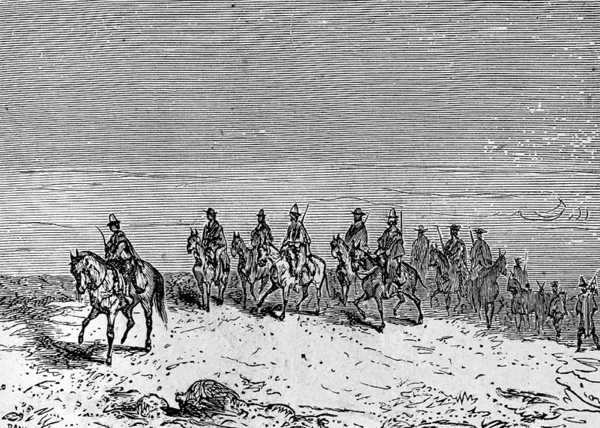

The madrina walked in front, leading the ten mules

The native troops organized by Lord Glenarvan consisted of three men and a boy. The captain of the muleteers was an Englishman, who had become naturalized through twenty years’ residence in the country. He made a livelihood by renting out mules to travellers, and leading them over the difficult passes of the Cordilleras, after which he put them in the charge of a baqueano, or Argentinian guide, familiar with the routes through the Pampas. This Englishman had not spent so much time among mules and Indians that he had forgotten his mother tongue, and this was fortunate as Lord Glenarvan found it far easier to pass his orders through him, if he wanted to see them carried out, than to rely on Paganel’s still imperfect grasp of the language.

The madrina walked in front, leading the ten mules

The catapez, as he was called in Chilean, had two native peons, and a boy about twelve years old under him. The peons took care of the baggage mules, and the boy led the madrina, a young mare adorned with rattles and bells, which walked in front, leading the ten mules. The travellers rode seven of these, and the catapez another. The remaining two mules carried provisions and a few bales of goods, intended to secure the goodwill of the caciques of the plain. The peons walked, as was their custom. Travelling in this manner was considered to be the quickest, and safest way to cross the continent.

Crossing the Andes is not a simple journey to undertake. It could not be accomplished without the help of the hardy mules of the famous Argentinian breed. These excellent animals are far superior to other breeds. They are not particular about their food, only drink once a day, and they can easily travel ten leagues in eight hours while carrying a load of fourteen arrobes1 without complaint.

There would be few inns along this road from one ocean to another. The travellers took provisions of dried meat, and rice seasoned with pimento, which they would supplement with such game as could be shot along the way. The torrents would provide them with water in the mountains, and the rivulets in the plains, which they improved by the addition of a few drops of rum. Each man carried a supply of this in a bullock’s horn, called a chiffle. They had to be careful, however, not to abuse alcoholic beverages, as the climate itself had a peculiarly exhilarating effect on the nervous system. Their saddles, called recado by the natives, also served as their bedding. This saddle is made of pelions — sheepskin, tanned on one side and woolly on the other — fastened by ornately embroidered straps. Wrapped in these warm coverings a traveller could sleep soundly, well protected on the damp nights.

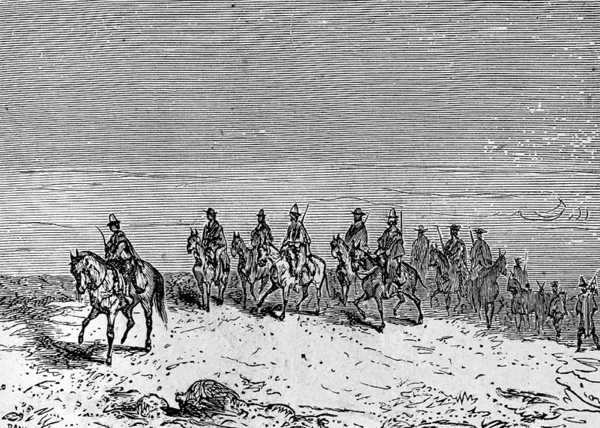

Robert and Paganel

Glenarvan was an experienced traveller, who knew how to adapt himself to the customs of other countries. He adopted the Chilean costume for himself and his whole party. Paganel and Robert, two children — one big and one small — were wild with delight as they inserted their heads in the national poncho, an immense tartan cloth with a hole in centre. Their legs were encased in high, colt leather boots. The mules were richly caparisoned, with Arabian bits in their mouths, and long reins of plaited leather, which also served as a whip; the headpiece of the bridle was decorated with metal ornaments, and each mule carried alforjas, double sacks of brightly coloured cloth, containing the day’s provisions.

Paganel, absent minded as usual, was nearly kicked three or four times by his excellent steed before he could mount it. But once in the saddle, his inseparable telescope hung on his baldric, he held on well enough: keeping his feet fast in the stirrups, and trusting entirely to the intelligence of his mule. As for young Robert, his first attempt at mounting was successful, and he showed that he had the makings of an excellent horseman.

