The hunt was going well

Profound astonishment greeted these unexpected words. What could the geographer mean? Had he lost his mind? He spoke with such conviction, however, that all eyes turned toward Glenarvan, for Paganel’s statement was a direct answer to the question he had so recently posed to them. But Glenarvan confined himself to shaking his head at the scientist’s sudden assertion.

Paganel soon had better control over himself. “Yes!” he said with conviction. “Yes! We went astray in our research, and read into the document words that were never there!”

“Explain yourself, Paganel,” said the Major. “And more calmly, if you can.”

“It’s very simple, Major. As you were in error, I too was thrown into a false interpretation. Just a moment ago, at the top of this tree, answering your questions, and stopping on the word ‘Australia’, a lightning flash went through my brain and it came to me.”

“What?” exclaimed Glenarvan. “Do you claim that Harry Grant—”

“I claim,” said Paganel, “that the word ‘austral’ that occurs in the document is not a complete word, as we have thought so far, but just the root of the word Australie.”

“Well, that would be strange,” said the Major.

“Strange?” Glenarvan shrugged his shoulders. “It is simply impossible.”

“Impossible?” said Paganel. “That is a word we don’t allow in France.”

“How?” asked Glenarvan, in a tone of the most profound incredulity. “How do you dare to contend, with the document in your hand, that the shipwreck of the Britannia happened on the shores of Australia?”

“I am sure of it,” replied Paganel.

“Well, Paganel,” said Glenarvan, “that is a declaration which astonishes me a great deal, coming from the Secretary of the Geographical Society!”

“And why so?” said Paganel, poked in his vanity.

“Because, if you allow the word Australie! you must also allow the word Indiens, and Indians are never seen there.”

Paganel was not the least surprised at this rejoinder. Doubtless he expected it, for he began to smile, and said:

“My dear Glenarvan, do not hasten to triumph. I am going to ‘battre à plates coutures’1 as we Frenchmen say, and never was an Englishman more thoroughly defeated than you will be. It will be the revenge for Crécy and Agincourt.”

“I wish nothing better. Take your revenge, Paganel.”

“Listen, then. In the text of the document, there is neither mention of the Indians nor of Patagonia! The incomplete word ‘indi’ does not mean Indiens, but of course, indigenes, natives! Now, do you admit that there are ‘natives’ in Australia?”

“Bravo, Paganel!” said the Major.

“Well, do you agree to my interpretation, my dear Lord?”

“Yes,” replied Glenarvan, “if you will prove to me that the fragment of a word ‘gonie’, does not refer to the country of the Patagonians.”

“Certainly it does not. It has nothing to do with Patagonia,” said Paganel. “Read it any way you please except that.”

“How?”

“Cosmogonie, theogonie, agonie.”

“Agonie!” said the Major.

“I don’t care which,” said Paganel. “The word does not matter; I will not even try to find out its meaning. The main point is that ‘austral’ means Australie, and we must have gone blindly on a wrong track not to have discovered the explanation at the very beginning, it was so evident. If I had found the document myself, and my judgment had not been misled by your interpretation, I should never have read it differently.”

A burst of hurrahs, and congratulations, and compliments followed Paganel’s words. Austin and the sailors, the Major, and especially Robert were overjoyed at this new hope, and applauded him heartily. Even Glenarvan was almost prepared to give in.

“I only want to know one thing more, my dear Paganel,” he said, “and then I must bow to your perspicacity.”

“What is it?”

“How will you group the words together according to your new interpretation? How will the document read?”

“Easily enough answered. Here is the document.” Paganel took out the precious paper he had been studying so conscientiously for the last few days.

There was a profound silence, while the geographer collecting his thoughts, took his time to answer. His finger followed the broken lines on the document, while in a sure voice, and emphasizing certain words, he read:

“‘On June 7, 1862, the three-master Britannia of Glasgow sank after … ’ Let’s say, if you like, ‘two days, three days’ or ‘a long agony,’ it does not matter, it’s totally irrelevant, ‘on the shores of Australia. Heading to land, two sailors and Captain Grant will try to approach’ or ‘landed the continent where they will be’ or ‘are prisoners of cruel indigenes. They threw this document,’ etc., etc.

“Is that clear?”

“Clear enough,” replied Glenarvan, “if the word ‘continent’ can be applied to Australia, which is only an island!”

“Rest assured, my dear Glenarvan; the best geographers have agreed to call the island ‘the Australian Continent’.”

“Then all I have to say now, my friends, is away to Australia!” said Glenarvan. “And may Heaven help us!”

“To Australia!” echoed his companions, with one voice.

“Do you know, Paganel,” said Glenarvan, “that your being on board the Duncan is a providential event.”

“All right. Look on me as an envoy of Providence, and let us not talk about it again.”

Thus ended this conversation, which had such great consequences for their future. It completely changed the morale of the searchers. They had just seized the thread to lead them out of this labyrinth in which they had believed themselves forever lost. A new hope arose over the ruins of their collapsed plans. They could safely leave behind this American continent, and all their thoughts were already flying to Australia. They would not bring despair when they re-boarded the Duncan. Lady Helena, and Mary Grant would not have to mourn the irrevocable loss of Captain Grant! So they forgot the dangers of their situation to indulge in joy, and they had only one regret: that they were not able to leave immediately.

