The Duncan at sea

Everyone aboard the Duncan was overjoyed to learn of Paganel’s decision. Young Robert threw himself on the Secretary to hug him with enough force that he nearly knocked Paganel over. “He’s a tough petit bonhomme,” said Paganel. “I’ll teach him geography.”

Robert was bound to become an accomplished gentleman some day, for John Mangles was making a sailor of him, the Major was teaching him self control, and Lord and Lady Glenarvan were instilling him with courage, goodness and generosity, while Mary was inspiring him with gratitude toward his instructors.

The Duncan soon finished taking on coal, and turned her back on the dismal region. She was soon in the current flowing down the coast of Brazil, and on the 7th of September entered the southern hemisphere.

So far, the crossing had been uneventful. Everyone was hopeful for the success of their mission, and each day their faith in finding Captain Grant grew. Captain Mangles was among the most confident on board, but his confidence mainly arose from the desire he had to see Miss Mary happy. He was quite smitten with this young girl, and managed to conceal his sentiments so well that everyone on board the Duncan saw it — except himself and Mary Grant.

The Duncan at sea

As for the learned geographer, he was probably the happiest man in all the southern hemisphere. He spent whole days in studying maps which were spread out on the saloon table — to the great annoyance of Mr. Olbinett who could never get the cloth laid for meals without disputes on the subject. But all the passengers took Paganel’s side except the Major, who was perfectly indifferent about geographical questions, especially at dinner-time. Paganel also came across a trove of old books in the mate’s chest that included a number of Spanish volumes. He determined forthwith to teach himself the language of Cervantes, as no one on board understood it, and it would be helpful in their search along the Chilean coast. Thanks to his talent for languages, he expected to be able to speak the language fluently when they arrived at Concepción. He studied it diligently, and was constantly muttering heterogeneous syllables to himself.

He spent his spare time teaching young Robert, and instructing him in the history of the country they were so rapidly approaching.

On the 10th of September, at latitude 5° 37‘ and longitude 31° 15′, Lord Glenarvan learned something that many more educated people probably do not know. Paganel told the story of America, and the great navigators in whose path the Duncan now followed. He went back to Christopher Columbus, and how he had gone to his grave without ever knowing that he had discovered a New World.

His whole audience was surprised, but Paganel persisted in his contention.

“Nothing is more certain,” he said. “I do not wish to diminish the glory of Columbus, but the fact is certain. At the end of the fifteenth century everyone had the same objective: to facilitate communication with Asia. In a word, go by the shortest route to “Spice Country.” That is what Columbus tried to do: to seek the East by sailing West. He made four journeys. He touched the coasts of America at Cumaná1, Honduras, Mosquitos, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama, which he took for the lands of Japan and China. He died without having realized that he had discovered a great continent to which he should have bequeathed his name!”

“I want to believe you, my dear Paganel,” said Glenarvan, “however, you will allow me to be surprised, and to ask you who are the navigators who did learn the truth about the discoveries of Columbus?”

“His successors, Ojeda, who had already accompanied him in his travels, as well as Vincent Pinzon, Vespucci, Mendoza, Bastidas, Cabral, Solis, and Balboa. These navigators skirted the eastern coasts of America. They mapped them, three hundred and sixty years ago, moving southward, carried by the same current that carries us along! My friends, we crossed the Equator at the very spot where Pinzon crossed it in the last year of the fifteenth century, and we are approaching that eighth degree of southern latitude where he landed in Brazil. A year later, Cabral of Portugal reached the port of Seguro. Then Vespucius, in his third expedition in 1502, went farther south. In 1508, Vincent Pinzon and Solis joined forces for the mapping of the American shores, and in 1514, Solis discovered the mouth of the Rio de la Plata, where he was devoured by the natives, leaving Magellan the glory of rounding the continent. This great navigator set out with five ships in 1519, followed the coast of Patagonia, discovered the ports of Desire, and San Julian, where he had a long rest, found at fifty-two degrees of latitude, Cape Virgenes at the mouth of this strait that bears his name, and on the 28th of November, 1520, he emerged into the Pacific Ocean. Ah! what a joy he must have felt, and how his heart must have beat, when he saw a new sea sparkle on the horizon beneath the rays of the sun!”

