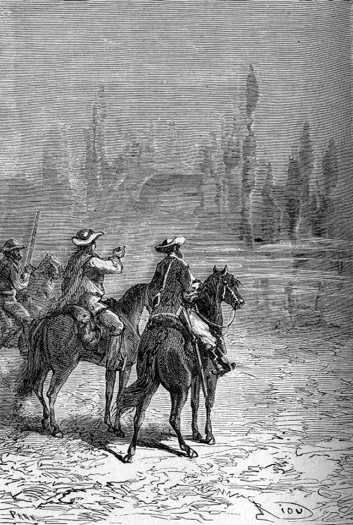

The shot made the whole flock of flamingos take wing

After the first joy of the meeting was over, Paganel, Austin, Wilson, Mulrady, all those who had been left behind, except perhaps for Major MacNabbs, were only conscious of one feeling — they were dying of thirst. Most fortunately for them, the Guamini ran not far off, and about seven in the morning the little troop reached the enclosure on its banks. The area was strewn with the dead wolves, and judging from their numbers, it was evident how violent the attack must have been, and how desperate the resistance.

As soon as the travellers had drunk their fill, they began to demolish the breakfast prepared in the ramada, and did ample justice to the extraordinary viands. The rhea fillets were pronounced first-rate, and the armadillo, roasted in its carapace, was delicious.

“To eat it sensibly,” said Paganel, “would be ingratitude to Providence. We must eat too much.”

And he ate too much of it, and did not hurt himself, thanks to the clear water of the Guamini, which seemed to greatly aid in digestion.

Glenarvan, however, was not going to imitate Hannibal at Capua,1 and at ten o’clock next morning gave the signal to depart. The leather bottles were filled with water, and the day’s march commenced. The horses were so well rested that they were quite fresh again, and kept up a canter almost constantly. The country was not so dry now, and consequently more fertile, but still a desert. No incident occurred of any importance during the 2nd and 3rd of November, and in the evening the travellers, already recovering from the severities of their journey, reached the boundary of the Pampas, and camped for the night on the frontiers of the province of Buenos Aires. They had left Talcahuano Bay on October 14th, twenty-two days ago, and they had come 450 miles.2 almost two thirds of their journey was happily behind them.

Next morning they crossed the conventional line which separates the Argentinian plains from the region of the Pampas. It was here that Thalcave hoped to meet the caciques, in whose hands, he did not doubt to find Harry Grant and his men in slavery.

Of the fourteen provinces composing the Argentinian Republic, that of Buenos Aires is at once the largest and the most populous. It borders the Indian territories of the south, between the 64th and 65th degrees. Its territory is surprisingly fertile. A particularly salubrious climate reigns on this plain covered with grasses and leguminous trees, which extends almost perfectly flat to the foot of the Tandil and Tapalquem mountain ranges.

Since leaving the Guamini, there was marked change in the temperature, to the great relief of the travellers. The average temperature didn’t exceed 17 degrees,3 thanks to the violent and cold winds from Patagonia, which constantly churn the atmospheric waves. Horses and men were glad enough of this, after what they had suffered from the heat and drought, and they advanced with fresh zeal and confidence. But contrary to what Thalcave had said, the whole district appeared uninhabited, or rather abandoned.

Their route often led past or went right through small lagoons, sometimes of fresh water, sometimes of brackish. On the banks and in the shelter of bushes light wrens skipped, and happy larks sang, in company with the tangaras, that rival the colours of the brilliant humming birds. These pretty birds fluttered gaily without paying any attention to the starlings that paraded on the banks with their epaulets and red breasts. Annubis nests swung to and fro in the breeze like a creole hammock on the thorny bushes. Magnificent flamingos stalked the shore like soldiers marching in regular order, and spread out their fire coloured wings. Thousands of their cone shaped nests, about a foot high, formed a complete town. The flamingos did not disturb themselves in the least at the approach of the travellers, but this did not suit Paganel.

“For a long time,” he said to the Major, “I have wanted to see a flamingo flying.”

“Good!” said the Major.

“Now, since I find the occasion, I shall take advantage of it.”

“Enjoy yourself, Paganel.”

“Come with me, Major, and you too, Robert. I want witnesses.”

And Paganel, letting the rest of the band go on, led Robert and the Major to the troop of birds.

The shot made the whole flock of flamingos take wing

As soon as they were near enough, Paganel fired a shotgun, only loaded with powder, for he would not shed the blood of a bird uselessly. The shot made the whole assemblage take wing, while Paganel watched them attentively through his spectacles.

