A falling, rising, rushing, incoherent mixture of frightened animals, fleeing with a frightful speed.

A Distance of 150 miles separates Fort Independence from the shores of the Atlantic.1 Unless there were unforeseen delays, which were unlikely, Glenarvan would rejoin the Duncan in four days. But to come back without Captain Grant, after having failed so completely in his search, was something he was loath to do. He gave no orders for departure the next day. The Major took it upon himself to have the horses saddled, renew their provisions, and to establish the bearings of the road. Thanks to his activity the little troop descended the grassy slopes of Sierra Tandil the next morning at eight o’clock.

Glenarvan, with Robert at his side, galloped along without saying a word. His bold, determined nature made it impossible to take this failure calmly. His heart throbbed as if it would burst, and his head was burning. Paganel, annoyed by the difficulty, returned to the words of the document, trying to discover some new meaning. Thalcave was perfectly silent, and left Thaouka to lead the way. The Major, always confident, remained solid at his post, like a man on whom discouragement takes no hold. Tom Austin and his two sailors shared the dejection of their master. A timid rabbit happened to run across their path, and the superstitious Scots looked at each other in dismay.

“A bad omen,” said Wilson.

“Yes, in the Highlands,” said Mulrady.

“What’s bad in the Highlands is not better here,” said Wilson sententiously.

By noon they had crossed the Sierra Tandil, and descended into the undulating plains stretching to the sea. At each step clear rios watered this fertile land, and lost themselves among the tall grasses. The ground had once more become completely level, like the ocean after a storm. The last mountains of the Argentinian Pampas were behind them, and a long carpet of greenery unrolled itself over the monotonous meadow. It was easy to see the fertility of this land in the rich abundance of its pastures and their somber greenness.

The weather had been fine until then. But today the sky presented anything but a reassuring appearance. The heavy vapours generated by the high temperature of the preceding days hung in thick clouds which promised to empty themselves in torrents of rain. Moreover, the vicinity of the Atlantic, and the prevailing west wind, made the climate of this country particularly humid.

That day, at least, the clouds did not burst, and in the evening, after a brisk gallop of forty miles, the horses stopped on the brink of a deep canadas, an immense natural trench filled with water. No shelter was near, and ponchos had to serve both for tents and coverlets as each man lay down and fell asleep beneath the threatening sky, but the rains still did not come.

Next day as the plain lowered, the presence of underground water became still more noticeable. Moisture oozed from every pore of the ground. Soon large ponds, some just beginning to form, and some already deep, lay across the road to the east. As long as they had only to deal with lagunas, well circumscribed stretches of water unencumbered with aquatic plants, the horses could get through well enough, but when they encountered moving sloughs called penganos, it was harder work. Tall grass clogged them, and it wasn’t possible to recognize the hazard until you were already in it.

These bogs had already proved fatal to more than one living thing, for Robert, who had gone forward by half a mile, came rushing back at full gallop.

“Monsieur Paganel, Monsieur Paganel!” he called. “A forest of horns!”

“What!” exclaimed the geographer; “you have found a forest of horns?”

“Yes, yes, or at least a grove.”

“A grove!” Paganel, shrugged his shoulders. “My boy, you are dreaming.”

“I am not dreaming, and you will see for yourself,” said Robert. “This is a strange country. They sow horns, and they sprout up like wheat. I wish I could get some of the seed.”

“The boy is really speaking seriously,” said the Major.

“Yes, Major, and you will soon see clearly.”

Robert was not mistaken, for presently they found themselves in front of an immense field of horns, regularly planted and stretching far out of sight. It was a complete copse, low and close packed, but strange.

“Well,” said Robert.

“This is peculiar,” said Paganel, and he turned around to question Thalcave on the subject.

“The horns come out of the ground,” said Thalcave, “but the oxen are down below.”

“What?” exclaimed Paganel. “Is there a whole herd that has mired in this mud?”

“Yes,” said the Patagonian.

