It was a dozen children and young boys who were drilling

The Sierra Tandil rises a thousand feet above sea level. It is a primordial chain — that is to say, it came prior to all organic and metamorphic creation. Its texture and composition have gradually changed under the influence of internal heat. It is formed of semi-circular ridges of gneiss hills, covered with fine short grass. The district of Tandil, to which it has given its name, includes all the south of the Province of Buenos Aires, and terminates in a river which conveys north all the rios that are born on its slopes.

This district contains about four thousand inhabitants, and its chief town is the village of Tandil, situated at the foot of the northern ridge of the sierra, under the protection of Fort Independence. It is favourably positioned on the stream of Chapaleofu. Of special interest to Paganel, this village was populated by French Basques and Italians. It was France that founded the first European settlements in this lower part of the Plata. In 1828, Fort Independence — intended to protect the country against the repeated invasions of the Indians — was built by the Frenchman Parachappe. Alcide d’Orbigny, best known for his study and description of all the southern countries of South America accompanied him on this undertaking.

Tandil occupied a strategic location. Large ox carts, called galeras, built for the plains roads, can travel between the village and Buenos Aires in twelve days. This allows for active commerce. The village sends the city the cattle of its estancias, the saltings of its saladeros, and various products of the Indians, such as cotton and wool fabrics, leatherwork, and other things. Tandil consists of a number of fairly comfortable houses, schools to educate its people of this world, and churches to educate them of the other.

Paganel, after imparting this information to his companions, added that information could not be lacking in the village. The fort, moreover, was always occupied by a detachment of national troops. Glenarvan put their horses in the stable of a fonda of rather good appearance, then he, Paganel, MacNabbs, and Robert, under the direction of Thalcave, proceeded to Fort Independence.

After making a short ascent up the sierra, they reached the postern gate, carelessly guarded by an Argentinian sentinel. They passed through without difficulty, which indicated either extreme negligence or extreme confidence.

It was a dozen children and young boys who were drilling

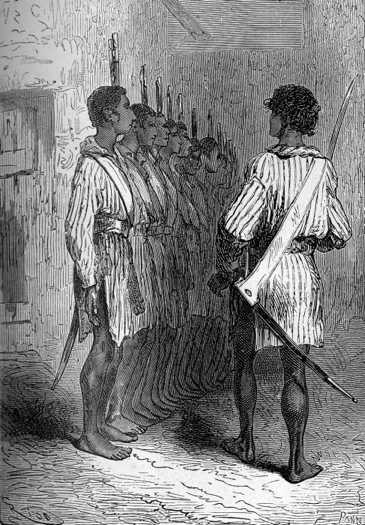

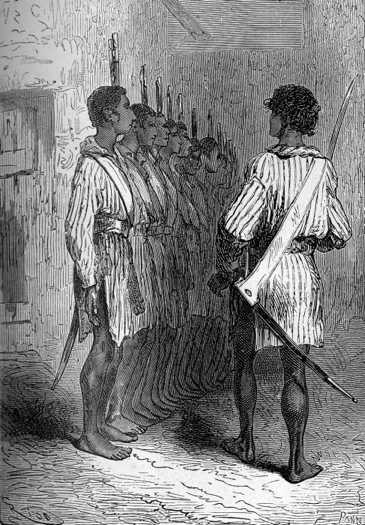

Some soldiers were exercising on the parade ground of the fort. The oldest of these soldiers was twenty, and the youngest seven. As a matter of fact, it was a dozen children and young boys who were drilling, very nicely. Their uniform consisted of a striped shirt tied at the waist with a leather belt, without trousers, breeches, or Scottish kilt. The mildness of the temperature made this uniform quite practical, and Paganel had a good opinion of a government that wasn’t stingy with stripes. Each of these young boys carried a percussion rifle and a sabre, the sword too long and the rifle too heavy for the little ones. All had swarthy faces, and a certain family resemblance. The corporal instructor looked like them, too. It must have been, and indeed it was, twelve brothers parading under the orders of the thirteenth.

Paganel was not surprised. He knew his Argentinian statistics, and knew that the average number of children exceeds nine per household. But what greatly surprised him was to see these children perform the principal movements of loading their rifles with perfect precision, twelve times. Often the corporal’s commands were even in the native language of the learned geographer.

“That’s exceptional,” he said.

But Glenarvan had not come to Fort Independence to watch toddlers do military exercises, let alone to deal with their nationality or origin. He did not give Paganel time to be surprised any more, and he begged him to ask for the head of the garrison. Paganel complied, and one of the Argentinian soldiers went to a small barracks building.

A few minutes later the Commandant appeared in person. He was a vigorous man about fifty years old, of military bearing, with greyish hair, and an imperious eye — as far as one could see through the clouds of tobacco smoke which escaped from his short pipe. His walk reminded Paganel of the old noncommissioned officers of his own country.