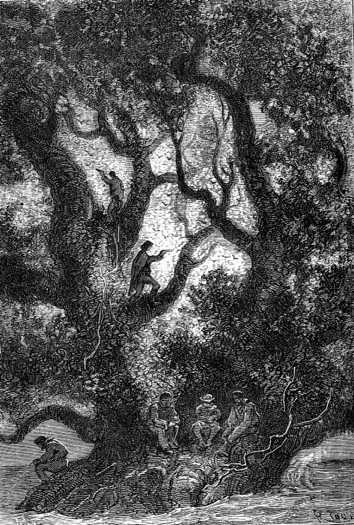

It was about four o’clock in the afternoon, and they determined to have supper at six. Paganel wished to prepare a splendid spread in honour of the occasion, but as their supplies were very scanty, he proposed to Robert that they should go and hunt in “the neighbouring forest.” Robert clapped his hands at the idea, so they took Thalcave’s powder magazine, cleaned and loaded the revolvers, and set off.

“Don’t go too far,” said the Major, solemnly, to the two hunters.

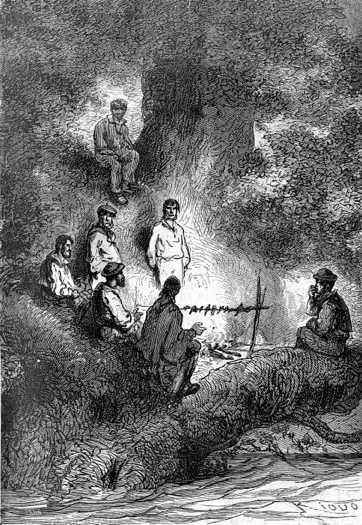

After their departure, Glenarvan and MacNabbs went down to examine the state of the water by looking at the notches they had made on the tree, while Wilson and Mulrady replenished the fire.

Glenarvan saw no sign of the flood abating, but it seemed to have reached its maximum height. But the violence with which the water still rushed northward proved that the equilibrium of the Argentinian rivers was not yet restored. Glenarvan did not expect the waters to start to recede as long as the current kept running so strong.

The hunt was going well

While Glenarvan and his cousin were making these observations, the report of firearms resounded frequently above their heads, accompanied by shouts of joy almost as loud. Robert’s soprano mixed with Paganel’s bass. No one could say who was the most childish. The hunt was going well, and wonders in culinary art might be expected. When Glenarvan returned to the brazier, he congratulated Wilson on an excellent idea, which he had skilfully carried out. The brave fellow had managed to catch, with only a pin and a piece of string, several dozen small fish, as delicate as smelts, called mojarras, which were all jumping about in a fold of his poncho, ready to be converted into an exquisite dish.

The hunters came down from the ombú peaks. Paganel was cautiously carrying some black swallows’ eggs, and a string of sparrows, which he meant to serve up later under the name ‘wimps’. Robert had skilfully brought down several pairs of jilgueros, small green and yellow birds, which are excellent to eat, and greatly in demand in the Montevideo market. Paganel, who knew fifty-one ways of preparing eggs, was obliged for this once to be content with simply hardening them on the hot embers. Never the less, the meal was as varied as it was delicate. The dried beef, hard eggs, grilled mojarras, sparrows, and roast jilgueros, made one of those gala feasts whose memory is imperishable.

The conversation was very cheerful. Many compliments were paid Paganel on his twofold talents as hunter and cook, which the scholar accepted with the modesty which characterizes true merit. Then he turned the conversation to the peculiarities of the ombú, under whose canopy they had found shelter, and whose depths he declared were immense.

“Robert and I,” he added, jestingly, “thought ourselves hunting in the open forest. I was afraid, for a minute, we should lose ourselves, for I could not find the road. The sun was sinking below the horizon; I sought vainly for footmarks; I began to feel the sharp pangs of hunger, and the gloomy depths of the forest resounded already with the roar of wild beasts. No, not that; there are no wild beasts here, I am sorry to say.”

“What!” exclaimed Glenarvan, “you are sorry there are no wild beasts?”

“Certainly, I am.”

“And yet we should have every reason to dread their ferocity.”

“Their ferocity is non-existent, scientifically speaking,” said the learned geographer.

“Now come, Paganel,” said the Major, “you’ll never make me admit the utility of wild beasts. What good are they?”

“Why, Major,” exclaimed Paganel, “for purposes of classification into orders, and families, and species, and sub-species.”

“A mighty advantage, certainly!” said MacNabbs, “I could dispense with all that. If I had been one of Noah’s companions at the time of the deluge, I should most assuredly have hindered the imprudent patriarch from putting in pairs of lions, and tigers, and panthers, and bears, and such animals, for they are as malevolent as they are useless.”

“You would have done that?” asked Paganel.

“Yes, I would.”

“Well, you would have done wrong in a zoological point of view.”

“But not in a humanitarian one,” said the Major.

