They dried themselves, and hung their ponchos in the breeze

The tree in which Glenarvan and his companions had just found refuge resembled a walnut, having the same glossy foliage and rounded form. In reality, however, it was the ombú, which grows solitarily on the Argentinian plains. The enormous and twisted trunk of this tree is planted firmly in the soil, not only by its great roots, but still more by its vigorous shoots, which fasten it down in the most tenacious manner. This was how it stood proof against the shock of the tsunami.

This ombú was one hundred feet tall, and its shadow covered a circumference of sixty fathoms. Its immense canopy rested on three great boughs which trifurcated from the top of the six foot wide trunk. Two of these rose almost perpendicularly, and supported an immense parasol of foliage, the branches of which were so crossed and intertwined and entangled — as if by the hand of a basket maker — that they formed an impenetrable shade. The third branch stretched out horizontally above the roaring waters, into which its lower leaves dipped. The tree made an island of green in the midst of the surrounding ocean. Space was not lacking in the interior of this gigantic tree, for there were great gaps in the foliage, perfect glades, with air in abundance, and freshness everywhere. To see the innumerable branches rising to the clouds, parasitic lianas running from bough to bough, and attaching them together, while the sunlight glinted here and there among the leaves, one might have called it a complete forest instead of a solitary tree sheltering them all.

A myriad of the feathered tribes fled away into the topmost branches on the arrival of the fugitives, protesting this flagrant usurpation of their domicile with their outcries. These birds, who themselves had taken refuge in the solitary ombú, were there by the hundreds: blackbirds, starlings, isacas, jilgueros1, and especially the picaflors2 of most resplendent colours. When they flew away it seemed as though a gust of wind had stripped the tree of its flowers.

Such was the asylum offered to Glenarvan’s little band. Young Grant and the agile Wilson were scarcely perched on the tree before they had climbed to the upper branches and put their heads through the leafy dome to get a view of the vast horizon. The ocean made by the inundation surrounded them on all sides, and, far as the eye could reach, seemed to have no limits. Not a single tree was visible on the liquid plain; the ombú stood alone amid the rolling waters, and trembled in them. In the distance, drifting from south to north, carried along by the impetuous torrent, they saw trees torn up by the roots, twisted branches, roofs torn from destroyed ranchos, planks of sheds stolen by the deluge from estancias, carcasses of drowned animals, blood-stained skins, and on one shaking tree a whole family of jaguars, howling and clutching hold of their frail raft. Still farther away, a black spot — almost invisible already — caught Wilson’s eye. It was Thalcave and his faithful Thaouka.

“Thalcave, Thalcave!” shouted Robert, waving his arms at the courageous Patagonian.

“He will save himself, Mr. Robert,” said Wilson. “We must go down to His Honour.”

In a moment they had descended through three storeys of boughs, and landed safely on the top of the trunk, where they found Glenarvan, Paganel, the Major, Austin, and Mulrady, sitting either astride or in some position they found more comfortable. Wilson gave his report on their visit to the summit of the ombú, and all shared his opinion with respect to Thalcave. The only question was whether it was Thalcave who would save Thaouka, or Thaouka who would save Thalcave.

Their own situation was much more alarming than his. The tree would likely be able to resist the current, but the waters might rise higher and higher, until the topmost branches were covered, for the basin of this part of the plain made a deep reservoir. Glenarvan’s first concern, consequently, had been to make notches by which to track the progress of the flood. For the present it was stationary, having apparently reached its height. This was reassuring.

“And now what are we going to do?” said Glenarvan.

“Make our nest, parbleu!” said Paganel

“Make our nest?” asked Robert.

“Certainly, my boy, and live the life of birds, since we can’t that of fishes.”

“All very well, but who will fill our bills for us?” said Glenarvan.

“Me,” said the Major.

All eyes turned toward him immediately, and there he sat in a natural arm-chair formed of two elastic boughs, holding out his alforjas damp, but still intact.

“Oh, MacNabbs, that’s just like you,” said Glenarvan. “You keep your head, while everyone around you is losing theirs.”

“As soon as it was decided that we were not going to be drowned, I had no intention of dying of hunger.”

“I should have thought of it, too,” said Paganel, “but I am so distrait.”

“And what is in the alforjas?” asked Tom Austin.

“Food enough to last seven men for two days,” said MacNabbs.

“And I hope the flood will have gone down in twenty-four hours,” said Glenarvan.

“Or that we shall have found some other way of regaining terra firma,” added Paganel.

“Our first business then, is to have breakfast,” said Glenarvan.

“After drying ourselves, though,” said the Major.

“And where’s the fire?” asked Wilson.

“We must make it,” replied Paganel.

“Where?”

“On the top of the trunk, parbleu.”

