Antuco Pass

The passage through Chile had taken place without serious incident, but all the obstacles and dangers of a mountain journey were about to crowd on the travellers. The struggle with the natural barrier was truly beginning.

An important question had to be resolved before they began. Which pass would take them over the Andes, without taking them too far away from the 37th parallel? Lord Glenarvan asked the catapez.

“I do not know,” he said, “but there are only two practicable passes that I know of in this part of the Cordilleras.”

“One is undoubtedly the pass of Arica discovered by Valdivia Mendoze,” said Paganel.

“Exactly.”

“And the other is that of Villarica, located south of Nevado.”

“Just so.”

“Well, my good fellow, both these passes have only one fault; they take us too far out of our route, either north or south.”

“Have you another pass to propose?” asked the Major.

“Certainly,” said Paganel. “There is the Antuco Pass, on the slope of the volcano, in latitude, 37° 30′ , or, in other words, only half a degree out of our way. It is only a thousand fathoms high and has been scouted by Zamudio de Cruz.”

“That would do,” said Glenarvan. “Are you acquainted with this Antuco Pass, catapez?”

“Yes, your Lordship, I have crossed it, but I did not mention it, as it is just a cattle path used by the Indian shepherds of the eastern slopes.”

“Well, my friend,” said Glenarvan, “where the herds of mares, sheep, and oxen of the Pehuenches pass, we shall pass as well. And since this keeps us on the right line, head for the Antuco Pass.”

The signal for departure was given immediately, and they struck into the heart of the valley of Las Lejas, between great masses of crystalline limestone. At first they ascended a gentle slope. At about eleven o’clock it was necessary to skirt the banks of a small lake, a natural reservoir, and a scenic rendezvous of all the neighbouring rivers. The streams arrived there murmuring and mingled in a clear tranquil pool. Above the lake lay vast llanos, high plains covered with grasses, where Indian flocks grazed. They had to cross a marsh, running south and north, but the mules had an instinct that kept them from becoming mired in it. At one o’clock, Fort Ballenare appeared on a steep rock, which it crowned with its crumbling curtain wall. They continued on. The slopes were getting steeper, and strewn with loose stones and pebbles which the hoofs of the mules sometimes dislodged, triggering noisy cascades of stones. About three o’clock, they came across picturesque ruins of another fort, destroyed in the uprising of 1770.

“Apparently, the mountains are not a sufficient barrier to separate men, we must strengthen them!” said Paganel.

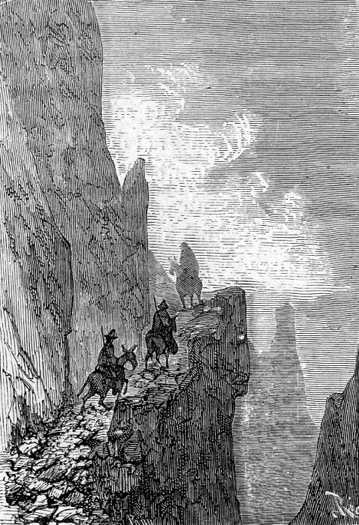

From this point the pass began to be difficult, and even dangerous. The slopes steepened, the ledges narrowed, and frightful precipices fell off to their sides. The mules went cautiously, keeping their heads near the ground, as if scenting the track. They went on in single file. Sometimes the madrina would disappear around a sudden bend of the road, and the little caravan guided itself by the distant tinkle of her bells. Often some capricious winding would bring the column in two parallel lines, and the catapez could speak to his peons across a crevasse not two fathoms wide, though two hundred deep, creating an uncrossable abyss between them.

Vegetation still struggled to take root against the invasions of stone. There was a feeling of the mineral and vegetable kingdoms struggling against one another. A few rust-coloured lava streaks, bristling with needle-shaped yellow crystals, showed they were approaching the volcano of Antuco. The rocks, piled on top of each other, and ready to fall, stood against all the laws of balance. Any sort of trembler would tumble these poorly seated formations down. The time of final settling had not yet come to this mountainous region.

Under these conditions, the path became difficult to recognize. The almost incessant agitation of the Andean spine often changes its shape, and the landmarks shifted. The catapez hesitated; he stopped; he looked around him; he examined the shape of the rocks; he sought traces of Indians on the friable stone. Orientation became more difficult.

Antuco Pass

Glenarvan followed his guide step by step. He saw that he was becoming more perplexed as the way became more difficult, but did not dare to interrogate him, perhaps thinking, rightly enough, that both mules and muleteers were very much governed by instinct, and it was best to trust them.

The catapez kept wandering about, almost haphazardly, for another hour, though always getting higher up the mountains. At last he was obliged to stop short. They were in a narrow valley, one of those gorges the Indians called quebradas, and on reaching the end, a wall of porphyry rose perpendicularly before them, and barred further passage. The catapez, having vainly sought to find an opening, dismounted, crossed his arms, and waited. Glenarvan went up to him.

