Robert grasped the Lord’s hand and lifted it to his lips.

Laguna Epecuén lies at the end of the string of lagoons connecting the Sierra de la Ventana with Guamini. In the past, numerous expeditions had come there from Buenos Aires to collect the salt deposited on its banks, as the waters contain great quantities of sodium chloride, deposited when the water was evaporated by the fiery heat of the sun.

When Thalcave spoke of the laguna as supplying drinkable water he was thinking of the rios of fresh water which run into it at many places. Those streams, however, were all dried up, like the laguna. The burning sun had drunk everything, to the consternation of the travellers.

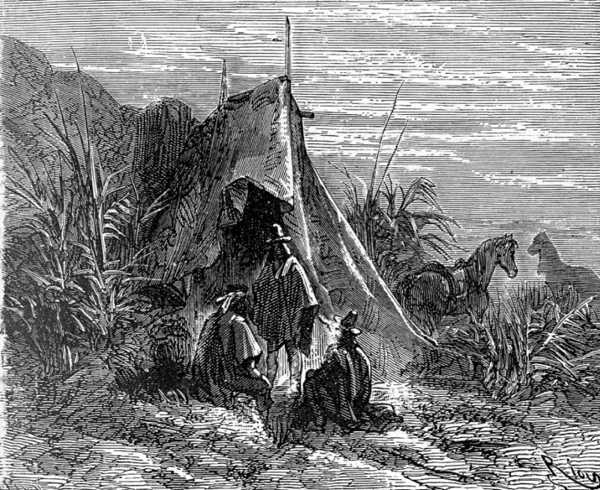

Some action had to be taken immediately, for what little water still remained in their bottles was tainted, and could not be used to quench their thirst. Hunger and fatigue were forgotten in the face of this driving need. A sort of leather tent, called a roukah, which had been abandoned by the natives afforded the party a temporary resting-place, and the weary horses stretched themselves along the muddy banks, and tried to browse on the marine plants and dry reeds they found there — nauseous to the taste as they must have been.

As soon as the whole party were ensconced in the roukah, Paganel asked Thalcave what he thought was best to be done. A rapid conversation followed, a few words of which were intelligible to Glenarvan. Thalcave spoke calmly, but the lively Frenchman gesticulated enough for both. After a little, Thalcave sat silently and folded his arms.

“What does he say?” asked Glenarvan. “I fancied he was advising us to separate.”

“Yes, into two parties,” said Paganel. “Those of us whose horses are so done in with fatigue and thirst that they can scarcely put one foot in front of the other are to continue on the road of the 37th parallel as best they can, while the others, whose steeds are fresher, are to push on in advance toward the river Guamini, which flows into Lake San Lucas about thirty-one miles off.1 If there is enough water in the river, they are to wait there until their companions reach them; but should it be dried up, they will hasten back and spare them a useless journey.”

“And what will we do then?” asked Austin.

“Then we shall have to make up our minds to go 75 miles south, as far as the ramparts of the Sierra Ventana, where rivers abound.”

“It is wise counsel,” said Glenarvan, “and we will act upon it immediately. My horse is in tolerable good trim, and I volunteer to accompany Thalcave.”

“Oh, My Lord, take me!” said Robert, as if it were a question of some pleasure party.

“But would you be up for it, my boy?”

“Oh, I have a fine horse, which just wants to have a gallop. Please, My Lord, take me.”

“Come, then, my boy,” said Glenarvan, delighted not to leave Robert behind. “If we three don’t manage to find fresh water somewhere,” he added, “we must be very stupid.”

“And what about me?” asked Paganel.

“Oh, my dear Paganel, you must stay with the reserve corps,” said the Major. “You are too well acquainted with the 37th parallel and the river Guamini and the whole Pampas for us to let you go. Neither Mulrady, nor Wilson, nor myself would be able to rejoin Thalcave at the given rendezvous, but we will put ourselves under the banner of the brave Jacques Paganel with perfect confidence.”

“I resign myself,” said the geographer, much flattered at being given such responsibility.

“But no distractions,” added the Major. “Don’t you take us to the wrong place — to the borders of the Pacific, for instance.”

“It would serve you right, insufferable Major,” laughed Paganel. “But how will you manage to understand what Thalcave says, Glenarvan?”

“I don’t suppose that we’ll have much to talk about,” said Glenarvan. “Besides, I know a few Spanish words. In a pinch, I think we can understand each other.”

“Then go, my good friend,” said Paganel.

“We’ll have supper first,” said Glenarvan, “and then sleep, if we can, until it is time to go.”