“It is shocking! Why, for my part, on the contrary, I should have taken special care to preserve megatheriums and pterodactyls, and all the antediluvian species of which we are unfortunately deprived by his neglect.”

“And I say, that Noah did a very good thing when he abandoned them to their fate — that is, if they lived in his day.”

“And I say he did a very bad thing,” said Paganel, “and he has justly merited the malediction of scholars to the end of time!”

The rest of the party could not help laughing at hearing the two friends disputing over old Noah. Contrary to all his principles, the Major, who all his life had never disputed with anyone, was always sparring with Paganel. The geographer seemed to have a peculiarly exciting effect on him.

Glenarvan, as usual the peacemaker, intervened in the debate. “Whether the loss of ferocious animals is to be regretted or not, in a scientific point of view, there is no help for it now; we must be content to do without them. Paganel can hardly expect to meet with wild beasts in this aerial forest.”

“Why not?” asked the geographer.

“Wild beasts in a tree!” exclaimed Tom Austin.

“Yes, undoubtedly. The American tiger, the jaguar, takes refuge in the trees, when it is too much pressed by hunters. It is quite possible that one of these animals, surprised by the inundation, might have climbed up into this ombú, and be hiding now among its thick foliage.”

“You haven’t met any of them, at any rate, I suppose?” asked the Major.

“No,” replied Paganel, “though we hunted all through the wood. It is unfortunate, for it would have been a splendid chase. There is no more ferocious carnivore than the jaguar. He can twist the neck of a horse with a single stroke of his paw. Once he has tasted human flesh he scents it greedily. He likes to eat an Indian best, and next to him a negro, then a mulatto, and last of all a white man.”

“I am delighted to hear we come only forth,” said MacNabbs.

“That only proves you are bland,” said Paganel, with an air of disdain.

“I am delighted to be insipid.”

“Well, it is humiliating enough,” said the intractable Paganel. “The white man proclaims himself chief of the human race! It seems that this is not the opinion of the jaguars.”

“Be that as it may, my brave Paganel,” said Glenarvan, “seeing there are neither Indians, nor negroes, nor mulattoes among us, I am quite rejoiced at the absence of your beloved jaguars. Our situation is not so particularly agreeable.”

“What? Not agreeable!” exclaimed Paganel, jumping at the word as likely to give a new turn to the conversation. “Are you complaining of your lot, Glenarvan?”

“I should think so, indeed,” said Glenarvan. “Do you find these hard branches very luxurious?”

“I have never been more comfortable, even in my study. We live like the birds; we sing and fly about. I begin to believe men were intended to live in trees.”

“But we lack wings,” said the Major.

“We’ll make them some day.”

“In the meantime,” said Glenarvan, “with your leave, I prefer the gravel of a park, the floor of a house, or the deck of a ship, to this aerial dwelling.”

“We must take things as they come, Glenarvan,” said Paganel. “If good, so much the better; if bad, we’ll make do. Ah, I see you are wishing you had all the comforts of Malcolm Castle.”

“No, but—”

“I am quite certain Robert is perfectly happy,” interrupted Paganel, eager to insure he had at least one ally.

“Yes, Mr. Paganel!” exclaimed Robert, in a joyous tone.

“It’s his age,” said Glenarvan.

“And mine, too,” returned the geographer. “The fewer one’s comforts, the fewer one’s needs; and the fewer one’s needs, the greater one’s happiness.”

“Now, now,” said the Major, “here is Paganel running a tilt against riches and gilt ceilings.”

“No, MacNabbs,” said the scholar, “I’m not; but if you like, I’ll tell you a little Arabian story that comes into my mind, very apropos to our situation.”

“Oh, do, do!” said Robert.

“And what is your story to prove, Paganel?” asked the Major.

“Much of what all stories prove, my good companion.”

“Not much then,” said MacNabbs. “But go on, Scheherazade, and tell us one of those tales you tell so well.”

“Once upon a time …”

“Once upon a time,” said Paganel, “there was a son of the great Haroun-al-Raschid, who was unhappy, and went to consult an old Dervish. The old sage told him that happiness was a difficult thing to find in this world. ‘However,’ he added, ‘I know an infallible means of procuring your happiness.’ ‘What is it?’ asked the young Prince. ‘It is to put the shirt of a happy man on your shoulders.’ Whereupon the Prince embraced the old man, and set out at once to search for his talisman. He visited all the capital cities in the world. He tried on the shirts of kings, and emperors, and princes and nobles; but all in vain: he could not find a man among them that was happy. Then he put on the shirts of artists, and warriors, and merchants; but these were no better. By this time he had travelled a long way, without finding what he sought. At last he began to despair of success, and began sorrowfully to retrace his steps back to his father’s palace, when one day he saw in the country a brave ploughman, all happy and singing, who was pushing his plough. He thought, ‘Surely this man is happy, if there is such a thing as happiness on earth.’ Forthwith he accosted him, and said, ‘Are you happy?’ ‘Yes,’ was the reply. ‘There is nothing you desire?’ ‘Nothing.’ ‘You would not change your lot for that of a king?’ ‘Never!’ ‘Well, then, sell me your shirt.’ ‘My shirt? I don’t have one!’”

1. French: beat you flat — DAS