Thalcave struck them down with the butt of his rifle

Night came, a new moon night during which the orb of night was invisible to all the inhabitants of the earth. The dim light of the stars was all that illumined the plain. On the horizon, the zodiacal stars were extinguished in a dark haze. The waters of the Guamini ran silently, like a sheet of oil over a surface of marble. Birds, quadrupeds, and reptiles were resting motionless after the fatigues of the day, and the silence of the desert brooded over the far-spreading Pampas.

Glenarvan, Robert, and Thalcave had followed the common example, and lay in profound slumber on their soft couch of alfafares. The worn-out horses lay on the ground, except Thaouka, who slept standing, proud in repose as in action, and ready to launch at the slightest sign from her master. Absolute silence reigned within the enclosure, over which the dying embers of the fire shed a fitful light.

The Indian’s sleep did not last long; for at about ten o’clock he woke, sat up, and turned his ear toward the plain, listening intently with half-closed eyes, trying to catch some nearly imperceptible sound. An uneasy look began to appear on his usually impassive face. Had he caught scent of some party of Indian marauders, or of jaguars, water tigers, or other dreadful beasts that haunt the neighbourhood of rivers? This last hypotheses seemed most likely, for he threw a rapid glance on the combustible materials heaped up in the enclosure, and his anxiety deepened. All this dry litter of alfafares would soon burn out and could only ward off the attacks of wild beasts for a short time.

There was nothing to be done in the circumstances but wait; and wait he did, in a half-recumbent posture, his head leaning on his hands, and his elbows on his knees, like a man roused suddenly from his night’s sleep.

An hour passed, and anyone except Thalcave would have lain down again on his couch, reassured by the silence around him. But where a stranger would have suspected nothing, the sharpened senses of the Indian detected the approach of danger.

While he listened and watched, Thaouka gave a low neigh, and stretched her nostrils toward the entrance of the ramada. Thalcave straightened up.

“Thaouka scents an enemy.” He stood and went to the opening, to make a careful survey of the plains.

Silence still reigned, but not tranquillity. Thalcave glimpsed shadows moving noiselessly over the tufts of curra-mammel. Here and there luminous spots appeared, dying out and rekindling constantly, in all directions, like fantastic lights dancing over the surface of an immense lagoon. An inexperienced eye might have mistaken them for fireflies,1 which shine at night in many parts of the Pampas, but Thalcave was not deceived. He knew the enemies he had to deal with. He cocked his rifle and took up his post in front of the fence.

He did not wait long, for a strange cry, a confusion of barking and howling, broke over the Pampas, followed next instant by the report of the rifle, which made the uproar a hundred times worse.

Glenarvan and Robert, suddenly awake, jumped to their feet.

“What is it?” asked Robert.

“Indians?” asked Glenarvan.

“No,” said Thalcave. “Aguarás.”

“Aguarás?” said Robert, looking inquiringly at Glenarvan.

“Yes,” replied Glenarvan. “The red wolves of the Pampas.”

They seized their weapons at once, and stationed themselves beside the Patagonian, who pointed toward the plain whence arose a concert of howling.

Robert drew back involuntarily.

“You are not afraid of wolves, my boy?” said Glenarvan.

“No, My Lord,” said the lad in a firm tone, “and moreover, beside you I am afraid of nothing.”

“So much the better. These aguarás are not very formidable; and if it were not for their number I would not even care.”

“What does it matter?” said Robert. “We are all well armed; let them come.”

“We’ll certainly give them a warm reception.”

Glenarvan said this to reassure the boy, but this legion of carnivorous animals in the night filled him with a secret terror. There might be hundreds of them, and what could three men do, as well armed as they were, against such a multitude?

As soon as Thalcave said the word aguará, Glenarvan knew that he meant the red wolf, for this is the name given to it by the Pampas Indians. This voracious animal, called by naturalists the Canis jubatus,2 is shaped like a large dog, with the head of a fox. Its coat is a cinnamon red, and a black mane runs down its back. It is a strong, nimble animal, generally inhabiting marshy places, pursuing aquatic animals by swimming, prowling about by night and sleeping during the day. Its attacks are particularly dreaded at the estancias, or sheep stations, where it often wreaks considerable havoc. A lone aguará is not much to be feared; but a large pack was a different matter. It was better to have to deal with a jaguar or cougar that you could face straight on.

Both from the noise of the howling and the multitude of shadows leaping about, Glenarvan had a pretty good idea of the number of the wolves, and he knew they had scented a good meal of human flesh or horse flesh, and none of them would go back to their dens without a share. It was certainly a very alarming situation to be in.