“Well, did you see them fly?” he asked the Major.

“Certainly I did. I could not help seeing them, unless I had been blind.”

“Good. And did you think they resembled feathered arrows when they were flying?”

“Not in the least.”

“Not a bit,” added Robert.

“I was sure of it,” said the scientist, with a satisfied air. “And yet the very proudest of modest men, my illustrious countryman, Chateaubriand, made the inaccurate comparison between flamingos and arrows. Oh, Robert, comparison is the most dangerous figure in rhetoric that I know. Mind you avoid it all your life, and only employ it in a last extremity.”

“Are you satisfied with your experiment?” asked MacNabbs.

“Delighted.”

“And so am I. But we had better push on now, for your illustrious Chateaubriand has put us a mile behind.”

On rejoining their companions, Paganel found Glenarvan busily engaged in conversation with the Indian, whom he did not seem to understand. Thalcave often stopped to observe the horizon, each time with a puzzled expression on his face. Glenarvan had been unable to determine the cause, without his usual interpreter. As soon as he saw the scientist return, he called to him.

“Come along, friend Paganel. Thalcave and I can’t understand each other at all.”

After a few minute’s talk with the Patagonian, the interpreter turned back to Glenarvan. “Thalcave is quite astonished by a fact which he finds truly bizarre.”

“Which?”

“That there are no Indians, nor even traces of any to be seen in these plains, for they are generally thick with companies of them, either driving along cattle stolen from the estancias, or going to the Andes to sell their zorillo rugs and braided leather whips.”

“And what does Thalcave think is the reason?”

“He does not know; he is astonished and that’s all.”

“But what Indian people did he reckon on meeting in this part of the Pampas?”

“Just the very ones who had the foreign prisoners in their hands, the natives under the rule of the Caciques Calfoucoura, Catriel, or Yanchetruz.”

“Who are these caciques?”

“Band leaders who were all-powerful thirty years ago, before they were driven beyond the sierras. Since then they have submitted as much as an Indian can submit, and they scour the plains of the Pampas and the province of Buenos Aires. I quite share Thalcave’s surprise at not discovering any traces of them in regions which they usually infest as salteadores.”4

“And what must we do then?”

“I’ll go and ask him,” replied Paganel.

After a brief conversation he returned.

“This is his advice, which seems sound to me. He says we had better continue our route to the east as far as Fort Independence, and if we don’t get news of Captain Grant there we shall hear, at any rate, what has become of the Indians of the Argentinian plains.”

“Is Fort Independence far away?” asked Glenarvan.

“No, it is in the Sierra Tandil, about sixty miles.”

“And when shall we arrive?”

“The day after tomorrow, in the evening.”

Glenarvan was quite disconcerted by this circumstance. Not to find an Indian where there were generally too many, was so unusual that there must be some serious cause for it. But worse still if Harry Grant were a prisoner in the hands of any of those tribes, had he been dragged away with them to the north or south? This doubt left Glenarvan uneasy. He felt that, cost what it might, they must not lose his track, and therefore decided to follow the advice of Thalcave, and go to the village of Tandil. There, at least, they would find someone to talk to.

About four o’clock in the evening a hill, which seemed a mountain in so flat a country, was sighted in the distance. This was Sierra Tapalquem, at the foot of which the travellers camped that night.

The passage of this mountain the next day was the easiest thing in the world. They followed sandy ripples up gently sloping terrain. Such a mountain could not be taken seriously by people who had crossed the Andes, and the horses barely reduced their speed. They passed the deserted fort of Tapalquem — the first of the chain of forts which defended the southern frontiers from Indian marauders — at noon. But to the increasing surprise of Thalcave, they did not come across even the shadow of an Indian. However, about the middle of the day three flying horsemen, well mounted and well armed, came in sight, gazed at them for an instant, and then sped away with incredible speed. Glenarvan was furious.

“Gauchos,” said the Patagonian, designating them by the name which had caused such a fiery discussion between the Major and Paganel.

“Ah! the Gauchos,” said MacNabbs. “Well, Paganel, the north wind is not blowing today. What do you think of those fellows yonder?”

“I think they look like regular bandits.”

“And how far is it from looking to being, my good geographer?”

“Only just a step, my dear Major.”