“Have we gone astray?” he asked.

“No, My Lord,” said the catapez.

“But we are not in the pass of Antuco.”

“We are.”

“You are sure you are not mistaken?”

“I am not mistaken. See! There are the remains of a fire left by the Indians, and there are the marks of their mares and sheep.”

“They must have gone on, then.”

“Yes, but no more will go; the last earthquake has made the route impassable.”

“To mules,” said the Major, “but not to men.”

“That is your business,” said the catapez. “I have done all I can. My mules and myself are at your service to try the other passes of the Cordilleras.”

“And that would delay us?”

“Three days at least.”

Glenarvan considered the matter. The catapez knew his business and was clearly correct. His mules could go no farther. However, when the proposal was made to turn back, Glenarvan turned to his companions.

“Do you want to go on, anyway?”

“We will follow you,” said Tom Austin.

“And even precede you,” said Paganel. “What is it after all? We have only to cross a mountain range, whose opposite slopes offer an incomparably easier descent! That done, we shall find baqueanos, Argentinian shepherds, who will guide us through the Pampas, and swift horses accustomed to galloping over the plains. Forward then, I say, and without hesitation.”

“Forward!” cried Glenarvan’s companions.

“You will not go with us, then?” Glenarvan asked the catapez.

“I am a mule driver.”

“As you please,” said Glenarvan.

“We can do without him,” said Paganel. “On the other side of this wall we shall find the Antuco Pass again, and I’m quite sure I can lead you to the foot of the mountain as straight as the best guide in the Cordilleras.”

Glenarvan settled accounts with the catapez, and bade farewell to him and his peons and mules. Weapons, instruments, and a small stock of provisions were divided among the seven travellers, and it was unanimously agreed that the ascent should recommence at once, and, if necessary, should continue into the night. There was a very steep winding path on the left, which the mules never would have attempted. It was toilsome work, but after two hours’ exertion and detours, the little party found themselves once more in the trail through Antuco Pass.

They were in the Andes proper, now, and not far now from the upper ridge of the Cordilleras, but the clear path petered out again. The entire region had been overturned by recent earthquakes, and all they could do was keep on climbing higher and higher. Paganel was rather disconcerted at finding no clear way out to the other side of the chain, and expected great hardships before the topmost peaks of the Andes could be crossed, for their mean height is between 11,000 and 12,600 feet. Fortunately the weather was calm, the sky clear, and the season favourable, but in winter, from May to October, such an ascent would have been impossible. The intense cold quickly kills travellers, and those who manage to hold out against it fall victims to the violence of the temporales, a sort of hurricane peculiar to these regions, which yearly fills the abysses of the Cordilleras with dead bodies.

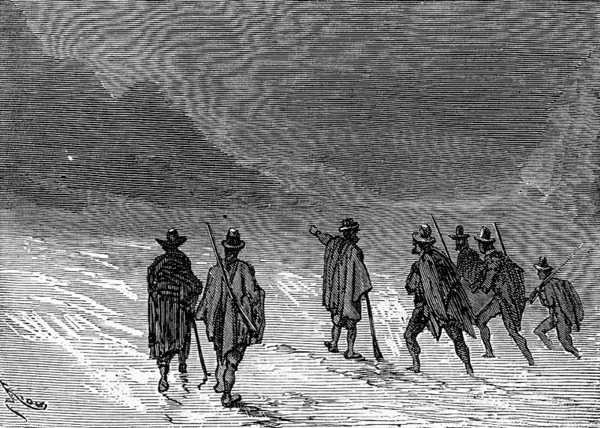

They went on, toiling steadily upward through the night, hoisting themselves up to almost inaccessible plateaus, and leaping over broad, deep crevasses. They had no ropes, but arms linked in arms supplied the lack, and shoulders served for ladders. These intrepid men looked like a troop of acrobats competing in mad Icarian games. The strength of Mulrady and the dexterity of Wilson were taxed heavily now. These two brave Scots were worth a troop by themselves. But for their devotion and courage the small band could not have gone on. Glenarvan never let Robert out of his sight, for his youth and energy made him imprudent. Paganel on the other hand, advanced with a French fury. In contrast, The Major only went as quickly as was necessary, neither more nor less, climbing without any apparent exertion, as if he didn’t know that he was climbing at all, or perhaps he fancied himself descending.