The circle of wolves was gradually drawing closer. The awakened horses displayed signs of growing terror, with the exception of Thaouka, who stamped her foot, and tried to break loose and get out. Her master could only calm her by keeping up a low, continuous whistle.

Glenarvan and Robert had placed themselves so as to defend the opening of the ramada. They were just about to fire into the nearest ranks of the wolves when Thalcave lowered their weapons.

“What does Thalcave mean?” asked Robert.

“He forbids our firing.”

“Why?”

“Perhaps he thinks it is not the right time.”

This was not the Indian’s motive. He had more urgent reason, and Glenarvan understood it when Thalcave lifted his powder magazine and showed that it was almost empty.

“What’s wrong?” asked Robert.

“We must conserve our ammunition. Today’s shooting has cost us dear, and we are short of powder and shot. We do not have twenty shots left.”

The boy made no reply. “Are you afraid, Robert?”

“No, My Lord.”

“Good boy.”

A fresh report resounded that instant. Thalcave had made short work of one assailant more audacious than the rest, and the infuriated pack had retreated to a hundred paces from the enclosure.

On a sign from the Indian Glenarvan took his place, while Thalcave went back into the enclosure and gathered up all the dried grass and alfafares, and other combustibles he could rake together, and piled them by the entrance. Into this he flung one of the still-glowing embers from their fire, and soon a bright curtain of flames shot up into the dark night. Through its rents, it was now possible for Glenarvan to estimate the size of the pack they faced. It was larger than his worst fears, and the barrier of fire cutting them off from their prey only seemed to enrage them more. Several of them pushed forward to the fire itself, and didn’t retreat until it had burned their legs.

From time to time another shot had to be fired, notwithstanding the fire, to keep off the howling pack, and in the course of an hour fifteen dead animals lay stretched on the prairie.

The situation of the besieged was, relatively speaking, less dangerous now. As long as the powder lasted and the barrier of fire stood at the entrance to ramada, there was no fear of being overrun. But what was to be done afterward, when both means of defence failed at once?

Glenarvan’s heart swelled as he looked at Robert. He forgot himself in thinking of this poor child, as he saw him showing a courage so far above his years. Robert was pale, but he kept his gun steady, and stood firmly, ready to meet the attacks of the infuriated wolves.

However, after Glenarvan had calmly considered their situation, he resolved to put an end to it.

“In an hour,” he said, “we shall have no more shot, powder nor fire. It will never do to wait until then before we settle on what to do.”

Accordingly, he went up to Thalcave, and tried to talk to him by the help of the few Spanish words his memory could muster, though their conversation was often interrupted by one or the other having to fire a shot.

It was no easy task for the two men to understand each other, but, most fortunately, Glenarvan knew a great deal of the peculiarities of the red wolf; otherwise he could never have interpreted the Indian’s words and gestures.

A quarter of an hour still passed before he could pass on Thalcave’s answer about their desperate situation to Robert.

“What does he say?”

“He says that we must hold out until daybreak, whatever the cost. The aguará only goes out at night. In the morning they will return to their lairs. It is a cowardly beast, that loves the darkness and dreads the light — an owl on four feet.”

“Very well, let us defend ourselves, then, until morning.”

“Yes, my boy, and with a knife, when we can no longer do it with guns.”

Already Thalcave had set an example, for whenever a wolf came too near the burning pile, the long arm of the Patagonian dashed through the flames and came out again reddened with blood.

But very soon this means of defence would be at an end. Toward two o’clock in the morning, Thalcave flung their last armful of fuel into the fire, and only five shots remained to their guns.

Glenarvan threw a sorrowful glance round him. He thought of the lad standing there, and of his companions and those left behind, whom he loved so dearly. Robert was silent. Perhaps the danger seemed less imminent to his imagination. But Glenarvan thought for him, and pictured to himself the horrible prospect, now inevitable, of being eaten alive! Quite overcome by his emotion, he took the child in his arms, and hugged him convulsively to his breast, pressed his lips on his forehead, while tears he could not restrain streamed down his cheeks.

Robert looked up into his face with a smile, and said, “I am not frightened.”

“No, my child, no! and you are right. In two hours daybreak will come, and we shall be saved.”