The weather was splendid when they set out; the sky was a deep cloudless blue; the heat of the sun was moderated by refreshing sea breezes. They made their way quickly along the winding shore of Talcahuano Bay on their way to the parallel, thirty miles to the south. They spoke little as they passed through the reeds of old desiccated marshes. The farewells of their departure still a poignant memory. The smoke from the Duncan was still visible on the horizon. All were silent, except for Paganel, who talked to himself in Spanish, asking and answering questions.

The catapez was a naturally taciturn man, and his calling had not made him more talkative. He hardly spoke to his peons. They understood their duties perfectly. If one of the mules stopped, they urged it on with a guttural cry, and if that proved insufficient, a good-sized pebble, thrown with unerring aim, soon cured the animal’s obstinacy. If a strap came loose, or a rein fell, a peon came forward instantly and threw his poncho over the animal’s head to calm it until the tack could be repaired and the march resumed.

The custom of the muleteers was to start at eight o’clock, right after breakfast, and not to stop until they made camp for the night, about four o’clock in the afternoon. Glenarvan kept with the practice, and the first halt was just as they arrived at Arauco, at the very end of the bay, without having abandoned the frothy edge of the ocean. To reach the western end of the 37th parallel, they would have to continue as far as Carnero Bay, twenty miles further, but Glenarvan’s agents had already scoured that part of the coast without encountering any sign of the sinking. To repeat the exploration would have been pointless. It was, therefore, decided that Arauco should be their jumping off point, and that they should strike inland from from there.

The little troop entered the city to spend the night, and encamped in an inn, the comfort of which was still rudimentary.

Arauco is the capital of Araucanía, a country a hundred and fifty leagues long, thirty wide, and inhabited by the Mapuche, the descendants of the Chilean race sung of by the poet Ercilla.2 A proud and strong people, the only one in the two Americas that has never submitted to foreign domination.3 If Arauco once belonged to the Spaniards, the people, at least, had not submitted. They resisted the Spaniards as they now resisted the invading Chileans, and their independent flag — a white star on a field of azure — still floated at the top of the fortified hill which protected the city.

While supper was being prepared, Glenarvan, Paganel, and the catapez walked among the thatched houses. Except for a church and the remains of a Franciscan convent, Arauco offered little to the curious tourist. Glenarvan tried unsuccessfully to gather some information. Paganel was desperate to make himself understood by the inhabitants; but since they spoke Araucanían, a tongue that was in general use all the way to the Strait of Magellan, Paganel’s Spanish served him as well as Hebrew. He had to use his eyes, rather than his ears in his scholarly pursuits, and took great delight in observing the variety of Mapuche people around him. The men were tall, with flat faces, coppery complexions, shaved chins, skeptical eyes, and large heads lost in long black hair. They seemed doomed to the special idleness of warriors who do not know what to do in peacetime. Their grim and courageous wives were busy with the hard work of the household: grooming the horses, cleaning the weapons, ploughing, hunting for their husbands, and still finding time to weave richly embroidered ponchos that required two years to make, and could sell for over 100 dollars.4

In short, these Mapuches were an uninteresting people, with rather wild manners. They have almost all the human vices, against one virtue: the love of independence. “True Spartans,” said Paganel, when his walk was over, and he took his place at the evening meal.

The worthy scholar perhaps exaggerated the qualities of the Mapuches, and was even less understood when he added that his French heart was beating loudly during his visit to the city of Arauco. When the Major asked him the reason for this unexpected “beating,” he replied that his emotion was very natural, since a fellow Frenchman had once occupied the throne of Araucanía. The Major begged him to be good enough to make known the name of this sovereign. Jacques Paganel proudly named the brave Orélie-Antoine de Tounens, an excellent man, a former lawyer from Perigueux, a little too bearded, and who had undergone what dethroned kings like to call “the ingratitude of their subjects.”5 The Major smiled slightly at the idea of a former solicitor driven from the throne, Paganel replied very seriously that it was perhaps easier for a lawyer to make a good king, than for a king to make a good lawyer.

And on that note, everyone laughed and drank a few drops of chicha6 to the health of Orélie-Antoine Ier, the former King of Araucanía. A few minutes later the travellers, wrapped in their ponchos, were all soundly asleep.

