Concepción

Eight days after they had doubled Cape Pilares, the Duncan steamed into the Talcahuano Bay, a magnificent estuary, twelve miles long and nine broad. The weather was splendid. The skies of this country are cloudless from November to March, and the southerly wind invariably reigns along the coast sheltered by the Andean range. Following Lord Glenarvan’s orders, John Mangles had sailed as closely to the Chiloé Archipelago as possible, and examined all the inlets and windings of the coast, hoping to discover some traces of the shipwreck. A broken spar, or a piece of wood worked by the hands of men could have put them on the right track, but they found nothing, and the Duncan continued on her way, until she dropped anchor at the port of Talcahuano, forty-two days after leaving the misty waters of the Clyde.

Glenarvan had a boat lowered immediately, and accompanied by Paganel, landed at the foot of the pier. The learned geographer gladly availed himself of the opportunity to make use of the Spanish he had been studying so conscientiously, but to his astonishment, found he could not make himself understood by the natives.

“I don’t have the accent,” he said.

“Let’s go to Customs,” said Glenarvan.

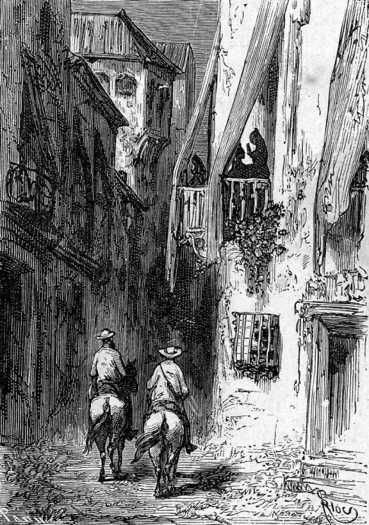

There, he learned by means of a few English words, aided by expressive gestures, that the British Consul lived at Concepción, an hour’s ride away. Glenarvan easily found two swift horses, and he and Paganel were soon within the walls of the great city, founded by the enterprising genius of Valdivia, the valiant comrade of the Pizarros. It had declined from its former splendour. Often pillaged by the natives, and burned in 1819, it lay in desolation and ruin, its walls still blackened by the flames. It scarcely numbering 8,000 inhabitants, now, and was overshadowed by Talcahuano. Grass was growing in the streets beneath the lazy feet of its citizens, and all trade and business, indeed any description of activity, was impossible. The notes of mandolins resounded from every balcony, and languid songs floated on the breeze. Concepción, the ancient city of men, had become a village of women and children.

Concepción

Lord Glenarvan was unwilling to inquire into the causes of this decay, though Paganel tried to draw him into a discussion on the subject, and without losing a moment he went to J. R. Bentock, Esq., Consul of her Britannic Majesty, who received them very courteously, and, on learning the story of Captain Grant, undertook to make inquiries all along the coast.

As to the question of whether the three-master Britannia had come to grief near the 37th parallel along the Chilean or Araucanían coast, he had no information. No report of such an event had reached the Consul, or any of his colleagues from other nations. Glenarvan was not discouraged; he went back to Talcahuano, and spared neither pains nor expense. He dispatched agents to make an examination of the coast. But it was all in vain. The most careful inquiries made among the neighbouring populations were fruitless, and Lord Glenarvan returned to the yacht to report his lack of success. It had to be concluded that the Britannia had left no trace of her shipwreck.

When Glenarvan told his companions of his failure to learn anything, Mary Grant and her brother could not restrain their grief. It was six days after the arrival of the Duncan at Talcahuano. The passengers were gathered on the poop. Lady Helena did her best to console them, not with words — What could she say? — but with hugs and caresses. Jacques Paganel took up the document and began studying it again, as if he wanted to snatch new secrets from it. He had been poring over it for more than an hour when Glenarvan interrupted him.

“Paganel! I appeal to your intelligence. Has our analysis of this document been wrong? Is there anything illogical about our interpretation?”