“Yes, Mr. Paganel!” said Robert Grant, excited by the words of the geographer. “I would have liked to be there!”

“Me too, my boy, and I would not have missed such an opportunity, if Heaven had given birth to me three hundred years ago!”

“That would have been unfortunate for us, Mr. Paganel,” said Lady Helena, “for you would not be on the Duncan’s poop now to tell us this story.”

“Another would have said it in my place, Madame, and he would have added that the mapping of the west coast is due to the brothers Pizarro. Those bold adventurers were great founders of cities. Cusco, Quito, Lima, Santiago, Villarica, Valparaiso and Concepción, where the Duncan takes us, are their work. At that time, Pizarro’s discoveries were connected with those of Magellan, and the complete American coast appeared on the maps, much to the satisfaction of the old world’s scientists.”

“Well,” said Robert, “I would not have been satisfied yet.”

“Why is that?” asked Mary, looking at her younger brother, who was passionately hanging on every word of this tale of discoveries.

“Yes, my boy. Why?” asked Lord Glenarvan with the most encouraging smile.

“Because I’d want to know what was beyond the Strait of Magellan.”

“Bravo, my friend,” said Paganel, “and I too would have liked to know whether the continent extended to the pole, or whether there was a free sea, as Drake supposed — one of your compatriots, My Lord. It is therefore obvious that if Robert Grant and Jacques Paganel had lived in the seventeenth century, they would have followed Shouten and Lemaire, two Dutch explorers eager to solve this geographic enigma.

“Were they scientists?” asked Lady Helena.

“No, but daring traders, who cared little for the scientific side of their discoveries. At the time, the Dutch East Indian company had an absolute monopoly over all the trade through the Straits of Magellan. Since no other passage was yet known to reach Asia by travelling West, this monopoly gave them enormous profit. Some merchants wished to thwart this monopoly by discovering another strait. One of these men was Isaac Lemaire, an intelligent and educated man. He paid for an expedition commanded by his nephew, Jacob Lemaire, and Shouten, an experienced sailor from Horn. These bold navigators set out in June 1615, nearly a century after Magellan; they discovered the strait of Lemaire, between Tierra del Fuego and the Staten Island,2 and on February 12, 1616, they doubled that famous Cape Horn, which, even more than its brother, the Cape of Good Hope, would have deserved to be called ‘The Cape of Storms!’”

“Oh, I would have liked to be there!” said Robert.

“And you would have experienced the greatest satisfaction, my boy,” said Paganel, becoming more animated. “Is there, in fact, a truer satisfaction, a pleasure more real than that of the navigator who adds his own discoveries to the map? He sees a land gradually forming under his gaze, island by island, promontory by promontory, and, so to speak, emerging from the bosom of the waves! First, the outlines are vague, broken, interrupted! Here a solitary cape, there an isolated bay, further a gulf of unknown breadth. Slowly the discoveries come together, the lines meet, the dotted lines of guesswork give way to the solid lines of fact. The bare bones are fleshed out by the indentations of the bays; the capes attach to fixed shores; until, finally, the new continent with its lakes, rivers, mountains, valleys and plains; villages, towns and capitals; is spread out on the globe in all its magnificent splendour! Ah! my friends, a discoverer of land is a real inventor! He has the greatest joy and wonder! But now this mine is almost exhausted! We have seen everything, identified everything, invented the continents or new worlds, and we, the latest ones come in geographical science, have we nothing more to do?”

“Yes, my dear Paganel,” replied Glenarvan.

“What?”

“What we do!”

The Duncan, continued in the course of Vespucci and Magellan with marvellous speed. On September 15, she crossed the tropic of Capricorn, and the course was set for the entrance of the famous strait. Several times the lower coasts of Patagonia were seen as a barely visible line on the horizon, more than ten miles away, and Paganel’s famous telescope gave him only a vague idea of these American shores.

On the 25th of September, the Duncan arrived off the Straits of Magellan, and entered them without delay. This route is generally preferred by steamers on their way to the Pacific Ocean. The exact length of the straits is 376 miles.3 Ships of the largest tonnage find sufficient water depth throughout, even close to the shore. There is a good bottom everywhere, an abundance of fresh water, rivers abounding in fish, forests in game, and plenty of safe and accessible harbours. In fact a thousand things that are lacking in Lemaire Strait and Cape Horn, with its terrible rocks, incessantly visited by hurricanes and tempests.

