They returned to the Duncan

Glenarvan was not used to wasting time between the adoption of an idea, its execution. As soon as Paganel’s proposal was accepted, he immediately gave orders for the preparations for the journey to be completed as soon as possible. The departure date was set for December 22nd, in two days.

What results could this crossing of Australia produce? The presence of Harry Grant on the continent having become an indisputable fact, the consequences of this expedition could be great. Their chance of finding him had increased. No one flattered themselves with the idea that they would discover the captain exactly on the 37th parallel, which they intended strictly to follow, but they might come upon his track, and in any event, they were going to the actual site of the shipwreck. That was the main point.

Besides, if Ayrton consented to join them and act as their guide through the forests of Victoria Province, to lead them to the eastern coast, there was every chance of success. Glenarvan was sure of it. He was particularly anxious to secure the assistance of Harry Grant’s crewman. He asked his host if he would object to them taking Ayrton with them.

Paddy O’Moore consented, though he said he would regret the loss of his excellent worker.

“Well, will we follow you, Ayrton, on this expedition in search of the shipwrecked Britannia?” asked Glenarvan.

Ayrton did not reply immediately. He even showed signs of hesitation; but at last, after due reflection, said “Yes, My Lord, I will follow you, and if I do not lead you in the footsteps of Captain Grant, at least I will take you to the very spot where his ship wrecked.”

“Thank you, Ayrton,” said Glenarvan.

“Only one question, My Lord.”

“Yes?”

“Where will you meet the Duncan again?”

“In Melbourne, if we do not cross Australia from one shore to another. On the east coast, if our search extends that far.”

“And her Captain?”

“Her Captain will wait for my instructions in the port of Melbourne.”

“Well, My Lord,” said Ayrton, “you can count on me.”

“I am counting on it, Ayrton,” said Glenarvan.

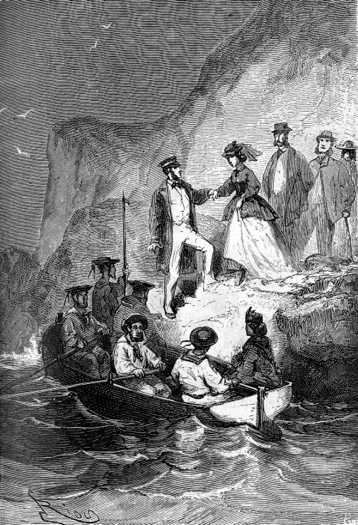

They returned to the Duncan

The quartermaster was warmly thanked by the Duncan’s passengers, and the children hugged him. Everyone was happy with his decision, except the Irishman, who was losing an intelligent and faithful worker. But Paddy understood the importance Glenarvan attached to the quartermaster’s presence, and resigned himself. Glenarvan commissioned him to procure the transportation needed for this trip across Australia, arranged a rendezvous with Ayrton, and their business concluded, the passengers returned onboard the Duncan.

It was a joyful return. Everything had changed. All hesitation disappeared. The brave searchers were no longer blindly following the 37th parallel. It could not be doubted that Harry Grant had found refuge on the continent, and everyone felt their hearts fill with the satisfaction of certainty after doubt.

In two months, if all went well, the Duncan would return Harry Grant to the shores of Scotland!

When John Mangles supported the proposal to cross Australia with the passengers, he supposed that this time he would accompany the expedition. So he conferred with Glenarvan. He put forward all sorts of arguments in his favour: his devotion to Lord and Lady Glenarvan, his usefulness as an organizer of the caravan, and his not being needed as Captain aboard the Duncan. He had a thousand more arguments marshalled, but he didn’t need them.

“I’ll only ask you one question, John,” said Glenarvan. “Do you have absolute confidence in your second?”

“Absolutely,” said John Mangles, “Tom Austin is a good sailor. He will take the ship to her destination, see that the repairs are skilfully executed, and bring her back on the appointed day. Tom is a slave to duty and discipline. Never would he take it on himself to alter or retard the execution of an order. Your Honour may count on him as on myself.”

“Very well then, John; you shall go with us.” Lord Glenarvan smiled. “It will be good that you will be there when we find Mary Grant’s father again.”

“Oh! Your Honour,” murmured John. That was all he could say. He paled for a moment, and seized the hand extended to him by Lord Glenarvan.

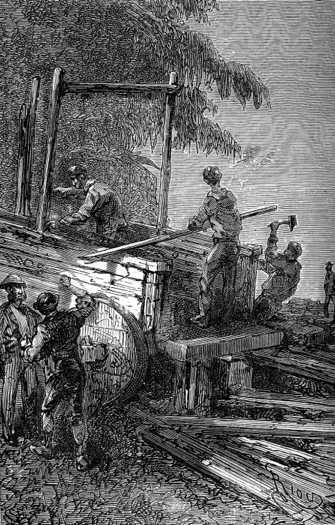

Next day, John Mangles, accompanied by the ship’s carpenter and sailors laden with provisions, returned to Paddy O’Moore’s farm to consult with the Irishman about the best method of transport.