Paganel was silent, absorbed in reflection.

“Have we mistaken the place where the catastrophe occurred?” asked Glenarvan. “Does not the name Patagonia seem apparent even to the least clear-sighted individual?”

Paganel was still silent.

“Besides,” said Glenarvan, “does not the word Indian prove we are right?”

“Perfectly,” said MacNabbs.

“And is it not evident, then, that at the moment of writing the words, the shipwrecked men were expecting to be made prisoners by the Indians?”

“I wouldn’t go that far, my dear Lord,” said Paganel. “Even if your other conclusions are correct, that last one, at least, does not seem to be the only interpretation to me.”

“What do you mean?” asked Lady Helena, while all eyes were fixed on the geographer.

“I mean,” said Paganel, emphasizing his words, “that Captain Grant is now a prisoner of the Indians, and I further add that the document states it unmistakably.”

“Explain yourself, sir,” said Mary Grant.

“Nothing is plainer, dear Mary. Instead of reading the document ‘seront prisonniers’, read ‘sont prisonniers’, and the whole thing is clear.”

“But that’s impossible,” said Lord Glenarvan.

“Impossible? Why, my noble friend?” asked Paganel, smiling.

“Because the bottle could only have been thrown into the sea just when the vessel broke on the rocks, and consequently the latitude and longitude given refer to the actual place of the shipwreck.”

“There is no proof of that,” said Paganel, sharply. “And I see nothing to preclude the supposition that the poor fellows — after having been dragged by the Indians into the interior of the continent — sought to make known the place of their captivity by means of this bottle.”

“Except for the fact, my dear Paganel, that in order to throw a bottle into the sea, the sea must be there.”

“Or in the absence of the sea, a river which ran into it.”

An astonished silence greeted this unexpected, and yet reasonable, answer. The brightening of everyone’s eyes revealed the rekindling of their hope to Paganel. Lady Helena was the first to speak.

“What an idea!”

“And what a good idea,” added the geographer, naively.

“What would you advise, then?” said Glenarvan.

“My advice is to follow the 37th parallel from the point where it touches the American continent to where it dips into the Atlantic, without deviating from it half a degree, and possibly in some part of its course we shall find the shipwrecked from the Britannia.”

“There is a poor chance of that,” said the Major.

“Poor as it is,” said Paganel, “we must not neglect it. If I am right in my conjecture, that the bottle reached the sea on the current of some river, we cannot fail to fall on the path of the prisoners. You can easily convince yourselves of this by looking at this map of the country.”

He laid out a map of Chile and the Argentinian provinces on the table as he spoke.

“Just follow me across the American continent for a moment. Let us cross the narrow strip of Chile, and over the Andes mountains, and get into the heart of the Pampas. Will we find any lack of rivers, watercourses, or streams? No, for the Rio Negro, Rio Colorado, and their tributaries are intersected by the 37th parallel, and any of them might have carried the bottle on its waters. There, perhaps, in the midst of a tribe in some Indian settlement at the edge of some little-known river in the gorges of the mountains, those whom I may call my friends await some providential intervention. Ought we to disappoint their hopes? Do you not all agree with me that it is our duty to go along the line my finger is pointing out at this moment on the map? And if, against all odds, we find I have been mistaken, is it not then our duty to keep moving straight on, and follow the 37th parallel until we find those we seek, even if we go all around the world?”

His generous enthusiasm so touched his listeners that they involuntarily rose to their feet and came to shake his hands.

“Yes!” cried Robert, devouring the map with his eyes. “My father is there!”

“And wherever he is,” said Glenarvan, “we will find him. Nothing can be more logical than Paganel’s theory, and we must, without hesitation, follow the course he points out. Captain Grant may have fallen into the hands of a large tribe, or his captors may be but a handful. In the latter case we shall carry him off at once. If the former, after we have reconnoitred the situation, we will meet with the Duncan on the eastern coast and go to Buenos Aires, where we can soon organize a detachment of men, with Major MacNabbs at their head, strong enough to tackle all the Indians in the Argentinian provinces.”