In fact, an immense herd had died under this soil, which had been liquified by the vibration of its passage. Hundreds of oxen had just perished, side by side, suffocated in the vast pothole. This event, which sometimes occurs in the plains of Argentina, could not be ignored by the Indian, and it was a warning to be taken seriously. The immense hecatomb, which would have satisfied the most exacting gods of antiquity, was circled around, and an hour later the field of horns was left two miles behind.

Thalcave was somewhat anxiously observing a state of things which appeared unusual to him. He frequently stopped and raised himself on his stirrups and looked around. His great height gave him a commanding view of the whole horizon, but perceiving nothing that could enlighten him, he quickly resumed his seat and went on. About a mile further he stopped again, and leaving the straight route, made a circuit of some miles north and south, and then returned and fell back in his place at the head of the troop, without saying a syllable as to what he hoped or feared. This strange behaviour, repeated several times, intrigued Paganel, and worried Glenarvan. At last, at Glenarvan’s request, he asked the Indian about it.

Thalcave replied that he was astonished to see the plains so saturated with water. Never, to his knowledge, since he had followed the calling of guide, had he found the ground in this waterlogged condition. Even in the rainy season, the Argentinian plains had always been passable.

“But what is the source of all this water?” said Paganel.

“I do not know, and when I do…”

“Do the rios of the Sierra, swollen by heavy rain, never overflow their banks?”

“Sometimes.”

“And now, maybe?”

“Perhaps.”

Paganel was obliged to be content with this unsatisfactory reply, and went back to Glenarvan to report the result of his conversation.

“And what does Thalcave advise us to do?” said Glenarvan.

“What should we do?” he asked him.

“Go on quickly,” said Thalcave.

This was easier said than done. The horses rapidly tired treading over ground that gave way and oozed water at every step. This part of the plain could be likened to an immense bottom, where the invading waters were quickly accumulating. A flood would immediately transform this basin into a lake. It was important to cross these lands without delay,

They quickened their pace, but could not go fast enough to escape the water, which rolled in great sheets at their feet. About two o’clock the clouds burst, and cascades of tropical rain poured down upon the plain. There was no way to escape this deluge, and it was better to receive it stoically. Their ponchos were dripping; their hats overflowed like a roof whose gutters are engorged; the fringe of the recados seemed made of liquid nets. The horse’s hooves struck up torrents from the ground, and the horsemen, splashed by their mounts, rode in a double shower which came at once from the earth and the sky.

In this drenched, cold, and worn out state, they came to a miserable rancho at evening. Only desperate people could call it a shelter, and only travellers at bay would even think of entering it; but Glenarvan and his companions had no choice, and were glad enough to burrow in this wretched hovel, though it would have been despised by even a poor Indian of the Pampas. A miserable fire of grass was kindled, which gave out more smoke than heat, and was very difficult to keep alight, as the torrents of rain which dashed against the outside of the ruined cabin found their way within and fell down in large drops from the roof. Twenty times over the fire would have been extinguished if Mulrady and Wilson had not kept off the water.

The supper was a dull meal, and neither appetizing nor reviving. Only the Major seemed to eat with any relish. The impassive MacNabbs was superior to all circumstances. Paganel, Frenchman as he was, tried to joke, but the attempt was a failure.

“My jests are damp,” he said. “They miss fire.”

The only consolation in such circumstances was to sleep, and accordingly each one lay down and endeavoured to find in slumber a temporary forgetfulness of his discomforts and fatigues. The night was stormy, and the planks of the rancho cracked before the blasts as if every instant they would give way. The poor horses outside, exposed to all the inclemency of the weather, were making piteous moans, and their masters were suffering quite as much inside the ruined hut. Sleep overpowered them at last. Robert was the first to close his eyes and lean his head against Glenarvan’s shoulder, and soon all the rest were soundly sleeping under the protection of God.

It seems that God made good guard, because the night ended without accident. No one stirred until Thaouka woke them by tapping vigorously against the rancho with her hoof. She knew it was time to start, and at a push could give the signal as well as her master. They owed the faithful creature too much to disobey her, and set off immediately.

The rain had abated, but floods of water still covered the saturated ground. Puddles, marshes and ponds overflowed and formed immense banados of untrustworthy depth. Paganel, on consulting his map, came to the conclusion that the rios Grande and Vivarota, into which the water from the plains generally runs, must have merged into one bed several miles wide.

