?”

“Pas davantage.”

“You can console yourself with the forests if that’s the case,” put in the Major.

“You can’t make forests without trees, and there are no trees.”

“A charming country!” said the Major.

“Comfort yourself, my dear Paganel, you’ll have the mountains at any rate,” said Glenarvan.

“Oh, they are neither lofty nor interesting, My Lord, and they have been described already.”

“Already!” said Lord Glenarvan.

“Yes, that is always my luck. At the Canary Islands, I saw myself anticipated by Humboldt, and here by M. Charles Sainte-Claire Deville, a geologist.”

“Impossible!”

“It is too true,” replied Paganel, in a doleful voice. “Monsieur Deville was on board the government corvette, La Décidée, when she touched at the Cape Verde Islands, and he explored the most interesting of the group, and went to the top of the volcano in Isle Fogo. What is left for me to do after him?”

“It is really a great pity,” said Helena. “What will become of you, Monsieur Paganel?”

Paganel remained silent.

“You would certainly have done much better to have landed at Madeira, even if there was no more wine,” said Glenarvan.

Still the learned secretary of the Society of Geography was silent.

“I’ll wait.”

“I’ll wait,” said the Major, exactly as if he’d said “I won’t wait.”

Paganel remained silent for several more seconds. “My dear Glenarvan, where do you mean to touch next?”

“At Concepción.”

“Diable! That is a long way out of my way to India.”

“Not really. From the moment you pass Cape Horn, you are getting closer to it.”

“I guess so.”

“Beside,” continued Lord Glenarvan, perfectly seriously, “when you are going to the Indies it doesn’t much matter much whether it is to the East or West.”

“What? It does too matter!”

“Not to mention the inhabitants of the Pampas in Patagonia are as much Indians as the natives of the Punjab.”

“Well done, My Lord,” said Paganel. “That’s a reason that would never have entered my head!”

“And then, my dear Paganel, you can gain the gold medal anyway. There is as much to be done, and sought, and investigated, and discovered in the Cordilleras of the Andes as in the mountains of Tibet.”

“But the course of the Yarou-Dzangbo-Tchou — what about that?”

“Go up the Rio Colorado instead. It is a river but little known, and its course on the map is marked out too much according to the fancy of geographers.”

“I know it is, my dear Lord. They have made grave mistakes. Oh, I have no question that the Geographical Society would have sent me to Patagonia as soon as to India, if I had sent in a request to that effect. But I never thought of it.”

“Just like you.”

“Come, Monsieur Paganel, will you go with us?” asked Lady Helena, in her most winning tone.

“Madame, and my mission?”

“I must tell you, we shall pass through the Straits of Magellan,” said Lord Glenarvan.

“My Lord, you are a tempter.”

“Let me add, that we shall visit Port Famine.”

“Port Famine!” exclaimed the Frenchman, besieged on all sides. “That port celebrated in geographical splendour!”

“Think, too, Monsieur Paganel, that by taking part in our enterprise, you will be forging bonds between France with Scotland,” said Lady Helena.

“Undoubtedly.”

“A geographer would be of much use to our expedition, and what can be nobler than to bring science to the service of humanity?”

“That’s well said, Madame.”

“Take my advice, then, and yield to chance, or rather Providence. Follow our example. Providence sent us the document, and we set sail. Providence brought you on board the Duncan. Don’t leave her.”

“Shall I say yes, my good friends? Come, now, tell me. You want me very much to stay, don’t you?” said Paganel.

“And you’re dying to stay, now, aren’t you, Paganel?” returned Glenarvan.

“Parbleu!” exclaimed the learned geographer, “but I was afraid of being indiscreet!”

1. One pipe is approximately 500 litres. (About 125 gallons — DAS)

2. About 90 leagues. (360 kilometres — DAS)