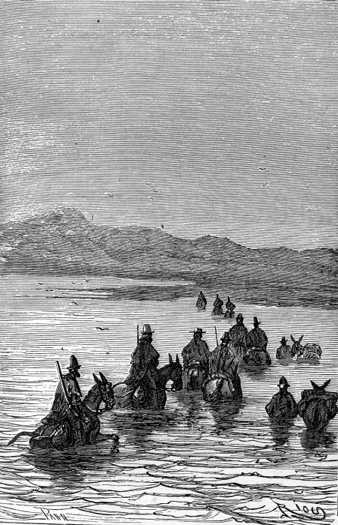

The ford of the Rio de Tubal

The next day, at eight o’clock, with the madrina at the head, and the peons at the tail, the little troop returned to following the 37th parallel to the east. They crossed the fertile territory of Araucanía, rich in vineyards and herds. But, little by little, it became more desolate. Sometimes, after miles without seeing anything they’d pass by a hut of a rastreadores, an Indian tracker, famous throughout America. Sometimes they’d see an abandoned post house, that served as a shelter for a wandering plains native. Their route was intersected by two rivers: the Rio de Raque and the Rio de Tubal. But the catapez led them to fords that allowed them to cross. The chain of the Andes unfolded on the horizon, its foothills swelling and peaks multiplying. These were still the low vertebrae of the enormous spine running down the back of the New World.

At four o’clock in the evening, after a journey of thirty-five miles, they stopped in the middle of the countryside under a bouquet of giant myrtle. The mules were unbridled, and went off to graze the thick grass of the meadow. The alforjas supplied the accustomed meat and rice. The pelions laid out on the ground served as blankets and pillows, and each of them found a restful repose on these improvised beds, while the peons and the catapez took turns keeping watch.

Since the weather remained so favourable, the whole party was in perfect health, and the journey had commenced under such happy auspices, the entire party wanted to push forward as quickly as possible. The next day they marched thirty-five miles or more, crossed the Bell Rapids without incident, and encamped at nightfall on the banks of Rio Biobio which separates Spanish Chile from independent Chile. The country was still rich and fertile, and abounded in amaryllis, tree violets, fluschies, daturas and cactuses with golden flowers. Some animals were seen among the brush, but there were not many natives. A few guassos, the degenerate offspring of Indians and Spaniards, passed like shadows on horses galloping across the plain. The horses’ flanks were bloodied by cruel thrusts from the spurs of their riders’ feet. It was impossible to make inquiries when there was no one to question, and Lord Glenarvan came to the conclusion that Captain Grant must have been dragged right over the Andes into the Pampas, and that it would be useless to search for him elsewhere. The only thing to be done was to press forward with all the speed in their power.

On the 17th they set out in the usual line of march, a line which was difficult for Robert to keep. His eagerness constantly compelled him to get ahead of the madrina, to the great despair of his mule. Nothing but a sharp recall from Glenarvan kept the boy in proper order.

The country became more rugged, and the rising ground promised future mountains. Rivers were more numerous, and came rushing noisily down the slopes. Paganel consulted his maps, and when he found any of these streams not marked, which happened often, all the fire of a geographer would burn in his veins.

“An unnamed river is like having no civil standing,” he would declare with charming anger. “It has no existence in the eye of geographical law!”

He did not hesitate to baptize these unnamed rivers, and mark them down on the map, qualifying them with the most high-sounding adjectives he could find in the Spanish language.

“What a language!” he said. “How full and sonorous it is! It is like the finest bronze that church bells are made of — composed of seventy-eight parts of copper and twenty-two of tin.”

“But do you make any progress in it?” asked Glenarvan.

“Most certainly, my dear Lord. Ah, if it wasn’t the accent, that wretched accent!”

And for want anything better to do, Paganel whiled away the time along the road by practising the difficulties in pronunciation, repeating all the jawbreaking words he could, though still making geographical observations. Any question about the country that Glenarvan might ask the catapez was sure to be answered by the learned Frenchman before he could reply, to the great astonishment of the guide, who gazed at him in bewilderment.

About ten o’clock that same day they came to a crossroad, and naturally enough Glenarvan inquired the name of it.

“It is the road from Yumbel to Los Ángeles,” said Paganel.

Glenarvan looked at the catapez.

“Quite right,” he said. Turning toward the geographer, he added “You have traveled in these parts before, sir?”

“Parbleu!” said Paganel, seriously.

“On a mule?”

“No, in an armchair.”

The catapez did not understand, but shrugged his shoulders and resumed his post at the head of the party.

At five in the evening they stopped in a shallow gorge, some miles above the little town of Loja, and encamped for the night at the foot of the Sierras, the first rungs of the great Cordillera.

1. The arrobe is a local measure equivalent to 11.5 kilograms

2. Alonso de Ercilla was a sixteenth century Spanish nobleman, soldier and poet, who wrote an epic poem, La Araucana, about the Araucanían insurrection — DAS

3. This was not to last much longer. The Chilean Occupation of Araucanía was completed by 1883 — DAS

4. 500 francs

5. Orélie-Antoine de Tounens’ “subjects”, the Mapuches, seemed to be quite happy with him. It was the government authorities of Chile who took exception, arrested him, declared him insane, and shipped him back to France — DAS

6. Fermented corn brandy