Extreme haste was imperative, for all their lives depended on it. Should the inundation increase, where could they find refuge? Not a single elevated point was visible on the whole circle of the horizon, and on such level plains water would sweep along with fearful rapidity.

The horses were spurred on to the utmost, and Thaouka led the way, bounding over the water as if it had been her natural element. Certainly she might justly have been called a sea-horse — better than many of the aquatic animals who bear that name.

Suddenly, about ten o’clock, Thaouka gave signs of violent agitation. She kept turning around toward the wide plains of the south, neighing continually, and snorting with wide open nostrils. She reared violently, and Thalcave had some difficulty in keeping his seat. The foam from her mouth was tinged with blood from the action of the bit, pulled tightly by her master’s strong hand, and yet the fiery animal would not be still. Had she been free, her master knew she would have fled away northward as fast as her legs would have carried her.

“What is the matter with Thaouka?” asked Paganel. “Is she bitten by the leeches? They are very voracious in the Argentinian streams.”

“No,” replied the Indian.

“Is she frightened at something, then?”

“Yes, she scents danger.”

“What?”

“I do not know.”

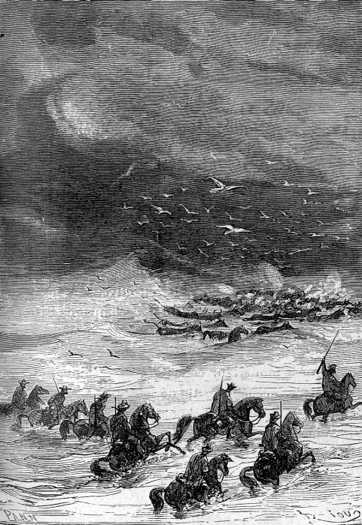

A falling, rising, rushing, incoherent mixture of frightened animals, fleeing with a frightful speed.

If the eye did not yet reveal the danger that Thaouka felt, the ear, at least, could already be aware of it. A low murmur, like the sound of a rising tide, was heard beyond the limits of the horizon. The wind was gusty and wet with mist. The birds, fleeing some unknown phenomenon, traversed the air. The horses, submerged to mid-leg, felt the first thrusts of the current. Soon a tremendous noise: a roaring, neighing, bleating sounded half a mile south, and huge herds appeared. A falling, rising, rushing, incoherent mixture of frightened animals, fleeing with a frightful speed. It was scarcely possible to distinguish them amidst the liquid eddies raised in their course. One hundred of the largest of whales could not have pushed up more violent waves in the ocean.

“Anda, anda!”2 shouted Thalcave, in a voice like thunder.

“What is it, then?” asked Paganel.

“Flood! Flood!” said Thalcave, spurring his horse, which he launched northward.

“Flooding!” cried Paganel, flying with his companions after Thaouka.

It was past time, for about five miles south an immense tsunami was advancing over the plain, and changing the whole country into an ocean. The tall grass disappeared before it as if cut down by a scythe. Tufts of mimosas, torn off by the current were pushed ahead of the wave, advancing with irresistible power. Of course there had been a break in the barrancas of the great rivers of Pampasia, and perhaps the waters of Rio Colorado to the north and Rio Negro to the south met now in a common bed.

The wave was speeding on with the rapidity of a race-horse, and the travellers fled before it like a cloud before a storm-wind. They looked in vain for some refuge. The sky and the water were confused on the horizon. The terrified horses galloped so wildly along that the riders could hardly keep their saddles. Glenarvan often looked back, and saw the water overtaking them.

“Anda, anda!” shouted Thalcave.

They spurred the poor horses on until blood ran from their lacerated sides, and traced the water in long red threads. They stumbled over crevasses in the ground, or got entangled in the hidden grass below the water. They fell, and were pulled up, only to fall again and again, and be pulled up again and again. The level of the water was rising. Long ripples announced the assault of this wave, which raised its foaming head less than two miles behind them.

