Both horses and riders suffered the incessant bites of these tormenting diptera

It was December 23rd, 1864. December is a dull, damp, dreary month in the northern hemisphere, but on the Australian continent it might be called June. Astronomically, summer was already two days old, for on the 21st the sun had reached the Tropic of Capricorn, and its presence above the horizon was already diminishing by a few minutes each day. So it was in the hottest season of the year and under the rays of an almost tropical sun that Lord Glenarvan started on his new expedition.

All English possessions in this part of the Pacific Ocean are called Australasia. This includes New Holland, Tasmania, New Zealand, and some nearby islands. The Australian continent is divided into vast colonies of unequal wealth. Anyone who glances at modern maps drawn up by Messrs Petermann or Preschœll is at first struck with the rectangularity of these divisions. The English have drawn straight lines which separate these great provinces, without consideration of mountain slopes or river courses, or the variations in climate or differences in race. The colonies are placed rectangularly, like pieces of inlay. In this arrangement of straight lines and right angles one sees the hand of the geometer rather than the geographer. Only the coasts, with their varied windings, fjords, bays, capes, and estuaries, protest in the name of Nature with their charming irregularity.

This chess-board regularity justly inspired Jacques Paganel’s ire. If Australia had been French, the French geographers most certainly would not have carried a passion for the square and ruler to such lengths.

There are presently six colonies on the Big Island of Oceania: New South Wales, the capital of which is Sydney; Queensland, capital: Brisbane; Victoria, capital: Melbourne; South Australia, capital: Adelaide; Western Australia, capital: Perth; and Northern Australia, still without a capital1. The coasts alone are populated by settlers. Hardly anyone had ventured more than two hundred miles inland, even from the major cities. The interior of the continent, an area equal to two-thirds of Europe, was almost entirely unknown.

Fortunately the 37th parallel did not cross these immense, lonely, inaccessible lands, which have already cost many victims to science. Glenarvan could never have faced them. He was dealing with only the southern part of Australia, which consisted of a narrow stretch of the province of South Australia, the full width of the province of Victoria, and finally the tip of the inverted triangle formed by New South Wales.

It is scarcely sixty-two miles2 from Cape Bernouilli to the Victoria border. It was not more than two days’ march, and Ayrton planned to sleep the next evening at Apsley, the westernmost town in the province of Victoria.

The beginnings of a trip are always marked by the enthusiasm of riders and horses. This is well enough in the riders, but it seemed appropriate to moderate the pace of the horses. Whoever wants to go far must spare his horse. It was therefore decided that they should try to average no more than twenty-five to thirty miles each day.

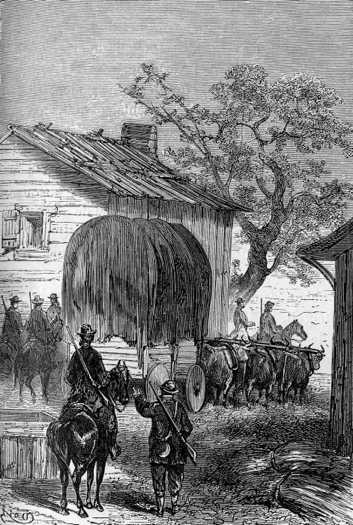

Besides, the pace of the horses was regulated by the slower pace of the oxen, truly mechanical engines which lose in time what they gain in power. The wagon, with its passengers and provisions, was the nucleus of the caravan, the travelling fortress. The horsemen might beat the flanks of their advance, but never ventured far away from it.

As no special marching order had been adopted; everyone was at liberty to follow his inclinations, within limits. The hunters could scour the plain, amiable folks could talk to the fair occupants of the wagon, and philosophers could philosophize. Paganel, who was all three combined, had to be, and was, everywhere at once.

The march across South Australia presented nothing of any particular interest. A succession of low hills rich in dust, a long expanse of wastelands which together constitute what Australians call “bush”: some meadows covered by tufts of a salty shrub with angular leaves which the sheep are very fond of, succeeded each other for many miles. Here and there they could see some “pig’s faces,” a species of sheep peculiar to New Holland that had a head like a pig, grazing between the poles of the telegraph line recently established to Adelaide on the coast.

These plains bore a singular resemblance to the extended monotony of the Argentinian Pampas. There was the same grassy flat soil, the same sharply-defined horizon against the sky. MacNabbs declared they had never changed countries, but Paganel assured him that the country would change soon. On his guarantee, they expected wonderful things.

