The rare and illusive “jabiru”

They started at dawn the next day, December 24th. The weather was hot, but tolerable, and the road was level and favourable to the pace of the horses. They passed through a land of sparse scrub. In the evening, after a good day’s travel, they camped on the banks of White Lake, the waters of which were brackish and undrinkable.

Jacques Paganel was forced to agree that this lake was no more white than the Black Sea was black, the Red Sea red, the Yellow River yellow, or the Blue Mountains blue. He argued and disputed the point for the sake of geographer’s honour, but his arguments did not prevail.

Mr. Olbinett prepared the evening meal with his accustomed punctuality; then the travellers, some in the wagon, the others in the tent, soon fell asleep, in spite of the melancholy howls of the “dingoes,” the jackals of Australia.

A magnificent plain, thickly covered with chrysanthemums, extended beyond White Lake. Glenarvan and his friends would gladly have explored its beauties when they awoke next morning, but they had to be on their way. The land was flat, except for some distant low hills. A vast meadow stretched out as far as the eye could see, enamelled with flowers, in all the profusion of spring. The blue flowers of slender-leaved flax, intermingled with the bright red hues from a variety of acanthus peculiar to Australia. Many types of eucalyptus brightened this greenery, and salt impregnated land disappeared under the anserina, orache, and chard, some glaucous, others reddish, of the invasive salsoloideae family. These plants are useful to industry, because an excellent soda can be produced by washing their ashes, after incineration. Paganel, who became a botanist when he found himself among flowers, called these various plants by their names, and, with his mania for enumerating everything, did not fail to state that there were upward of 4,200 species of plants, divided into 120 families in the Australian flora.

Later in the day, after a quick march of about ten miles, the wagon wound its way through groves of tall acacias, mimosas, and white gum trees, whose inflorescence is so variable. The vegetable kingdom in this country of “spring plains”1 is not ungrateful to the day star, and returned the sunlight given it with perfumes and colours.

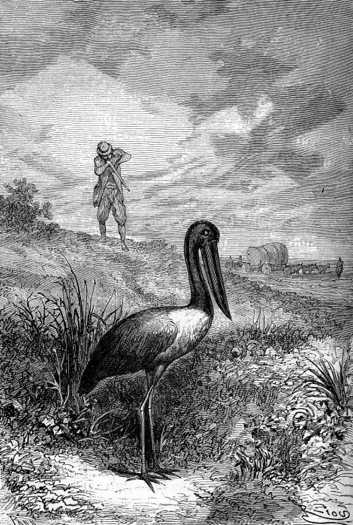

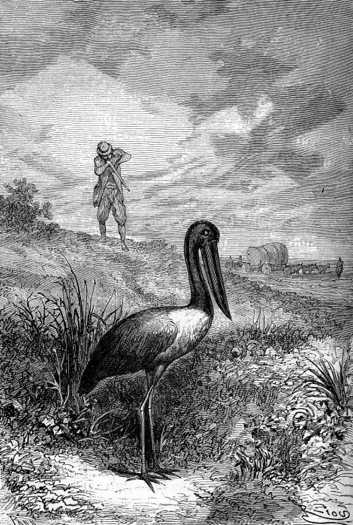

The rare and illusive “jabiru”

The animal kingdom was more stingy with its products. A few cassowaries were bounding over the plain, but it was impossible to get near them. The Major was skilful enough to hit one very rare and illusive animal with a bullet in the flank. This was the “jabiru,” the giant stork of the English colonies. This bird was five feet tall, and its black, broad, conical beak with an extremely sharp tip was eighteen inches long. The violet and purple hues of its head contrasted vividly with the glossy green of its neck, the dazzling whiteness of its shoulders, and the bright red of its long legs. Nature seemed to have used up all the primary colours of her palette on this bird.

The bird was greatly admired, and the Major would have had the honours of the day, had not Robert come across an animal a few miles further on, and bravely killed it. It was a shapeless creature, half hedgehog, half anteater, a sort of roughed-out animal belonging to the first ages of creation. An extendible tongue, long and sticky, hung out of its mouth in search of ants, which formed its principal food.

“It’s an echidna!” said Paganel, giving the monotreme its proper name. “Have you ever seen such an animal?”

“It’s horrible,” said Glenarvan.