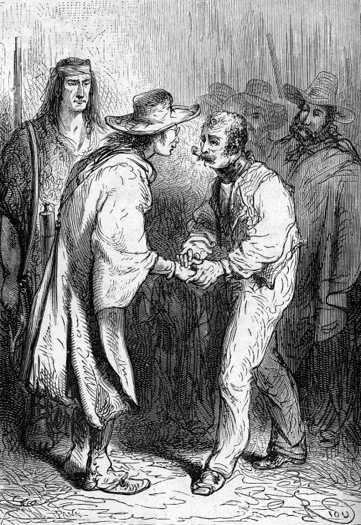

Thalcave, addressing the Commandant, introduced him to Lord Glenarvan and his companions. While Thalcave was speaking, the commander kept staring at Paganel in a rather embarrassing manner. The scientist could not understand what the soldier meant by it, and was just about to question him, when the commander came forward, and without ceremony, seized both his hands, and said in a joyful voice, in the geographer’s own language:

“Un Français?”

“Oui! Un Français!” said Paganel.

“Ah! Enchanté! Bienvenu! Bienvenu!” The Commandant shook Paganel’s hand with alarming vigour. “Suis Français aussi,” he added.

“Ah! Enchanté! Bienvenu! Bienvenu!” The Commandant shook Paganel’s hand with alarming vigour. “Suis Français aussi,” he added.

“Is he a friend of yours, Paganel?” asked the Major.

“Parbleu!” said Paganel, somewhat proudly. “I have friends in all five regions of the world!”

After he had succeeded in disengaging his hand, though not without difficulty, from the living vice in which it was held, a lively conversation ensued. Glenarvan would gladly have put in a word about the business at hand, but the soldier related his entire history, and was not in a mood to stop until he was done. It was plain to see that this good man must have left France many years back, for his mother tongue had grown unfamiliar, and if he had not forgotten the words he certainly did not remember how to put them together. His speech was more like the creole of a French colony. Indeed, they were quick to learn that the commander of Fort Independence was a French sergeant, an old comrade of Parachappe.

He had not left the fort since it had been built in 1828, and he now commanded it with the consent of the Argentinian government. He was a man about fifty years of age, a Basque, and his name was Manuel Ipharaguerre, so that he was almost a Spaniard. A year after his arrival in the country he was naturalized, took service in the Argentinian army, and married an Indian girl, who was now nursing twin, six month old babies — two boys, be it understood, for the good wife of the sergeant would have never thought of presenting her husband with girls. Manuel could not conceive of any state but a military one, and he hoped in due time, with the help of God, to offer the Republic a whole company of young soldiers.

“Did you see them? Charming! Good soldiers are José, Juan, and Miquele! Pepe, seven year old Pepe, can handle a gun!”

Pepe, hearing himself complimented, brought his two little feet together, and presented arms with perfect grace.

“He’ll get on!” added the sergeant. “He’ll be Colonel Major or Brigadier General some day!”

Sergeant Manuel seemed so enchanted that it would have been useless to express a contrary opinion, either to the profession of arms or the probable future of his children. He was happy, and as Goethe says, “Nothing that makes us happy is an illusion.”

All this talk took up a quarter of an hour, to the great astonishment of Thalcave. The Indian could not understand how so many words could come out of one throat. No one interrupted the Commandant, but as a sergeant, even a French sergeant, had stop talking at some point, Manuel finally fell silent, but not without obliging his guests to follow him to his house and be presented to Madame Ipharaguerre who was indeed “a good woman”.

Then, and not until then, did he ask his guests what gave him the honour of their visit. Now or never was the moment to explain, and Paganel, seizing the chance at once, began an account of their journey across the Pampas, and ended by asking why the Indians had abandoned the country.

“Ah! … nobody!” said the Sergeant, shrugging his shoulders. “Really! … No one! … and us, arms crossed … nothing to do!”

“But why?”

“War.”

“War?”

“Yes, civil war— “

“Civil war?” asked Paganel, dropping into the same sort of creole as the sergeant.

“Yes, war between the Paraguayans and Buenos Aires,” replied the sergeant.

“Well?”

“Well, Indians all in the north, in the rear of General Flores. Indian looters, loot”

“But where are the caciques?”

“Caciques are with them.”

“What! Catriel?”

“No Catriel.”

“And Calfoucoura?”

“Point Calfoucoura.”

“And Yanchetruz?”

“More Yanchetruz.”

The reply was reported to Thalcave, who shook his head and gave an approving look. The Patagonian was either unaware of, or had forgotten that civil war was decimating the two parts of the republic — a war which would ultimately lead to the intervention of Brazil. The Indians have everything to gain by these internecine strifes, and would not lose such fine opportunities for plunder. There was no doubt the sergeant was right in assigning the war in the north as the cause of the forsaken appearance of the plains.