“And what with?”

“With the dead wood we cut off the tree.”

“But how will you light it?” asked Glenarvan. “Our tinder looks like a wet sponge.”

“We can dispense with it,” replied Paganel. “We only need a little dry moss and a ray of sunshine, and the lens of my telescope, and you’ll see what a fire I’ll get to dry myself by. Who will go and cut wood in the forest?”

“I will,” said Robert.

And off he scampered like a young cat into the depths of the foliage, followed by his friend Wilson. Paganel set to work to find dry moss, and had soon gathered sufficient. He procured a ray of sunshine, which was easy for the sun was shining brightly, and focused with his lens, the moss was easily kindled. This he laid on a bed of damp leaves, at the trifurcation of the large branches, forming a natural hearth, from which there was little fear of the fire spreading.

Robert and Wilson had reappeared, each with an armful of dry wood, which they threw on the smouldering moss. In order to ensure a proper draught, Paganel stood over the hearth with his long legs straddled out in the Arab manner. Then stooping down and raising himself with a rapid motion, he made a violent current of air with his poncho, which made the wood take fire, and soon a bright flame roared in the improvised brazier.

They dried themselves, and hung their ponchos in the breeze

After drying themselves, each in his own fashion, and hanging their ponchos on the tree, where they were swung to and fro in the breeze, they ate breakfast, carefully rationing out the provisions, for the morrow had to be thought of. The immense basin might not empty as quickly as Glenarvan hoped, and the supply was very limited. The ombú produced no fruit. Fortunately, it would likely abound in fresh eggs, thanks to the numerous nests stowed away among the leaves, not to mention their feathered proprietors. These resources were by no means to be disdained.

The next business was to install themselves as comfortably as they could, in prospect of a long stay.

“As the kitchen and dining-room are on the ground floor,” said Paganel, “we must sleep on the first floor. The house is large, and as the rent is not dear, we must not cramp ourselves for room. I can see natural cradles up there, in which once safely tucked up we shall sleep as if we were in the best beds in the world. We have nothing to fear. Besides, we will watch, and we are numerous enough to repulse a fleet of Indians or wild animals.”

“We only need fire-arms,” said Austin.

“I have my revolvers,” said Glenarvan.

“And I have mine,” said Robert.

“But what good are they?” asked Tom Austin, “unless Monsieur Paganel can find some way of making powder.”

“We already have it,” said MacNabbs, exhibiting a powder magazine in a perfect condition.

“Where did you get that, Major?” asked Paganel.

“Thalcave. He thought we might need it, and gave it to me before he plunged into the water to save Thaouka.”

“Generous, brave Indian!” said Glenarvan.

“Yes,” said Tom Austin, “if all the Patagonians are cut from the same cloth, I must compliment Patagonia.”

“Do not forget the horse,” said Paganel. “She is part and parcel of the Patagonian, and I’m much mistaken if we don’t see them again, the one on the other’s back.”

“How far are we from the Atlantic?” asked the Major.

“About forty miles at the most,” said Paganel. “And now, friends, since everyone is free to choose their actions, I beg to take leave of you. I am going to choose an observatory for myself up there, and by the help of my telescope, let you know how things are going on in the world.”

The scientist was dismissed to his selected work, and hoisted himself up skilfully from bough to bough, until he disappeared into the thick foliage. His companions began to arrange the night quarters, and prepare their beds. This didn’t take long, as they had no blankets to spread, nor furniture to arrange and very soon they resumed their seats around the fire to talk.

They didn’t talk about their current situation, for which there was nothing more to do than to endure it patiently. They returned to the inexhaustible theme of Captain Grant. They would return on board the Duncan in three days, should the water subside. But Harry Grant and his two sailors, those unfortunate castaways, would not be with them. Indeed, it even seemed after this failure, and this useless journey across America, that all chance of finding them was gone forever. Where could they commence a fresh quest? What grief Lady Helena and Mary Grant would feel on hearing there was no further hope.

“My poor sister!” said Robert. “It’s all over, for us.”

For the first time Glenarvan could not find any comfort to give him. What could he say to the lad? Had they not followed with rigorous accuracy the indicated latitude of the document?

“And yet,” he said, “this 37th degree of latitude is not a mere figure. Whether it applies to the shipwreck or captivity of Harry Grant, it is no mere guess or supposition. We read it with our own eyes.”

“All very true, Your Honour,” said Tom Austin, “and yet our search has been unsuccessful.”

“It is both irritating and depressing,” said Glenarvan.

“Irritating, and depressing, I’ll grant you,” said the Major calmly, “but not hopeless. It is precisely because we have an incontestable figure provided for us, that we should follow it up to the end.”

“What do you mean?” asked Glenarvan. “What more can we do?”