“Horrible, but curious,” said Paganel. “And, what’s more, peculiar to Australia. One might search for it in vain in any other part of the world.”

Naturally, Paganel wanted to take the ugly echidna and stow it in the luggage compartment. But Mr. Olbinett protested the idea so indignantly that the scholar gave up the idea of keeping this monotreme specimen.

They passed 142°2 of longitude that day. So far, few colonists or squatters had come in sight. The country seemed deserted. There was not even the shadow of an Aborigine, because the wild tribes wander further north, through the vast solitudes watered by the tributaries of the Darling and Murray.

But a curious sight interested Glenarvan’s troop, for they chanced upon one of those immense droves of cattle which bold speculators bring down from the mountains in the east to the provinces of Victoria and South Australia.

About four o’clock in the afternoon, John Mangles reported an enormous column of dust on the horizon, about three miles off. What could be the cause of this phenomenon? Paganel’s lively imagination tried to concoct some natural explanation. Perhaps it was caused by a meteor, or— Ayrton summarily cut off his conjectures. It was the dust from a moving herd of cattle.

The quartermaster was not mistaken. The thick cloud approached. A whole concert of bleating, neighing, and bellowing escaped from it. Human voices, in the form of shouts, whistles, and complaints mingled with this pastoral symphony.

A man came out of the noisy cloud. He was the chief conductor of this four-footed army. Glenarvan advanced toward him, and friendly relations were quickly established. The leader, or to give him his proper designation, the “stockeeper,” was part owner of the herd. His name was Sam Machell, and he was on his way from the eastern provinces to Portland Bay.

The flock numbered 12,075 head: one thousand oxen, eleven thousand sheep, and seventy-five horses. All these had been bought in the plains of the Blue Mountains in a poor, lean condition, and were going to be fattened up on the rich pasture lands of South Australia, and resold at a large profit. Sam Machell expected to make two pounds on each ox, and a half-pound on every sheep, which would net him a profit of fifty thousand francs.3 This was a lot of money, but a great deal of patience and energy were required to conduct such a restive, stubborn herd to their destination, and many hardships had to be endured. The profit was well earned.

Sam Machell told his story in a few words while the flock continued their march among the groves of mimosas. Lady Helena, Mary, and the dismounted horsemen seated themselves under the shade of a wide-spreading gum tree, and listened to his recital.

It was seven months since Sam Machell had started. He was moving about ten miles a day, and his endless journey would last another three months. Twenty dogs and thirty men, including five blacks who were very skilled in tracking any stray animals, assisted him in this laborious task. Six wagons followed the army. The drivers, armed with stockwhips — a nine foot lash attached to an eighteen inch handle — circulated between the ranks, reestablishing order wherever it was disturbed, while the dogs, the light cavalry of the regiment, preserved discipline in the flanks.

The travellers admired the discipline maintained in the herd. The different breeds were kept apart, for sheep and oxen get along rather badly. The oxen would never have grazed where the sheep had passed along, and consequently they had to go first, divided into two battalions. Five regiments of sheep commanded by twenty drivers followed, and the herd of horses brought up the rear.

Sam Machell pointed out to his listeners that the army guides were neither men nor dogs, but oxen: intelligent “leaders” whose superiority was recognized by their peers. They advanced in the first rank with perfect gravity, choosing the best road by instinct, and fully convinced of their right to be treated with respect. They were well looked after, for the herd obeyed them without question. If it was convenient for them to stop, it was necessary to yield to their pleasure, for not a single animal would move a step until these leaders gave the signal to set off.

Some details added by the stockeeper completed the history of this expedition, worthy of being written, if not commanded, by Xenophon himself. As long as the army marched over the plains, it was well enough, there was little difficulty or fatigue. The animals fed as they went along, and slaked their thirst at the numerous creeks that watered the plains, sleeping at night, travelling during the day, and gathered obediently to the dogs’ voices. But in the great forests of the continent, through the thickets of eucalyptus and mimosas, the difficulties grew. Platoons, battalions, and regiments mingled or scattered, and it took considerable time to collect them again. Should a leader unfortunately go astray, he had to be found at all cost, on pain of a general mutiny, and the blacks would sometimes take several days to find him again. During heavy rains the lazy beasts refused to stir, and when violent storms came a disorderly panic could seize these animals, driving them mad with terror.