The whole family was waiting for him, ready to work under his orders. Ayrton was there, as well, and gave the benefit of his experience.

He and Paddy agreed on the main point: that the journey should be made in an oxcart for the ladies, and that the gentlemen should ride on horseback. Paddy could provide both the animals, and vehicle.

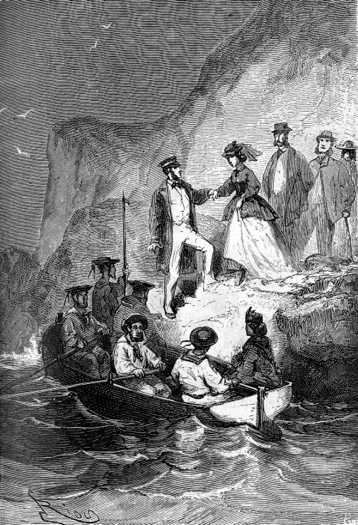

The preparation of the wagon

The vehicle was a wagon twenty feet long, covered over by a tarpaulin, and resting on four large wheels without spokes, or rims, or iron tires — simple wooden disks, in other words. The front and rear wheelsets were widely separated, and connected to the wagon by a rudimentary mechanism which did not allow the vehicle to turn sharply. A thirty-five foot pole extended out in front, to which six paired oxen were to be yoked. These animals, thus arranged, drew from the head and neck by the combination of a yoke fastened on their nape and a collar fixed to the yoke by an iron peg. It required great skill to drive this narrow machine, subject to long oscillations, and quick to veer aside, and to guide this team by means of a goad. The role of driver was assigned to Ayrton, for he had served his apprenticeship on the Irishman’s farm, and Paddy vouched for his competence.

There were no springs in the wagon, so it was not likely to be very comfortable, but it was the best option available. If the rough construction could not be altered, John Mangles resolved that the interior should be made as cozy as possible. First, it was divided into two compartments by a means of a plank partition. The back one was intended for the provisions and luggage, and Mr. Olbinett’s portable kitchen. The front was set aside for the ladies, and under the carpenter’s hands, was to be converted into a comfortable room, covered with a thick carpet, and fitted up with a wash-table and two berths reserved for Lady Glenarvan and Mary Grant. Thick leather curtains could shut in this compartment if necessary, and protect the occupants from the chilliness of the nights. In a pinch, such as during heavy storms, the men might find refuge there, but a tent was to be their usual shelter when the caravan camped for the night. John Mangles strove to furnish the small space with everything that the two ladies could possibly require. He succeeded so well, that neither Lady Helena nor Mary had cause to regret trading this rolling room for their comfortable cabins on board the Duncan.

Preparations for the rest of the party were simpler. Seven sturdy horses were provided for Lord Glenarvan, Paganel, Robert Grant, MacNabbs, John Mangles, and the two sailors, Wilson and Mulrady, who were to accompany their master in this new expedition. Ayrton had his natural place in the front of the wagon, and Mr. Olbinett, who was not inclined to riding, made room for himself among the baggage.

The horses and oxen were set to grazing in the Irishman’s meadows, ready to fetch when the time came to leave.

After all arrangements were made, and the carpenter set to work, John Mangles escorted the Irishman and his family back to the yacht, for Paddy wished to return the visit of Lord Glenarvan. Ayrton had thought it fit to come, as well, and about four o’clock the party came over the side of the Duncan.

They were received with open arms. Glenarvan offered them dinner on board, in return for their Australian hospitality. His offer was willingly accepted. Paddy was quite amazed at the splendour of the saloon: the furnishing of the cabins, the hangings, the tapestries, all the fittings of maple and rosewood excited his admiration. Ayrton, on the other hand, gave only moderate approval to these costly superfluities.

When he examined the yacht from a more marine point of view, the quartermaster of the Britannia was more impressed. He visited the bottom of the hold; he went down to the engine room, and inspected the machinery; he inquired as to its power, and its coal consumption; he explored the coal bunkers, the galley, and the supply of powder; he was particularly interested in the armoury, and the cannon mounted on the forecastle. Glenarvan saw that he was dealing with a man who knew his ships. Finally, Ayrton completed his tour by inspecting the masts and the rigging.

“You have a beautiful ship, My Lord,” he said.

“One of the best,” said Glenarvan.

“And what is her tonnage?”

“She displaces 210 tons.”

“If I’m not mistaken,” said Ayrton, “I’d say she can easily do fifteen knots, at full steam.”

“Say seventeen,” put in John Mangles, “and you’d be right.”

“Seventeen!” exclaimed the quartermaster. “Why, not a man-of-war — not the best among them, I mean — could catch her!”