“Hear, Hear, Your Honour!” said John Mangles, “And may I ask, will this crossing of the continent be without peril?”

“Without danger, or hardship,” said Paganel. “How many have already accomplished it, who had scarcely any resources, and whose courage was not supported by the grandeur of this enterprise! Did not Basilio Villarino go from Carmen to the Cordilleras in 1782? Didn’t Don Luiz de la Cruz, a Chilean alcalde of the province of Concepción, follow this 37th parallel across the Andes from Antuco to Buenos Aires in only forty days in 1806? Finally, have not Colonel Garcia, Mr. Alcide d’Orbigny, and my honourable colleague, Dr. Martin de Moussy, travelled this country in every direction, and done for science what we are going to do for humaneness?”

“Monsieur, Monsieur!” said Mary Grant in a voice broken with emotion. “How can you follow a vocation that exposes you to so many dangers?”

“Dangers!” exclaimed Paganel. “Who said anything about danger?”

“Not me!” said Robert Grant, his eyes wide and bright.

“Dangers!” scoffed Paganel, “They aren’t worth considering. A journey of three hundred and fifty leagues, in a straight line. A journey which will take place at a latitude similar to Spain, Sicily, or Greece in the other hemisphere and therefore in a climate almost identical. A trip whose duration will be a month at most! It’s a walk in the country!”

“Monsieur Paganel,” asked Lady Helena, “you have no fear then that if the poor fellows have fallen into the hands of the Indians their lives at least have been spared.”

“What a question? Why, Madame, the Indians are not cannibals! Far from it. One of my own countrymen, M. Guinnard, who I knew at the Geographical Society, was a prisoner among the Indians in the Pampas for three years. He suffered. He was badly treated, but came out victorious from his ordeal. A European is a useful being in these countries. The Indians know his value, and take care of him as if he were some prize animal.”

“There is no time for delay,” said Lord Glenarvan. “We must go, and as soon as possible. What route should we take?”

“One that is both easy and agreeable,” said Paganel. “It is rather mountainous at first, but then slopes gently down the eastern side of the Andes into a smooth plain, turfed and gravelled quite like a garden.”

“Let’s see the map,” said the Major.

“Here it is, my dear MacNabbs. We shall pick up the 37th parallel on the coast, between Rumena Point and Carnero Bay, pass through the capital of Araucanía, and cut through the mountains by Antuco Pass north of the volcano. Then gliding gently down the mountain sides, past the Rio Neuquén and the Rio Colorado we reach the Pampas, Lake Epecuén,1 the Guamini River, to the Sierra Tapalquen. There we shall reach the frontier of the province of Buenos Aires. This we shall cross, and pass over the Sierra Tandil, pursuing our search to the very shores of the Atlantic, as far as Point Medano.”

Paganel went through this itinerary for the expedition without so much as a glance at the map. He was so well informed in the travels of Frézier, Molina, Humboldt, Miers, and d’Orbigny, that he had the geographical nomenclature at his finger tips, and trusted implicitly to his never-failing memory.

“You see then, my dear friends,” he added, “that it is a straight road. In thirty days we shall have gone over it, and arrived on the eastern side to reunite with the Duncan, however much she may be delayed by the westerly winds.”

“Then the Duncan is to cruise between Cape Corrientes and Cape San Antonio,” said John Mangles.

“Just so.”

“And how is the expedition to be organized?” asked Glenarvan.

“As simply as possible. All there is to be done is to reconnoiter the situation of Captain Grant and not to fight with the Indians. I think that Lord Glenarvan, our natural leader; the Major, who would not yield his place to anybody; and your humble servant, Jacques Paganel—”

“And me!” said young Robert.

“Robert!” exclaimed Mary.

“Why not?” asked Paganel. “Travel shapes the young. We four, and three sailors from the Duncan.”