For the first few hours, that is, sixty to eighty miles — as far as Cape Gregory — the coasts were low and sandy. Jacques Paganel did not want to miss a single view, nor a single detail of the straits. The passage would take thirty-six hours, and the moving panorama on both sides, seen in all the clearness and glory of the light of a southern sun, was well worth the trouble of looking at and admiring. On the Terra del Fuego side, a few wretched-looking people were wandering about on the rocks, but on the other side not a solitary inhabitant was visible.

Paganel was so disappointed at not being able to catch a glimpse of any Patagonians, that his companions were quite amused by him. He would insist that a Patagonia without Patagonians was not a Patagonia at all.

“Patience, my worthy geographer,” said Lord Glenarvan. “We shall see the Patagonians yet.”

“I am not sure of it.”

“But there are such a people,” said Lady Helena.

“I greatly doubt it, Madame, since I don’t see them.”

“But surely the very name of Patagonia, which means ‘big feet’ in Spanish, would not have been given to imaginary beings.”

“Oh, the name doesn’t have anything to do with it,” said Paganel, who was arguing simply for the sake of arguing. “And besides, to speak the truth, we are not sure if that is their name.”

“What an idea!” said Glenarvan. “Did you know that, Major?”

“No. And I wouldn’t give a Scotch pound-note for the information.”

“You shall hear it, however, Major Indifferent,” said Paganel. “Though Magellan called the natives of this country Patagonians, the Fuegians called them ‘Tiremenen,’ the Chileans ‘Caucalhues,’ the colonists of Carmen ‘Tehuelches,’ the Araucans ‘Huiliches’; Bougainville gives them the name of ‘Chauha,’ and Falkner that of ‘Tehuelhets’. The name they give themselves is ‘Inaken’. Now, tell me, how would you identify them? Indeed, is it likely that a people with so many names has any actual existence?”

“That’s a queer argument, certainly,” said Lady Helena.

“I’ll admit that,” said her husband, “but our friend Paganel must also admit that even if there are doubts about the name of the Patagonians, there is none about their size.”

“Indeed, I will never admit to anything as outrageous as that,” replied Paganel.

“They are tall,” said Glenarvan.

“I don’t know.”

“Small?” asked Lady Helena.

“No one can say.”

“About average, then?” said MacNabbs, looking for a compromise.

“I don’t know that either.”

“That’s going a little too far,” said Glenarvan. “Travellers who have seen them—”

“Travellers who have seen them,” interrupted Paganel, “don’t agree at all in their accounts. Magellan said that his head scarcely reached to their waist.”

“Well, that proves—”

“Yes, but Drake declares that the English are taller than the tallest Patagonian!”

“About what I’d expect from an Englishman,” said the Major, disdainfully, “but what would a Scot say?”

“Cavendish assures us that they are tall and robust,” said Paganel. “Hawkins makes out that they are giants. Lemaire and Shouten declare that they are eleven feet tall.”

“These are all credible witnesses,” said Glenarvan.

“Yes, quite as much as Wood, Narborough, and Falkner, who say they are of medium stature. Again, Byron, Giraudais, Bougainville, Wallis, and Carteret, declared that the Patagonians are six feet six inches tall while M. d’Orbigny, the scholar who knows these lands best, gives them an average height of five feet four inches.”

“But what is the truth, then, among all these contradictions?” asked Lady Helena.

“Just this, Madame; the Patagonians have short legs, and a large trunk; or by way of a joke we might say that these natives are six feet tall when they are sitting, and only five when they are standing.”

“Bravo! My dear geographer,” said Glenarvan. “That is very well put.”

“Unless the race has no existence: that would reconcile all statements,” said Paganel. “But here is one consolation, in any event: the Straits of Magellan are very magnificent, even without Patagonians.”