“Not one,” said John Mangles. “The Duncan was built as a racing yacht, and would never let herself be beaten.”

“Even sailing?” asked Ayrton.

“Even sailing.”

“Well, My Lord, and you too, Captain,” said Ayrton, “allow a sailor who knows what a ship is worth, to compliment you on yours.”

“You are welcome to join her company, then, Ayrton,” said Glenarvan. “The decision is yours.”

“I will think on it, My Lord,” was all Ayrton said.

Just then Mr. Olbinett came to announce that dinner was served. Lord Glenarvan and his guests made their way to the quarterdeck.

“That Ayrton is an intelligent man,” said Paganel to the Major.

“Too intelligent!” muttered MacNabbs, who, without any apparent reason, had taken a great dislike to the face and manners of the quartermaster.

During the dinner, Ayrton gave some interesting details about the Australian continent, which he knew well. He asked how many sailors were going to accompany the expedition. When he learned that only two of them, Mulrady and Wilson, were to go with them, he seemed surprised. He advised Glenarvan to take all his best men, and even insisted upon it. An insistence which, by the way, ought to have heightened the Major’s suspicion.

“But, our journey is not dangerous, is it?” asked Glenarvan.

“Not at all,” said Ayrton, quickly.

“Well, then, we’ll leave all the men we can on board. Hands will be needed to sail the Duncan, and to help in the repairs. Above all, it is important that she should meet us at our rendezvous, wherever it may be. So, we won’t reduce her crew.”

Ayrton seemed to understand Lord Glenarvan’s point, and said no more on the matter.

When evening came, Scottish and Irish separated. Ayrton and Paddy O’Moore’s family returned home. The horses and wagon were to be ready the next day. Departure was set for eight o’clock in the morning.

Lady Helena and Mary Grant made their last preparations. They were quickly done. Certainly more quickly than the meticulous preparations of Jacques Paganel. The scientist spent part of the night in disassembling, cleaning, polishing, and then reassembling the lenses of his telescope. So he was still sleeping when the Major woke him at dawn with a resounding bellow.

The luggage had already been transported to the farm by John Mangles. A boat was waiting to take the passengers, who soon took their places. The young captain gave his final orders to Tom Austin. He impressed upon him that he was to wait at Melbourne for Lord Glenarvan’s commands, and to obey them scrupulously, whatever they might be.

The old sailor told John he might rely on him, and, in the name of the men, begged to offer his Honour their best wishes for the success of this new expedition. A round of thunderous hurrahs burst from the crew.

In ten minutes the boat reached shore, and a quarter of an hour later the travellers arrived at the Irishman’s farm.

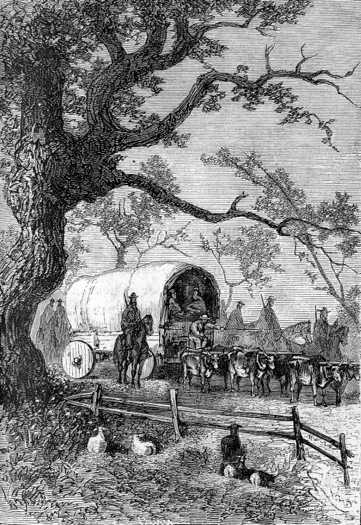

All was ready. Lady Helena was delighted with the arrangements. The huge wagon, with its primitive wheels and massive planks, pleased her particularly. The six oxen yoked in pairs had a patriarchal air about them which quite took her fancy.

“Parbleu!” said Paganel. “This is an admirable vehicle. It beats all the coaches of the world. A house that moves: goes or stops wherever you please. What else can one wish for?”

“Monsieur Paganel,” said Lady Helena, “I hope I shall have the pleasure of seeing you in my salon.”

“Assuredly, Madame, I should count it an honour. Have you fixed a day?”

“I shall be at home every day to my friends,” said Lady Helena; “and you are—”

“The most devoted of all, Madame,” interrupted Paganel, gallantly.

This exchange of courtesies was interrupted by the arrival of the seven horses, all saddled by one of Paddy’s sons. Lord Glenarvan paid the sum agreed for his various purchases, adding his cordial thanks, which the worthy Irishman valued at least as much as the guineas.

The signal to start was given

The signal was given to start, and Lady Helena and Mary took their places in the reserved compartment. Ayrton seated himself in front, and Olbinett scrambled in among the luggage. Glenarvan, the Major, Paganel, Robert, John Mangles, and the two sailors, well armed with rifles and revolvers, mounted their horses. A “God help you!” was shouted by Paddy O’Moore, and echoed in chorus by his family. Ayrton gave a peculiar cry, and his team set off. The wagon shook, the planks crackled, the axles creaked in the hubs of the wheels. The searchers soon disappeared around the bend in the road leading eastward from the hospitable farm of the honest Irishman.