“And does your Your Honour mean to pass me by?” John Mangles asked Glenarvan.

“My dear John,” said Glenarvan, “we’re leaving the ladies on board, those dearer to me than life, and who is to watch over them but the Duncan’s devoted captain?”

“Then we can’t accompany you?” asked Lady Helena, while a shade of sadness clouded her eyes.

“My dear Helena, the journey must be accomplished with great speed. Our separation will be short.”

“Yes, dear, I understand. It’s all right; and I do hope you will succeed.”

“Besides, you can hardly call it a journey,” said Paganel.

“What is it, then?” asked Lady Helena

“A passage, nothing more. We will pass, like the honest man of the earth, doing as much good as possible. Transire beneficiendo shall be our motto.”

This ended the discussion, if a conversation can be so called, where all who take part in it are of the same opinion. Preparations commenced the same day, but as secretly as possible to prevent the Indians getting wind of it.

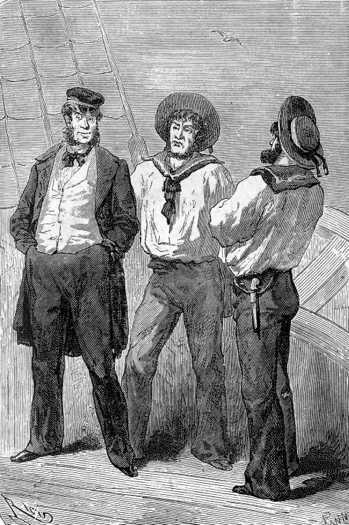

Tom Austin, Wilson, and Mulrady

The day of departure was set for the 14th of October. When it came to choosing the sailors to go with them, all volunteered, and Glenarvan was spoiled for choice. To prevent jealousy among the crew he chose the three to accompany him by lot. Fortune favoured the mate, Tom Austin; Wilson, a strong, jovial young fellow; and Mulrady, so good a boxer that he might have entered the lists with Tom Sayers2 himself.

Glenarvan had been very busy with the preparations, for he was anxious to be ready by the appointed day. John Mangles was equally busy in coaling and provisioning the ship, so she would be ready to put to sea as soon as the land party departed. He wanted to be the first to reach the Argentinian coast. The friendly rivalry between them benefitted them all.

On the 14th of October, at the appointed hour, everything was ready. The whole search party assembled in the saloon to bid farewell to those who remained behind. The Duncan was just about to get under way, and already the blades of her screw were agitating the limpid waters of Talcahuano. Glenarvan, Paganel, MacNabbs, Robert Grant, Tom Austin, Wilson, and Mulrady, stood armed with Colt rifles and revolvers. Guides and mules awaited them at the end of the pier.

“It is time,” said Lord Edward at last.

“Go then, dear Edward,” said Lady Helena, restraining her emotion.

Lord Glenarvan clasped her closely to his breast for an instant, and then turned away, while Robert flung his arms round Mary’s neck.

“And now, dear companions,” said Paganel, “a final handshake, to last us to the shores of the Atlantic!”

It was a lot to ask, but he certainly got strong enough grips and hugs to go some way toward satisfying his desire. They went up onto the deck, and the seven travellers left the Duncan. They were soon on the quay, and as the yacht came about to set course for the harbour channel, she came within half a cable of wharf.

Lady Helena called out “God help you, my friends!” one last time from the quarterdeck.

“And he will help us, Madame,” shouted Paganel in reply, “for you may be sure we will help ourselves.”

“All ahead!” the captain shouted to his engineer.

“On the way!” ordered Lord Glenarvan.

And as the travellers turned their mounts to follow the path along the shore, the Duncan, under the action of her screw, was heading out to sea.

1. Verne has “Salinas” here, but that is 500 miles (800 kilometres) north of Paganel’s projected route, and Lake Epecuén is right were he placed Salinas.

2. A famous boxer from London