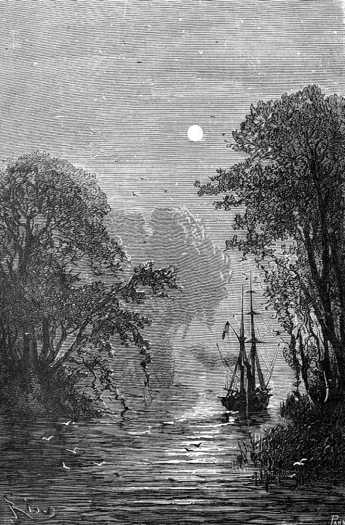

Often the end of Duncan’s yards grazed the branches of the Antarctic beeches leaning over the waves

The Duncan was rounding the peninsula of Brunswick between splendid panoramas. Seventy miles after doubling Cape Gregory, she passed the penitentiary of Punta Arena on her starboard. The church steeple and the Chilean flag gleamed for an instant among the trees, and then the strait wound on between huge granitic masses which had an imposing effect. Cloud-capped mountains appeared, their heads white with eternal snows, and their feet hidden in immense forests. Toward the southwest, Mount Tarn rose 6,500 feet high. Night came on after a long lingering twilight — the light imperceptibly melting away into soft shades.

The sky glittered with brilliant stars, and the Southern Cross pointed the way for navigators seeking the south pole. In the midst of this luminous darkness, in the light of these stars which replace the lighthouses of the civilized coast, the yacht continued its course audaciously, without anchoring in any of the easy bays that abound on this shore. She continued her course fearlessly through the luminous darkness. Often the end of her yards grazed the branches of the Antarctic beeches leaning over the waves. Her screw beat the waters of the great rivers, waking geese, ducks, snipe, and teal.

Presently ruins came in sight, crumbling buildings, which the night invested with grandeur: the sad remains of a deserted settlement, whose name will be an eternal protest against these fertile shores and forests full of game. The Duncan was passing Port Famine.

Port Famine

It was on this site that the Spaniard Sarmiento, in 1584, settled with three hundred immigrants. He founded the settlement of Rey Don Felipe, but the extreme severity of the winters decimated the colony, and those who had survived through the cold died subsequently of starvation. The English privateer Thomas Cavendish landed at the site in 1587, and found only ruins. He named the site Port Famine.4

The Duncan sailed past these deserted shores, and at daybreak entered a series of narrow channels. She sailed between forests of beech, ash, and birch from which emerged green domes of foothills carpeted with vigorous holly. Sharp crags, Buckland’s Obelisk the tallest among them, rose above the hills. She passed the bay of St. Nicholas, formerly French Bay, so named by Bougainville. In the distance, herds of seals and pods of large whales played. Their spouts could be seen from four miles away. At length the Duncan doubled Cape Froward, still bristling with the ice of the last winter. On the other side of the strait, in Terra del Fuego, stood Mount Sarmiento, towering to a height of 6,000 feet: an enormous accumulation of rocks, separated by bands of cloud, forming a sort of aerial archipelago. Cape Froward is the true southern tip of the American continent, for Cape Horn is nothing but a rock lost at sea at a latitude of 52°.

Beyond Cape Froward, the strait narrowed between Brunswick Peninsula and Desolation Island: a long island lying between a thousand islets, like a huge cetacean beached upon of the rocks. What a contrast between this jagged end of America and the sharp peaks of Africa, Australia or India! What unknown cataclysm had pulverized this immense promontory thrown up between two oceans?

These fertile shores gave way to a series of barren coasts, wild-looking, indented by the thousand fjords of this labyrinth. The Duncan, without error or hesitation, followed a sinuous course, mixing the eddies of her smoke with the mists churned by the rocks. She passed, without slowing, before some Spanish factories established on these abandoned banks. The strait widened at Cape Tamar. At last, thirty-six hours after entering the strait, she saw the rock of Cape Pilares appear on the western extremity of Desolation Island. An immense, free, sparkling sea stretched out before her bow, and Jacques Paganel greeted her with an enthusiastic gesture, felt himself as moved as Ferdinand Magellan himself, at the moment when the Trinidad5 sailed into the breezes of the Pacific Ocean.

1. Venezuela — DAS

2. Named after the Netherlands States-General, just like the New York borough. Now part of Argentina, and known as Isla de los Estados — DAS

3. 130 leagues, 520 kilometres

4. Verne has the settlement founded in 1581, and Cavendish finding one survivor — DAS

5. The ship that carried Magellan