This ultimate struggle with the most terrible of elements lasted for a quarter of an hour. The fugitives could not tell how far they had gone, but, judging by their speed, the distance must have been considerable. The poor horses were chest high in water now, and could only advance with extreme difficulty. Glenarvan, Paganel, Austin, all thought themselves doomed to the horrible death of those poor souls lost at sea. The horses were swiftly getting out of their depth, and six feet of water would be enough to drown them.

It is necessary to give up painting the poignant anxieties of these eight men overtaken by a rising tide. They felt helpless to fight against this cataclysm of nature, superior to human efforts. Their salvation was no longer in their hands.

Five minutes later, and the horses were swimming; the current alone carried them along with tremendous force, and with a swiftness equal to their fastest gallop. They must have been moving at fully twenty miles an hour.

All hope of delivery seemed impossible, when the Major suddenly called out.

“A tree!”

“A tree?” exclaimed Glenarvan.

The monstrous wave, forty feet high, swept over them

“There, there!” Thalcave pointed to a species of gigantic walnut, which raised its solitary head above the waters, a mile to the north.

His companions needed no urging now; this tree, so unexpectedly discovered, must be reached at all costs. The horses very likely might not be able to get to it, but the men at least might be saved. The current was bearing them right to it.

Just at that moment Tom Austin’s horse gave a smothered neigh and disappeared. His master, freeing his feet from the stirrups, began to swim vigorously.

“Hang on to my saddle,” called Glenarvan.

“Thank you, Your Honour, but I have good stout arms.”

“How’s your horse, Robert?” asked Glenarvan, turning to young Grant.

“Very well, My Lord! He swims like a fish.”

“Look out!” shouted the Major, in a stentorian voice.

The warning was scarcely spoken before the enormous tsunami arrived. A monstrous wave forty feet high, swept over the fugitives with a terrible noise. Men and animals all disappeared in a whirl of foam. A liquid mass, weighing several millions of tons, engulfed them in its seething waters.

When the tsunami had passed, the men reappeared on the surface, and counted each other rapidly; but all the horses, except Thaouka, who still bore her master, had disappeared forever.

“Courage, courage,” repeated Glenarvan, supporting Paganel with one arm, and swimming with the other.

“I can manage! I can manage!” said the worthy scholar. “I am even not sorry—”

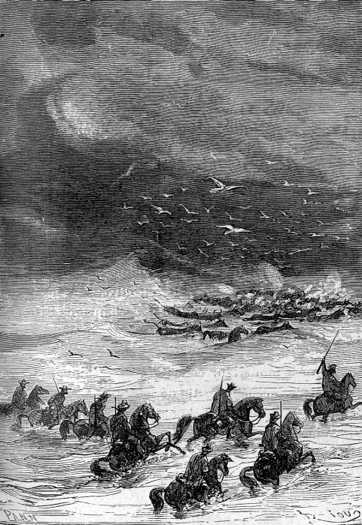

Thaouka was being rapidly carried away by the current

But no one ever knew what he was not sorry about, for the poor man was obliged to swallow down the rest of his sentence with half a pint of muddy water. The Major advanced quietly, making regular strokes, worthy of a life guard. The sailors took to the water like porpoises, while Robert clung to Thaouka’s mane, and was carried along with her. The noble animal swam superbly, instinctively making straight for the tree.

The tree was only forty yards off, and in a few minutes the whole party had safely reached it. If not for this refuge they must all have perished in the flood.

The water had risen to the top of the trunk, just to where the parent branches forked out. It was easy to cling to it. Thalcave abandoned his horse, and climbed into the tree, carrying Robert with him. Then his mighty arms helped pull all the exhausted swimmers to safety.

But Thaouka was being rapidly carried away by the current. She turned her intelligent face toward her master, and, shaking her long mane, neighed to call him.

“Are you going to forsake her, Thalcave?” asked Paganel.

“Me?” cried the Indian.

He plunged down into the tumultuous waters, and came up again twenty yards off. A few instants afterward his arms were around Thaouka’s neck, and master and steed were drifting together toward the misty horizon to the north.

1. About 60 leagues. (240 kilometres — DAS)

2. Quick! Quick!