The supper was not very reviving without drink of any kind, and they tried to make up for the lack of it by a good sleep. But Paganel dreamed of water all night, of torrents and cascades, and rivers and ponds, and streams and brooks, and full carafes. It was a complete nightmare.

At six o’clock the next morning, Thalcave, Glenarvan and Robert saddled their mounts. Their last ration of water was given to the horses, and drunk with more avidity than satisfaction, for it was filthy, disgusting stuff. The three horsemen climbed into their saddles.

“Goodbye,” said the Major, Austin, Wilson and Mulrady.

“And whatever you do, try not to come back!” called Paganel after them.

Soon, Thalcave, Glenarvan and Robert lost sight of the detachment entrusted to the wisdom of the geographer, not without a certain heart-ache.

The desierto de las Salinas, which they had to traverse, is a clay plain covered with stunted shrubs no higher than ten feet, and small mimosas which the Indians call curra-mammel; and jumes, a bushy shrub, rich in soda. Here and there large pans were covered with salt, which sparkled in the sunlight with astonishing brilliancy. These barreros2 might easily have been taken for sheets of ice, had not the intense heat forbidden the illusion. The contrast these dazzling white sheets presented to the dry, burned-up ground gave the desert a most peculiar character.

Eighty miles south,3 the Sierra de la Ventana, to which the possible drying up of the Guamini might force travellers to descend, presented a different aspect. This country, explored in 1835 by Captain FitzRoy, who then commanded the Beagle’s expedition, is of superb fertility. The best pastures of Indian territory grow there with unparalleled vigour. The north-west slope of the mountain range is covered with lush grass, and descends into rich mixed forests. There grow the algarrobo, a sort of carob tree, whose dried fruit, reduced to flour, is used to make a bread that is highly esteemed by the Indians; the white quebracho with its long, flexible branches that weep like the European willow; the red quebracho with an indestructible wood; the naudubay, which can be ignited with extreme ease, and often causes terrible fires; the viraro, whose violet flowers are pyramid shaped, and finally the timbo, which spreads its immense parasol eighty feet in the air, and under which whole herds can shelter against the sun’s rays. The Argentinians have often tried to colonize this rich country, without succeeding in overcoming the hostility of the Indians.

Of course, it was to be believed that abundant rivers descended from the rumps of the mountains, to supply the water necessary for so much fertility, and, indeed, the greatest droughts never evaporated these rivers. Unfortunately, to reach them would require a march of 130 kilometres south; and this was why Thalcave thought it best to go first to Guamini, as it was not only much nearer, but also on the direct line of their quest.

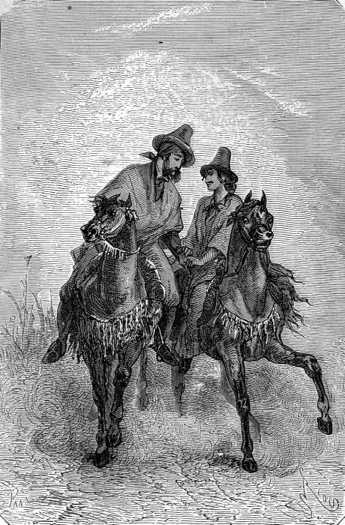

The three horses galloped with enthusiasm, as if instinctively knowing where their masters led them. Thaouka especially displayed a courage that neither fatigue nor hunger could damp. She bounded like a bird over the dried-up canadas and the curra-mammel bushes, her loud, joyous neighing seeming to bode success to the search. The horses of Glenarvan and Robert, though not so light-footed, felt the spur of her example, and followed her bravely. Thalcave, motionless in the saddle, inspired his companions as much as Thaouka did her four-footed brethren. Thalcave often turned his head to consider Robert Grant.

Seeing the young boy, firm and well seated, with supple back, shoulders relaxed, legs falling naturally, knees fixed to the saddle, he showed his satisfaction with an encouraging cry. In truth, Robert Grant had become an excellent horseman and deserved the compliments of the Indian.

“Bravo! Robert,” said Glenarvan. “Thalcave is evidently congratulating you, my boy, and paying you compliments.”

“What for, My Lord?”

“For your good horsemanship.”

“I’m standing firmly, that’s all,” said Robert, blushing with pleasure at such an encomium.

“That is the main thing, Robert,” said Glenarvan, “But you are too modest. I tell you that some day you will turn out an accomplished horseman.”

“What would papa say to that?” said Robert, laughing. “He wants me to be a sailor.”

“The one doesn’t prevent the other. Even if all cavaliers won’t make good sailors, there is no reason why all sailors should not make good cavaliers. To keep one’s footing on the yards teaches a man balance, and to hold on firm. Both are skills needed for horsemanship. After that, making a horse go through all sorts of movements, that’s easily acquired. Indeed, it comes naturally.”