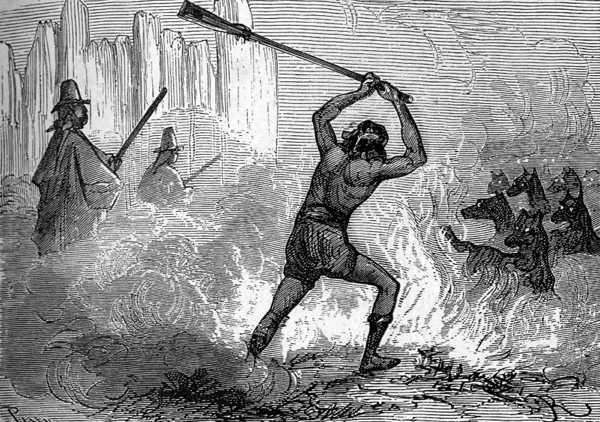

Thalcave struck them down with the butt of his rifle

At that moment, two wolves attempted to leap their dying fire. Thalcave struck them down with the butt of his rifle. “Bravo, Thalcave! my brave Patagonian! Bravo!”

But the fire was fast dying out, and the denouement of the bloody drama was approaching. The flames got lower and lower. Once more the shadows of night fell on the prairie, and the glaring eyes of the wolves glowed like phosphorescent balls in the darkness. In a few more minutes the whole pack would be in the enclosure.

Thalcave fired his rifle for the last time, killing one more enormous monster, and then folded his arms. His head bowed over his chest, and he meditated silently. Was he planning some daring, impossible, foolish attempt to repulse the infuriated horde? Glenarvan did not dare ask.

At this moment a change occurred in the attack of the wolves. The deafening howls suddenly ceased: they seemed to be going away. Gloomy silence spread over the prairie.

“They’re going!” said Robert.

But Thalcave, guessing his meaning, shook his head. He knew they would never relinquish their sure prey until daybreak made them go back to their dark dens.

Still, their tactics had obviously changed. The aguarás no longer attempted to force the entrance, but their new maneuvers only heightened the danger. They had given up on the frontal assault on the ramada, and were now trying to get in on the opposite side.

They heard their claws attacking the mouldering wood, and already formidable paws and hungry, savage jaws had found their way between the posts. The terrified horses broke loose from their halters and ran about the enclosure, mad with fear. Glenarvan put his arms around the young lad, and resolved to defend him as long as his life held out. Possibly he might have made a useless attempt at flight when his eye fell on Thalcave.

The Indian had been stalking about the ramada like a stag, when he suddenly stopped short, and going up to his horse, who was trembling with impatience, began to saddle him with the most scrupulous care, without forgetting a single strap or buckle. He seemed no longer to disturb himself in the least about the wolves outside, though their yells had redoubled in intensity. A dark suspicion crossed Glenarvan’s mind as he watched him.

“He is going to desert us,” he exclaimed at last, as he saw him seize the reins, as if preparing to mount.

“Him? Never!” said Robert.

And indeed, the Indian was not going to abandon his friends. He was going to attempt to save them by sacrificing himself.

Thaouka was ready, and stood champing her bit. She reared up, and her splendid eyes flashed fire; she understood her master.

But just as the Patagonian caught hold of the horse’s mane, Glenarvan seized his arm with a convulsive grip.

“You are going away?” he asked, pointing to the open prairie.

“Yes,” replied the Indian, understanding his gesture. Then he said a few words in Spanish, which meant: “Thaouka; good horse; quick; will draw all the wolves away after her.”

“Oh, Thalcave,” exclaimed Glenarvan.

“Quick, quick!” replied the Indian, while Glenarvan said, in a broken, agitated voice to Robert:

“Robert, my child, do you hear him? He wants to sacrifice himself for us. He wants to rush away over the Pampas, and divert the wolves from us by drawing them to himself.”

“Friend Thalcave!” Robert, threw himself at the feet of the Patagonian. “Friend Thalcave, don’t leave us!”

“No,” said Glenarvan, “he shall not leave us.”

And turning toward the Indian, he said, pointing to the frightened horses, “Let us go together.”

“No,” replied Thalcave, catching his meaning. “Bad horses. Frightened. Thaouka, good horse.”

“Be it so then!” returned Glenarvan. “Thalcave will not leave you, Robert. He teaches me what I must do. It is for me to go, and for him to stay by you.”

Then seizing Thaouka’s bridle, he said, “I am going, Thalcave, not you.”

“No,” replied the Patagonian quietly.

“I say to you,” exclaimed Glenarvan, snatching the bridle out of his hands. “It will be me! Save this boy, Thalcave! I entrust him to you.”

Glenarvan was so excited that he mixed up English words with his Spanish. But what mattered the language at such a terrible moment? A gesture was enough. The two men understood each other.

However, Thalcave would not give in, and the discussion continued, though every second’s delay increased the danger. Already the piles of the ramada were giving way to the teeth and claws of the wolves.