By dint of energy and activity, the stockeeper triumphed over these ever increasing difficulties. He kept steadily on. Mile after mile of plains, woods, and mountains lay behind him. In addition to all his other qualities, there was one higher than all others that he needed. This was patience, unswerving patience, patience that could not only wait for hours or days, but for weeks. This was required for river crossings. There, the stockeeper would be constrained in front of a stream that might be easily forded. There was nothing stopping him but the obstinacy of the herd. The oxen would drink the water and turn back. The sheep fled in all directions, rather than face the liquid element. The stockeeper hoped that when night came he might manage them better, but they still refused to go forward. The rams were thrown by force, but the sheep would not follow. They tried thirst, by depriving the flock of water for several days, but when they were brought to the river again, they simply quenched their thirst, and still declined to enter the water. The lambs were carried over, hoping the mothers would be drawn after them, by their bleating. But the lambs might bleat as pitifully as they liked, the mothers never stirred. Sometimes it lasted a whole month, and the stockeeper didn’t know what to do with his bleating, bellowing, neighing army. Then, one fine day, without rhyme or reason, by some whim, a detachment crossed the river. The only difficulty now was to keep the whole herd from rushing helter-skelter after them. Confusion set in among the ranks, and many animals were drowned in the passage.

Such were the details given by Sam Machell. During his story, a large proportion of the herd had filed past in good order. It was time for him to return to his place at the head of his army, to lead them away to good pastures. He took his leave of Lord Glenarvan, mounted an excellent native horse, which one of his men held waiting for him, and after shaking hands cordially with everyone, took his departure. Moments later, he had disappeared into the swirl of dust.

The wagon resumed its interrupted journey in the opposite direction, and did not stop again until they halted for the night at the foot of Mount Talbot.

Paganel made the judicious observation that it was December 25th, the Christmas Day celebrated by English families. The steward had not forgotten it and a succulent supper, served under the tent, earned him the sincere compliments of the guests. Mr. Olbinett had quite outdone himself. He produced from his stores an array of European dishes that are seldom seen in the Australian wilderness. Reindeer ham, slices of salted beef, smoked salmon, barley and oatmeal cakes, tea with discretion, whisky in abundance, and a few bottles of port made up this astonishing meal. The little party might have thought themselves in the grand dining hall of Malcolm Castle, in the heart of the Highlands of Scotland.

Nothing was missing from this feast, from the ginger soup to the mince pies for dessert. Paganel thought to make an addition with the fruit of a wild orange he found growing at the foot of the hills. It is called “moccaly” by the natives. The fruit is rather tasteless, but the crushed pips heat the mouth like cayenne pepper. The geographer persisted in eating them conscientiously for the sake of science, until his palate was on fire, and he could no longer answer the questions the Major overwhelmed him with, about the peculiarities of the Australian wilderness.

Nothing of any importance happened he next day, December 26th. They came to the source of Norton Creek, and a little later, to the half-dried Mackenzie River. The weather kept fine, and the heat quite bearable. The wind was from the south, and refreshed the atmosphere as a north wind in the northern hemisphere, which Paganel pointed out to his friend Robert Grant.

“A happy circumstance,” he added, “because the heat is greater on the average in the southern hemisphere than in the northern.”

“Why?” asked the boy.

“Why, Robert?” answered Paganel. “Have you never heard that the earth is closer to the sun during the winter?”

“Yes, Monsieur Paganel.”

“And that the cold of winter is due to the obliquity of the solar rays?”

“Certainly.”

“Well, my boy, that’s why it’s warmer in the southern hemisphere.”

“I don’t understand,” said Robert, opening his eyes wide.

“Think, Robert,” replied Paganel, “when it is winter in Europe, what is the season here in Australia, at the antipodes?”

“Summer,” said Robert.

“Well, and since it is precisely at this time that the earth is nearest the sun — do you understand?”

“I understand—”

“That the summer in the southern regions is warmer than summer of the boreal regions, because of this proximity.”

“Indeed, Monsieur Paganel.”

“So when we say that the sun is nearer the earth ‘in winter,’ it is only true for us who inhabit the boreal part of the globe.”

“That is something I hadn’t thought of,” said Robert.

“And now, go, my boy. And don’t forget it.”