“Poor father,” said Robert, “how he will thank you for saving his life.”

“You love him very much, Robert?”

“Yes, My Lord, dearly. He was so good to me and my sister. We were his only thought. And whenever he came home from his voyages, we were sure of some souvenir from all the countries he had visited; and, better still, of loving words and hugs. Ah! if you knew him you would love him, too. Mary is most like him. He has a soft voice, like hers. That’s strange for a sailor, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Robert, very strange.”

“I see him still,” the boy went on, as if speaking to himself. “Good, brave papa. He put me to sleep on his knee, crooning an old Scottish ballad about the lochs of our country. The song sometimes comes back to me, but very confused like. To Mary, too. Ah, My Lord, how we loved him. Well, I do think one needs to be little to love one’s father like that.”

“Yes, and to be grown up, my child, to venerate him,” replied Glenarvan, deeply touched by the boy’s genuine affection.

During this conversation the horses had been slackening speed, and were only walking now.

“We’ll find him, won’t we?” said Robert again, after a few minutes’ silence.

“Yes, we’ll find him,” said Glenarvan. “Thalcave has set us on the track, and I have great confidence in him.”

“Thalcave is a brave Indian, isn’t he?” said the boy.

“Certainly.”

“Do you know something, My Lord?”

“Tell me, and I will tell you.”

“There are only good people with you. Lady Helena, whom I love so, and the Major, with his calm manner, and Captain Mangles, and Monsieur Paganel, and all the sailors on the Duncan. How courageous and devoted they are.”

“Yes, my boy, I know that,” replied Glenarvan.

“And do you know that you are the best of all?”

“No, most certainly I don’t know that.”

Robert grasped the Lord’s hand and lifted it to his lips.

“Well, it is time you did, My Lord,” said the boy, who grasped the Lord’s hand and lifted it to his lips.

Glenarvan shook his head, but said no more, as a gesture from Thalcave made them spur their horses on and hurry forward. It was necessary not to waste time for the sake of those who remained behind.

They resumed their rapid pace, but it was soon evident that, with the exception of Thaouka, the wearied animals could not go quicker than a walking pace. At noon they were obliged to let them rest for an hour. They could not go on at all, and refused to eat the tufts of alfafares, a kind of lean alfalfa roasted by the sun’s rays.

Glenarvan became worried. The symptoms of infertility did not diminish, and the lack of water could have disastrous consequences. Thalcave said nothing, thinking probably, that it would be time enough to despair if the Guamini should be dried up — if, indeed, his heart could ever despair.

Spur and whip both had to be employed to induce the poor animals to resume the route, and then they only crept along, for their strength was gone.

Thaouka, indeed, could have galloped swiftly enough, and reached the rio in a few hours. She must have thought of it, but Thalcave would not leave his companions behind, alone in the midst of a desert, so he forced Thaouka to slow to the pace of the other horses.

It was hard work, however, to get the animal to consent to walk quietly. She kicked, and reared, and neighed violently, and was subdued at last more by her master’s voice than hand. Thalcave talked to the horse, and Thaouka, if she did not answer, understood him at least. It must be believed that the Patagonian gave her excellent reasons, for after having “discussed,” the matter for some time, Thaouka yielded to his arguments and obeyed — though she still champed the bit.

But if Thaouka understood Thalcave, Thalcave had not less understood Thaouka. The intelligent animal, served by superior senses, felt humidity in the air and drank it in with frenzy, moving and making a noise with her tongue, as if taking deep draughts of some cool refreshing liquid. The Patagonian could not mistake her now — water was not far off.

The two other horses seemed to catch their comrade’s meaning, and, inspired by her example, made a last effort, and galloped forward after the Indian.

About three o’clock a bright line appeared in a fold of the ground, and seemed to tremble in the sunlight.

“Water!” exclaimed Glenarvan.

“Yes, yes! It’s water!” shouted Robert.

The horses plunged up to their chests in the water

They no longer had to urge their horses on. With revived strength, the poor creatures carried them irresistibly forward. In a few minutes they had reached the Rio de Guamini, and plunged up to their chests in the beneficent waters.

Their masters plunged in too, in spite of themselves, and took an involuntary bath, of which they did not think to complain.

“Oh, that’s good!” said Robert, taking a deep draught in the open air.

“Drink moderately, my boy,” said Glenarvan; but he did not practice what he preached.

Thalcave drank quietly, without hurrying himself, taking small gulps, but “as long as a lasso,” as the Patagonians say. He seemed as if he were never going to finish, and there was some danger of his swallowing up the whole river.