Paganel’s admission was received with a general laugh, which did not in the least disconcert him. He went on talking about the Indians however, and made this curious observation:

“I have read somewhere,” he said, “that the Arabs have a peculiar expression of ferocity in their mouths, while human expression is in the eye. Well, in the wild American, it’s the complete opposite. These people have a particularly nasty eye.” No physiognomist by profession could have better characterized the Indian race.

But desolate as the country appeared, Thalcave was on his guard against surprises, and gave orders to his party to form themselves in a close platoon. It was a useless precaution, however; for that same evening, they camped for the night in an immense tolderia, where the Cacique Catriel ordinarily gathered his bands of natives, which they not only found perfectly empty, but which the Patagonian declared, after he had examined it all around, must have been uninhabited for a long time.

Next day, the first estancias5 of the Sierra Tandil came in sight. Thalcave resolved not to stop at any of them, but to go straight on to Fort Independence, where he wished to inquire, particularly, on the peculiar situation of this abandoned country.

The trees, so rare since the Cordillera, reappeared, most planted after the arrival of the Europeans on the American territory. There were azedarachs, peach trees, poplars, willows, and acacias, which grew quickly and well by themselves. They usually surrounded the corrales: large, fenced, cattle enclosures. There, thousands of oxen, sheep, cows, and horses — branded with their owner’s mark — were grazing and fattening, while large, vigilant and numerous dogs watched over them. The slightly saline soil at the foot of the mountains was well suited to herds and produces excellent forage: well suited for the establishment of the estancias, which are directed by a majordomo and a foreman, with a team of four peons for a thousand head of cattle.

These people lead the life of the great shepherds of the Bible. Their flocks are as numerous — perhaps more numerous — than those which filled the plains of Mesopotamia. But here the family is wanting the Shepherd, and the great estancers of the Pampas are rude cattle merchants, nothing like the patriarchs of biblical times.

This is what Paganel explained very well to his companions, and on this subject he engaged in an interesting anthropological discussion on the comparison of races. He even managed to entice the Major into the discussion.

Paganel had occasion to observe mirages

Paganel also had occasion to observe the curious effect of mirages very common in these flat plains: the estancias, from afar, resembled large islands. The poplars and willows surrounding them seemed to be reflected in clear water, which receded before the footsteps of travellers, but the illusion was so perfect that the eye could not get used to it.

During the day of November 6th, they passed several estancias, and also one or two saladeros. It is here that the cattle, after having been fattened in the midst of succulent pastures, are brought to be butchered. The saladero, as its name suggests, is the place where meat is salted. This repugnant work begins at the end of spring. The “saladeros” will collect animals from a corral. They seize them with a lasso, which they handle skilfully, and lead them to the saladero. There, oxen, bulls, cows, and sheep are slaughtered in the hundreds, skinned and dried. Often the bulls do not let themselves be taken without a fight. The flayer then becomes a bullfighter, and this dangerous craft, he does with alacrity and, it must be said, an unusual ferocity. In short, this butchery presents a dreadful spectacle.

Nothing is as repulsive as the surroundings of a saladero. These horrible enclosures are surrounded by a fetid stench. The ferocious cries of flayers, sinister barking of dogs, and prolonged screams of dying animals emanate from them, while the urubus and auras — great vultures of the Argentinian plains — come from thousands of miles around to compete with the butchers for the still stirring debris of their victims. But at the moment the saladeros were silent, peaceful and uninhabited. The season for these immense killings had not yet come.

Thalcave pressed the march; he wished to arrive at Fort Independence that evening. The horses, excited by their masters and following the example of Thaouka, galloped through the tall grasses of the plain. They passed several farms crenellated and defended by deep moats; the main house had a terrace, from the top of which the inhabitants can shoot the bandits of the plain with military precision. Glenarvan might have found the information he was seeking at one of these, but the surest way was to arrive at the village of Tandil. They did not stop. They crossed the Rio de los Huesos, and a few miles farther on, the Chapaleofu. Soon the first grassy slopes of the Sierra Tandil came under their horses’ hooves, and an hour later the village appeared at the bottom of a narrow gorge, dominated by the crenellated walls of Fort Independence.

1. According to Livy, rather than capitalizing on his victory at Cannae by following it up with an immediate attack on a demoralized Rome, Hannibal retired to the city of Capua to celebrate his victory, and thus squandered his chance to win the Second Punic War. Modern historians tend to discount this theory — DAS

2. About 180 leagues. (720 kilometres — DAS)

3. 63° Fahrenheit. — DAS

4. Bandits.

5. The great cattle stations of the Argentinian plain.