Both horses and riders suffered the incessant bites of these tormenting diptera

About three o’clock the wagon crossed a large, treeless space known as “Mosquito Plains.” The scientist had the satisfaction of proving for himself that the name had been worthily bestowed. Both horses and riders suffered severely from the incessant bites of these tormenting diptera. It was impossible to escape them, but there was a salve made with ammonia carried in the wagon’s portable pharmacy which eased their bites. Paganel could not help but damn those bitter mosquitoes that larded his long person with their annoying stings.

Toward evening, a few quickset hedges of acacias enlivened the plain, and thickets of white gum trees were scattered here and there. A little further on they came to a freshly dug ditch, and then to trees of European origin: olives, lemon-trees, and holm oaks, and finally to well-kept fences. About eight o’clock, the oxen, urged on by Ayrton’s goad, arrived at Red Gum Station.

The word “station” is applied to large cattle-breeding establishments — the principle wealth of Australia — the owners of which are called “squatters,” people who sit on the ground.3 Certainly this is the most natural position a colonist would take when fatigued from a long journey through a vast unknown country.

Red Gum Station

Red Gum Station was a small establishment, but Glenarvan found the most sincere hospitality there. The table is invariably served for the traveller under the roof of these lonely dwellings, and in every Australian colonist one is sure to find an obliging host.

Ayrton harnessed his oxen the next morning at daybreak. He wanted to reach the Victoria territory that evening. The ground gradually became more uneven. A succession of small hills undulated as far as the eye could see, all sprinkled with scarlet sand. One might have imagined an immense red flag had been thrown over the plain, whose folds were swelled by a breath of wind. Some “mallees” with multiple straight, smooth trunks growing from a single root, spread their dark green branches and foliage over lush meadows swarming with merry bands of jerboa. Further on were vast fields of scrub and young gum trees, the fields became fewer, the shrubs became trees, and presented the first specimen of an Australian forest.

As they approached the frontiers of Victoria, the country’s appearance changed significantly. The travellers felt they were treading on new ground. Their imperturbable path was always a straight line without any obstacle, lake or mountain, obliging them to change it into a curved or broken line. They invariably put into practice the first theorem of geometry, and followed, without turning aside, the shortest path from one point to another. They experienced neither fatigue, nor difficulty. Their march conformed to the slow pace of the oxen, and if these quiet animals did not go quickly, at least they went without stopping.

On the evening of December 23rd, after a sixty-mile trek in two days, the caravan reached the parish of Apsley, the first town in the province of Victoria, situated on the one hundred and forty-first degree of longitude, in the district of Wimmera.

The wagon was stored by Ayrton at an inn which, for lack of a better name, was called the Crown Hotel. Their supper, which consisting solely of multiple varieties of mutton, steamed on the table.

They ate a lot, but talked more. Everyone questioned the geographer, eager to learn about the peculiarities of the Australian continent. The amiable geographer needed no pressing, and described this Victorian province, which was named Australia Felix.

“Wrongly named!” he said. “It would have been better to call it ‘Rich Australia,’ for it is true of countries, as individuals, that riches do not make happiness. Australia, thanks to its gold mines, has been abandoned to wild and devastating adventurers. You will see this when we cross the gold fields.”

“Is not the colony of Victoria of recent origin?” asked Lady Glenarvan.

“Yes, Madame, she is only thirty years old. It was on the 6th of June, 1835, on a Tuesday—”

“At a quarter past seven in the evening,” put in the Major, who liked to quibble with Paganel about his precise dates.

“No,” said the geographer, seriously. “It was at seven minutes past ten that Batman and Fawkner first began a settlement at Port Phillip, the bay on which the great city of Melbourne now lies. For fifteen years the colony was part of New South Wales, and recognized Sydney as its capital; but in 1851, she was declared independent, and took the name of Victoria.”

“And has she prospered since?” asked Glenarvan.

“Judge for yourself, my noble friend,” said Paganel. “Here are the numbers given by the latest census; and whatever MacNabbs thinks, I know nothing more eloquent than statistics.”

“Go on,” said the Major.

“Well, then, in 1836, the colony of Port Phillip had 244 inhabitants. Today the province of Victoria numbers 550,000. Seven million vines produce 121,000 gallons of wine, annually. There are 103,000 horses galloping over its plains, and 675,272 horned cattle graze in her immense pastures.”

“Does she not also have a certain number of pigs?” asked MacNabbs.

“Yes, Major. 79,625, if you please.”

“And how many sheep, Paganel?”

“7,115,943, MacNabbs.”

“Including the one we are eating at this moment?”