“Well, our friends won’t be disappointed when they get here,” said Glenarvan, after he had drunk his fill. “They will be sure of finding clear, cool water — that is, if Thalcave leaves any for them.”

“But couldn’t we go to meet them?” asked Robert. “It would spare them several hours’ suffering and anxiety.”

“You’re right my boy; but how could we carry them this water? The leather bottles were left with Wilson. No; it is better for us to wait for them as we agreed. They can’t be here until about the middle of the night, so the best thing we can do is to get a good bed and a good supper ready for them.”

Thalcave had not waited for Glenarvan’s proposition to to look for a campsite. He had been fortunate enough to discover a ramada on the banks of the rio, a sort of enclosure which had served as a fold for flocks that was shut in on three sides. It was an excellent place to spend the night, provided that you had no fear of sleeping out under the stars, and none of Thalcave’s companions had any objections to that. So they took possession at once, and stretched themselves out on the ground in the bright sunshine, to dry their dripping clothes.

A ramada stood on the banks of the rio

“Well, now we’ve secured a lodging, we must think of supper,” said Glenarvan. “Our friends must not have reason to complain of the couriers they sent ahead, and I don’t propose to disappoint them. It strikes me that an hour’s shooting won’t be wasted time. Are you ready, Robert?”

“Yes, My Lord,” replied the boy, standing up, rifle in hand.

It was clear why Glenarvan had this idea. The banks of the Guamini seemed to be the rendezvous of all the game of the surrounding plains. The tinamous, a type of Pampas partridge; black jellies; a species of plover named teru-teru; yellow rays; and water fowl with beautiful green plumage rose in coveys.

At first, they couldn’t see any sort of four footed game, but Thalcave, indicated the tall grasses and thick brush lining the river, and made it clear that they were hidden there. The hunters were only a few paces away from the most game-rich country in the world.

Disdaining the feathered tribes when more substantial game was at hand, the hunters’ first shots were fired into the underwood. Instantly there rose by the hundred roebucks and guanacos, like those that had swept over them that terrible night on the Cordilleras, but the timid creatures were so frightened that they were all out of range in an instant. The hunters were obliged to content themselves with slower game, which still left nothing to be desired from an alimentary point of view. A dozen tinamous and rays were quickly brought down, and Glenarvan skilfully killed a tay-tetre, or peccary: an American wild pig, the flesh of which is excellent eating.

In less than half an hour the hunters had all the game they required. Robert had killed a curious animal belonging to the order Edentata, an armadillo, covered with a hard bony shell, in movable pieces, and measuring a foot and a half long. It was very fat and Thalcave said it would make an excellent dish. Robert was very proud of his success. As for Thalcave, he gave his companions the show of hunting a rhea, a South American relative of the ostrich, remarkable for its extreme swiftness.

There could be no slow stalk of such a quick animal, and the Indian did not attempt it. He urged Thaouka to a gallop, to reach the rhea as quickly as possible. In a chase, if the first attack failed, the bird would soon tire out both horse and rider by involving them in a corkscrew pursuit. As soon as Thalcave closed the distance, he flung his bolas with such a powerful hand, and so skilfully, that he caught the bird around the legs and immobilized it immediately. In a few seconds it lay flat on the ground.

The Indian had not made his capture for the mere pleasure and glory of such a novel chase. The flesh of the rhea is highly esteemed, and Thalcave felt bound to contribute his share to the common repast.

They returned to the ramada, bringing back the string of partridges, the rhea, the peccary, and the armadillo. The rhea and the peccary were skinned at once, and cut into thin slices to prepare them for cooking. As for the armadillo, it carried its rotisserie with it, and it was placed in its own shell over the glowing embers.

The three hunters contented themselves with the bartavelles for their supper. The piece de resistance was reserved for their friends. They washed down their meal with clear, fresh water, which was pronounced superior to all the ports of the world, even to the famous usquebaugh4, so honoured in the Highlands of Scotland.

The horses had not been overlooked. A large quantity of dry fodder was discovered lying heaped up in the ramada, and this supplied them amply with both food and bedding.

When all was ready the three companions wrapped themselves in their ponchos, and stretched themselves on a quilt of alfafares, the usual bed of hunters on the Pampas.

1. Fifty kilometres.

2. Land impregnated with salt.

3. Thirty-two leagues. (130 kilometres — DAS)

The numbers in the Hetzel edition don’t add up in this section, converting eighty miles to “more than a hundred leagues.” I’ve corrected the conversion — DAS

4. Fermented barley brandy. (Whisky — DAS)