Neither Glenarvan nor Thalcave appeared inclined to yield. The Indian had dragged his companion toward the entrance of the ramada, and showed him the prairie, making him understand that now was the time when it was clear from the wolves; but that not a moment was to be lost, for should this maneuver not succeed, it would only render the situation of those left behind more desperate. and that he knew his horse well enough to be able to trust her wonderful lightness and swiftness to save them all. But Glenarvan was blind and obstinate, and determined to sacrifice himself at all hazards, when suddenly he felt himself violently pushed back. Thaouka pranced up, and reared herself bolt upright on her hind legs, and made a bound over the barrier of fire, while a clear, young voice called out:

“God save you, My Lord!”

And Glenarvan and Thalcave barely had time to catch sight of Robert, who, clinging to the mane of Thaouka, disappeared into the darkness.

“Robert! oh you unfortunate boy,” cried Glenarvan.

The red wolves launched in pursuit of the horse.

But even Thalcave did not catch the words, for his voice was drowned in the frightful uproar made by the wolves, who had dashed off at a tremendous speed in pursuit of the horse.

Thalcave and Glenarvan rushed out of the ramada. Already the plain had resumed its tranquillity, and all that could be seen of the red wolves was a moving line undulating far away in the distant darkness.

Glenarvan fell to the ground, and clasped his hands despairingly. He looked up at Thalcave.

“Thaouka, good horse.” Thalcave smiled with his accustomed calmness. “Brave boy. He will save himself!”

“And if he falls?” said Glenarvan.

“He will not fall.”

In spite of Thalcave’s confidence, poor Glenarvan spent the rest of the night in tortured anxiety. He seemed quite oblivious now to the danger that had disappeared with the wolf pack. He wanted to chase after Robert, but the Indian stopped him by making him understand the impossibility of their horses overtaking Thaouka. And also that boy and horse had outdistanced the wolves long since, and that it would be useless going to look for them until daylight.

Morning began to dawn at four o’clock. A pale glimmer appeared on the horizon, and pearly drops of dew lay thick on the plain and on the tall grass, already stirred by the breath of day.

The time to leave had come.

“Now!” said Thalcave, “come.”

Glenarvan made no reply, but took Robert’s horse and sprang into the saddle. The next minute both men were galloping at full speed toward the west, in the line in which their companions ought to be advancing.

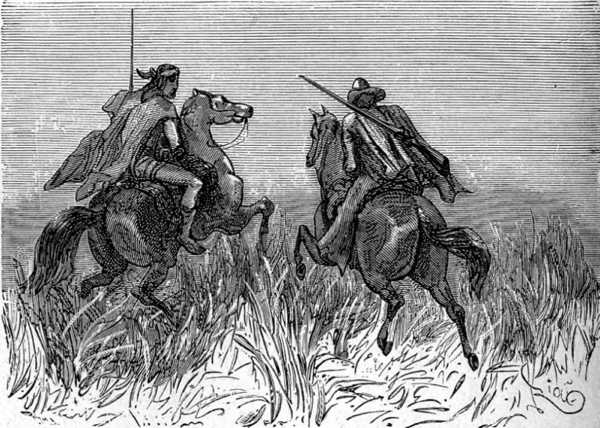

Glenarvan and Thalcave urged their steeds on

They dashed along at a prodigious rate for a full hour, dreading every minute to come across the mangled corpse of Robert. Glenarvan had torn the flanks of his horse with his spurs in his mad haste, when at last gun-shots were heard in the distance at regular intervals, as if fired as a signal.

“It’s them!” exclaimed Glenarvan;

He and Thalcave urged on their steeds to a still quicker pace, until in a few minutes more they came up to the little detachment conducted by Paganel. A cry broke from Glenarvan’s lips, for Robert was there, alive and well, still mounted on the superb Thaouka, who neighed loudly with delight at the sight of her master.

“Oh, my child, my child!” cried Glenarvan, with indescribable tenderness in his tone.

Both he and Robert leaped to the ground, and flung themselves into each other’s arms. Then the Indian hugged the brave boy in his arms.

“He is alive, he is alive,” repeated Glenarvan again and again.

“Yes,” replied Robert, “thanks to Thaouka.”

This great recognition of his favourite’s services was wholly unexpected by the Indian, who was talking to her that minute, caressing and speaking to her, as if human blood flowed in the veins of the proud creature.

Turning to Paganel, he pointed to Robert, and said, “A brave!” and employing the Indian metaphor, he added “His spurs did not tremble!”

But Glenarvan put his arms around the boy and said, “Why wouldn’t you let me or Thalcave run the risk of this last chance of deliverance, my son?”

“My Lord,” replied the boy in tones of gratitude. “Wasn’t it my place to do it? Thalcave has saved my life already, and you — you are going to save my father.”

1. Phosphorescent insects.

2. Now known as Chrysocyon brachyurus, the mane wolf. — DAS