“A very logical and simple thing, my dear Edward. Let’s turn east, when we’re aboard the Duncan, and follow the 37th parallel back to our starting point, if need be.”

“Do you suppose that I have not thought of that, Mr. MacNabbs?” said Glenarvan. “Yes, a hundred times. But what chance is there of success? Isn’t leaving the American continent going away from the very spot indicated by Harry Grant, from this very Patagonia so distinctly named in the document.”

“And would you recommence your search in the Pampas, when you have the certainty that the shipwreck of the Britannia occurred on neither the Pacific, nor Atlantic coast?”

Glenarvan was silent.

“And however small the chance of finding Harry Grant by following up the given parallel, ought we not to try?”

“I don’t say ‘no’,” said Glenarvan.

“And you, my friends,” said the Major to the sailors. “Do you share my opinion?”

“Entirely,” said Tom Austin, while Mulrady and Wilson nodded.

“Listen to me, friends,” said Glenarvan after a few moments of thought, “and listen well. Robert, this is a serious discussion. I will do my utmost to find Captain Grant; I am pledged to it, and will devote my whole life to the task if needs be. All Scotland would unite with me to save so devoted a son as he has been to her. I too think with you that we must follow the 37th parallel around the globe if necessary, however slight our chance of finding him, and I will do so. But that is not the question we have to settle. There is one much more important than that is. Should we give up our search on the American continent?”

No one made any reply. Each one seemed afraid to pronounce the word.

“Well?” asked Glenarvan, addressing himself especially to the Major.

“My dear Edward,” said MacNabbs, “it would be incurring too great a responsibility for me to reply hic et nunc3. It is a question which requires reflection. I must know first, through which countries the 37th parallel of southern latitude passes?”

“That’s Paganel’s business,” said Glenarvan.

“Let’s ask him, then,” said the Major.

But the scholar was nowhere to be seen, hidden by the thick foliage of the ombú. It was necessary to hail him.

“Paganel, Paganel!” shouted Glenarvan.

“Ici!” answered a voice from above.

“Where are you?”

“In my tower.”

“What are you doing there?”

“Examining the wide horizon.”

“Could you come down for a minute?”

“Do you need me?”

“Yes.”

“What for?”

“To know what countries are crossed by the 37th parallel.”

“Nothing is easier,” said Paganel. “I need not come down for that.”

“Very well, tell us now.”

“Listen, then. After leaving America the 37th parallel crosses the Atlantic Ocean.”

“And then?”

“It encounters the Tristan da Cunha Islands.”

“Yes.”

“It passes two degrees below the Cape of Good Hope.”

“And afterwards?”

“Runs across the Indian Ocean, and just touches Isle St. Pierre, in the Amsterdam group.”

“Go on.”

“It cuts Australia in the province of Victoria.”

“And then.”

“After leaving Australia it—”

This last sentence was not completed. Was the geographer hesitating, or didn’t he know what to say?

No. A terrible cry resounded from the top of the tree. Glenarvan and his friends turned pale and looked at each other. What fresh catastrophe had happened now? Had the unfortunate Paganel fallen?

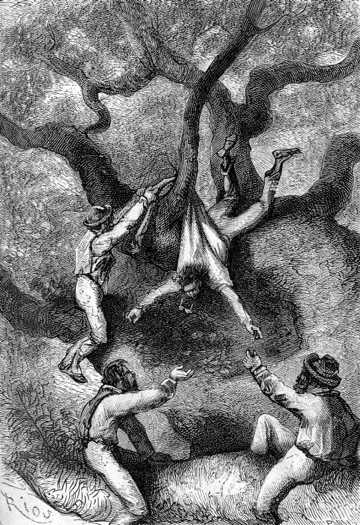

Paganel appeared, tumbling down from branch to branch

Already Wilson and Mulrady were rushing to his rescue when his long body appeared, tumbling down from branch to branch.

Was he alive? Was he dead? He made no attempt to catch himself. He was about to fall into the roaring waters when the Major stopped him.

“Much obliged, MacNabbs,” said Paganel.

“What is the matter with you?” said the Major. “What came over you? Another of your ‘distractions’?”

“Yes, yes,” said Paganel, in a voice almost inarticulate with emotion. “Yes, a distraction, but this was something phenomenal.”

“What was it?”

“We were wrong! We are wrong again! We are always wrong!”

“Explain yourself.”

“Glenarvan, Major, Robert, my friends!” cried Paganel. “All you that hear me, we are looking for Captain Grant where he is not to be found.”

“What do you mean?” exclaimed Glenarvan.

“Captain Grant is not now, nor has he ever been, lost in America!”

1. Goldfinches — DAS

2. Hummingbirds — DAS

3. Latin: here and now — DAS