At five o’clock in the morning, the travellers had reached a height of 7,500 feet

At five o’clock in the morning, the travellers had reached a height of 7,500 feet, determined by a barometric observation. They were on the secondary plateaus, approaching the tree line. The animals that lived there that would have made a hunter happy, or rich. These agile creatures knew it, too, for they fled from the approach of men. The llama: a valuable mountain camelid, that replaces sheep, oxen and horses, and lives where even mules would not go. The chinchilla: a small, gentle and fearful rodent, rich in fur, looking like a cross between a hare and a jerboa, and with hind legs like those of a kangaroo. Nothing was as charming as watching this light animal running across the tops of the trees like a squirrel. “It’s not a bird yet,” said Paganel, “but it’s no longer a quadruped.”

These animals were not the last inhabitants of the mountain, however. At 9,000 feet, on the edge of the perpetual snows, were ruminants of incomparable beauty, the alpaca, with long, silky fur. And then a sort of horned, elegant and proud goat, with fine wool, that naturalists have named the vicuña. But it was nigh impossible to approach it, and it was difficult to even glimpse it. They fled, swiftly and silently gliding on dazzling mats of whiteness.

The whole aspect of the region had changed completely. Huge blocks of glittering ice rose in ridges on all sides, glittering blue in the early light of day. The ascent became very perilous. No one moved without probing carefully for crevasses. Wilson took the lead, and tried the ground with his feet. His companions followed exactly in his footprints. They lowered their voices to a whisper, as the least sound could disturb the masses of snow suspended seven or eight hundred feet above their heads, and bring it down upon them in an avalanche.

They passed through a region of shrubs and bushes which, 250 fathoms higher gave way to grasses and cacti. At 11,000 feet even these hardy plants had abandoned the arid soil, and all trace of vegetation disappeared. They had only stopped once, at eight o’clock, to rest and snatch a hurried meal to restore their strength. With superhuman courage, they resumed their ascent amid ever increasing dangers. They were forced to mount sharp peaks and leap over chasms so deep that they did not dare to look down them. They followed a route marked out by wooden crosses, each bearing witness to some past tragedy.

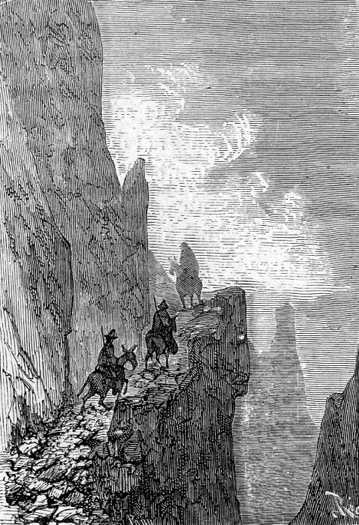

An immense plateau … stretched out between gaunt peaks

About two o’clock they came to an immense plateau, without a sign of vegetation. A kind of desert stretched out between gaunt peaks. The air was dry and the sky deep, clear blue. At this elevation rain is unknown, and vapours only condense into snow or hail. Here and there peaks of porphyry or basalt pierced through the white shroud like the bones of a skeleton. Fragments of quartz or gneiss, loosened by the action of the air, fell at times with a faint, dull sound which was almost imperceptible in the sparse atmosphere.

Despite their courage, the little band was becoming exhausted. Glenarvan, seeing how tired his men had become, regretted having pressed so high into the mountains. Young Robert held out manfully, but he could not go much farther. At three o’clock Glenarvan stopped.

“We must rest,” he said, for he knew that if he did not propose it himself, no one else would.

“Rest?” asked Paganel. “But we have no place to shelter.”

“It is absolutely necessary, however, if only for Robert.”

“No, no, My Lord,” said the courageous child. “I can still walk. Don’t stop.”

“You shall be carried, my boy; but we must get to the other side of the Cordilleras, whatever the cost,” said Paganel. “There we may perhaps find some hut to cover us. All I ask is another two hours of walking.”

“Are you all of the same opinion?” asked Glenarvan.

“Yes,” was the unanimous reply.

“I’ll carry the boy,” said Mulrady.

They resumed the eastward march. It was another two hours of a frightening ascent to reach the highest peaks of the mountains. The rarefaction of the atmosphere produced that painful condition known as puna. Blood oozed from the gums and lips, from the lack of air pressure, and perhaps also under the influence of the snow, which at a great height vitiates the atmosphere. The lack of air made their inhalations more rapid, as they desperately tried to fill their lungs, which only tired them more quickly. The reflection of the sun off the snow blinded them. Whatever the will of these courageous men, the moment came when the most valiant fainted, and vertigo, that terrible mountain sickness, destroyed not only their physical strength, but also their determination. No one could fight with impunity against such fatigues. Soon the falls became frequent, and those who fell advanced only by crawling.

But just as exhaustion was about to make an end to any further ascent, and Glenarvan’s heart began to sink as he thought of the snow spreading out as far as the eye could reach, and of the intense cold, and saw the shadow of night fast overspreading the desolate peaks, and knew they had no roof to shelter them, suddenly the Major stopped, and spoke in a calm voice.

“A hut!”