“No, without counting that, since it is three quarters devoured.”

“Bravo, Monsieur Paganel,” exclaimed Lady Helena, laughing heartily. “It must be admitted that you are well informed in geographical questions, and my cousin MacNabbs will not trip you up.”

“But it’s my job, Madame, to know this sort of thing, and to teach it when necessary. You can believe me when I tell you that this strange country holds many marvels.”

“None so far, however,” said MacNabbs, still enjoying teasing the geographer.

“Just wait, impatient Major,” said Paganel. “You have hardly put your foot on the frontier, and you are already complaining! Well, I say, and say again, and will always maintain, that this is the most curious country on the earth. Its formation, its nature, its products, and its climate, past, present and future, have amazed, are now amazing, and will amaze, all the scientists of the world. Think, my friends of a continent, the margin of which, instead of the centre, rose out of the waves like a gigantic ring; perhaps this ring encloses in its centre a partially evaporated sea, whose rivers are drying up daily; where moisture does not exist either in the air or in the soil; where the trees lose their bark every year, instead of their leaves; where the leaves present their profile to the sun instead of their face, and do not give shade; where the wood is often incombustible, where good-sized stones are dissolved by the rain; where the forests are low and the grasses high; where the animals are strange; where quadrupeds have beaks, like the echidna and platypus, and naturalists have been obliged to create a special order for them, called monotremes; where the kangaroos leap on unequal legs, and sheep have pigs’ heads; where foxes fly about from tree to tree; where the swans are black; where rats make nests; where the bower-bird opens his salon to receive visits from his feathered friends; where the birds astonish the imagination by the variety of their songs and their aptitudes; where one bird serves for a clock, and another makes a sound like a postilion cracking a whip, and a third imitates a knife-grinder, and a fourth the motion of a pendulum; where one laughs when the sun rises, and another cries when the sun sets! Oh, strange illogical country, land of paradoxes and anomalies, if ever there was one on earth — the learned botanist Grimard was right when he said, ‘So this is Australia, a kind of parody of universal laws, or rather a challenge, thrown in the face of the rest of the world.’4”

Paganel’s tirade, launched at full speed, seemed unlikely to stop. The eloquent secretary of the Geographical Society was no longer self possessed. He went on and on, gesticulating furiously, and waving his fork to the imminent danger of his neighbours at the table. But at last his voice was drowned in a thunder of applause, and he managed to stop.

Certainly, after this enumeration of Australian peculiarities, there was no thought of asking Paganel to go on. But the Major could not help but to say “And is that all, Paganel?” in his calmest tones.

“Well no! That’s not all,” said the scientist, and seemed ready to relaunch himself.

“What?” asked Lady Helena. “There are more wonders still in Australia?”

“Yes, Madame: its climate. It is even stranger than its productions.”

“For example?” they all asked.

“I am speaking of the hygienic qualities of the Australian continent, so rich in oxygen and low in nitrogen. It has no humid winds, since the trade winds blow parallel to its coasts, and most diseases are unknown here, from typhus to measles, and chronic afflictions.”

“That is no small advantage,” said Glenarvan.

“No doubt, but I am not referring to that,” said Paganel. “There is one quality to the climate here that is … improbable.”

“And what is that?” asked John Mangles

“You will never believe me.”

“Believe what,” asked his audience, determined to hear his response.

“Well, it’s…”

“It’s what?”

“It’s moralistic!”

“Moralistic?”

“Yes,” said the scientist with conviction. “Yes, moralistic! Metals do not oxidize in the air, here, nor men. Here, the pure, dry atmosphere whitens everything rapidly, both linen and souls. The virtues of this climate were known in England, when it was decided to send people here to reform.”

“What? This influence is really felt?” asked Lady Helena.

“Yes, Madame, on animals and men.”

“Are you joking, Monsieur Paganel?”

“I am not joking. Horses and cattle are remarkably docile. You will see it.”

“It is not possible!”

“But it is a fact. And the convicts transported into this invigorating and salubrious air regenerate themselves in a few years. Philanthropists know this. In Australia, all natures grow better.”

“But what of you then, Monsieur Paganel? You who are so good already,” asked Lady Helena. “What will become of you in this privileged land?”

“Excellent, Madame,” said Paganel. “Simply excellent.”

1. Darwin would be made the Northern Territory’s capital in 1870 — DAS

2. 25 leagues. (100 kilometres — DAS)

3. From the English verb “to squat”, to sit down.

4. Grimard, Edouard. The Plant, A Simplified Botany. Paris: J. Hetzel, 1864