But this circumstance upset all Glenarvan’s plans, for if Harry Grant was a prisoner in the hands of the caciques, he must have been dragged north with them. How and where should they ever find him if that were the case? Should they attempt a perilous and almost useless journey to the northern border of the Pampas? It was a serious question which would need to be well debated.

However, there was an important question that could still be asked of the sergeant; and it was the Major who thought of it, while the others looked at each other in silence.

“Has the sergeant heard whether any Europeans were being held prisoners in the hands of the caciques?”

Manuel looked thoughtful for a few minutes, like a man trying to ransack his memory.

“Yes,” he said finally.

“Ah!” said Glenarvan, catching at the fresh hope.

They all eagerly crowded around the Sergeant. “Tell us, tell us!” they said eagerly.

“A few years ago,” replied Manuel. “Yes … that’s it … European prisoners … but never seen…”

“A few years,” said Glenarvan. “You are mistaken. The date of the sinking is precise. The Britannia was wrecked in June, 1862, less than two years ago.”

“Oh, more than that, My Lord.”

“Impossible!” said Paganel.

“If really! It was when Pepe’s birth. It was two men.”

“No, three!” said Glenarvan.

“Two!” replied the Sergeant, in a positive tone.

“Two?” echoed Glenarvan, very surprised. “Two Englishmen?”

“No, no. Who speaks of English? No … a Frenchman and an Italian.”

“An Italian who was massacred by the Poyuches?” exclaimed Paganel.

“Yes! and I have since learned … Frenchman saved.”

“Saved!” cried young Robert, hanging on the sergeant’s every word.

“Yes, saved from the hands of the Indians,” said Manuel.

Paganel struck his forehead with an air of desperation.“Ah! I understand! It is all clear now; everything is explained.”

“But what is it?” asked Glenarvan, as worried as impatient.

“My friends,” replied Paganel, taking both Robert’s hands in his own, “we must resign ourselves to a grave disappointment. We have been on a wrong track. The prisoner mentioned is not Captain Grant at all, but one of my own countrymen; and his companion, Marco Vazello, who was murdered by the Poyuches. The Frenchman was dragged across the Pampas several times by the cruel Indians. Often as far as the shores of the Colorado, but he managed at length to make his escape, and return to France. Instead of following the track of Harry Grant, we have fallen on that of young Guinnard.”1

A profound silence greeted this statement. The error was palpable. The details given by the sergeant, the nationality of the prisoner, the murder of his companion, his escape from the hands of the Indians, all evidenced the fact.

Glenarvan looked at Thalcave with a crestfallen face.

The Indian, turning to the sergeant, asked “Have you ever heard of three captive Englishmen?”

“Never,” replied Manuel. “We would have known of them at Tandil, I am sure. No, it cannot be.”

Glenarvan, after this answer, had nothing more to do at Fort Independence. He and his friends withdrew, after thanking the sergeant and exchanging a few handshakes with him.

Glenarvan was distraught at this complete reversal of his hopes, and Robert walked silently beside him, with his eyes full of tears. Glenarvan could not find a word of comfort to say to him. Paganel gesticulated and talked to himself. The Major never opened his mouth, nor Thalcave, whose Indian self esteem seemed quite wounded by having lost his way on a false trail. No one, however, thought of reproaching him for such an excusable error.

They went back to the fonda.

Supper was a gloomy affair. Not one of these courageous men regretted the trials they had so heedlessly endured, or the dangers they had run, but they all felt that their hope of success was gone. Was there any chance of coming across Captain Grant between the Sierra Tandil and the sea? No. Sergeant Manuel must certainly have heard if any prisoners had fallen into the hands of the Indians on the Atlantic coast. Any event of this nature would have attracted the notice of the Indians who trade between Tandil and Carmen, at the mouth of the Rio Negro. The traders of the Argentinian plain traffic in gossip as much as goods. If such a thing had happened, all would know of it. The only thing to do now was to get to the planned rendezvous with the Duncan at Point Medano, as quickly as possible.

Paganel asked Glenarvan to let him have the document again, to see if he could discover how they had been led astray. He re-read it with poorly hidden anger, trying to extract some new meaning out of it.

“Yet nothing can be clearer,” said Glenarvan. “It gives the date of the shipwreck, and the manner, and the place of the captivity in the most categorical manner.”

“No, it does not!” Paganel struck the table with his fist. “A hundred times, no! Since Harry Grant is not in the Pampas, he is not in America. But this document must say where he is, and it will say it, my friends, or my name is not Jacques Paganel!”

1. Auguste Guinnard was, in fact, a prisoner of the Poyuches Indians for three years, from 1856 to 1859. He endured terrible trials with extreme courage, and finally managed to escape by crossing the Andes at the Upsallata Pass. He saw France again in 1861, and is now one of the colleagues of the Honourable Paganel at the Geographic Society.