Robert took this little lesson in cosmography with a good grace, and learned, in conclusion, that the mean temperature of the province of Victoria was 74° Fahrenheit.4

In the evening the troop camped about five miles beyond Lake Lonsdale, between Mount Drummond, which rose to the north, and Mount Dryden, whose mediocre summit dotted the southern horizon.

The following day, at eleven o’clock, the wagon reached the banks of the Wimmera River, on the 143rd meridian.

The river, half a mile wide, wound its limpid course between tall rows of gum and acacia trees. Magnificent specimens of the Myrtaceae, the Metrosideros Speciosa, among others, fifteen feet high, with long, drooping branches adorned with red flowers. Thousands of birds — orioles, finches, and gold winged pigeons, not to mention the parrots — fluttered about in the green branches. Below, on the surface of the water, were a couple of shy and unapproachable black swans. This rara avis of the Australian rivers soon disappeared among the meanders of the Wimmera, which capriciously watered the attractive countryside.

The wagon stopped on a grassy bank, the long fringes of which dipped into the rapid current. There was neither raft nor bridge, but it was necessary to cross. Ayrton looked about for a suitable ford. About a quarter of a mile upstream the water seemed shallower, and it was here that he resolved to reach the other bank. Various soundings showed a depth of only three feet, which the wagon should safely negotiate.

“Is there any other way to cross the river?” Glenarvan asked the quartermaster.

“No, My Lord,” said Ayrton, “but the passage does not seem dangerous. We shall manage it.”

“Should Lady Glenarvan and Miss Grant get out of the wagon?”

“Not at all. My oxen are surefooted, and I will keep them on track.”

“Very well, Ayrton,” said Glenarvan. “I trust you.”

The horsemen surrounded the heavy vehicle, and resolutely entered the river. Normally, when wagons have to ford rivers, they have empty casks slung all round them, to keep them floating on the water; but they had no such swimming belt with them on this occasion, and they could only depend on the sagacity of the animals and the prudence of Ayrton, who directed the team. The Major and the two sailors were some feet in front. Glenarvan and John Mangles went at the sides of the wagon, ready to lend any assistance the ladies might require, and Paganel and Robert brought up the rear.

All went well until they reached the middle of the Wimmera, but then the channel deepened, and the water rose above the axles. The oxen were in danger of losing their footing, and dragging the oscillating vehicle with them. Ayrton devoted himself courageously. He jumped into the water, and hanging on by the horns of the oxen, succeeded in dragging them back onto the right path.

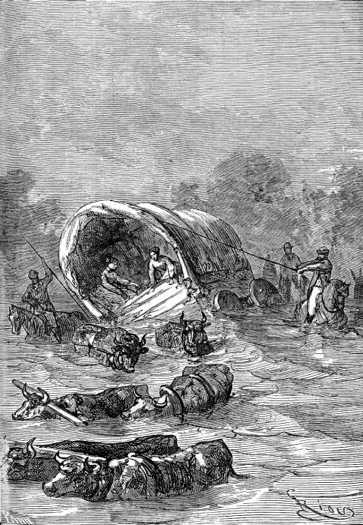

The wagon leaned precariously

The wagon gave a jolt that it was impossible to prevent; a crack was heard, and the wagon began to lean precariously. The water rose to the ladies’ feet; the whole concern began to drift, despite John Mangles and Lord Glenarvan clinging to the sides. It was an anxious moment.

Fortunately a vigorous effort brought the wagon closer the opposite shore, and the bank began to slope upward, so that horses and oxen were able to regain their footing, and soon the whole party found themselves safe on the other side, wet, but satisfied.

The front of the wagon, however, was broken by the jolt, and Glenarvan’s horse had lost a shoe.

This was an accident that needed to be promptly repaired. They looked at each other, hardly knowing what to do, until Ayrton proposed he should go to Black Point Station, twenty miles further north, and bring back a blacksmith.

“Yes, go, my brave Ayrton,” said Glenarvan. “How long will it take you to get there and back?”

“Perhaps fifteen hours,” said Ayrton, “but not longer.”

“Start at once, and we will camp here, on the banks of the Wimmera, until you return.”

A few minutes later the quartermaster, riding Wilson’s horse, disappeared behind a thick curtain of mimosas.

1. Plains watered by numerous springs.

2. Verne had 141° 30′ here, which would put them west of White Lake — DAS

3. 50,000 francs = $10,000 = £2,000 — DAS

4. 23.3° Centigrade — DAS